Asset Freeze Litigation 7-11-06

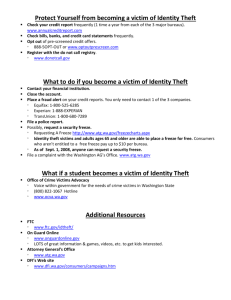

advertisement