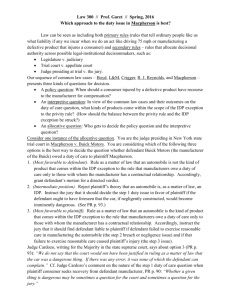

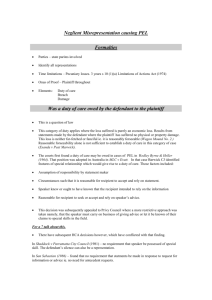

Table Of Edited Tort Cases

advertisement