1. understanding the market system: supply and demand

advertisement

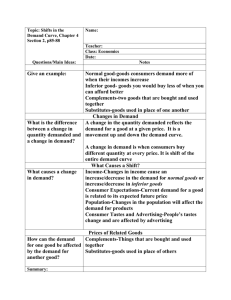

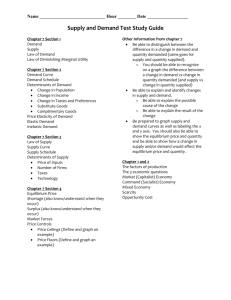

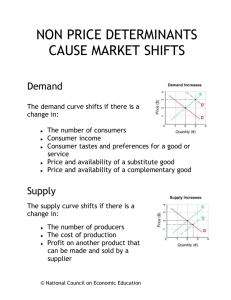

1. UNDERSTANDING THE MARKET SYSTEM: SUPPLY AND DEMAND The concept of demand and supply can be used to understand the nature of markets and how prices and output are determined and specific economic issues. Therefore, it is necessary to have a good understanding of the demand and supply principles. Markets defined A market is an institution or mechanism that brings together the buyers ("demanders") and the sellers ("suppliers") of particular goods and services. Markets assume a wide variety of forms. Common forms of agriculture, livestock and forest product markets include: the various vegetable, fruit and staple food bazaars where people buy raw food and take it to their homes for preparation; raw meat stalls and shops; the farmer's roadside stand; the door-to-door seller; the firewood merchant; the furniture seller; the farm produce and timber auctions. All situations that link potential buyers and sellers constitute markets. We shall concentrate on product markets, but keep in mind that many of the principles discussed have specific applications to resource markets. Demand In economics the term demand specifically refers to a schedule of combinations of the various amounts or quantities of a product that consumers are willing and able to purchase at a given price. This demand function is defined during a particular time by holding all other things and allowing only the quantity and the price to vary. The terms "willing and able" indicates that we are referring only to effective demand; we say "willing and able" because willingness alone is not effective in the market. For example, a family may need more protein food such as meat and cheese, than they are not able to purchase because of low income. Thus their effective demand remains low, while their real needs may be very high. Table 3.1 is a hypothetical demand schedule for an individual buying rice. Note that in order to be meaningful the quantities demanded must relate to a specific time period, in this case a week. Also, note that the demand schedule, in and of itself, does not tell which of the five possible prices actually exists in the market; this depends on both demand and supply. The demand schedule is simply a statement of a buyer's intentions. The actual determination of market price is explained in the Section on Market Equilibrium below. Table 3.1 An Individual Buyer's Demand for Rice (Hypothetical Data) Price of 1 kg of rice Nu 10 8 6 4 2 Quantity demanded per week Kg 1.0 2.0 3.5 5.5 8.0 1 The Law of Demand The law of demands states that all other things being equal, as price falls the corresponding quantity that is demanded rises, and vice versa. This law is based on the following foundations: i. Common sense and the simple observation that people buy more of a given product at a low price than they do at a high price. ii. The law of diminishing marginal utility: since successive units of a good yield less and less satisfaction, consumers will only buy additional units if the price is reduced. iii. The fact that if price is reduced, all other things being constant, the consumer effectively has more purchasing power, and can buy more of the good in question as well as other goods. Demand Curve The inverse relationship between product price and the quantity demanded can be presented on a simple two dimensional graph, measuring quantity demanded on the horizontal axis and the price on the vertical axis. The resulting curve is called the demand curve. (See Figure 3.1, depicting the graph from the numbers in Table 3.1.) The demand curve (D1D1 in Figure 3.1) slopes downward and to the right, because as the price falls from OP to OP1 demand increases to OM2 from OM0, while on the other hand when price increase to OP2 from OP, the quantity demanded decreases to OM1 fro OM. Figure 3.1 The Demand Curve for Rice Y Price O Qty demanded X Other Factors That Affect Demand Besides price, the demand for any good is affected by a number of other factors. When these non-price determinants of demand change, the location of the demand curve will shift to a new position to the left or to the right of D1D1, depending on the change in the 2 individual factor. For this reason, the non-price determinants of demand are called "demand shifters". Let us now have a look at each of these factors in turn. Tastes and Preferences Every person has his/her own tastes and preferences, and these influence whether they consume a good at all or whether they will consume more or less of good. Tastes and preferences are influenced by age, sex, religion, socio-cultural background, and so forth. A favourable change in consumer taste and preference for the good will mean that more of the good is desired at each price. The demand curve will thus shift to the right; see D”D” (Figure 3.2). An unfavourable change in consumer taste and preference will mean that less of the good is desired at each price. The demand curve will thus shift to the left, to; see D’D’ (Figure 3.2). Number of Buyers Clearly, an increase in the number of buyers, which may be brought about by improved transportation and access or population growth will increase the amount demanded of a commodity at any given price. Fewer consumers will result in a decline in demand. Income The effect of a change in income on demand is slightly more complex. For most goods, a rise in income will cause an increase in demand, and thus a shift of the demand curve to the right. Conversely a decrease in income would lead to a decline in the demand for most goods. Commodities whose demand varies directly with income are called superior or normal goods. Although most goods are normal goods, there are some exceptions. For example, as incomes increase beyond some point, the amount of certain starchy foods (like kharang, and cassava) may decline at each price, because the higher income allows consumers to buy more protein-rich foods such as dairy products and meat. Similarly, as income rises, the amount of domestic firewood consumed at any price may decline as people switch to electric and gas cookers and heaters. Goods whose demand varies inversely with a change in money income are called inferior goods. The term 'inferior' is used here only an economic sense, and is not meant to convey any judgments regarding the nutritive, taste, cultural, or any other values of such goods. Prices of Other Related Commodities. The prices of other commodities in the market will affect how much of a given commodity will be bought. Whether the change in the price of a related good will increase or decrease the demand for a given product will depend on whether the related good is a substitute for or a complement to the good in question. Substitute Goods. These are two products that have the same use, or can fulfil the same need. Groundnut oil and mustard are examples of two such goods. When the price of groundnut oil, consumers will purchase a smaller amount of it, and increase their demand 3 for mustard oil. To generalise: when two products are substitutes, the price of one good and the demand for the other are directly related. Complementary Goods. These are products that are used together, or are "jointly demanded". To some extent, ema (Bhutanese chillis) and datshi (Bhutanese cheese) may be an example of complementary goods. When the price of ema goes up, less of it is expected to be consumed. As a result, less datshi is is expected to be consumed too. To generalise: when two goods are complements, the price of one good and the demand for the other are inversely related. Independent Goods. Many pairs of goods are of course not related. These are referred to as independent goods. For such pairs of goods, for example, datshi and ink, the price of one would have little or no impact on the other. Expectations. Consumer's expectations about such things as future prices of products, product availability, and their own future incomes can shift the demand curve. For example, consumer expectation that the road between Phuntsholing and Thimphu will be closed during the monsoon may induce them to buy now in order to "beat" anticipated shortages and higher price. Change in Demand Versus Change in the Quantity Demanded A change in demand refers to a shift in the entire demand curve. This can be depicted in two ways: (Figure 3.2) Entire demand curve shifts to the right: this is an increase in demand; i.e. from DD to D2D2 and the demand in the market increases from OM to OM2 at the same OP price due to a positive change in other factors. While on the other hand the entire demand curve shifts to the left: this is a decrease in demand. i.e. from DD to D1D1 and the demand in the market decreases from OM to OM1 at the same OP price due to a negative change in other factors. Figure 3.2 Shift in the Demand Curve Y D D” O Qty. demanded X 4 A change in demand is caused by a change in one or more of the determinants of demand, other than own-price. Table 3.2 summarises the general effects of changes each of these factors on the position of the demand curve. In contrast a change in the quantity demanded designates the movement from one point on the demand curve to another point (Fig. 3.3). The cause of a change in the quantity demanded is a change in the price of the concerned product. The increase in price from OP to OP2 the quantity demanded decreases from OM to OM1 and when price decreases from OP to OP1, the quantity demanded increases to OM2 all due to change in the price. Figure 3.3 Change in quantity demanded Y D P Price D O Qty. Dd. X Table 3.2 Determinants of Demand: Factors that Shift the Demand Curve EXAMPLE FACTOR AFFECTING DEMAND GENERAL NATURE OF CHANGE 1. Consumer Tastes & Preference Favourable change in consumer tastes shifts demand curve to the right. Unfavourable change in consumer tastes shifts demand curve to the left. Kuensel publishes a medical study that shows chillis to be harmful to the stomach and thus to general health. If a significant number of Bhutanese were to accept the results of the study, this would lead to a decline in their taste and preference for chillis. The demand curve for chillis would then shift to the left. 2. Number of Buyers An increase in the number of buyers shifts the demand curve to n An agreement between the Bhutanese and Bangladeshi 5 the right. A decrease in the number of buyers shifts the demand curve to the left. Governments removes restrictions in the sale of Bhutanese agriculture and forest products in Bangladesh. This greatly expands the market for Bhutanese products and causes their demand curves to shift to the right. 3. Change in income An increase in income shifts the demand curve of normal goods to the right. That of inferior goods shifts to the left. A decrease in income shifts the demand curve of normal to the left. That of inferior goods shifts to the right. n The Government increases all public sector salaries by 15%. There will be an increase in the demand for normal goods like rice, meat and milk. There will be an decrease in the demand for inferior goods like kharang, re-soled tires and used clothing. 4. Changes in the price of related goods. An increase in the price of a substitute good causes the demand curve of the original good to shift to the right, and vise versa. An increase in the price of a complementary good causes the demand curve of the original good to shift to the left, and vise versa. An increase in the price of corrugated iron sheet causes the demand for roofing shingles to increase. An increase in the price of erma causes the demand for datshi to decrease. 5. Expectations Favourable expectations cause the demand curve to shift to the right, while unfavourable expectations cause it to shift to the left. Heavy monsoon rains cause the expectation of shortages of essential commodities in Thimphu, and therefore increases in their prices. The current demand for goods like rice thus increases. Supply In economics, the term supply specifically refers to a schedule of combinations of the various amounts a product that a producer is willing and able to produce and make available to buyers at each specific price. This is defined for a particular time, while holding all other things constant. Thus the supply schedule shows a series of alternative possible combinations such as those shown in Table 3.3. 6 Table 3.3 Individual Producer and Total Market Supply of Rice (Hypothetical) (1) (2) (3) (4) Price of 1 kg. Quantity supplied per week by Number of sellers Total market quantity supplied per of rice one producer week (2x3) Nu. 10 Kg. 120 200 Kg. 24,000 8 100 200 20,000 6 70 200 14,000 4 40 200 8,000 2 10 200 2,000 Note: Total supply at the market level (Column 4) is just the aggregation of all individual supply (Column 3). For simplicity, this case has 200 producers selling the same amount each at every price. The Law of Supply As Table 3.3 shows, there is a positive or direct relationship between price and the quantity supplied. This particular relationship is called the law of supply: as price increases the quantity supplied increases; and as price decreases, the quantity supplied decreases. As in the case of demand, this is largely a common sense matter. Price, you will recall is a deterrent to the consumer, the higher the price the less is consumed. On the other hand, to the supplier, price represents revenue per unit. It is, therefore, an inducement or incentive to produce and sell in the market. The higher the price, the higher is the incentive. The Supply Curve As in the case of demand it is convenient to graphically present the concept of supply. The graphing procedure is the same as that outline in Annex 1.B. The market supply data from Table 3.3 is graphed in Figure 3.4. The graph shows that quantity supplied is directly related to price. When the price increases from OP to OP2 the quantity supplied increases to OM2 while on the other hand when the price decreases to OP1 from OP the quantity supplied also decreases to OM1. Figure 3.4 Market Supply Curve for Rice S Y Price O Qty. supplied X 7 Other Factors That Affect Supply As with the demand curve, the position of the supply curve is given, "other things being equal". That is, the supply curve is drawn on the supposition that certain other non-price factors that determine the amount supplied are given and do not change. We shall now look into each of these determinants of supply in turn. Resource Prices or Prices of Factors of Production A business's supply is closely linked to the cost of the resource that it employs in production. A decrease in the price of resources will lower the cost of production and increase supply, that is, shift the supply curve to the right. Conversely, an increase in the price of resources will increase the cost of production, and shift the supply curve to the left. Technology. A technological innovation involves the discovery and adoption of new knowledge that allows us to produce a unit of output more efficiently, that is, with fewer resources. Such an innovation will lower the cost of production and shift the supply curve to the right. Taxes and Subsidies. Businesses treat most taxes as costs. Therefore, an increase in taxes on resources or produce will increase costs of production and reduce supply. Conversely, subsidies are treated as "reverse taxes". If Government subsidises the production of some good, the effect is to lower the cost of production and to increase supply. Prices of Other Goods Substitutes in production. These are goods that are competitive in production. An increase, say, in the price of tomatoes would cause the farmer to divert resources away from cabbage and into tomatoes. This would cause the supply of cabbage to decline. Complements in production. These are goods whose production goes hand in hand. An increase in the supply of one automatically increases the supply of the other. For example, an increase in the supply of mustard oil will automatically lead to an increase in the supply of mustard cake. Expectations. Expectations concerning the future price of a product may also affect the producer's current willingness to supply that product. However, it is difficult to generalise about how expectation will affect the present market supply curve. If farmers anticipate a higher price of rice in the future, they may withhold some of the current harvest from the market, and try to sell it when the price rises. Number of Sellers. In general, the greater the number of sellers in the market, the greater will be the market supply. Conversely, the smaller the number of sellers, the smaller is the market supply. For example, as the number of apple producers in Bhutan has increased, the supply of apples has also increased, i.e. the supply curve of apples has shifted to the right. The Aims of the Business Owner. Production is not always undertaken in order to obtain maximum profits. Certain outputs from a farm or any other business may be produced for prestige, psychological, or spiritual-religious satisfaction. The advantages of production may 8 be non-monetary (or non-pecuniary). If these aims change, production and, therefore supply, will change accordingly. Change in Supply Versus Change in Quantity Supplied The distinction between a "change in supply" and a "change in quantity supplied" parallels that between a change in demand and a change in quantity demanded. A change in supply involves a shift of the entire supply curve: an increase in supply shifts the entire supply curve to the right (S’S’); a decrease in demand shifts the entire supply curve to the left (S”S”) (Figure 3.5). A change in supply is due to change in one or more of the non-price determinants of supply. While on the other hand a change in the quantity supplied refers to a movement along the supply curve due to a change in the price. (Figure 3.5.) The quantity supplied increases with increase in price and decreases with decrease in price. In the Figure 3.5 when the price increases to OP2 from OP and the quantity supplied increases to OM2, while with the decrease in price to OP1 from OP, the quantity supplied also decreases to OM1 from OM. Figure 3.5 Change in quantity supplied Y S Price O Qty. supp. X Due to a change in other factors the entire supply curve in the market shifts either towards right or left (Figure 3.6). A positive change from a factor other than price will shift the entire supply curve towards right i.e. from SS to S”S” and the quantity supplied increases to OM@ from OM, while on the other hand the supply a negative impact will shift the entire supply curve towards left from SS to S’S” and the quantity supplied also decreases to OM1 from OM at the same market price. 9 Figure 3.6 Shift in the Supply Curve S’ Y S S” Price O Qty supplied X Relationship between supply and demand: market equilibrium We may now bring the two concepts of supply and demand together to see how the interaction of the buying and selling decisions will determine the market price of a product, and the quantity that is actually bought and sold in the market. The economic principles governing the market price of any product in a free market is illustrated in Table 3.4. Column 1 shows a common set of prices. Columns 2 and 3, respectively, reproduce the market supply schedule and the market demand schedule. Now, the question to be faced is this: Of the five possible prices at which rice might be sold, which one will actually prevail as the market price? Table 3.4 Supply and Demand Schedule for Rice (1) Price of 1 kg.of rice Nu. 10 8 6 4 2 (2) Total quantity supplied per week (3) Total quantity demanded per week (4) Excess supply per week (3-2) Kg. 24,000 20,000 14,000 8,000 2,000 Kg. 4,000 8,000 14,000 22,000 32,000 Kg. 20,000 ¯ 12,000 ¯ 0 ®¬ -14,000 -30,000 - Let us find the answer through trial and error. Could Nu. 10 be the prevailing market price for rice? The answer is no: at Nu. 10 producers are willing to supply 24,000 kg of rice; but buyers are willing to take only 4,000 kg. The result is a 20,000-kg surplus or excess supply of rice in the market (Column 4). The very large surplus of rice would prompt sellers to accept lower prices from buyers in order to get rid of this surplus. Thus whenever supply exceeds demand it leads to a downward pressure on price. 10 Supposing the price goes down to Nu. 8? At this price, there is still an excess supply of 12,000 kg. The downward pressure on price continues!! Now suppose the price goes further down to Nu. 6? At this price there is no surplus. In fact at this price, supply equals demand. This is the market equilibrium price with 14,000 kg of rice being sold, and 14,000 kg of rice being bought. But are we sure that this is the equilibrium price? To answer this question, let us see what happens when the price is allowed to fall still further to Nu. 4. At Nu. 4, we find that demand exceeds supply: producers are willing to sell only 8,000 kg of rice, while consumers are willing to buy 22,000 kg. Decreasing the price further to Nu. 2, would make the excess demand even greater: supplier will reduce the amount they are willing to sell to only 2,000 kg, while consumers will are willing to buy 32,000 kg. Then only way to achieve equilibrium again would be increase prices up to Nu. 6. In fact we can generally say that whenever demand exceeds supply, there is an upward pressure on price. A graphic analysis of supply and demand should yield the same conclusions. Figure 3.57 indicates that any price above the equilibrium price of Nu.6 will lead to a excess supply. This surplus will cause competitive bidding down of the price. Equilibrium will be attained when the price reaches Nu. 6. That is where the demand curve intersects the supply curve. Any attempt to sell or buy at a price lower than Nu.6 will lead to a shortage of supply over demand (or excess of demand over supply). This will cause competitive bidding up of the price, until the equilibrium is established again at Nu. 6. Figure 3.5 The Equilibrium Price and Quantity for Rice as Determined by Market Supply and Demand Y D S 11 O Qty. Suppd. & Dd. X 12