VERMONT TRIAL COURT CRIMINAL JURY INSTRUCTION

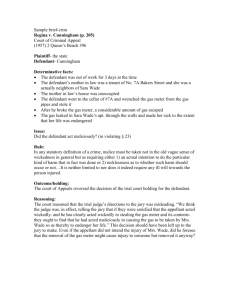

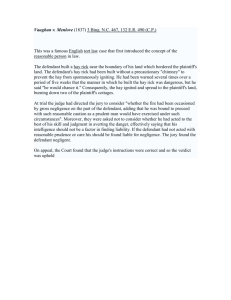

advertisement