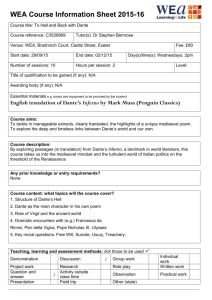

Brief Notes on The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri

advertisement

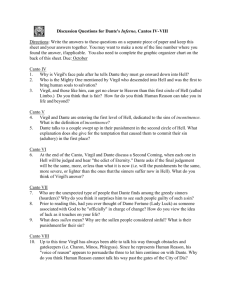

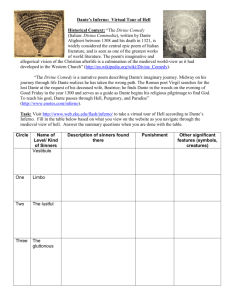

Brief Notes on The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri http://danteworlds.laits.utexas.edu/ and http://www.divinecomedy.org/divine_comedy.html The Life of Dante Alighieri: Dante was born in 1265 in Florence and died in 1321 in Ravenna. During his lifetime, there was much political turmoil in Florence. The papacy had gained and lost power, and was exiled in 1309 to Avignon. The popes were agonizingly corrupt. This returned imperial power to the city-states of Italy, but Florence was caught in a bitter civil struggle between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. The Guelphs were basically for rule by the Papacy, whereas the Ghibellines were imperialists. Later, the Guelphs themselves split into two factions. The White Guelphs, one of the factions, was for a blend of religious and secular rule. This was the party that Dane aligned himself with. 1302: Dante, very involved in politics, is exiled. La Divina Comedia, begun in 1300, will incorporate this event before it is completed. During his life, he had fallen in love (at age 9) with Beatrice Portinari, who died in 1290, at the age of 25, Dante was also 25. The poem is dedicated to her. She is his guide, and provides the allegorical figure for divine love, which in the poem, leads Dante to divinity from despair. The medieval thought of pure, blinding beauty and divine love as a kind of purging force to lead one out of darkness and weight of worldly traumas into the divine is of course evident in this poem, but Dante arrives at divinity though human reason, represented by Virgil. By using our own powers, humans can touch the powers of God: charity, wisdom, and power that can provide the salvation of humans – on earth. Dante’s ideal love does have a human analogy, without which we could not begin to imagine the divine. The best of human love is transfiguring and itself leads to a kind of transcendence of the body, of toil, of despair. This love is not to be maligned by human passion; it should always bear ills with grace, and to quote Shakespeare, be the “ever-fixed mark / That looks on tempests and is never shaken.” Of course, of all the wrong paths to go down, the one of false love is perhaps the easiest way to falter. The Inferno, at its best, tracks all the ways we deceive ourselves, so that Hell is a very real place, here on earth. In fact, all the sinners in Dante’s Hell are there unrepentant, believing that somehow they were justified in what they did—sometimes Dante the tourist, sympathizes with them, but Virgil (Reason) leads him on the true path, and makes him realize the folly of their ways. The Inferno characters are all victims of tragedy in its purest sense: they pursue knowledge without wisdom. (Divine guidance) They all thought they were doing what they needed to do, or what they couldn’t help but doing: Tragic heroes like Romeo, Brutus, Othello, and Oedipus always try to justify sin. Had Machiavelli been born, he surely would find his own comfortable Malebolge in which to reside in the deepest and coldest part of Dante’s inferno. Dante traverses Hell, a pit with no escape – circles – guided by love and reason and the power of God (fate). He journeys through Purgatory and Heaven—to what end? Virgil explains the intent of his journey for him in Canto I (101) and he hears the same lesson from Beatrice, at the end of Purgatorio. In Paradiso, Mary allows him to experience sanctifying grace (without first dying) and to return home. He is a mere mortal human, but with humility, faith, and human thought, he can know the cosmos, can know divinity and can discover redemption for the corrupt. If humans caused the downfall of the Church and the State, only humans could redeem it. With its expression of the power of human endeavor to correct as well as corrupt, Dante’s poem blasts open a big door in philosophy and literature. It is the portal to the Renaissance itself. Dante wanted to return from exile to help redeem Florence, but this wasn’t to be. The Divine Comedy contains a total of 100 cantos, all knit together in terza rima. There is a 34th canto for The Inferno (34). To contrive the landscape of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, Dante references Greco-Roman religion, St. Augustine’s City of God and the Summa Theologiae of St. Thomas Aquinas. Translations made by scholars in the more open, Islamic Spain during the early Middle Ages (800-1300) certainly provided inspiration. Due to this golden age, Dante had access to both the Qur’an and Hadith stories of Mohammed’s night voyage to Heaven, taking place at the site of the Dome of the Rock (the Temple of Solomon) in Jerusalem, and to the influences of philosophers such as the Jewish physician Maimomides, and the Muslim writer Averroes—both of whom argued the necessity of intellect in faith. NOTE: The heavenly joy that Dante seeks is within this world, not in Heaven. Quite literally in the text, he returns to Earth to experience the life-peace that he seeks. Hell and Heaven, and Purgatory are places that occupy our psychological reality in the here and now. Without this real connection to the here and now of our lives, the concepts themselves would never be so captivating. The Landscape of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven See Maps. Hell is a cone descending. The circles spiral down to the left in Hell and spiral up to the right in Purgatory. While there are nothing but steep drops and gullies in Hell, Purgatory has an occasional ladder. Heaven is made of spheres of aether, and one floats effortlessly from place to place, unhindered by earthly gravity. This is the only place Dante doubts his own corporality. Dante, at thirty-five years of age, in the year 1300, is chased away from his ascent up the Mount of Joy, into a dark wood of despair, or error (worldliness) by three beasts of sin: A she-wolf, a lion, and a leopard, representing incontinence, violence, and fraud. Only by recognition of sin, renunciation of sin and acceptance of Divine Love, will he be able to save himself. Cantos 1-3 Cantos 3-9 Cantos 10-17 Cantos 18-30 Cantos 31-34 Dante in the Dark Wood Upper Hell: Sins of the She Wolf/Incontinence Lower Hell: Sins of the Lion /Violence The City of Dis and The Great Barrier Sins of the Leopard / Simple Fraud: The 10 Malabolgia Sins of the Leopard / Fraud Complex: Cocytus, The Well Circles 1-5 Circles 6 and 7 Circle 8 Circle 9 Hell is for those who take the initiative to sin. In hell, the sinners get—not so much what they deserve, but what they want. Their punishment is a transmogrification of their sin. They are still pursuing the thing they did, and they still don’t get it, even when it causes them grave and endless suffering. In Hell, the circles descend, weighing down the sinners; the pursuit of earthly goals weighs down the body, and traps the soul, and excessive pride will not allow light in. Guilt builds thick walls, and the sinners continue to flee truth. The trap narrows; they are caught in their own justifications. To climb up is extremely difficult. Gravity weighs heavily on Dante and Virgil. Even in Purgatory, it is hard work to gain salvation, and natural gravity is the weight that souls there struggle against, as in life they struggled against the tug of worldliness. Eventually, the souls there will unburden themselves enough to be purged, and those souls will transcend to Heaven without effort. This is how humility feels, while guilt feels weighted. In Hell, the souls are truly lost; they don’t see that they have the power to end their own suffering. The descent from the dark wood has been interpreted as a descent into oneself, to discover the chaos within and purge it. Dante’s journey begins on Good Friday. By the morning of Holy Saturday, he enters Purgatory, and finds himself in Paradise on the morning of Easter Sunday. Although he cannot see the sky, Virgil is counting hours by the signs of the zodiac as they travel, and hurrying Dante along as a good tour guide would, keeping to schedule. As they travel through the landscape of Hell, Dante notes how similar it is to Earth. There are rivers and valleys and sand, cities, trees, swamps, wind—but there are no references to the sun. The lost souls are recognizable shades, who suffer bodily torment, although they themselves are non-corporal entities. They have the odd capacity to see the future, and know all about their own past, but don’t know the present as it exists on Earth. This could be considered a metaphor for their lack of moral probity, for in life they were constantly considering what had happened to them and what would become of them, but not the state their soul was currently in. They are, metaphorically, incapable of “being in the moment” but rather are locked within a dark cell of self-deception, which makes their present inconceivable, as well as unbearable and inescapable; they, in fact live completely void of the present, with no hope of light, blinded, unable to comprehend their place in the universe, and with no exit possible from themselves. The Bus Tour of Hell: Readings *Read Canto III, the entranceway to Hell *Read Canto IV (Circle 1) about who resides in Limbo *Canto V (Circle 2: The Lustful) Paolo and Francesca (Her husband was a hunchback. Paolo is her brother-inlaw.) What good arguments does she make in justifying the illicit love they shared? How does Dante react to their story? Note in your travels how many encounters Dante had with creatures and landscape drawn from Greco-Roman mythology. Even the Heavenly spheres, named for the planets, are the names of Roman gods and goddesses. Purgatory, too, has rivers from Hades, Lethe, in particular, where souls bathe and forget their earthly lives. Canto VI (Circle 3) Read about Cerberus, tormenting the Gluttons. Canto VIII (Circle 5 Crossing the River Styx) Note that Dante tips the boat when he enters, and alerts all the souls of his state of being alive. This is homage to Virgil, who had the same thing happen with Aeneas. *Canto X (Circle 6) Dante encounters Farinata, (a member of the Uberti clan) who is in hell for being an Epicurean, but who actually saved the city of Florence from destruction. Read Dante’s encounter with him, and his explanation of the odd vision of the dead souls in Hell. How does he try to justify himself? Cantos XII-XIII: Circle 7 is divided into three rings of those who do violence against others, against themselves and against God. These are still, however, lesser sins than those committed willfully, in cold-blood. Dante and Virgil meet up with the Centaurs, one of whom offers to transport them as they cross Phlegethon, the boiling river of blood in which is immersed murderers. One of the Centaurs notices Dante’s corporality when he moves things that brush against him. *Canto XIII: The Wood of the Suicides. How is this punishment fitting? Why does Virgil ask the questions for Dante? *Canto XVII: How do the travelers get down to Circle 8, past the Great Barrier? How is this human scorpion, the Geryon, an apt symbol for the circle of the fraudulent? *Cantos XX-XXIII (Journey from the fifth malebolge in Circle 8, to the sixth) Burning pitch for the barrators. Read how Virgil saves Dante from pursuing demons, and they find their way through the circle of hypocrites. Note also that they are thinking with one mind: Virgil is in possession of Dante’s thoughts. Note the many epic similes, endemic of epic poetry. Note, also Michael the Scot, famous medieval translator of Arabic, (d. 1232) for Frederick II, in Canto XX. *Cantos XXIV-XXV (Sixth malebolge, the Hypocrites) How are they tormented? What did Vanno Fucci do? *Cantos XXVI-XXVII: See notes. *Canto XXXIII-XXXIV: Count Ugolino Circle 9: Who resides there and why? (Note Branca Doria’s soulless self still survives!) How do Dante and Virgil travel beyond Lucifer, and find their way? Ulysses Alfred, Lord Tennyson It little profits that an idle king, By this still hearth, among these barren crags, Match'd with an aged wife, I mete and dole Unequal laws unto a savage race, That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me. I cannot rest from travel: I will drink Life to the lees: all times I have enjoy'd Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those That loved me, and alone; on shore, and when Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades Vest the dim sea: I am become a name; For always roaming with a hungry heart Much have I seen and known; cities of men And manners, climates, councils, governments, Myself not least, but honour'd of them all; And drunk delight of battle with my peers; Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy. I am part of all that I have met; Yet all experience is an arch wherethro' Gleams that untravell'd world, whose margin fades For ever and for ever when I move. How dull it is to pause, to make an end, To rust unburnish'd, not to shine in use! As tho' to breath were life. Life piled on life Were all to little, and of one to me Little remains: but every hour is saved From that eternal silence, something more, A bringer of new things; and vile it were For some three suns to store and hoard myself, And this gray spirit yearning in desire To follow knowledge like a sinking star, Beyond the utmost bound of human thought. This is my son, mine own Telemachus, To whom I leave the sceptre and the isleWell-loved of me, discerning to fulfil This labour, by slow prudence to make mild A rugged people, and thro' soft degrees Subdue them to the useful and the good. Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere Of common duties, decent not to fail In offices of tenderness, and pay Meet adoration to my household gods, When I am gone. He works his work, I mine. There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail: There gloom the dark broad seas. My mariners, Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with meThat ever with a frolic welcome took The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed Free hearts, free foreheads- you and I are old; Old age had yet his honour and his toil; Death closes all: but something ere the end, Some work of noble note, may yet be done, Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods. The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks: The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends, 'Tis not too late to seek a newer world. Push off, and sitting well in order smite The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of all the western stars, until I die. It may be that the gulfs will wash us down: It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho' We are not now that strength which in the old days Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are; One equal-temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield (1842) Four Translations of Dante (Note too, John Sinclair’s prose translation!) Looking at Dante’s La Divina Comedia, let's compare the original with three different translations: John Ciardi, Dorothoy Sayers, and Robert Pinsky. This is the very famous "Entrance to Hell" passage at the beginning of Canto III. Dante Alighieri: Per me si va ne la città dolente. per me si va ne l'etterno dolore, per me si va tra la perduta gente. Giustizia mosse il mio alto fattore; fecemi la divina podestate, la somma sapienza e 'l primo amore. Dinanzi a me non fuor cose create se non etterne, e io etterna duro. Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch'intrate." Queste parole di colore oscuro vid'io scritte al sommo d'ura porta; per ch'io: "Maestro, il senso lor m'e duro." Ed elli a me, come persone accorta: “Qui si convien lasciare ogne sospetto; ogne viltà convien che qui sia morta. Noi siam venuti al loco ov’i’t’ho detto che tu vedrai le genti dolorose c’hanno perduto il ben de l’intelletto. a b a b c b c d c d e d e f e f g f Note the pattern of terza rima: The first and third lines rhyme. The middle line rhymes with the first and third lines of the next tercet (three lines of poetry). There is always a trio of rhyming words. The middle line of that tercet is a new rhyme that corresponds to the first and third lines of the next tercet. In Italian, where there are many words that rhyme, this evidently, poses a nice little challenge in finding words that suit meaning. However, in English, that’s no LITTLE challenge! Of the four translators, only Dorothy Sayers has chosen to sacrifice meaning and fluidity of language to achieve terza rima, and it shows in a rather clunky verse: (Diuturnal? Supernal? Eterne? Unsearchably? Hmmm....) Mark Musa recently did another translation for Penguin Classics, which is more contemporary and readable: Dorothy Sayers: Mark Musa: Through me the road to the city of desolation, Through me the road to sorrows diuturnal, Through me the road among the lost creation. Justice moved my great maker; God eternal Wrought me: The power, and the unsearchably High wisdom, and the primal love supernal. Nothing ere I was made was made to be Save things eterne, and I eterne abide; Lay down all hope, you that go in by me." These words, of sombre colour, I descried Writ on the lintel of a gateway; "Sir, This sentence is right hard for me," I cried. I am the way into the doleful city, I am the way into eternal grief, I am the way to a forsaken race. Justice it was that moved my great creator; Divine omnipotence created me, And highest wisdom joined with primal love. Before me nothing but eternal things Were made, and I shall last eternally. Abandon all hope, all you who enter. I saw these words spelled out in somber colors Inscribed along the ledge above a gate; “Master,” I said, “these words I see are cruel.” Here's Robert Pinsky's new translation, very fluid and poetic, but he will wander considerably from the text throughout the translation. He has chosen, as has also Allen Mandelbaum (your translation) and Seamus Heaney in his recent translation of Beowulf, to provide the poem in its original language, aside the translation. This way, you can see the original, and possibly forgive the poet for creating something new. Robert Pinsky: Through me you enter into the city of woes, Through me you enter into eternal pain, Through me you enter the population of loss. Justice moved my high maker, in power divine, Wisdom supreme, love primal. No things were Before me not eternal; eternal I remain. Abandon all hope, you who enter here." These words I saw inscribed in some dark color Over a portal. "Master," I said, "make clear Their meaning, which I find to hard to gather. John Ciardi pays homage to terza rima in rhyming at least the first and third lines of the tercets. He is also a bit more reliable than Pinsky in keeping to a line by line rendition of Dante's verse, but chooses a middle ground from Sayers in achieving meaning. It's another reason I like him, aside from his terrific notes. John Ciardi: I am the way into the city of woe, I am the way to a forsaken people. I am the way into eternal sorrow. Sacred Justice moved my architect. I was raised here by divine omnipotence, Primordial love and ultimate intellect. Only those elements time cannot wear Were made before me, and beyond time I stand. Abandon all hope, ye who enter here. These mysteries I read cut into stone above a gate. And turning, I said: "Master what is the meaning of this harsh inscription? Wow, huh? It's pretty staggering, which is why it's worth it to read poetry in the original. You can likely puzzle out many cognates, or get an dual language dictionary. It makes me think it must be discombobulating to translate poetry—or to write anything in terza rima? Take a shot at it! Prufrock and Ulysses: Allusion to Dante’s Inferno One of Virgil’s poems, the Fourth Ecologue, seems to predict the birth of Christ. He is seen as one endowed both with Divine Love and tremendous Human Reason, and, of course, extreme eloquence. For these reasons, and for his Italian birth, Dante’s guide in the Inferno is Virgil. Virgil, who represents Human Reason, cannot, however, guide him into Paradise: Only Divine Love can achieve that. In the political wars between GUELPHS AND GHIBELLINES (the pro-Papal and Imperial parties, respectively) Dante was originally a Guelph. The Guelphs later split into Black and White factions, Dante favored the Whites, who, suspicious of Pope BONIFACE VIII’s designs on Florence, gradually took on the political coloration of the Ghibellines, whose ideal was a unified, peaceful Italy under the temporal authority of the Holy Roman emperor. Circle Eight (Located in the Malebolge. Bolgia means abyss): The Evil Counselors See map. Notice how close this pit is to the very center of Hell. Dante was forced out of Florence from his position as Chief Magistrate into exile by those whom he considered evil counselors. These evil counselors steal and abuse the holy gift of persuasion, which was given to the disciples to spread the teachings of Jesus. The abuse of this particular virtue is why the sinners in this pit appear to be consumed by tongues of flame, alluding to the appearance of tongues of flame above the heads of the apostles at Pentecost, which signified the arrival of the Holy Spirit, and endowed the apostles with the ability to speak eloquently in many languages. (This is a contrast to the Tower of Babel story. Pentecost is 50 days after Easter, 10 days after the Ascension of Christ to Heaven until the Parousia.) Because the evil or false counselors abused this gift from God, they are stolen from sight and hidden in the great flames that are their own guilty consciences. (Since they sinned by the glibness of their tongues, in their punishment the flames that consume them resemble the tongues of flame from the Pentecost.) Among these sinners are, in Canto XXVI, Ulysses and Diomedes, who “tricked” the Trojans into accepting the horse… and Guido da Montefeltro, in Canto XXVII. (Three offenses committed by Ulysses and Diomedes: the wooden horse; luring Achilles into the war effort –he abandoned Deidamia and their son; and stealing the Palladium.) Ulysses, as portrayed by Dante: Naturally, as an Italian who closely associates himself with Virgil, considered by Dante to be the greatest poet ever, ever, Dante is no great fan of Odysseus, whose Latin name, is Ulysses. In the Aeneid, Ulysses is much maligned. He is portrayed as a treacherous thief, who steals a statue of Athena from the Palladium (the temple to her in Troy) and a perfidious schemer, who purposely puts his men in danger, betraying them for his own selfish ends. In the Odyssey, these traits are more or less considered heroic hamartia. He pays for his crimes, but the audience of the Odyssey, through the genius of Homer, is also beguiled – as is Athena herself – by his wit, strategy, and wily tactics. Dante, of course sees Ulysses as Virgil did. After all, he convinced Achilles to go and fight the war, and to kill Hector. Aeneas, a Trojan and the founder of Rome, leaves his ravaged city to travel on his own Odyssey to become the father of the Roman Empire, as Virgil heroically paints him in the Aeneid. Dante provides here a story that was probably lost from classical literature: what happens to Ulysses in the end. Read and learn. What is his sin? What happens to Homer’s depiction of Odysseus as a loyal husband, son, and father? Is it evident that he is not repentant? (Note: Dante creates much sympathy for many of the sinners in Hell – even the most despicable, for he brilliantly allows them to argue their innocence with the kind of false logic the readers could easily imagine themselves believing! Some of the most sympathetic characters in Hell are referred to as magnanimi.) What lesson does Dante himself, as a poet, learn in this malebolgia? What contemporary warning could Dante be giving to his contemporaries? (Note the reference to Circe. In his notes to the Inferno, John Ciardi writes that Circe was the sorceress who “changed Ulysses’ men to swine and kept him a prisoner, though with rather exceptional accommodations.”) But knowledge does not equal virtue. Those with the gift of tongues should use it wisely and to noble purposes. Read Tennyson’s Ulysses. What benefit does the poet gain from using Ulysses himself as speaker? In Book XI of The Odyssey, Tireseus foretells a peaceful death for Odysseus, but translations vary: Richard Lattimore says: “Death will come from the sea…” in an ebbing, peaceful way. Allen Mandelbaum says “not at sea,” and Robert Fagles translates the same passage as “far from the sea it comes.” Robert Fitzgerald talks of the death as “a seaborne death soft as this hand of mist.” Samuel Butler’s prose translation also speaks of a “death from the sea.” He does meet Achilles, in Book XI of The Odyssey, who famously tells him, “Odysseus, don’t embellish death for me. I’d rather be another’s hired hand, working for some poor man who owns no land…than to rule over all whom death has crushed.” (Homer. The Odyssey. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Bantam Books, 1990. Print.) This is another example of how Tennyson's subtle use of allusion shades the meaning of the poem. However, the point is made by Ulysses himself: Even tedious death in Elysium, even burning in Dante's malbolge -- is worth the final rush. By placing the words in Ulysses' mouth rather than in his own, Tennyson really leaves us the option of making our own choice as well. It might be that Old Man Tennyson himself would have agreed with Ulysses.... Although, perhaps wisely, wouldn't himself advise it to others! ;) All ancient sources seem to say that Odysseus will be old, wealthy, at peace, and surrounded by family. The sea seems to deliver the death, something like a plague or miasma, although he himself will not be far away on the ocean. Prior to death, he is instructed to go to a country where people are not seafarers, who will mistake his oar for a winnowing fan, and pay homage to Poseidon. But note his position in The Inferno, the source that Tennyson likely draws his reference. And then, of course the prologue to Star Trek: Space... the Final Frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Her ongoing mission: to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life forms and new civilizations, to boldly go where no one has gone before. Guido da Montefeltro T.S. Eliot, who said, “Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them, there is no third,” alludes to both Dante and Shakespeare in his famous poem, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. In the following decidedly direct and prosy translation, the opening quotation is spoken by Guido, in Hell: If I thought my answer were given to anyone who would ever return to the world, this flame would stand still without moving further. But since never from this abyss has anyone ever returned alive, if what I hear is true, without fear of infamy, I answer you. Actually, when you learn of him, Guido probably wants fame, but fears infamy. The speech is poignant for its dramatic irony. Dante, of course, will return – and he is no friend of Guido! He reacts to Dante’s cool silence with nervous passion. Guido’s passionate telling of his story, like so many of the other sinners in Hell, evokes sympathy. The readers, however, cannot absolve the sinners any more than can God, for their own lack of repentance and sense of responsibility. Recall that the sinners in Hell have the ability to see the past and the future, but as the present approaches, their ability to see it dims. The real sympathy comes from this: no matter how eloquent or intelligent, or mystified they are by what they don’t understand, the sinners are guilty. Calculation is no substitute for morality. Often tyrants claim that their “end” is peace, though their “means” is brutality. Note: About two centuries after Dante’s death, another Florentine, Machiavelli would write, Il principe. But if anything Dante’s Comedia is a lesson in humanism, a journey to meet its most noble and most repugnant representatives. Had he prescience, Dante the author, I’m sure, would have placed his paisan Niccolo, right there next to Guido. Had Dante, the voyager, known to look, I’m sure he would have seen him there. Guido was head of the Ghibelline faction in Romagna, and was reputed to be the most wise and cunning man in Italy. In his earlier life, he was a ruthless military man, opposed the Pope, as a Ghibelline, and later made peace with the Church and became a Franciscan monk. He was called by Pope Boniface VIII to help him settle a personal feud. (Boniface supposedly convinced the previous pope, Celestine V, to abdicate.) Boniface was a member of the Caetani family, long at odds with the Colonna family, who had a stronghold in Palestrina (Penestrino). The Colonnas were questioning the validity of his office, and Boniface wanted to crush them. He promised Guido absolution – and other rewards – no matter what the outcome of his “advice” would be. Guido told him to declare a false amnesty to the Colonnas to gain access to the castle at Palestrina, and then raze it to the ground, sparing no one, which Boniface did. The logic of forgiveness doesn’t hold: you cannot be absolved for a sin in advance, especially one for which you have pride in committing! (Aristotle’s principal of noncontradiction.) The Pope possesses two keys: absolution and discernment – Boniface misuses both. Guido blames him, but really! He claims he was innocent because he was obeying the Pope, but he doesn’t fool either St. Francis or the angels after his death. (Friar’s Tale) Both Ulysses and Guido sin in their old age. Instead of sailing restfully into port, making amends for past sins, they are moved by pride to sin again. Simple love and simple service is not satisfying, and they have little humility. In the end, Guido cannot figure out where he’s gone wrong, and seems to blame others for the fact he isn’t tremendously famous and revered – let alone damned. How is he a good spokesperson for Prufrock? J. Alfred Prufrock For J. Alfred Prufrock, Where has the pursuit of a sophisticated, but barren life brought him? Does he understand how his life has become so meaningless – or even that it is meaningless? The goal is not to avoid Hell, per se, but to avoid Hell on Earth, and is there a difference? Has he any humility? He has woken in darkness, and doesn’t know how he got there. Is he still in the nightmare, dissolute, dissatisfied, bitter, sad, and depressed? How to exit? He is seeking connection through idle pursuits, not even knowing what it is exactly he’s trying to achieve, and blaming others for the failure of the act to yield meaning. “How did I get here? Why me? Didn’t I do everything right?” wonders Guido. Well, who doesn’t bend rules to achieve something? Intellectualism has its dark side: the polished artists or critics of music and art, the condoned, civilized pursuers of market success, bohemian outsiders, and trend setters – all living in vapid worlds eloquently masked as intense and passionate modes of life. But one’s failure to give, to have real human life beyond the mask of it, will yield only darkness. Success of this nature is a miasma, a pestilent wind, beautiful and intoxicating and promising power, but not intensely real. (Human Reason cannot achieve Paradise – That can only be achieved through Divine Love. Do I mean Paradise, or Paradise on Earth? Does it matter?) How many vastly successful failures will join Prufrock in Hell? Or – is there a sign of hope for him? Does he know how to begin? Dante Alighieri called Dante, b. Florence, Italy, June 5, 1265, d. Sept. 14, 1321, wrote the poetic masterpiece La Divina Comedia, or The DIVINE COMEDY, which helped establish his native Tuscan dialect as the literary language of Italy. He is not only Italy’s preeminent poet but, along with Shakespeare, one of the towering figures of Western literature. This primacy is accorded him because of his profound understanding of medieval thought, his mastery of complex technical skills, and the dramatic range and originality of his imagination. Dante’s life spanned the troubled years of the late Middle Ages, in which the long struggle between pope and emperor for supremacy in Italy reached its most acute phase, and in which the concept of nationalism, exemplified by the growing power of the French monarchy, was displacing the medieval vision of a united Christendom. Deeply involved in the issues and events of his day, Dante reflected in his writings the aspirations and anxieties of his contemporaries, while projecting into them a universal and timeless dimension. Of a middle-class Florentine family with some pretensions to ancient nobility, Dante received a good education both in the classics and in scholastic Christian literature. At a very early age he began to write poetry, largely love lyrics (canzoni) in the style of Guido Guinizelli and Guido CAVALCANTI. According to Giovanni BOCCACCIO, Dante also studied painting and music. The most memorable events of his youth were his two encounters (1274 and 1283) with BEATRICE Portinari, to whom he remained spiritually devoted for the rest of his life—in a metaphysical transformation of the tradition of COURTLY LOVE popularized by the Provencal troubadours—despite his own marriage (c.1285) to Gemma Donati (which produced several children) and Beatrice’s to Simon de’Bardi. The progression of his love for her was embodied in the love poetry of his first book, La vita nuova (The New Life, c.1293), written a few years after Beatrice’s death in 1290. In the much later Divine Comedy, she assumes the role of the poet’s savior and guide and bears the allegorical significance of Faith or Theology. In the political wars between GUELPHS AND GHIBELLINES (the pro-Papal and Imperial parties, respectively), Dante was originally a Guelph and in 1289 fought with his fellow citizens against the Ghibellines at the Battle of Campaldino. When the Guelphs later split into Black and White factions, Dante favored the Whites, who, suspicious of Pope BONIFACE VIII’s designs on Florence, gradually took on the political coloration of the Ghibellines, whose ideal was a unified, peaceful Italy under the temporal authority of the Holy Roman emperor. At the turn of the century, Dante held high public office, having risen from city councilman to prior and occasional ambassador of Florence. This career ended in 1301 when the Black Guelphs and their French allies seized control of the city. In 1302 they confiscated Dante’s possessions and sentenced the poet to permanent banishment from Florence, and to the death penalty should he ever return. Thereafter Dante lived in various centers sympathetic to the Ghibelline cause, most notably at the courts of Can Grande della Scala in Verona and Guido da Polenta in Ravenna after the death (1313) of the Holy Roman emperor HENRY VII finally ended his hopes for an imperial victory. This long exile marked the beginning of a steady literary output. De vulgari eloquentia (On the Vulgar Speech, c.1304-06), in Latin, is a pioneering study of linguistics and style in which Dante argues for the use of the vernacular in serious works of literature and for combining a number of Italian dialects to create a new national language. De Monarchia (On Monarchy, c.1313), also in Latin, presents Dante’s case for a world order united by one ruler who would be supreme in secular affairs, while the church, no longer a rival for worldly power, would remain sovereign in spiritual matters. Dante also experimented further with style and content in individual poems and wrote Latin epistles and eclogues. Dante’s reputation rests on his last work, the Comedia, begun between 1307 and 1314 and finished only a short time before his death (1321). Composed in a three line-stanza form, called TERZA RIMA (Dante’s invention) and divided into three parts, the Comedy follows the poet’s journey from the “dark wood” in which he finds himself in middle age; through the nine circles of the damned in the Inferno and the mountainous wasteland of the Purgatorio, with the poet VERGIL as his guide; to his final comprehension of the divine plan of justice in the Paradiso, aided by his beloved Beatrice. An allegorical compendium of the medieval moral and scientific world view in its subtlest form, The Divine Comedy simultaneously reached out to the past and the future. Vergil’s poetic influence on the work constituted a tribute to Italy’s classical past, and the vigorous adoption of popular speech and the realization of a large cast of very human, often contemporary, characters helped free Italian literature from its ancient confines. With this work, Dante became Italy’s first national, and thus modern, poet, even as he gave voice to religious and political ideals that defied any temporal category. Thomas G. Bergin Bibliography: Auerbach, Erich, Dante, Poet of the Secular World, trans. by Ralph Manheim (1961; repr. 1988); Bergin, Thomas G., Dante (1965; repr. 1976), A Diversity of Dante (1969), and Perspectives on the Divine Comedy (1967); Brandeis, Irma, Ladder of Vision (1960); Caesar, Michael, Dante (1989); Chubb, T. C., Dante and His World (1966); Cosmo, Umberto, Handbook to Dante Studies, trans. by David Moore (1950); Croce, Benedetto, The Poetry of Dante (1922); Fergusson, F., Dante (1966); Foster, Kenelm, The Two Dantes and Other Studies (1978); Fowlie, Wallace, A Reading of Dante’s Inferno (1981); Freccero, John, ed., Dante (1965) and Dante, The Poetics of Conversion (1986); Gilbert, Allan H., Dante and His Comedy (1963); Gilson, Etienne, Dante the Philosopher, trans. by David Moore (1949); Grandgent, C., Companion to the Divine Comedy, ed. by Charles S. Singleton (1975); Hollander, Robert, Allegory in Dante’s Comedia (1969); Holmes, George, Dante (1980); Kirkpatrick, R., Dante: The Divine Comedy (1987); Mazzotta, Giuseppe, Dante, Poet of the Desert (1987); Musa, Mark, Advent at the Gates (1974); Singleton, Charles, S., Dante Studies I a Limbo in Roman Catholic theology, the border place between heaven and hell where dwell those souls who, though not condemned to punishment, are deprived of the joy of eternal existence with God in heaven. The word is of Teutonic origin, meaning “border,” or “anything joined on.” The concept of limbo probably developed in the European Middle Ages. Two distinct kinds of limbo have been supposed to exist: (1) the limbus patrum (“fathers' limbo”), which is the place where the Old Testament saints were thought to be confined until they were liberated by Christ in his “descent into hell”; and (2) the limbus infantum, or puerorum (“children's limbo”), which is the abode of those who have died without actual sin but whose original sin has not been washed away by Baptism. This “children's limbo” included not only dead unbaptized infants but also the mentally defective. The question of the destiny of infants dying unbaptized presented itself to Christian theologians at a relatively early period. Generally speaking, it may be said that the Greek Fathers of the Church inclined to a cheerful view and the Latin Fathers to a gloomy view. Indeed, some of the Greek Fathers expressed opinions that are almost indistinguishable from the Pelagian view that children dying unbaptized might be admitted to eternal life, though not to the Kingdom of God. St. Augustine recoiled from such Pelagian heresies and drew a sharp antithesis between the state of the saved and that of the damned. Later theologians followed Augustine in rejecting the notion of any final place intermediate between heaven and hell, but they otherwise were inclined to take the mildest possible view of the destiny of the irresponsible and unbaptized. The Roman Catholic church in the 13th and 15th centuries made several authoritative declarations on the subject of limbo, stating that the souls of those who die in original sin only (i.e., unbaptized infants) descend into hell but are given lighter punishments than those souls guilty of actual sin. The damnation of infants and also the comparative lightness of their punishment thus became articles of faith, but the details of the place such souls occupied in hell or the nature of their actual punishment remained undetermined. From the Council of Trent (1545–63) onward, there were considerable differences of opinion as to the extent of the infant souls' deprivation, with some theologians maintaining that the infants in limbo are affected with some degree of sadness because of a felt privation, and other theologians holding that the infants enjoy every kind of natural felicity, as regards their souls now and their bodies after the Resurrection. The concept of limbo has remained similarly undefined and problematical in modern Roman Catholic doctrine. Catechism: All unbaptised receive the grace of God. All who stove to do good in their lives have a chance for salvation. There is no mention of “limbo” anymore. I believe Vatican II did away with the word.