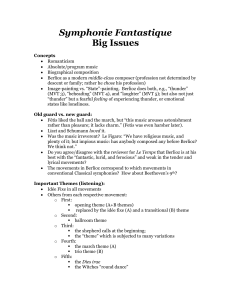

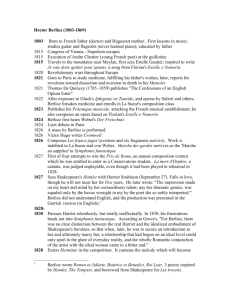

Saturday April 14, 2012, 8:00 pm Finney Chapel Concert No. 258

advertisement

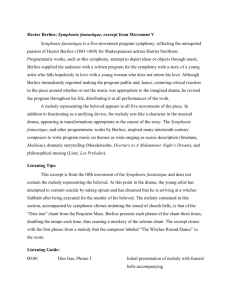

Oberlin Chamber Orchestra Saturday April 14, 2012, 8:00 pm Finney Chapel Concert No. 258 Raphael Jiménez, conductor Beomjae Kim, flute Love Scene from Romeo and Juliet, Op.17 Flute Concerto I. Allegro moderato II. Allegretto Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) Beomjae Kim, flute Intermission Ma mère l’oye, “Mother Goose” I. Prelude II. Dance of the Spinning-Wheel and Scene III. Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty IV. Conversations of Beauty and the Beast V. Tom Thumb VI. Little Homely, Empress of the Pagodas VII. The Fairy Garden Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) Please silence all electronic devices and refrain from the use of video cameras unless prior arrangements have been made with the conductor. The use of flash cameras is prohibited. Thank you. Biography Flutist Beomjae Kim has performed in orchestral and chamber music concerts in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Solo performances sponsored by UNICEF and Kumho Cultural Foundation have featured him at concert halls such as the Seoul Art Center Kumho Art Hall. In summer of 2011, he was invited to give solo recitals at the Alba Muisc Festival in Italy, and the International Dani Muzike Festival in Montenegro. Winter of 2011 saw him perform with world-renowned flutist Philippe Bernold and pianist Boris Kaljevic at Bali Classical Nights in Indonesia. He has also appeared in recital with percussionists Filippo Lattanzi and Marco Pacassoni. Upcoming engagements include recitals in Eastern Europe, and performances at Boston University’s College of Fine Arts. Kim has also performed in orchestras led by recognized conductors such as MyungWhun Chung, Raphael Jiménez, Joseph Mechavich, Tito Muñoz, Mark Russell Smith, and Ari Pelto. He has collaborated with artists such as Paul Boufil, Stéphane Réty, and Michel Debost in chamber music concerts. In 2007, Kim was awarded 4th prize in the Junior Division of the first Concours International de Flûte Maxence Larrieu. For the 13th Japan Flute Convention, he was invited to perform in Andràs Adorjàn’s master class. Kim is completing his bachelor’s degree at Oberlin where he studies with Alexa Still, Michel Debost, and Kathleen Chastain. Program Notes Love Scene from Romeo and Juliet: A Dramatic Symphony, Op. 17 (1839) by Hector Berlioz (La Côte-Saint-André, Isère, France, 1803 – Paris, 1869) The French Romantic generation received a vital impulse from the works of Shakespeare. Victor Hugo in literature, Delacroix in painting, and Berlioz in music were all inspired by the Bard, who, although long known in France, was re-discovered in the late 1820s through a new series of translations and, in particular, through the Paris performances of William Abbott’s Shakespeare company that opened at the Odéon theatre in September 1827. The French celebrated in Shakespeare the Romantic poet in whose works passion did not yield to reason as it often did in French classical drama; they marveled at the complex plots, at the fusion of comedy and tragedy, at the freedom from formal constraints. In Berlioz’s case, in any event, one could not entirely separate his enthusiasm for Shakespeare from his infatuation with the leading lady of Abbott’s company, Harriet Smithson, who played both Ophelia and Juliet at the Odéon. The actress, who at first didn’t want to have anything to do with Berlioz, became the composer’s idée fixe, inspiring his first masterpiece, the Symphonie fantastique. They were formally introduced only in December 1832, and less than a year later, they were married. The marriage, however, was not happy one, and the couple separated in October 1844. Shakespeare was central to Berlioz’s artistic world throughout the composer’s life. His Shakespearean fever began with a fantasy for chorus and orchestra on The Tempest (1830) and an overture to King Lear (1831). Thirty years later, Berlioz turned to Shakespeare again for his last major work, the opera Beatrice and Benedict (1860–62), writing his own libretto based on Much Ado About Nothing. Berlioz’s most monumental Shakespearean work is, without a doubt, the dramatic symphony Roméo et Juliette. After first seeing Harriet Smithson in the role of Juliet, Berlioz had reportedly exclaimed: “That woman shall be my wife, and on this play I shall write my grandest symphony.” In his memoirs, Berlioz denied having made this prophetic statement, yet others swore they had heard it. At any rate, there is evidence that he started thinking about a work based on Shakespeare’s play no later than 1829. By 1831, he knew he wanted to write a scherzo on Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech, and he talked of his plans to Mendelssohn during their first meeting in Italy. (According to one report, Berlioz was concerned that Mendelssohn might write a Queen Mab scherzo himself, before Berlioz himself had a chance to do so. Years later, Mendelssohn did write a Shakespearean scherzo for his incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream; the similarities between the two scherzos indicate that neither composer had forgotten the conversation they had had in the countryside outside Rome.) In the same year 1831, Berlioz wrote a scathing review of Bellini’s opera I Capuleti ed i Montecchi, in which he provided what seemed like a blueprint of his own approach to the subject. (He apparently didn’t know that Bellini’s opera was not based on Shakespeare but on some of the old Italian sources Shakespeare himself had used.) The score of Roméo et Juliette was finally written during seven months in 1839. It was an unexpected fortunate event that enabled Berlioz to devote himself fully to his work during this period. Years earlier, Niccolò Paganini had been interested in commissioning a viola concerto from Berlioz, which eventually became Harold in Italy. Berlioz’s and Paganini’s ideas about the planned work differed considerably, however, so that the actual commission came to nothing. Berlioz went ahead and wrote Harold anyway, but Paganini never performed it. In fact, Paganini did not even hear Harold until 1839, when he was so moved by it that, according to Berlioz’s memoirs, he knelt down in front of Berlioz and kissed his hand. The famous violinist was seriously ill at this time, and, having lost his speaking voice owing to a throat ailment, relied on his son as an interpreter. Two days later, the son brought a letter in which Paganini announced his gift of 20,000 francs to Berlioz so he could write a new major work. In the preface of the finished score, Berlioz stated, maybe a bit too optimistically: There is no misunderstanding the genre of this work. Although it makes frequent use of voices, it is neither a concert opera nor a cantata, but a symphony with chorus. A symphony with chorus – this certainly sounds like Beethoven’s Ninth, which, to Berlioz, was unquestionably the ultimate musical masterpiece and a major influence in several of his works. But Berlioz’s symphonic concept went significantly beyond that of Beethoven’s Ninth. In the Ninth, the chorus and the soloists intervene only in the last movement, the first three having no literary program at all. In Roméo, on the other hand, four of the seven movements include singing, and the entire work is based on a literary work. Yet, Berlioz didn’t set any part of Shakespeare’s play to music (with the exception of Friar Laurence’s speech). In particular, the lovers Romeo and Juliet do not sing. As Berlioz explained in his preface: If, in the famous garden and cemetery scenes, the dialogue between the lovers, the asides of Juliet and the passionate transports of Juliet are not sung, if the duets of love and despair are entrusted instead to the orchestra, the reasons are numerous and easily grasped. Firstly, and this reason alone would be sufficient justification for the composer, it is because he is writing a symphony and not an opera. Secondly, duets of this kind have been treated vocally thousands of time before by the greatest masters, making it wise, therefore, as well as unusual, to attempt another mode of expression. In addition, the very sublimity of this love story made its realization so fraught with pitfalls for the composer that he had to give his imagination greater freedom than the precise meaning of sung words would have allowed. Consequently, he turned to the language of instruments, a language far richer, less restricting, more varied and, by its very vagueness, incomparably more powerful. Tonight’s concert will feature the love scene from Roméo, which is the third of the seven movements. In the complete performance, this movement begins with a brief chorus where “the young Capulets, leaving the hall, pass by singing fragments of the dance music.” The movement is structured by the repeated statements of a single melodic refrain; in between, violas and cellos, then violins, and finally woodwinds play their various strains of magical beauty, separated by short agitated interludes and an instrumental recitativo (cellos). It is like a real dialogue between two lovers; in fact, British musicologist Ian Kemp has shown in a recent study how the music corresponds, almost line by line, to Shakespeare's balcony scene. The most striking evidence for this may be found, perhaps, during the last return of the refrain, when the lyrical melody is angrily interrupted by the violins. Here the Nurse is calling for Juliet: “Madam! Madam!” Eventually, the music fades into silence as the lovers part; the refrain becomes fragmented and completely disintegrates at the end. Flute Concerto (1926) by Carl Nielsen (Sortelung, Denmark, 1865 – Copenhagen, 1931) It has taken the international music world a long time to acknowledge Carl Nielsen as one of the major composers of his time. A towering figure in his native Denmark, he has not won a constant place on American concert programs until relatively recently. Nielsen belonged to the “pre-modern” generation of Debussy, Mahler, Strauss, and Sibelius, all born, like him, in the 1860s, one or two decades before the members of the more radical Schoenberg-Stravinsky-Bartók generation. By the 1920s, Nielsen’s contemporaries were either dead (Debussy and Mahler) or had stopped composing (Sibelius); Strauss had turned his back on his earlier experiments and was writing mainly operas in a post-Romantic idiom. Nielsen was almost alone in his generation to move forward in the years after World War I, developing a style based on a personal blend of traditional and modern elements. Nielsen wrote his Flute Concerto (1926) after completing the last of his six symphonies. He had written a Wind Quintet four years earlier, and he decided to write a concerto for each of the players who had been involved in the first performance. In these concertos, he intended not only to give each instrumentalist a solo work in which to shine, but also to portray their individual personalities. This may explain the great difference in tone between this work and the only other wind concerto Nielsen completed, the one for clarinet (1928). That work’s dedicatee, Aage Oxenvad, must have been a rather irascible person, while the flutist Gilbert-Jespersen was said to possess a “fastidiously refined” character, and to be a great lover of French music – traits quite evident from Nielsen’s music. Gilbert-Jespersen’s “intense lyrical strain” and especially his “robust sense of humor” are also amply reflected in the concerto. The Flute Concerto is in two movements and follows classical musical forms (sonata and rondo). The themes are often of classical simplicity, yet his use of harmony and sound color is entirely novel. Neither tonal in a traditional sense nor “atonal” as Schoenberg, Nielsen’s music moves freely from key to key, as if searching for the right one, and mixes conventional sonorities in an utterly non-conventional way. The Flute Concerto uses a relatively small orchestra but Nielsen combines his reduced forces with great ingenuity. His fondness for the timpani is evident in many places; the trombone glissandos in the second movement are greatly humoristic. (As Jack Lawson writes in his book on Nielsen (Phaidon Press, 1997): “In the Flute Concerto a trombone plays the role of a buffoon...and it acts as a foil to the genteel flute, a dig at Jespersen. It has been suggested that the humorous trombone, an instrument Nielsen had played in the military band, may represent the composer...”) The clarinet, in anticipation of the clarinet concerto Nielsen was to write, frequently challenges the flute soloist and engages in dialogues or duet-cadenzas with him (or her). All in all, the concerto manages to infuse a traditional framework with a rather innovative musical technique, and – most importantly in a concerto – with a highly virtuosic treatment of the solo instrument. It is undoubtedly one of the most important twentieth-century flute concertos. Ma mère l’oye (“Mother Goose”, 1908-1911) by Maurice Ravel (Ciboure, France, 1875 – Paris, 1937) Maurice Ravel’s Mother Goose has nothing to do with “Humpty-Dumpty” or “Peter, Peter, Pumpkin Eater.” His Mother Goose (or Ma mère l’oye) is a French storyteller, famous since 1697, the year Charles Perrault (1628–1703) published his collection of old and new tales in a book that became known popularly as “Mother Goose.” The collection contained, among others, the stories of Sleeping Beauty and Little Red Riding Hood. Ravel was inspired by Perrault’s collection as well as some other fairy-tale classics when, in 1908, he decided to write a short suite for piano duet, intended as a gift for Mimi and Jean Godebski, the children of his friends Cipa and Ida Godebski. He orchestrated the suite in 1911, and the same year, he expanded it into a ballet score by adding two new movements and a few interludes. The two new movements, “Prelude” and “Spinning-Wheel Dance and Scene,” precede the five taken from the piano suite. Ravel’s original idea in Ma mère l’oye had been to write a children’s piece that could be performed by children. He initially intended the work to be played by Jean and Mimi. In the end, the suite proved too difficult for the young Godebskis, and Ravel recruited two extremely gifted young pianists, Jeanne Leleu and Geneviève Durony (six and seven years old, respectively), for the premiere. His intention to write music that children would appreciate is reflected by the simplicity of the melodic writing, apparent even in the lush colors of the orchestral writing. In order to transform his suite of self-contained scenes into a coherent ballet, Ravel chose the tale of Sleeping Beauty as his central storyline, with the other stories appearing as dreams seen by the princess during her hundred-year slumber. The fairytale atmosphere is established in the Prelude with haunting horn calls, mystical string tremolos and some woodwind figures imitating the birds of the forest. Some of the melodies of the subsequent movements are also anticipated, such as the theme of the Sleeping Beauty’s Pavane and the sigh of the Beast (solo contrabass). Dance of the Spinning Wheel and Scene (Danse du rouet et scène) follows without a break. The young princess, playing with the spinning wheel, is wounded by the distaff and loses consciousness. The lively 6/8 rhythms and rolling sixteenth-note figures that have been associated with the spinning wheel, at least since Schubert’s song “Gretchen am Spinnrade,” are suddenly interrupted by a menacing woodwind motif. As the Princess falls asleep, the opening figure of the prelude returns to set the stage for the “five children’s pieces” (cinq pièces enfantines) that are about to begin. (Ravel slightly changed their order from the original, moving up the scene of Beauty and the Beast to follow directly after the Pavane.) Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty (Pavane de la belle au bois dormant). The pavane is a slow dance of Spanish origin to which Ravel had first turned in his early Pavane for a Dead Princess. In the original version, this new Pavane was rather brief, consisting of a single motif, soft and delicate, repeated by various instruments of the orchestra. Ravel expanded it in the ballet considerably, introducing a Good Fairy who gives a signal with her whistle (piccolo), whereupon two blackamoors appear on the stage. According to the scenario printed in the score: The Fairy entrusts them with the task of guarding the Princess’s sleep and disappears. The blackamoors come forward, toward the Princess and take ceremonial bows. They unfold a banner on which is written the name of the first tale to be told: “The Conversations of Beauty and the Beast.” Conversations of Beauty and the Beast (Les entretiens de la belle et de la bête) This story is very well known, but few actually remember the name of its author, Marie Leprince de Beaumont (1757). The conversation that inspired the music was reprinted in the score: “When I think of your good heart, you don’t seem so ugly.” “Oh, I should say so! I have a good heart, but I am a monster.” “There are many men who are more monstrous than you.” “If I were witty I would pay you a great compliment to thank you, but I am only a beast.” ... “Beauty, would you like to be my wife?” “No, Beast!” ... “I die happy because I have the pleasure of seeing you once again.” “No, my dear Beast, you shall not die. You shall live to become my husband.” ... The Beast had disappeared, and she beheld at her feet a prince more handsome than Amor, who was thanking her for having lifted his spell. The movement is in the tempo of a slow waltz. The Beauty is represented by the clarinet, the Beast by the contrabassoon. The two instruments take turns at first, and then join in a duet that becomes more and more impassioned. After a fortissimo climax and a measure of silence, an expressive violin solo (with harmonics) brings the movement back to its original tempo as the Beast is transformed into a handsome prince. For the ballet version, Ravel added a short interlude in which the blackamoors greet the Princess and unroll a new banner with the name of the next story: Tom Thumb (Petit Poucet) The score is preceded by a short excerpt from Perrault’s story: He thought he would be able to find the path easily by means of the bread he had strewn wherever he had walked. But he was quite surprised when he couldn’t find a single crumb; the birds had come and eaten them all. Tom Thumb’s wanderings are depicted here by a steady motion in eighth notes in the strings, over which the woodwinds play a quiet “walking” melody. The birds referred to in the story are indicated by a solo violin playing harmonic glissandos against a twittering flute and piccolo. The interlude following this scene, in which the blackamoors bring out yet another banner, contains a virtuoso cadenza for harp and celesta. Little Homely, Empress of the Pagodas (Laideronnette, Impératrice des Pagodes) The story on which this movement was based was written by the Countess d’Aulnoy, a contemporary of Perrault. The heroine is a beautiful princess who was made ugly by a wicked witch. She travels to a distant country inhabited by tiny, munchkin-like people called “pagodes.” (Eventually, as one might expect, she is restored to her original beauty and finds her Prince Charming.) As in the previous movements, Ravel concentrated on a single image from the story, and he wrote it down at the head of the score: She undressed and got into the bath. Immediately the pagodes and pagodesses began to sing and to play instruments. Some had theorbos [large lutes] made from walnut shells; some had viols made from almond shells; for the instruments had to be of a size appropriate to their own. The music is a study in turn-of-the-century Orientalism, with a lively pentatonic melody (playable on the black keys of the piano), colorfully orchestrated. In a more serious middle section, Little Homely dances with the Green Serpent (who will turn out to be Prince Charming, also disguised by an evil spell). The dance of the “pagodes” then returns, followed by an interlude that begins with a horn fanfare evoking a hunt. “Everyone withdraws in haste; the blackamoors hurry to lift up the canvas in the back,” revealing the fairyworld of the prelude, whose musical material briefly returns as a transition to: The Fairy Garden (Le jardin féerique) This movement does not seem to be based on any particular fairy tale. It is a celebration of the splendor of this miraculous garden, where the sun never goes down and everyone lives a blessed and happy life. The music is a single crescendo from a soft and low string sonority to a veritable feast of sound, resplendent with harp, celesta, and glockenspiel. In the ballet, this is obviously the moment where Prince Charming arrives and awakens the Princess, the two of them living happily ever after. ~Notes by Peter Laki The Oberlin Chamber Orchestra VIOLIN I Paul Hauer, concertmaster Ran Cheng, assistant principal Augusta McKay Lodge Josie Davis Yada Lee Julia Connor Elizabeth Cooke McKenzie Bauer Amy Hess Summer Lusk Henry Allison Hattie Ahn Alex Youssefian VIOLIN II Rachel Iba, principal Katherine Floriano assistant principal William Overcash Alex Watanabe Dorisiya Yosifova Will Watkins Tatiana Sutherland Emmy Tisdel Zhao, Jieying Yetto, Caterina Elizabeth CastroAbrams VIOLA Ryan Fox, principal Sarah Toy, assistant principal Kyle Aungst Becky Johnson Sarah Hill Cassie Tomás Brea Warner CELLO Youn Kyung Kim, principal Rose-Marie Bart, assistant principal Julia Henderson Joshua Morris Jennifer Carpenter Jaime Feldman Nathan Klein Sylvia Woodmansee BASS Shota Horikawa, principal Tyler Vallet, assistant principal Aaron Kanter Marco Retana FLUTE Amelia Dicks B Annie Gordon R Katherine Ma Elena Covarrubias OBOE Gigi Brady N Virginia McDowellB, R Leonardo Ziporyn HORN Kevin Grasel Katy Hatch N Ellen Hurley Melissa Kravets Hannah Parkins Valerie Sly B, R TROMBONE Matthew Marchand TIMPANI Kevin Scollo PERCUSSION Justin Gunter Holden Lai Michael Mazzullo HARP Bethany Wheeler CELESTA Marika Yasuda STUDENT MANAGERS Eric Anderson Aaron Plourde LIBRARIAN & MANAGER Michael Roest ENGLISH HORN Timothy Daniels B Gigi Brady R CLARINET Owen McTigue B Cesar Palacio Dustin Chung N Jarrett Hoffman R BASSOON Hunter Gordon B Molly Murphy Ben Roidl-Ward N, R Eric Yao CONTRA BASSOON Carl Gardner Winds and Brass are listed alphabetically. Superscripts indicate principal players: B = Berlioz = Nielsen R = Ravel N