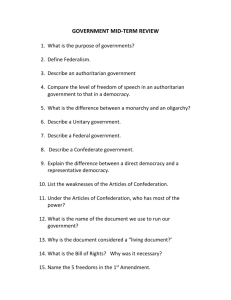

Introduction to Transitions to Democracy Unit

advertisement