AP Psychology

advertisement

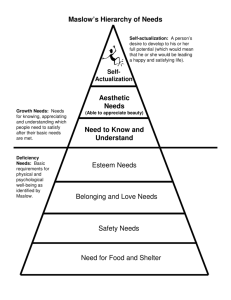

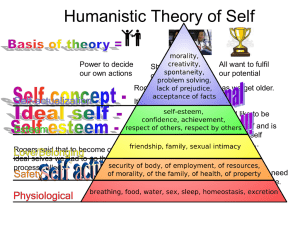

AP Psychology The Existentialist and Humanistic Theories In general, existentialism assumes that humans are free and future-oriented (teleology), that their subjective feelings of their personal experiences (phenomenology) are extremely important, and that they are concerned with the meaning of life while being acutely aware of their own impending deaths. They believe that humans have control over their own destinies since there is no master plan or essence of life. Humanists essentially adopt the same premises, but concentrate more on the idea that humans exercise their free will in an effort to realize their full potential and fulfill their needs for goodness. They believe that humans are genetically endowed with this sense of good rather than evil and that striving to manifest the good comes from within the person rather than from some external source. While the terms of each psychologist will differ slightly, they agree that individuals try to become the best version of themselves that is possible during their limited lifetimes. While many of the ideas presented below have some foundations in the theories of Adler and even Jung, one of the first psychologists officially categorized as a humanist is: Abraham Maslow (1908 – 1970) Maslow, a Jewish boy in a predominantly non-Jewish Brooklyn neighborhood, felt isolated from the other children and therefore retreated into himself and his studies from a young age. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin where he worked under the supervision of Harry Harlow in the latter’s early studies with rhesus monkeys to investigate primate behavior. Maslow was intrigued by the positive, dominant monkeys, speculating that their behavior seemed to result from an “inner confidence.” Once he left Wisconsin, he returned to NY and met many famous European psychologists who had left Nazi-invaded Europe. Among these psychologists were Alfred Adler, Karen Horney and Max Wertheimer, the Gestaltist. It was his influence that caused Maslow to develop his theory of self-actualized individuals. Maslow’s personality theory is based on the premise that humans have a hierarchy of needs that they strive to fill. He defines instinctoid needs as those innate but weak needs that are easily modified by the environment. His hierarchy of needs is usually depicted as a pyramid with the most basic (and therefore strongest) needs at the bottom and the more advanced (weakest) at the top: Weakest Self-Actualization Esteem (from self & others) Belongingness and Love Safety and Security Strongest Physiological Needs Some important points about the needs: The lower the need on the hierarchy, the more basic in terms of survival and the greater its influence on behavior The higher the need, the more distinctly human the need is and the later it emerges in the evolutionary process The higher the need, the later it emerges in an individual’s life and the greater the satisfaction in attaining it (resulting in peace of mind or deep happiness) The higher the need, the better environmental conditions required for its attainment Individuals may forego basic needs in order to succeed at some task The Self-actualization need was “the desire to become more and more what one idiosyncratically is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming.” Only a fraction of the population comes close to reaching self-actualization and it can never be fully attained. He believed that people don’t self-actualize for a number of reasons, including the fact that these needs are the weakest of the instinctoid needs, that people are afraid of the self-knowledge required to do so and self-actualization requires freedom to express oneself and to explore without restriction. He describes self-actualized people as those who: perceive reality accurately and fully demonstrate a greater acceptance of themselves, others and nature in general exhibit spontaneity, simplicity and naturalness tend to be concerned with problems rather than with themselves have a quality of detachment and a need for privacy are autonomous and therefore tend to be independent of their environment and culture exhibit a continued freshness of appreciation have periodic mystic or peak experiences (* see note below) tend to identify with all of mankind develop deep interpersonal relations with only a few individuals tend to accept democratic values and have a strong ethical sense have a well-developed, unhostile sense of humor are creative and resist enculturation “Peak experiences,” felt as self-validating and self-justifying, occur without the individual’s effort and are transcendent kinds of experiences. The universe is perceived as a unified whole that is both meaningful and perfect. The person loses the sense of time and space and there is a forgetfulness of self. The person experiences wonder, awe, humility and reverence for the experience; it tends to leave the individual with wholesome aftereffects that linger. Negative emotions disappear and some individuals experience a feeing of death and rebirth. George Kelly (1905 – 1967) Kelly is referred to as a cognitivist, an existential humanist, and a phenomenologist. He was born in Kansas to farming parents with a deeply religious background. He attended one-room schoolhouses and was tutored by his parents until he left home at age 13 to get a formal high school education in Wichita. He graduated college with degrees in math and physics. He became interested in social issues so he pursued graduate degrees in sociology and labor relations and a doctoral degree in psychology. Kelly realized that people were struggling with what to do with their lives – they were confused and seemed to have no direction, so he began a career in clinical psychology. Kelly had had no formal training in clinical psychology so he relied on what he had read, including the Freudian theories. In his practice, he made two career-changing observations: (1) people seemed very willing to accept any explanations he gave them for their behavior (even the “insights” he fabricated! Anything he told them that made them look at themselves caused some improvement in their situation) and (2) the perspective that people took in viewing a situation was more significant than the objective event itself. (His therapy methods are based on this.) His basic belief was that of “the person a scientist” – the notion that people go through life in an experimental fashion. His fundamental postulate amounts to the idea that a person’s processes are psychologically influenced by the way in which he anticipates events based on his own past experiences. He theorized that there are 11 corollaries to this postulate that describe/clarify the use of constructs in people’s lives. He postulated that we have constructs, or perspectives on the world and one’s self. (These are often called bipolar constructs because they represent dichotomous values.) Kelly believed that anxiety resulted when “you were caught with your constructs down” – when previously effective strategies did not work in a new situation. Faulty use of constructs can also lead to: Threat – fear that something will cause you to change the constructs you have Guilt – the result of doing things not in accordance with your constructs Aggression – trying to make reality align with your constructs Hostility – insisting that your constructs are working even when there is evidence they are not His therapy methods often utilize reconstruction, getting a patient to see things from a new perspective. He used role-playing where the patient took on the role of someone else in his life in order to “open up” to new points of view. He also used fixed-role therapy where he assigned a patient a detailed description of a pretend person. The patient then had to act like the fictitious person for a week or two in an effort to show the patient that he has control of his personality and can change it if he so chooses. Kelly developed an assessment instrument called the Role Construct Repertory Test (the “Rep Test”) (See activity handout) Rollo May (1909 – 1994) Rollo May came from a family in which his parents constantly fought and eventually divorced. After his graduation from Oberlin College, he traveled in Europe when he took a class from Alfred Adler. When he returned to the US, he enrolled in seminary school, not to become a preacher but to study the basic ideas related to human existence. He studied psychoanalysis and became a practicing psychoanalyst for several years. He contracted tuberculosis and lived in a sanitorium for 3 years, during which time he read books by Freud and Kierkegaard (a Danish theologian and philosopher who viewed humans as largely emotional and free to choose their own destinies.) This experience greatly influenced his subsequent theory of personality. May believes that we are victims of the “Human Dilemma,” the ability to see ourselves simultaneously as both object and subject. This means that we can see ourselves as a victim, influenced by the environment, other people, genetics and society. At the same time, we see ourselves as operators in the world, acting and reacting to the circumstances we encounter. (Note relation to social learning theory.) He outlined a loose stage theory of personality development: (1) innocence – the pre-egoic, pre self-conscious stage of the infant, concerned with survival needs (2) rebellion – childhood, adolescence stage when the ego develops by testing reactions in society (3) ordinary – the conventional stage of adulthood (4) creative – the existential, authentic adult accepting destiny and facing anxiety with courage His definition of anxiety is a threat to something in the “core” or “essence” of one’s personality or life. He believed it is essential to one’s life by creating the necessary tension to preserve human existence. He distinguishes between normal anxiety (anxiety that is a reaction to a real threat and which is in proportion to the threat) and neurotic anxiety (anxiety that involves repression, is disproportionate to the particular threat, or occurs with the inability to cope with the threat adequately.) May says the goal of therapy is to convert neurotic anxiety into normal anxiety. Another idea unique to May is that of the diamon, any natural function that has the ability to take over a whole person. Important ones include will and love. Will: organizing oneself to achieve one’s goals Love: necessary for human existence, a blending of 4 types: (1) sex – biological drive that needs to be satisfied (2) eros – the desire for union with another in a tender relationship (3) philia – friendship and enjoying another’s company (4) agapé – unselfish concern for another’s welfare Carl Rogers (1902 – 1987) Rogers’ family was a very devoutly religious, close knit group where friendships outside the home were discouraged because of the “questionable activities” of others. Rogers was an avid reader who kept much to himself. He developed a strong interest in science and went to the University of Wisconsin to pursue an agricultural degree, While there, he met many people of different backgrounds and religions; this experience caused him to declare his independence from his family’s conservative religious viewpoint. He earned master’s and doctoral degrees in educational psychology. His first clinical jobs worked mainly with children. During his experience as an intern in a Child Abuse Center, he learned that psychoanalysis was ineffective, that even “authorities” could not agree on what was the best way to help someone, and that looking for “insight” was often more frustrating than helpful. Rogers believed that people are inherently good and that they have an actualizing tendency that causes them to strive to reach their full potential. He emphasizes that the phenomenological field (a person’s own reality as he perceives it without regard to the physical world) is what determines a person’s behavior and that phenomenological world can truly be known only by the individual who experiences it. According to Rogers, what are most important to reaching self-actualization are positive regard and positive selfregard. Positive regard involves receiving things such as warmth, love, sympathy, care, respect and acceptance from the relevant people in one’s life. Positive self-regard is having this same sense of acceptance for oneself. Ideally, this positive regard would be unconditional positive regard (not dependent upon any specific behaviors or conditions of worth), but society often imposes conditions of worth which specify circumstances under which a child can receive the positive regard. Through repeated exposure, children internalize the conditions of worth and develop a conscience. Conditions of worth can be detrimental if they cause the individual to act in accordance with society’s values that may be discordant with the inherently good nature of the individual. For a person to become a fully-functioning person (Rogers’ word for self-actualization), one needs unconditional positive regard and congruence (a close match) between his real self (how he sees himself) and his ideal self (the person he wants to be.) Anxiety results when the real self and the ideal self do not align with one another, a state known as incongruence. One of Rogers’ major contributions to personality theory and to psychology in general is in the area of therapy. Rogers is known for client-centered therapy (also called person-centered therapy or Rogerian therapy.) In contrast to Freudian therapy where the doctor had all of the answers and the patient had to consult the expert for an answer to his problem, Rogers believed that individuals had their own solutions, but sometimes needed assistance in discovering them. Client-centered therapy is typified by reflection where the therapist mirrors back the thoughts of the patient. For example, if the patient said that he was having some trouble with his brother because his brother always came into his room when he wasn’t there, Rogers may restate the situation as “So what I hear you saying is that you are upset with your brother because he comes into your room without permission. What do you think you could do about that?” Rogers also developed a diagnostic technique known as the Q-sort where patients were asked to sort a deck of 100 cards into piles that reflected those most like them through a continuum to least like them. They then sorted the same cards according to what they wanted to be. The higher the correlation between the two sorts, the closer to congruence the person was.