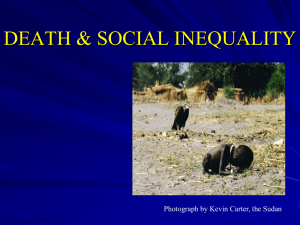

i. more questions than answers

advertisement