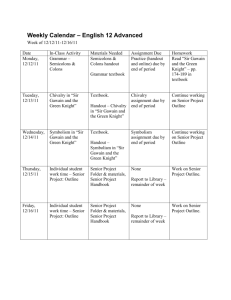

HOLLY: Gawain Analysis

advertisement

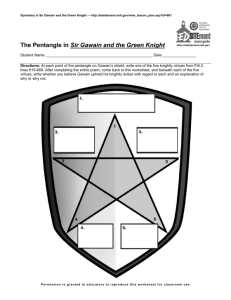

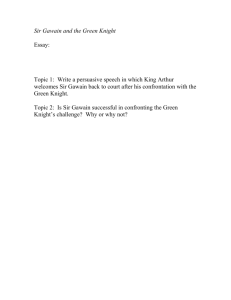

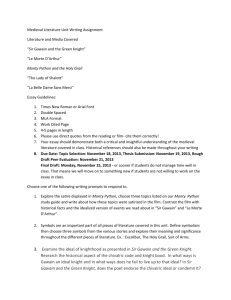

An Analysis of lines 556-669 of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight This passage powerfully introduces many key themes in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Courtliness, bravery, ceremony, and of course, the Pentangle, are all highlighted in this short extract. This is very visual passage. Much of this is derived from the poet’s varied use of colour: ‘Fyrst a tulé tapit ty t ouer þe flet, And miche watz þe gyld gere þat glent þeralofte’1 Red and gold (‘tulé’ and ‘gyld’) are the colours of Gawain’s armour and horse. Red being the complimentary colour of green, Gawain is immediately linked to the Green Knight. This link is almost paradoxical, however, as the two are simultaneously opposites and compliments. This could be a suggestion of Gawain’s double relationship with his challenger; as the Green Knight, he is Gawain’s enemy and opposer, and as Bertilak de Hautdesert, he is his friend and host. Red also symbolizes fire, and implies strength, vitality, and bravery, while gold indicates worth and nobility. But Gawain does not enter already clad in such colours, we see him being attired: ‘Þenne set þay þe sabatounz vpon þe segge fotez, His legez lapped in stel with luflych greuez, 1 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 568 - 569 Holly McFarlane With polaynez piched þerto, policed ful clene, Aboute his knez knaged wyth knotez of golde’2 The fact that we watch him being dressed highlights that the brave red and wealthy gold he wears is a costume; Gawain assumes these colours in an attempt to reflect and recreate what they symbolize, but they are not inherent in him. This is a fundamental difference to the Green Knight, who is ‘oueral enker-grene’ (150). It would not be particularly surprising for a character to be dressed all in green (it was a common and popular medieval colour) if his skin, his entire being, were not green also. This suggests something organic and natural about the Knight’s appearance; his image is a projection of his identity, not, as with Gawain, the other way around. Already, there is a sense that no matter how virtuous Gawain might be, he may still be unable to win against this mysterious figure. Much attention is paid to the detail of Gawain’s dress; the embroidery of his horse’s attire is described at length: ‘Enbrawden and bounden wyth þe best gemmez On brode sylkyn borde, and bryddez on semez’3 The alliteration of ‘b’ (a fairly strong consonant) gives these lines a chirpy rhythm, mimicking the sounds of the ‘bryddez’. Such dainty cheeriness and lightness is again in direct contrast to the rough, earthy, unstudied Green Knight, and the poet thus emphasises the inherent differences between the two opponents. There is a powerful interjection by the narrator midway through this extract: 2 3 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 574 - 577 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 609 - 610 Holly McFarlane ‘And quy þe pentangel apendez to þat prynce noble I am in tent yow to telle, þof tary hyt me schulde’4 There is no subtle introduction of key themes at this moment; the pentangle is important, and the poet ensures that his reader is aware of that. The use of ‘I’ is striking, not only because it is rare that the narrator bring himself so blatantly to the fore, but also because it reminds the reader that there is a strong persona and focus behind this writing; although different interpretations are possible to an extent, some of the writer’s themes cannot be ignored or manipulated. The image of the pentangle is one of such ideas, and the poet describes it unequivocally: ‘Hit is a syngne þat Salamon set sumquyle In bytoknyng of trawþe’5 He immediately introduces two key ideas encompassed in the pentangle; religion and truth; one must be true to chivalric ideals, God, and oneself. He then describes the never-ending nature of the pentangle: ‘vche lyne vmbelappez and loukez in oþer, And ayquere hit is endelez’6 The consonance in line 628 emphasises the infinite circles of the pentangle; the repetition of the ‘l’ sound mimics its never-ending loops. Already, the shield is established as a representation of perfect virtue; it depicts steadfast, consistent, unwavering devotion to truth. This description would likely be highly intimidating to Gawain, but the poet assures us: ‘Forþy hit acordez to þis kny t’7 4 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 623 - 624 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 625 - 626 6 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 628 - 629 5 Holly McFarlane Gawain’s virtue and truth are here deemed to be the qualities that distinguish him from others; if he has any weapons to use against the Green Knight, these are they. Although Gawain does not ultimately adhere entirely to the values shown on his shield, he displays enough honour and truth to save him from death. In this way, though undeniably human and flawed (which is vividly represented by his final wound, and afterwards by the green belt) he is still virtuous enough to succeed. The poet uses a lot of alliteration when describing Gawain’s virtues: ‘Fyrst he watz funden fautlez in his fyue wyttez, And efte fayled neuer þe freke in his fyue fyngres, And alle his afyaunce vpon folde watz in þe fyue woundez Þat Cryst ka t on þe croys’8 This repetition of the ‘f’ sound suggests Gawain’s virtue is organic. It links him linguistically with the number five, and therefore with the five virtues or corners his shield represents, implying their relationship is natural or inherent, as even the sounds of their names are intertwined. The alliteration is broken strikingly in line 643. Jesus, ‘Cryst’, is still set apart linguistically from Gawain; although the latter is often found ‘fautlez’, he is still human. This number five is very important in this extract. Not only is each of Gawain’s virtues fivefold, there are five of them altogether, five times five. This serves to highlight the interlocking nature of the shield; just as every power of five ends in five, so every point of the pentangle, every virtue, relies on, crosses, and encompasses another: 7 8 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Line 631 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 640 - 643 Holly McFarlane ‘Now alle þese fyue syþez, for soþe, were fetled on þis kny t, And vchone halched in oþer, þat non ende hade, And fyched vpon fyue poyntez, þat fayld neuer’9 Thus, the shield represents harmony, a balance of faith and loyalty between all the interconnecting lines. However, it is also notable that there are five distinct ‘poyntez’; although the virtues are irrevocably entwined, they still represent specific, separate ideas. After his exposition of the pentangle, the poet draws a swift, neat conclusion: ‘Þerfore on his schene schelde schapen watz þe knot Ryally wyth red golde vpon rede gowlez, Þat is þe pure pentaungel wyth þe peple called with lore.’10 Here, the images of red and gold return and combine with the idea of purity. We are reminded of the unattainable perfection of the pentangle, that although Gawain is possibly the character who encompasses most of the shield’s virtues, he can never fully realize them all. Thus, the poet simultaneously expresses the possibilities and limitations of humanity. 9 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 656 - 657 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Lines 663 - 665 10 Holly McFarlane