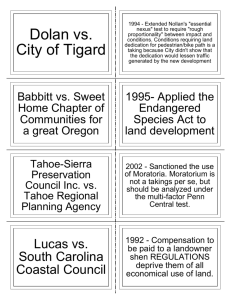

Takings 13 First English

advertisement