Warren Court and Red Scare Decisions

advertisement

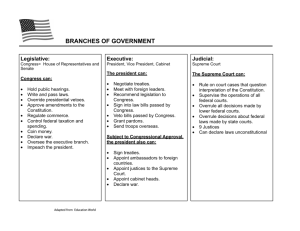

Running Head: WARREN COURT INCONSISTENCY The Warren Court and Inconsistencies in Regards to the Red Scare Decisions Greg Gimpelevich Georgia State University Abstract For a decade, the Warren Court made several controversial decisions regarding civil liberties, personal rights and freedoms. After some investigation into three primary cases of Watkins v United States, Barenblatt v United States, and Gibson v Fl. Legislature, all cases with similar facts it becomes increasingly difficult to determine the exact reason that the only decision the court did not overrule was the Barenblatt decision. This paper tries to analyze some of the possible motives and reasons behind the court’s decisions in the three cases. The Warren Court and Inconsistencies in Regards to the Red Scare Decisions During the 50s and well into the 60s, Congress had made certain decisive moves against possible Communists within the United States. With the enactment of laws such as the McCarren Act, the Communist Control Act, the Feinberg Law, and the more well-known Smith Act, Congress seemed to have broad authority to investigate “subversive activity.” Thus, with the Smith Act, the House Committee for Un-American Activities (HUAC) was born. This committee began to subpoena citizens and members of organizations in an effort to weed out former, present, and would-be communists. The Smith Act which, makes it illegal to “willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the duty, necessity, desirability or propriety of overthrowing or destroying the government of the United States…by force, violence or by the assassination of any officer,” became the basis for HUAC’s power to question and subpoena those that the committee thought may be involved with Communists. (18 U.S.C. 2004 § 2385). Osmond Frankel notes that at first, “the court refused to exercise its discretionary power to review federal convictions, particularly in the cases of writers known as the Hollywood Ten” (1973, 148). This refusal to exercise may have been heavily politically motivated as in stepping into the realm of adjudicating Congress, the Judiciary branch was gambling its power of jurisdiction. Since Congress is the official law-making body, they could have made certain laws barring the Court from ever being allowed to hear cases in this area. Later on, as cases became somewhat more complicated and prevalent, such as the case presented against eleven top officials of the then Communist Party in Dennis v United States, (which they lost), it became necessary for the Judiciary branch to step in. Most cases that were argued before the Supreme Court based their refusal to answer HUAC’s questions on the basis of the First, Fifth and or Fourteenth Amendments. The cases which this paper will compare and contrast are Watkins v United States (1957), Barenblatt v United States (1959), and Gibson v Florida Legislature (1963) and show that some justices, particularly Harlan, were inconsistent in regards to the rulings they made from certain cases, failing to stick to definite standards. In Watkins v United States, Mr. Watkins, was asked to answer certain questions about his dealings with the Communist Party. Many times over, in various forms of questioning he answered the questions “freely and without reservation” (354 U.S 178). Watkins openly admitted to having made contributions to Communist causes and signing petitions, all actions which may make one believe that he would be a member of the Communist Party. However, Watkins flatly rejected the accusation of his membership in the party by saying, “Since I freely cooperated with the Communist Party, I have no motive for making the distinction between cooperation and membership except the simple fact that it is the truth. I never carried a Communist Party card. I never accepted discipline and indeed on several occasions I opposed their position” (354 U.S. 178). After the line of questioning about Watkins’s personal matters was over, the committee soon turned to asking Watkins to name names of those he thought might be associated with said party. The subpoenaed refused to answer questions about those who he thought might be associated with the Communist Party. He was willing to answer questions about those who he knew to be members but refused to testify about persons who he was unsure of. The basis for his refusal was simple. Watkins did not believe that the Congressional Committee, in asking him to name names, was over-stepping its powers stating that the questions asked were “outside the proper scope of the committee’s activities,” and that “questions are not relevant to the work of the committee, nor does the committee have the right to undertake the public exposure of persons because of their past activities” (354 U.S 178). The committee held Watkins in contempt for refusing to answer questions, and the U.S. Attorney came back with a seven-count indictment. Watkins was then sentenced and jailed. Upon an attempt to appeal, the Court of Appeals for District of Columbia affirmed the conviction of the defendant. Upon appeal to the Supreme Court however, the justices overturned the ruling in a 6-1 decision with two justices (Burton and Whittaker) not participating in the ruling. Warren, in delivering the opinion of the court stated the following: The power of the Congress to conduct investigations is inherent in the legislative process. But, broad as is this power of inquiry, it is not unlimited. There is no general authority to expose the private affairs of individuals without justification in terms of the functions of the Congress. No inquiry is an end in itself; it must be related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task of the Congress. Investigations conducted solely for the punishment of those investigated are indefensible (354 U.S. 178) Although he was a justice who eventually “became the spokesman for judicial restraint,” Justice Frankfurter concurred on the decision under different standards. (Goodman 1971, 169). Frankfurter believed that the scope of inquiry of HUAC was highly unclear and in some cases ambiguous – too ambiguous for a subpoenaed party to understand relevance of questioning. Justice Clark, in an opinion of dissent stated that it is not the “[job of the] Court to interfere with the committee system of inquiry. So long as the object of a legislative inquiry is legitimate and the questions propounded are pertinent thereto. To hold otherwise would be an infringement on the power given the Congress to inform itself” (354 U.S. 178). For the most part, it seems that Justice Clark was arguing judicial restraint in place of Frankfurter, wanting to uphold the idea of separation of powers. In the next case, Barenblatt v United States the precedent that was set by so many cases before to overturn convictions of refusing to answer questions was broken. Having had his job terminated by the university prior to the hearings but after getting subpoenaed, Mr. Barenblatt “came to the hearings as a private citizen” (Weinberger 1962, 101). During this time, HUAC was apparently investigating the infiltration of Communism into the public field of educational institutions. Barenblatt was worried that “were he to answer any questions, his ability to earn a living would be seriously jeopardized” (360 U.S. 109). Instead of choosing to argue the “contempt of Congress” charge based on 5th amendment grounds or fourteenth amendment grounds, Barenblatt chose to rely solely based on the precedent set forth by Watkins v United States. His lawyer of course argued concepts of vagueness of authority of HUAC, (i.e. the ambiguity of the Smith Act), as well as the notion that the questions that the Committee asked were of little or no relevance to the mission statement. Perhaps this one was of the reasons that the holding in this particular case was so close, 5-4 in favor of affirming the charges brought against Lloyd Barenblatt. While Watkins was open and forthcoming about his associations with the Communist party, Watkins did not want to reveal any associations that others may have had with the Party. Barenblatt himself, however, “expressly disclaimed any reliance on 5th amendment protection against self incrimination and made no objections to inquiry on first amendment grounds” [although his lawyer did try and argue that for him] (Vestal 2002, 58). It is very possible that Barenblatt’s seeming audacity to simply argue based on lack of relevance to answer questions about himself, is what affirmed his conviction with such a close holding. Lucas Powe cites that, “there is a big difference between the first and the fifth amendments as the latter affords a witness the right to resist inquiry in all circumstances,” while the former does not. (2000, 143). In the majority opinion, as delivered by Justice Harlan, (who oddly enough was in the majority opinion reversing the Watkins decision), believed Barenblatt to be “clearly informed of the subject matter and the pertinent nature of the questions” (Vestal 2006, 59). Justice Harlan here seems to be the most inconsistent of the Justices considering that he is failing to uphold free speech, something of which he tended to be a huge proponent such as allowing one particular person to use the word “Fuck” in a sign that read “Fuck the Draft” being displayed by a men near a courthouse (Leahy 1999, 121). In his book The Rights We Have by Osmond Frankel, the author states the court’s blatant disregard for its own precedent. “While the court had, in the Watkins case stated that no committee of Congress had the power to inquire merely to expose, it late ruled that the Court could not inquire into the actual motivations of such committee in asking particular questions” (1973, 52). This was almost a turn back to exercising judicial restraint in the pre Dennis v United States cases. The dissenting opinions, who were generally recognized as the more liberal of the nine, (Black, Douglas, Brennan and the Chief Justice, Warren), opposed the decision with the opinion written by both Black and Brennan. They believed that “it is difficult at best to make a man guess – at the penalty of imprisonment – whether a court will consider the State’s need for certain information superior to society’s interest in unfettered freedom” (360 U.S 109). The dissenters believed Congress to be overstepping its bounds heavily, almost equating the Committee’s actions to a trivial search for anyone “who was ever even innocently belonged to the Communist Party” (Leahy 1999, 123). Black was a generally fair minded Justice who, if ever voted to overturn a conviction (in cases such as Yates or Noto), did so based only on insufficient evidence as presented by the committee. Furthermore, in The Rights We Have Black is quoted as saying “‘to deny that exposure and punishment are the aim of this committee would be to ignore its own claims and reports’” (Leahy 1999, 150). Even more so, Black tried to further attack the ambiguity as expressed through terms such as “propaganda” and “Un-American” and exactly how those terms are defined. Andrew Weinberger points to an especially interesting portion of Black’s dissenting opinion where he proposes that “the real interest in Barenblatt’s silence is that the interest of people as a whole to join organizations to advocate causes and make ‘political mistakes’ without later being subjected to government penalties is in danger” (1962, 101). Harlan’s attempt to fight back and justify his ruling was interesting considering that he used a different precedent that was set by Dennis v United States. Harlan’s premise focused on the idea that “if sending Communist Party members to jail for advocating overthrow of government does not violate the 1st amendment as was held in Dennis v United States, then there should be no violation of 1st amendment for sending them to jail for being active members of the party,” (as the party’s ideals were advocating violent overthrow of the established government) (Leahy 1999, 124). Douglas’s attempt at dissenting was a short but very eloquent phrasing stating that “we legalize today, guilt by association” (Leahy 1999, 124). It was difficult for Black and Douglas to see Barenblatt lose the case particularly, as Powe notices, they were generally regarded as “absolutists when it comes to issues of free speech” (Powe 2000, 143). It seems that Harlan was simply unwilling to scrutinize committee proceedings, perhaps for fear of political sanctions and losing jurisdiction in such matters. The last case where one can see precedent being ignored is Gibson v Florida Legislature. In this particular case it was technically not only Gibson who was under investigation but also, in effect the entire Miami branch of the NAACP. The NAACP case here was actually one of many, which stemmed from the Southern states’ attempts at curbing desegregation of schools. Because none of the school boards would do so voluntarily, the NAACP as well as other civil liberties organizations had to bring constant suits against them. In an earlier case where Alabama was taking on the NAACP, Harlan supported the organization because he said, in those cases “those exposed often met financial ruin or public hostility” (Leahy 1999, 125). In Gibson v Fl Legislature, however, Harlan decided to dissent. The facts of the case are fairly straightforward. In an attempt to ruin the credibility of the NAACP, the President of the Miami Branch of the NAACP was ordered to appear before HUAC. This time HUAC was investigating Communism in other organizations. The committee then asked him to produce membership records of his branch. When Gibson denied the request to produce said records, he was held in “contempt of Congress.” This case however, was argued under 14th amendment rights which allow for due process of law as well as the 1st amendment rights to freedom of speech and association. This is really the one case that throws most people off of finding a true voting pattern as Black and Douglas wrote separate concurring opinions and Harlan, Clark and Stewart wrote a separate dissenting opinion while Justice White wrote yet another separate dissenting opinion as well. Melvin Urofsky also point out an interesting irony in that the “chief exponent of judicial restraint on the bench at the time in 1963, Justice Frankfurter, was replaced by the very activist Justice Goldberg,” which, in all likelihood was the pivotal liberal 5th vote in the 5-4 decision made by the court to overturn Gibson’s “contempt of Congress” charge. (2001, 69). In the majority opinion, the activist Justice Goldberg, along with four others claimed that “the record was insufficient to show a substantial connection between the Miami branch of the NAACP and Communist activities” (372 U.S. 539). Although it was Justice Goldberg, a liberal who replaced a conservative, who was seen as the swing vote, Melvin Urofsky believes Potter Stewart to be the deciding vote. Stewart’s expressed opinion stated that in Gibson v Fl Legislature “there was a significant difference between Communist and Civil Rights Leaders” (2001, 123). Justice Black had the same basic ideas as the rest of the pro NAACP Justices, arguing the 14th amendment even stronger and in more broad terms. Justice Douglas wanted to specially cite that Congress had once again overstepped its bounds, had no “power to legislate membership in a lawful organization and could not probe relationships in such organizations regardless of the legislative purpose sought to be served” (372 U.S. 539). It is odd however that Justice Harlan would dissent in this case considering that he upheld the NAACP in the Alabama case only years before. It can be argued that in a sense he wanted to maintain the position he took in the Barenblatt case. His idea on jailing those advocating overthrow of a government and those who choose to be members of an organization that is attempting an overthrow of a government could have been his motivation for making his dissent. However, it would still not adequately explain his support of the NAACP in the Alabama case. White’s dissent does not come as quite a big shock because as Urofsky points out, “White started as a liberal pragmatist and became conservative as years rolled on” (2001, 69). His dissent seemed to be written out of an almost fear for the Communist Party stating that, “the net effect of the Court’s decision was to insulate from effective legislative inquiry and preventive legislation the skills of the Communist Party in subverting and eventually controlling legitimate organizations” (372 U.S 539). Overall it is not difficult to ascertain possible motives for the decisions the Justices made. Perhaps Harlan was in-fact worried that Congress would limit the jurisdiction of the Court and voted in dissent. Even the activist Justice Goldberg was “always fearful that the court would injure itself by taking controversial issues” (Urofsky 2001, 69). None of these are definite clear cut issues, which is why justices will have such differing opinions. Most Justices however, do not change their adjudicating philosophy as much as the Warren Court needed to. I think that in order for the preservation of our nation, many of the justices purposely needed to change some of their voting tactics or rationales in order to keep a narrow balance. If the Court were consistently making decisions in favor of individual rights and never in those of Congress, then they would have lost many of their jurisdictional privileges. Similarly, if they were to constantly be making advances for abridgement of those same personal freedoms, it is likely they would have been impeached for using too much of their personal ideology. The career of a Supreme Court Justice is in essence a delicate balancing act. Such anomalies in judgment of cases can thus be forgiven for the sake of stability. Refrences Barenblatt v United States 360 U.S. 109 (1959) Watkins V United States 354 U.S. 178 (1957) Gibson V Fl Legislature 372 U.S. 539 (1963) Advocating Overthrow of Government; 18 U.S.C. § 2385 Epstein, Lee & Thomas G. Walker. (2006) Institutional Powers and Constraints. Washington D.C.: CQ Press. Frankel, Osmond K. (1974). The Rights We Have. New York: Thomas Y Crowell Company. Goodman, Elaine & Walter. (1971). The Rights of the People: The Major Decisions of The Warren Court. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux Leahy, James E. (1999) Supreme Court Justices Who Voted With the Government. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc. Powe, Lucas A. Jr. (2000) The Warren Court and American Politics.Massachusets: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Urofsky, Melvin I. (2001) The Warren Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara, California: ABC Clio Supreme Court Handbooks Weinberger, Andrew D. (1962) Freedom and Protection: The Bill of Rights. San Francisco: Chandler Publishing Co. Vestal, Theodore M. (2002) The Eisenhower Court & Civil Liberties. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers.