Types of Government Agency Records

Types of Government Agency Records

Definitions

“Government” includes all levels from federal to local.

“Agencies” includes all agencies including legislative bodies and all levels of courts.

“Records” includes all information generated, collected, and maintained by government agencies.

“Public” is, strangely enough, another word for the private sector, as well as denoting availability of government records to the private sector.

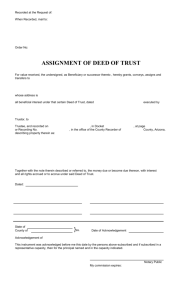

“Document” is a record that is filed with a government agency using paper or a paper or electronically filed form.

Types of Records

“Records” is a generic term that is not useful in describing the actual stuff that government agencies hold.

For example, a legislative bill has little in common with a tax return or a deed, but all are considered

“records.” Records may or may not constitute “information” to the government agency. A land recording office has no interest in any but a small portion of the content of a deed, mortgage or other document submitted to the office. The recorder’s job is to see that an image of the document is maintained and available as needed.

In order to fashion legislation to address personal information privacy concerns, the drafters need to be aware of the different forms of records that may contain such information. Records can be distinguished in a number of ways, as follows:

1. Paper vs. Electronic Document

Paper documents are generally considered to include forms and legal instruments filed or recorded by the public with a government agency. Electronic documents are usually just an electronically transmitted version of a paper document.

2. Formatted vs. Unformatted Document

A typical formatted document is a form that is filled out by, for, or about a member of the public, that is, a person or an organization. Forms can be filled out by a person, such as voter registration, or filled out on behalf of a person, such a birth certificate.

A typical unformatted document is a deed, mortgage or articles of incorporation. Although the content of this type of document may be determined by law, the actual placement of information on the document is up to the preparer. Some documents are partially formatted. For example, a deed can usually be depended on to contain its date on the first page.

3. Data vs. Document

“Data” is the computerized world’s word for orderly content. Your name and address on a document is data. A document itself is not data. This distinction is important to consider when deciding what should and should not be disclosed on the public record.

4. Formatted vs. Unformatted Data

Formatted data is the kind that computers use; it is fielded information that can be distinguished by its definition. For example, the Vermont transfer tax form has a box for social security number. This data in the document could be translated into formatted data in a computer system by entering it into its own field on the computer.

Unformatted data is the kind that is contained in deeds and mortgages, which have no boxes or fields. The name of the grantor is somewhere within the content of the document, but it takes the eyes of a person to detect where the information resides. Unformatted data in a document can be translated into formatted data on computer also, as when a grantor name is indexed.

5. Government Generated v. Private-Sector Generated

Many records are generated by the government itself, such as legislation and minutes of county council meetings. These records may contain information compiled from other sources, and the information may be about individuals.

February 26, 2003 PRIA 1

Many other records arise from the private sector, such as land records, UCC filings, and articles of incorporation.

6. Original v. Compiled Documents

Real estate documents, UCC filings and articles of incorporation are original documents created by the public and maintained without change by the government agencies that hold them.

Parts of motor vehicle records and. FBI rap sheets contain information that has been complied from other original record. Motor vehicle records contain summaries of accident and traffic infractions; FBI rap sheets contain summaries of arrest, court and incarceration records from local, state and federal sources.

7. Index vs. Full Record

There are two types of indexes created by government agencies to help locate records:

a. Index to document

UCC and grantor/grantee indexes are obvious example of a reasonably “pure” document index, that is, one that has a minimum of actual document data in it and that points to the real record of interest, the document. It is always necessary when using this type of index to get a copy of the record to know what it contains.

In addition to the bare information necessary to point to the relevant documents, indexes can contain other data. For example a court index may in fact be the docket, a summary record of all the actions taken with respect to a particular case. This expanded index record can then point to the various complaints, answers and other filings in the case so that you can request just the documents that fit your particular need.

b. Index to data

If the information is already in data form, as defined above, the second step is to drill down in the computer files to the full data. For example, an assessor’s property record containing information about your residence is a data record you can locate through indexes of property addresses or owner names.

Types of Data

In addition, the types of data contained in documents can be distinguished, as follows:

1. Required

The real estate statutes of many states require a deed or mortgage to specify the marital status of the parties who are individuals due to other state law considerations, such as in Arizona, a community property state. In Arizona, marital information therefore appears in the public record.

2. Discretionary

The new UCC1 form as designed in 1998 contained a box titled something like “Taxpayer ID” although the new Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code did not require the social security number of an individual debtor to be entered on the form (except in the North and South Dakota versions). Financial institutions persisted in entering the SSN, so the form has been redesigned to eliminate the heading on the box.

3. Inadvertent

Many financial institutions persist in entering the SSN of individual debtors on mortgages to be recorded.

There is no good reason for this practice, and it may even be an unacceptable practice under Gramm-

Leach-Bliley. Since the mortgage is public record, the SSN inadvertently becomes public record too.

Conclusions

Statutes that purport to make confidential certain information in the hands of government need to identify and deal with all these permutations of types of records and data. If the information is data, it is simple to redact. If the data is embedded in an unformatted document, it may be impossible to redact, but it may be possible to keep the document from being recorded in the first place.

February 26, 2003 PRIA 2