Individual demand

advertisement

3/9/2016

Page 2

CHAPTER 5: Pricing and demand

In 1993, Mars began exporting its popular Snickers chocolate bar to Russia. They had no experience in Russia, so they

based the Russian price on the price in Great Britain. One local distributor began selling the candy to retailers for much

higher prices--and pocketed the difference. Some months after her misdeeds were discovered, Mars did a demand

study that verified what the distributor already knew---that customers were willing to pay six times the amount charged

in Great Britain due to the novelty of the candy and the fact that they were the first western-style candy bar in Russia.

Unfortunately, by the time the mistake was discovered, foreign competitors had already entered the market and the

demand for Snickers dramatically declined.

The purpose of this chapter is to teach you how to price products and to avoid mistakes like this. We introduce demand

curves as a way to describe consumer behavior for the purpose of making profitable pricing decisions.

Aggregate or market demand

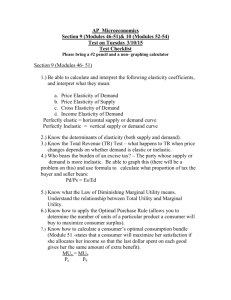

There are two distinct types of demand curves: aggregate and individual. Aggregate demand curves are important for

understanding group or aggregate behavior, and individual demand curves are important for understanding individual

behavior.

Aggregate demand can best be described with an example. Suppose that there are nine buyers, each of whom wants to

buy a single unit of a good. To construct a demand curve, simply arrange the buyers by what they are willing to pay,

e.g., ($6, $5, $4, $3, $2, $1). At a price of $6, only one buyer will purchase1; at a price of $5, two buyers will purchase;

at $4, three buyers; and so on. At a price of $1, all six buyers will purchase the good. An aggregate demand curve is

the relationship between the offered price and the number of purchases made by this group of consumers. In the Table

below, we plot this aggregate demand curve.

MR

6

4

2

0

-2

-4

MC

1.5

1.5

1.5

1.5

1.5

1.5

Aggregate Demand

8

Price

Price Quantity Rev.

6

1

6

5

2

10

4

3

12

3

4

12

2

5

10

1

6

6

6

4

2

0

0

2

4

6

8

Quantity

Table 3: Aggregate Demand Curve

Demand curves present sellers with a dilemma. Sellers can raise the price and sell fewer units, but earn more on each

unit sold. Or they can lower price and sell more, but earn less on each unit sold. This fundamental tradeoff is at the

heart of pricing decisions, and is resolved by using marginal analysis because pricing is an extent decision. To sell

more, you have to reduce price.

Definition: The marginal revenue (MR) is the change in total revenue associated with an extra unit sold.

Marginal revenue is the benefit of producing and selling one more unit. As long as marginal revenue is larger than the

marginal cost, profits increases with each extra unit sold. This relationship underscores the usefulness of marginal

1

Do not get distracted by the fact that at a price of $6, the buyer is being charged a price exactly equal to his value, and

is thus earning no surplus. At a price of $6 the buyer is exactly indifferent between buying and not buying. This is an

artifact of the use of whole numbers to describe prices and values. For convenience, imagine value is a fraction above

the price, so that the buyer will purchase

2

3/9/2016

Page 3

analysis. You don’t need to know the entire demand curve to know what whether to sell another unit, only the

marginal revenue at the current price.

Proposition: If marginal revenue is greater than the marginal cost then marginal profits are positive, and total

profits increase if you sell one more unit. Sell more (reduce price) if MR>MC and sell less (raise price) if MR<MC.

In the table above, if marginal cost were $1.50, you would want to sell three units; if marginal cost were $2.50, you

would sell two units units. Note that the question “Should I sell less or more?” is equivalent to the question, “Should I

raise or lower price?”

Going back to the problem of selling Snickers in Russia, the company failed to realize that the marginal revenue was

much lower than the marginal cost. If Mars had experimented with different prices, or done marketing studies they

would have discovered that price was too low for Snickers in Russia.

Different prices for different consumers

At the profit-maximizing price of $4, only three of our consumers decide to purchase. Those consumers with values of

$3 and $2 do not purchase the good even though their values exceed the $1.50 marginal cost of producing the goods.

These two consumers represent two unconsummated wealth-creating transactions. The one lesson of business is to

figure out how to profitably consummate them.

The trick is to find a way to sell at a lower price to these low-value consumers without also reducing prices to the highvalue consumers. If you could sell to each of these two low-value consumers at a price of $2, then you would earn $1

more. To do this you have to identify the low-value consumers, figure out a way to lower price to them, and prevent

them from re-selling to high-value consumers. You have to guard against the possibility that offering a unit for sale at

a lower price will “cannibalize” sales to the high value customers. In Chapter 9, we will discuss how to implement

schemes like this.

Discussion Question: Suppose you have nine consumers who make up an aggregate demand curve with values of $4,

$5, $6, $7, $8, $9, $10, $11, and $12. What is the revenue-maximizing price? Now suppose that old people make up

the group of with values of $4, $5, and $6 and young people make up the group with values of $7, $8, $9, $10, $11, and

$12. Design a price discrimination scheme.

Answer: The revenue-maximizing price is $6 for total revenue of $42. But if you can charge different prices to old and

young people, then charge a $4 price to the old people for revenue of $12 and charge a $7 price to the younger group

for revenue of $42. With this pricing scheme total revenue is $54.

Discussion Question: Is this kind of price discrimination wrong, or unethical? (HINT: does it move us towards or

away from efficiency?)

Individual demand

Individual demand curves describe the behavior of a single representative customer who demands more than one unit

of a good. Although individual demand curves look similar to aggregate demand curves, there are several important

differences that affect pricing decisions.

Again, the easiest way to describe individual demand curves is with an example. Consider a single customer who is

willing to pay $6 for the first unit, $5 for the second, $4 for the third, and so on, as above. IF the price is set at $6, our

consumer will purchase one unit; if the price is set at $5, two units; $4, three units; and so on. Each point represents the

value that our single customer places on each unit consumed, e.g. the consumer values the first item at $6; the second at

$5, and so on. This differs from the aggregate demand curve, where each point on the curve represents a different

consumer with a different value for a single unit of the good.

Discussion Question: Why does the individual demand curve slope downward? That is, why does an individual’s value

decline with increased consumption of the good?

Answer: Eventually, after consuming enough of a good, your desire for the good decreases. This means your

marginal value, the value you place on an extra unit of the good---and the amount you are willing to pay for it--declines with each purchase. For example, a retailer who purchases from a manufacturer may find that the first few

items are relatively easy to sell, but to sell more, she may have to lower the price, “hold” the item in inventory for a

3

3/9/2016

Page 4

longer period of time, or spend money promoting the item. All of these activities reduce the amount that the retailer is

willing to pay for additional items.

Discussion Question: Why do newspaper vending machines allow buyers to take more than one paper while soft drink

vending machines dispense just one can of soda at a time?

Answer: For most people, the marginal value of a second newspaper is zero. So even when given the chance to take a

second newspaper, most consumers won’t do it. 2 But the marginal value of a second can of soda is positive. Many

consumers would take the extra soda if given the chance.

Different prices for each unit consumed

If a seller is setting a single price, it doesn’t matter whether she faces an aggregate or an individual demand because the

profit calculus is the same. If the marginal cost is $1.50, she will sell all items where MR>MC, in this case three units

at a price of $4. And just as in the aggregate demand curve, at the optimal price, there are unconsummated wealth

creating transactions. At the profit-maximizing price of $6, our representative consumer purchases only three items.

The low-value “extra” goods – those worth $3 and $2 – do not get purchased even though the consumer would pay

more for these “extra goods” than the marginal cost of producing them. These two extra units represent

unconsummated wealth-creating transactions. Again, the one lesson of business is to figure out how to profitably

consummate them.

The trick to profitably selling more units is to find a way to sell these additional units, without dropping the prices of

the earlier units. There are several ways to do this.

i.

You can offer volume discounts, e.g. one good for $12, the second good for $11, and so on….

ii.

You can use two-part pricing. Charge a low enough unit price so that there are no unconsummated

transactions (in this example, $1.50) and then bargain over how to split the resulting consumer surplus.

The consumer’s total value for 5 units is $20 ($6+$5+$4+$3+$2+$1) which costs only $7.50. Bargain

over how to split the $12.50 worth of surplus to split between buyer and seller.

iii.

You can bundle the goods by offering five units at a bundled price of $20. The consumer values the first

good at $6; the first two goods at $11; the first three at $15; the first four at $18, and the first five at $20.

Notice the similarity of bundling to the timber tract pricing discussed in Chapter 4. If you set a bundled price of $20,

then the consumer demands the whole bundle, just as the logger has an incentive to harvest the whole tract under a

fixed payment of $15,000. To see this, construct the logger’s individual demand curve for trees. Recall that the tract

has a mix of fifty fir trees valued at $100, and fifty pine trees valued at $200. If we charge a price of $200, the logger

“consumes” fifty trees and we earn $10,000 but if we reduce the price to $100, the logger consumes one hundred trees

but our earnings don’t change. We can make more money by bundling the 100 trees together and selling them for

$15,000. By

This illustrates a very important lesson for pricing. When bargaining with a customer, do not bargain over unit price;

instead bargain over the price of a bundle. First figure out how much the consumer would demand if price were set at

marginal cost, and then bargain over the bundled price for this amount.

Summary

To summarize, the distinction between aggregate and individual demand is not important if you trying to determine a

single optimal price. The tradeoff—lowering price to sell more units—is the same for both aggregate and individual

demand curves, and leads to the same optimal price, where MR=MC. However, if you want to do better than this, you

need to be able to sell goods at different prices. This allows you to avoid the tradeoff between pricing high but selling

fewer items, and pricing low and selling more.

This practice is called price discrimination. Price discrimination schemes depend on whether you are facing an

aggregate or an individual demand. With aggregate demand, you charge different prices to different consumers; but

with individual demand, you charge different prices for each unit consumed.

2

One student said that he takes several Sunday papers at once because the papers contain valuable discount coupons.

4

3/9/2016

Page 5

Summary of main points

Aggregate or market demand is the number of units will be purchased by a group of consumers at a given price.

Individual demand is the number of units an individual will purchase at a given price.

Pricing is an extent decision. Reduce price (increase quantity) if MR>MC. Increase price (reduce quantity) if

MR<MC. The optimal price is where MR=MC.

At the optimal price, there are unconsummated wealth-creating transactions.

For an aggregate demand curve, consummate these transactions by charging different prices to different groups of

individuals.

For an individual demand curve, consummate these transactions by charging different prices for different

quantities consumed.

When bargaining with a customer, do not bargain over a unit price; bargain instead over the cost of a bundle. First

decide how much the consumer would demand if price were set at marginal cost, and then bargain over the price

for this bundle.

Homework problems

Individual problems

Setting a single optimal price: Suppose you have 10 individuals with values {$1, $2, $3, $4, $5, $6, $7, $8, $9, $10}.

Your marginal cost of production is $2.50. What is the profit-maximizing price?

But what about fixed costs?: Using information from question 1, your boss tells you that price cannot drop below $9

because you cannot earn enough profit to cover your fixed cost. What should you tell him?

Different prices to different groups: Using the same demand curve, suppose you find a way to charge one price to the

consumers whose values are {$1, $2, $3, $4, $5}, and a different price to those consumers whose values are {$6, $7,

$8, $9, $10}. If it costs $5 to implement this price-discrimination scheme, should you do it?

Different prices for different quantities: Pretend that the demand curve in question 1 is the demand curve facing a

representative individual, e.g. the individual places a value of $10 on the first item consumed, $9 on the second, and so

on. Suppose that MC=$2.50. If you were going to bundle the goods and set a bundled price, what price would

maximize profits?

Individual Demand: Jennifer loves Czech music. Her favorite composer is Antonin Dvorak who wrote nine

symphonies. Jennifer ranks his 9 symphonies in exactly the order in which they were written. The following data

present the value she places on having these symphonies which she does not currently yet own:

RANK_________Total_Personal_Value

1_______________19

2_______________36

3_______________51

4_______________64

5_______________75

6_______________84

7_______________91

8_______________96

9_______________99

Interpret the above to mean, for example, that Jennifer values her favorite Symphony at $19, and that the total value of

the first Symphony plus Symphony # 2(her second favorite) is $36, etc.

If the symphonies were sold individually on CD's - one symphony per disc - and the price per CD was $10.00, how

many CD?s would she buy?

5

3/9/2016

Page 6

Individual demand & bundling: Referring to the question above: If the symphonies were, also offered as a complete set

of 9 CD's and the price of the entire set was $79.00, would she rather buy the individual CD?s or the box set? HINT:

WHICH OPTION GIVES HER MORE CONSUMER SURPLUS?

Group problems

Pricing decision: Describe a pricing decision in your company. Was price set optimally? How would you improve the

price? What information would you want to improve your price? Be careful to make specific references to long-run

and short-run decision-making. Compute the profit consequences of the decision.

Price Discrimination (different prices to different consumers): Describe a price discrimination opportunity facing your

company. How would you implement the discriminatory pricing practice? How would you identify the different

values that consumers have? How would you prevent arbitrage between the consumers? Compute the profit

consequences of such a discriminatory system.

Price Discrimination (different prices for each unit consumed): Describe a price discrimination opportunity facing your

company. How would you implement the discriminatory pricing practice? How would you identify the different

values that consumers have? Compute the profit consequences of such a discriminatory system.

6

3/9/2016

Page 7

CHAPTER 6: Pricing and elasticity

Between December 20, 1994 and February 1, 1995, the Mexican peso fell by 40 percent against the dollar. Interest

rates in rose sharply, business activity slowed, and unemployment increased dramatically, particularly among those

industries that had paid in dollars for raw materials and debt capital. All of these changes resulted in a dramatic decline

in consumer income and Firm X saw consumption of its processed meats, including hot dogs, decline by 35%. This

was surprising to the company's management because they had thought of their products as staples whose consumption

would hold steady, or perhaps even rise as income fell.

They did a survey and found that many of their customers had turned to a cheaper source of protein---cat food mixed

with eggs and rolled up in a tortilla. Further analysis showed that the decline was limited to Firm X’s premium brands.

The lower-priced brands took off with double-digit volume increases. Unfortunately for Firm X, the lower-end brands

were priced below marginal cost and so lost money.

Firm X would have undoubtedly benefited from a better understanding of demand for its products, and how to set

profitable prices. In this chapter we continue with our analysis of pricing decisions and demand by considering

elasticity, a useful summary statistic of demand.

Defining elasticity

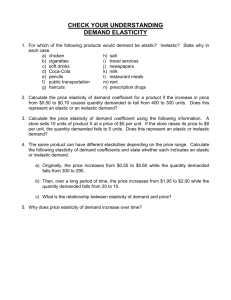

Elasticity describes the sensitivity of demand to changes in various factors. Elasticity is typically the only quantitative

information you will have about demand. Fortunately, it is often enough to make good pricing decisions.

Definition: price elasticity=(% change in quantity demanded) (% change in price)

If |e| is less than one, demand is inelastic.

If |e| is greater than one, demand is elastic.

Price elasticity is negative (because price and quantity move in opposite directions).

Definition: income elasticity=(% change in quantity demanded) (% change in income)

Negative income elasticity means the good is inferior, i.e. as income increases demand declines.

Positive income elasticity means the good is normal, i.e. as income increases demand increases.

Definition: cross-price elasticity=(% change in quantity of good one) (% change in price of good two)

Positive cross price elasticity means the good two is a substitute for good one, i.e. as the price of a substitute increases,

demand increases.

Negative cross price elasticity means the good two is a complement to good one, i.e. as the price of a complement

increases, demand decreases.

Definition: advertising elasticity=(% change in quantity) (% change in advertising)

Advertising elasticity is positive.

Describing demand using price elasticity

Proposition: Price elasticity is negative because price and quantity move in opposite directions, i.e., demand curves

slope downward.

This law reminds us of the fundamental tradeoff: you can raise price and sell less, but earn more on each unit sold; or

you can reduce price and sell more, but earn less on each unit sold. Consumers respond to a price increase by

switching to their next-best alternative. If their next-best alternative is a very close substitute, then demand is very

elastic. A next-best alternative can be a substitute product, or the “no purchase” option.

7

3/9/2016

Page 8

Discussion Question: Do all demand curves slope downward?

Answer: No. Some demand curves may not react at all to price. This is true especially in the short run.

Proposition: In the long-run, demand curves become more price elastic -- |e| increases. If given more time, people

react more to price changes. They are able to find better substitutes when price goes up, and to find more uses for the

good when price goes down.

The second law of demand also could be explained by the speed at which pricing information is disseminated. As time

passes, information about a price change becomes more widely known. A greater number of consumers will have the

information necessary to react to the price change.

Discussion Question: Give an example of the second law of demand.

Answer: In the short-run, the cross-price elasticity of demand for electric water heaters with respect to the price of

electricity is very low. But given enough time, consumers will react to an increase in the price of electricity by

switching to from electric to gas water heaters. The long-run cross-price elasticity of demand for gas water heaters

with respect to the price of electricity is relatively large.

Answer: Another example is ATM fees. Firm X is a bank in a medium-sized mid-western city. In 1997, the bank ran

an experiment to determine elasticity of demand with respect to ATM fees. At a selected number of ATM machines,

user fees were raised from $1.50 to $2.00. When informed of the fee, users typically completed the current transaction,

but avoided the higher-priced ATM machines in the future. In the short-run, elasticity was low. In the long-run, it was

much higher.

Proposition: As price increases, demand curves become more price elastic -- |e| increases. As price goes up,

consumers find previously unattractive substitutes more attractive. As price increases, more and more alternatives

compete with the original good.

Discussion Question: Give an example of the third law of demand.

Answer: High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is a caloric sweetener used in soft drinks that is a perfect substitute for

sugar. Due to U.S. sugar import quotas and price supports, the price of sugar is about twice that of HFCS. Since there

are no close substitutes for the low-priced HFCS, its demand is relatively inelastic. But if the price of HFCS were to

rise to that of sugar, sugar would become a good substitute and the demand for HFCS would become very elastic. In

the figure below, HFCS demand becomes very elastic as the price approaches the price of sugar.

HFCS

Price

Sugar Price

HFCS Demand

HFCS Quantity

Figure 1: HFCS demand

Estimating Elasticity

Note there are several ways to compute percentage changes, depending on whether you use the beginning numbers or

the ending numbers in the denominator. I like to use the midpoint of the prices and quantities in computing percentage

changes, which leads to the following formula.

Definition: Arc price elasticity=[(q1-q2)/(q1+q2)] [(p1-p2)/(p1+p2)]

8

3/9/2016

Page 9

In computing the midpoints, one would use the formulas (q1+q2)/2 and (p1+p2)/2. Since two divides both

denominator and numerator, the formula simplifies, as above.

Discussion Question: Firm X is a small retail supermarket chain with stores located in rural areas of Tennessee,

Kentucky, and Mississippi. In 1999, in one of the stores, the price of all three-liter coke (diet, caffeine-free, and

regular) was decreased from $1.79 to $1.50 in order to match a similar price being offered at Wal-Mart. Quantity of

three-liter coke increased from 210 to 420 units/day, but quantity of two-liter coke declined from 120 to 48 units/day

because the price of two-liter coke stayed constant at $1.19

i.

ii.

iii.

What is the price elasticity of daily demand for three-liter coke at this store?

What is the cross-price elasticity of demand for two-liter coke with respect to the price of three-liter

coke?

What is the price elasticity of daily aggregate demand for coke (two-liter and three-liter)?

Answer:

i.

ii.

iii.

3 Litre

2 Litre

The price elasticity of demand for three-liter coke is [(210-420)/(210+420)] [(1.791.50)/(1.79+1.50)]=-3.87.

Cross price elasticity is [(120-48)/(120+48)] [(1.79-1.50)/(1.79+1.50)]=4.86.

Aggregate demand increases from 870 to 1356 liters of coke. The difficult part about computing

aggregate elasticity is computing the changes in aggregate price. Here we use a price index based on

the initial quantities of two- and three-liter coke.3 The price index drops from $0.52/liter to

$0.46/liter. The aggregate demand elasticity is [(870-1356)/(870+1356)] [(.52-.46)/(.52+.46)]=1.92.

Product

Q 3-liter

P of 3-liter

Initial

210

$1.79

Final % change

420

66.67%

$1.50 -17.63%

Q 2-liter

P of 3-liter

120

$1.79

48

$1.50

-85.71%

-17.63%

4.86

870

$0.52

1356

$0.46

10.92%

-3.12%

-3.50

Total Litres Q liters

P liters

elas.

-3.78

Figure 2: Spreadsheet for computing elasticities

Three-liter coke has a very elastic demand (i), due to the presence of a very close substitute (two-liter coke), as

indicated by its large and positive cross-price elasticity (ii). As the price of three-liter coke falls, consumers substitute

three-liter coke for two-liter coke. The aggregate elasticity is lower (iii), as we would expect because brand loyalty is

much stronger than package loyalty. However, it is not much lower, probably due to the presence of a close substitute,

canned Coke.

Discussion Question: As a grocery store manager, you alternate weekly pickle promotions between Heinz and Vlasic.

On a promotion week for Vlasic, the price of the Vlasic pickles drops by 25 percent and quantity demanded increases

by 300 percent. Compute the price elasticity of demand from this natural experiment.

Answer: Although many students are tempted to mechanically apply the formula to compute 300 percent 25

percent=-12, that would be wrong. Elasticity measures the price sensitivity of demand, holding other factors constant.

Here, the price of Vlasic decreases by 25 percent, but the price of Heinz also increases by 25 percent as it goes “off

promotion.” The change in the Heinz price “pollutes” the natural experiment of reducing the Vlasic price. Also,

consumers could be “stockpiling” their favorite brands, essentially “stealing” consumption from next week when they

do not buy any pickles. Both of these factors will make the weekly price elasticity of demand for Vlasic pickles appear

more elastic than it really is. Failure to recognize this could lead to mistaken pricing decisions.

3

It is important to use a fixed weight price index, one whose weights do not change. Otherwise, you will

overerestimate the degree to which price decreases. This will lead to computed elasticities that are too low.

9

3/9/2016

Page 10

Quick and Dirty Estimators of Price Elasticity

Elasticity of demand can be estimated from survey data, or from naturally occurring experiments like the decline in the

price of 3-litre Coke. However, these data can be costly to collect and may not be precise enough to offer much

practical information. As an alternative to formal estimation, we propose two “quick and dirty” formulas for

computing elasticities.

Linear demand curve elasticity: If you assume that demand can be approximated by a linear function, you can use the

formula, e=p/(p-pmax) to elicit individual price elasticities from consumers. Simply ask what they currently pay for the

product (p) and how high price would have to be for them to stop consuming the product (p max).

Discussion Question: Who recently bought a pair of branded running shoes? What price did you pay? How high

would the price of the brand have to go before you would switch to another brand of running shoes?

Answer: I paid $80 for a pair of Saucony running shoes. At a price of $100, I would switch to another brand such as

Nike. My price elasticity of demand for Saucony brand running shoes is 80/(80-100)=-4. Typically demand for

individual brands is demand is very elastic or sensitive to price, ranging from –1.5 to –4.

Let’s try the same exercise, but at a higher level of aggregation. For example, consider running shoes in general.

Discussion Question: Who recently bought a pair of running shoes? What price did you pay? How high would the

price of all running shoes have to go before you should switch to a different type of shoe?

Answer: I paid $80 for a pair of running shoes. At a price of $280, I would switch to a different type of shoe such as

tennis shoes. My price elasticity of demand for all running shoes is 80/(80-280)=-0.4.

Proposition: Demand for aggregate categories of products is less elastic than demand for the individual brands

comprising the aggregate.

Your elasticity of demand is determined by the attractiveness of your next-best alternative – the opportunity cost of the

purchase. If you next-best alternative is comparable to the one you are making – meaning all you have to do is switch

brands – then your demand is very elastic. But if your next best choice is much less attractive – meaning you have to

switch to a different product altogether – then your demand is relatively inelastic.

Elasticity and market share: The individual brand demand elasticity is approximately equal to the industry elasticity

divided by the brand share.4

Discussion Question: Suppose that the elasticity of demand for all running shoes is –0.4 and the market share of a Nike

running shoe is 20 percent. What is the price elasticity of demand for Nike running shoes?

Answer: The brand elasticity is (–0.4/.20)=-2.0

Using elasticities for prediction

Prediction Formula: (% change in factor)*factor elasticity=(% change in quantity demanded)

Discussion Question: You have an estimate of income elasticity of demand for the Wall St. Journal of 0.50. Between

1997 and 1998, real income grew by 3.5% in the United States. Estimate how this affected demand for the Wall St.

Journal.

Answer: Since the income elasticity of demand is positive, the Wall St. Journal is a “normal” good, i.e. its demand

increases with income. The change in income times the elasticity gives you an estimate of the change in demand,

.5*3.5%=1.75%. Demand for the Wall St. Journal is estimated to increased by 1.75%.

Discussion Question: The 1995 real per-capita median income in Arizona is $30,863; and in Colorado, $40,706. 5

Estimate the difference between per capita consumption of the Wall St. Journal in Colorado and in Arizona?

Answer: The difference in income between Arizona and Colorado is (40,706-30,863)/( 40,706+30,863)/2=27.50%.

The difference in demand is equal to the income elasticity times the difference in income, .5*27.50%=13.75%.

4

The intuition behind this approximation is that an individual brand price change does not have much effect on

industry price.

5

http://www.census.gov/.

10

3/9/2016

Page 11

Demand is estimated to be 13.75% higher in Colorado than in Arizona. Note that these are differences in real, not

nominal, income. Real income is nominal income divided by the price level so that it represents purchasing power.

Using price elasticity to make pricing decisions

Price elasticity and revenue

The reason that price elasticity is such a useful measure of demand is that it is related to the marginal revenue, which

is the marginal benefit of selling another unit. To understand the relationship between marginal revenue and elasticity,

note that %Revenue %Price+ %Quantity.6 When price goes up, quantity goes down, and vice-versa. If the

percentage increase in price is larger than the percentage decrease in quantity, then revenue goes up. This occurs when

demand is relatively inelastic, or relatively unresponsive to price.

We can express the implied relationship between the marginal revenue and elasticity as follows:

Proposition:7 MR=P(1-1/|e|)

It follows that if demand is elastic (|e|>1), then marginal revenue is positive, i.e. you can increase revenue by increasing

quantity. If demand is inelastic (|e|<1), then marginal revenue is negative, i.e. you can increase revenue by decreasing

quantity.

Discussion Question: In 1980, Marion Barry, mayor of the District of Columbia, raised the sales tax on gasoline sold in

the District by 6 percent. What happened to gas tax revenue?

Answer: The increase in the gasoline tax amounts to an increase in price. Quantity declines, but to determine what

happens to revenue, we have to know whether the percentage decline in quantity is larger or smaller than the

percentage increase in price. And this depends on the elasticity of demand for gasoline in the District of Columbia.

Since DC has a lot of commuters who from Virginia and Maryland, it’s gasoline in Maryland and Virginia is a close

substitute for gasoline in the District. In other words, demand for gasoline sold in the District is very elastic. Before the

tax was put into law, gasoline station owners in the District argued against the tax, predicting that it would reduce

quantity by 40 percent. Bill Cook, associate director of the city’s department of finance and revenue predicted that the

tax would raise revenue. He was horribly wrong. The reduction in quantity was 38 percent, very close to what the gas

station owners had predicted. The DC Council repealed the tax within three months. To raise tax revenue, Barry

should have lowered the sales tax instead of raising it.

Note the similarity of the effect of the gas tax to the effect of the turnover tax on the Swedish stock exchange. Demand

for trading on the Swedish stock exchange was very elastic because traders had close substitutes, i.e., trades on the New

York and London exchanges.

Discussion Question: If demand for Nike sneakers is inelastic, should Nike raise or lower price? 8

Answer: If demand is inelastic, you can raise revenue by raising price. You also lower total costs because as you raise

price, you can sell fewer units (fewer units means lower total costs). If total revenue goes up and total costs go down,

then profits increase. It follows that an individual firm should never price on the inelastic portion of its demand curve--always raise price to the point where demand becomes elastic.

Discussion Question: If demand for Nike sneakers is elastic, should Nike raise or lower price? 9

Answer: If demand is elastic, revenue goes up, but so do costs because quantity increases. To determine what to do,

use marginal analysis.

6

This is a first-order approximation and will work well for small changes. The approximation does not work well for

large changes.

7

MR=Revenue/Q=(PQ)/Q=(PQ+QP)/Q=P(1-1/|e|); The symbol “” means "change in."

8

Discussion Question: If demand for Nike sneakers is elastic, should Nike raise or lower price? Answer: It depends

on marginal costs.

9

Discussion Question: If demand for Nike sneakers is elastic, should Nike raise or lower price? Answer: It depends

on marginal costs.

11

3/9/2016

Page 12

Price elasticity and profits

The profit-maximizing or optimal price depends on marginal costs as well as on marginal revenue. From our

discussion of marginal analysis, we know that if MR>MC, then we should lower price and sell more, and if MR<MC,

then we should raise price and sell less. Price is set optimally when MR=MC. We exploit our knowledge of the

relationship between marginal revenue and elasticity to compute a formula for the profit-maximizing price.

Proposition: The profit-maximizing price, i.e. that price where MR=MC, is:

P(1-1/|e|)=MC; or

P=MC/(1-1/|e|); or

(P-MC)/P=1/|e|

Discussion Question: In the Coke example above, the mark-up of 3-liter Coke is 2.7% at a price of $1.50. Should you

raise or lower price?

Answer: In this case the current markup 2.7% is less than the desired markup 1/|3.78|=26% so the current markup is

too low. However, 3-liter Coke is being used as a “loss leader,” and is deliberately priced low as an advertisement to

attract customers in the hope that they will spend money on other items once they come to the store. In this case, you

forego profits by pricing Coke too low in exchange for higher profits on other items.

Discussion Question: Sales people have incentive-compensation schemes based on revenue. Consequently they are

willing to make a sale as long as it increases revenue, i.e., as long as MR>0. The company, for whom the sales people

work, would like to maximize profits, that is make sales as long as MR>MC. This often leads to conflict between the

sales people and their supervisors because the sales people prefer lower prices, those where MR>0, whereas the

company prefers higher prices, those where MR>MC. How should you solve this incentive conflict?

Answer: Sales people make all sales where MR>0 because they are compensated on the basis of revenue. A simple

solution would be to base the incentive-compensation scheme on profitability, rather than on revenue.

Discussion Question: There are five horseracing tracks in Kentucky. The Kentucky legislature allows only one track to

be open at a time. How does this affect the price the track can charge for its product?

Answer: By making sure that there are no close substitutes for the open track, the Kentucky legislature lowers the

elasticity of demand for the track that is open and indirectly permits each track to charge higher prices. Remember (PMC)/P=1/|e|. If the track owners had agreed to this on their own, without the help of the legislation, they would be

violation of the U.S. antitrust laws. This would be a form of collusion to eliminate competition between them. When

they get the Kentucky legislature to do it for them, it is OK because everyone is allowed to petition the government—

even colluders.

Discussion Question: What happened to demand for racetrack betting when a riverboat gambling casino opened up in

the state of Indiana?

Answer: Although the casino’s entrance into the market caused horseracing attendance to fall, the horse-track

gambling profits did not change very much. High-income customers for whom riverboat gambling is a poor substitute

drive horse track profitability. It was the lower-income, lower-profit customers who tended to abandon the racetrack for

riverboat gambling.

Summary of main points

factor elasticity=(% change in quantity demanded) (% change in factor)

Price elasticity, income elasticity, cross-price elasticity, and advertising elasticity measure how sensitive quantity

demanded is to changes in these factors.

Three characteristics of demand can be expressed in terms of price elasticity:

Demand curves are negatively sloped --- e<0.

In the long-run, demand curves become more sensitive to price changes --- |e| increases.

As price increases, demand curves become more sensitive to price changes --- |e| increases.

12

3/9/2016

Page 13

Demand for individual brands is more elastic than demand for aggregate categories of goods.

You can predict changes in demand, (% change in factor)*factor elasticity=(% change in quantity demanded)

Marginal revenue is related to the elasticity of demand, MR=P(1-1/|e|), i.e. if demand is elastic (|e|>1) and you

raise price, revenue decreases. If demand is inelastic (|e|<1) and you raise price up, revenue increases.

You can do marginal analysis with an estimate of elasticity. The following conditions are all equivalent and tell

you when to produce more, or equivalently, reduce price:

MR>MC

P(1-1/|e|)>MC; or

P>MC/(1-1/|e|); or

(P-MC)/P>1/|e|

Homework problems

Individual problems

Marginal Analysis: If elasticity is –2, price is $10 and marginal cost is $8, should you raise or lower price?

Luxury Boxes at Adelphia Coliseum: Among the many design problems that face designers of Adelphia Coliseum is

the number of luxury boxes to include. (Luxury boxes are enclosed suites that look out onto the playing field,

containing plush furniture, bar facilities, and the like) For simplicity, suppose that luxury boxes are sold outright to

local businesses, and that a particular stadium can be built with up to 100 luxury boxes at a cost of construction of

$300K apiece. The designer of this stadium is planning to build 25 boxes, and expects (if he builds 25) to be able to

sell each for $1,000K, for a net profit of 700K X 25= 17,500K. An associate opines that this is crazy—since boxes can

be built at $300K and sold for $1000K apiece, building only 25 leaves money on the table. Is the associate correct?

Why or why not?

Domestic Steel Monopolist: In a small country, a domestic steel monopolist produces and sells steel at $680 per ton,

well above the world price of $375 per ton. This firm is protected against foreign competition by high tariffs that

eliminate competition from foreign firms. The firm maintains the tariffs by contributing heavily to the ruling party. On

the decision of the CEO, the firm has never exported steel. Why export at $375 per ton, when you can sell steel for

$680 per ton domestically? In addition, the average cost of producing steel is never below $400 per ton. Is the CEO

necessarily correct? Can this company make money by exporting steel? Why or why not?

Vandy vs. Tennessee at Adelphia: The Vanderbilt football team is playing Tennessee at Adelphia Coliseum and the

Vanderbilt athletic director is trying to decide how many tickets to sell to both Vanderbilt and Tennessee fans. He can

institute a system of direct price discrimination (different prices to different fans) by selling the tickets through their

different alumni associations. He does not have to worry about arbitrage. Tennessee Fans will purchase as many

tickets as Vanderbilt wants to sell at $10/ticket. For Vanderbilt fans, the athletic director estimates the demand curve in

Table 1. The athletic director decides to sell 50K tickets to Vanderbilt fans because that would imply that the price for

Vanderbilt fans was just equal to the opportunity cost (the foregone opportunity to sell to a Tennessee fan). Is this the

right decision?

Table 1: Vanderbilt Fan Demand for Tickets

Tickets

Price

10K

$18

20K

$16

30K

$14

40K

$12

13

3/9/2016

50K

Page 14

$10

Pricing ATM machines.: Firm X is a bank in a medium-sized mid-western city that currently charges $1/transaction at

its ATM machines. To determine whether to raise price, the bank experimented with two higher prices at selected

ATM machines. The following numbers reflect long-run behavior and are adjusted for seasonality. The marginal cost

of an ATM transaction is $0.50. What price should they charge?

ATM Fee

Usage

$2.00

1000

$1.50

1700

$1.00

2000

Pricing hospital services: Firm X is a private, for-profit hospital in a large southern city. It currently performs about

30 deliveries/month in its obstetrics unit. The price of a delivery is about $5,000 and the marginal cost of a delivery is

about $4,000. The obstetrics unit has the capacity to handle about 50 deliveries/month. The hospital is contemplating

lowering price to attract more patients to run the unit at capacity. What should it do?

Group problems

Elasticity of Demand: Describe the elasticity of demand for one or more of your products and describe how you could

profitably use the information about elasticity. Compute the profit consequences of the advice.

Forecasting Demand: Forecast demand for one of your products. If you used elasticity, how did you estimate it? How

would you profitably use the information contained in the forecast. Compute the profit consequences of the advice.

14