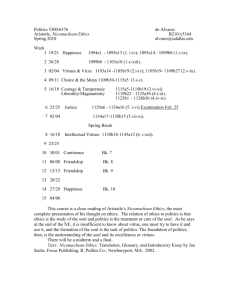

Poststructuralist Approaches to Ethics and Politics

advertisement

Responsibility at the Limit: The Line Between Ethics and Politics Madeleine Fagan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of International Politics Aberystwyth University 30th September 2009 i DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………. (candidate) Date…………………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where *correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………. (candidate) Date…………………………………………………………. [*this refers to the extent to which the text has been corrected by others] STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopyng and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed……………………………………………………….. (candidate) Date…………………………………………………………. i Acknowledgements I have been extremely fortunate in having two fantastic supervisors. Professor Jenny Edkins has provided encouragement, guidance, support and inspiration; I cannot thank her enough for her patience and belief in both me and the thesis. In his position as secondary supervisor Professor Hidemi Suganami has gone far beyond the call of duty, engaging in close and careful reading of my work and providing a constant stream of challenging questions which have improved the clarity and precision of the thesis immeasurably. Most of my friends have had to put up with my absence for far too long—things will get better, I promise! Thanks to Miruna Canagaratnam, Mary Hayman, Parul Rabheru, Anna Solarska, Libby Tregillis and Abigail Wells for reminding me of life outside the thesis and not minding when I go silent for six months at a time. The International Politics Department in Aberystwyth has been a fantastic environment in which to study; friendly, stimulating and intellectually challenging. Thanks in particular to Laura Guillaume, who has kept me sane. I shall be eternally grateful that I have had her to make my way through the last few years with. Thanks also to the Politics department at the University of Exeter where I have found companionship and intellectual stimulation in the latter stages of the thesis. Most of all, my thanks go to my family. They have provided constant and unconditional emotional and financial support, encouragement and belief in me. My thanks for the wake-up calls, the proof-reading, the bibliographic assistance, and for holidays, fun, refuge, and reminding me that there are other things in life—for this in particular I thank James. Finally, without Nick Vaughan-Williams this wouldn’t have happened. He has been unfailingly inspirational, encouraging, engaged, patient and supportive. I cannot thank him enough. I would like to express my gratitude to the ESRC for the research studentship that funded this thesis. ii Summary This thesis engages critically with the question of how poststructuralist notions of ethics and responsibility might inform practical politics. The thesis reviews extant literature in Politics and International Relations which addresses this question and identifies a series of problematic assumptions that underlie these approaches. These tensions are, I argue, a result of a disjuncture between the question asked and the literature drawn upon to answer it. To explore these issues further the thesis then goes back to the work of Emmanuel Levinas, Jacques Derrida and Jean-Luc Nancy which underpins much of the secondary literature, to provide alternative readings of these authors which allow for a different framing of responses to this question. Rather than approaching ethics and politics as originally separable or derivable from one another the thesis argues that the focus needs to shift instead to the relationship between these concepts. The originary ethics drawn from Levinas in order to provide an ethical politics is, I argue, not straightforward. Instead, as the question is traced through this literature the notion of a transcendent Other and the corresponding idea of a pure ethical or responsible relation as a necessary or possible starting point for ethics is challenged. Nancy’s focus on the line or limit refigures the relationship between ethics and politics in such a way that they are only on the line which both separates and joins them. In this alternative reading both immanence and transcendence are corrupted as grounds, so nothing remains to provide answers on the better way to proceed. Ultimately, returning to the original question, this means that there are no grounds—particularly ethical ones—on which to construct a ‘politics of’ anything; only ethical-political decisions on possible answers can be made. iii Contents Preliminaries Declarations…………………………………………………………………………....i Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………ii Summary……………………………………………………………………………...iii Contents……………………………………………………………………………....iv Introduction Ethics in Contemporary Political Life…………………………………………………1 Relativism or Inconsistency: A Double Bind………………………………………….3 Critical Treatments of Ethics and Politics……………………………………………..9 Rethinking Ethics and Politics……………………………………………………….12 Chapter 1 Poststructuralist Approaches to Ethics and Politics Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..22 Poststructuralist Approaches to Ethics and Politics………………………………….24 The Limits of a Poststructuralist Approach? Disrupting Rationality and Prioritising Alterity: Redressing the Balance? A Poststructuralist Ethics? The Move from Ethics to Politics……………………………………………………36 David Campbell: The Politics of Alterity Simon Critchley: The Politics of Ethical Difference Alex Thomson: Democratic Politics iv Questions Raised……………………………………………………………………..73 What Does Ethics Do? The Risk of Abstraction? Favouring Alterity and Multiplicity? Recognition and Cultivation Questioning the Questions Chapter Conclusions………………………………………………………………....89 Chapter 2 Emmanuel Levinas: Responsibility, Politics and the Third Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..92 The Other………………………………………………………………………….…96 The Other as Primary Subjectivity as Responsibility Response and Responsibility The Relation with the Other(s): The Face-to-Face and the Third…………………..117 The Face The Third Problematising (Ir)Responsibility Problematising Ethics and Politics………………………………………………….133 Justice, Charity and the State Ethics and Politics Chapter Conclusions………………………………………………………………..144 v Chapter 3 Jacques Derrida: The (Im)possibility of Responsibility Introduction…………………………………………………………………………148 Decision, Responsibility and Knowledge…………………………………………..150 Subjectivity and the Other Decision Knowledge The Third and the Undecidable……………………………………………………..165 Impossible Responsibility Undecidability The Relation Between Ethics and Politics………………………………………….179 Political Interventions The Conditional and Unconditional: Hospitality and Justice Deducing Ethics from Politics Chapter Conclusions………………………………………………………………..201 Chapter 4 Jean-Luc Nancy: Displacing the Other Introduction…………………………………………………………………………205 Being-With and the Singular Plural………………………………………………...208 Coexistence and the ‘With’ The Singular-Plural Community……………………………………………………………………….…215 Communal Identity and Individuals The In-Common, Communication and Exposure vi Politics and the Political…………………………………………………………….222 Totalisation and the Retreat of the Political ‘Practical’ Politics Ethics and Responsibility…………………………………………………………...233 The Ethical and the Political Relation with no Content Ethics Without Alterity? Separation and the Other Chapter Conclusions………………………………………………………………..248 Chapter 5 Drawing the Line Between Ethics and Politics: Implications for Practical Politics Introduction………………………………………………………………………....253 Levinas, Derrida, Nancy: From Transcendence to Aporia…………………………256 The Original Questions: Looking for a More Responsible Politics………………...259 The Relation Between Ethics and Politics………………………………………….267 Immanence and Transcendence…………………………………………………….274 Relation and Separation Practical Politics…………………………………………………………………….289 Chapter Conclusions………………………………………………………………..300 Conclusion Interrogating the Relationship between Ethics and Politics………………………...304 Limitations and Further Questions………………………………………………….318 Bibliography……….. ……………………………………………………………..323 vii Introduction Ethics in Contemporary Political Life This thesis draws upon a range of critical work in order to investigate and offer possible new approaches to the broad themes of ethics, responsibility and politics. In particular, the thesis is interested in so-called ‘poststructuralist’ approaches to ethics, and how these might inform ‘practical’ politics. The thesis is motivated initially by very concrete, and very common, concerns. How might we relieve suffering? Should we intervene in the affairs of other states? How can we prevent genocide, and how might we best respond to its aftermath? To whom are we responsible? What are our obligations to those inside and outside our state boundaries? In short, what should we do? Answers to these kinds of questions are usually framed in terms of an appeal to ethics, and this is often backed up by some kind of theory of ethics which informs our thinking. Within the discipline of International Relations (IR) this appeal to ethics frames thinking on a whole range of issues, from foreign policy to environmentalism, as well as more obvious ethical concerns such as human rights and torture. Theories of ethics then do a great deal of work in contemporary political life in terms of offering, arguing for and justifying various better ways to proceed. A range of theoretical approaches in IR are used to address ethical issues, from cosmopolitanism and communitarianism to pragmatism, Critical Theory and 8 poststructuralism.1 While most of these theories in a sense lead somewhere, to some vision of a better political organisation, a more ethical way to proceed, a means of judging between ethical claims and so on, poststructuralism has been accused of ‘leading nowhere’. 2 It is this difference, and this critique of poststructuralism, which the thesis investigates. Although ‘poststructuralism’ is a problematic term, I use it to refer to the way that the critics of the approach use the label to group work.3 There is a relative consensus within IR that poststructuralist work does not help with addressing these ethical concerns.4 If poststructuralism has anything to say about ethics, this is not, it is claimed, something which could be used in any practical way to provide answers to pressing ethical questions. In a very broad sense, this thesis examines whether or not this is the case, whether poststructuralist thought does offer any practical guidance for answering ethical questions, whether it can lead to any answers to the question of what we should do. 1 See for example, Daniele Archibugi, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008); David Miller, National Responsibility and Global Justice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Molly Cochran, Normative Theory in International Relations: A Pragmatic Approach (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); Toni Erskine, Embedded Cosmopolitanism: Duties to Strangers and Enemies in a World of ‘Dislocated Communities’ (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations (New York: Basic Books, 1977); Andrew Linklater, Critical Theory and World Politics: Citizenship, Sovereignty and Humanity(London: Routledge, 2007). 2 Chris Brown, International Relations Theory: New Normative Approaches (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 223. 3 Many authors associated with this term would resist being labelled as such and it encompasses a huge range of very different approaches. 4 See for example Brown, International Relations Theory; Chris Brown, ‘Review Article: Theories of International Justice’, British Journal of Political Science 27(2) (1997): 273-297; Chris Brown, ‘“Turtles All the Way Down”: Anti-Foundationalism, Critical Theory and International Relations’, Millennium 23 (1994): 213-236; Molly Cochran, ‘Postmodernism, Ethics and International Political Theory’ Review of International Studies 21 (1995): 237-250; Stephen Krasner, ‘The Accomplishments of International Political Theory’, in Steve Smith, Ken Booth and Marysia Zalewski (eds), International Theory: Positivism and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996; Stephen K. White, 'Poststructuralism and Political Reflection', Political Theory 6(2) (1988): 186-208. 9 In light of this, the thesis is prompted in the first instance by criticisms put to socalled ‘poststructuralist’ approaches which charge it with relativism, inconsistency, or blandness in its treatment of ethics and politics; the argument is that work associated with this approach cannot help us with questions of real-world suffering. In the second instance, it is driven by an element of frustration with the literature which prompts these charges and responds to them. Although a range of seemingly divergent responses are offered, many of these ultimately proceed along a similar path. The problem is often approached, in very broad terms, as one of identifying an ethical starting point and then developing a politics from this.5 However, although faithful to the terms of the question posed by the critics, this seems at odds with the philosophical literature which these ‘poststructuralist’ approaches draw on. This leads it seems to an impossible bind, as noted by the critics: either these approaches offer answers, which seems inconsistent with the philosophical underpinnings of the approach, or they resist doing so, in which case they are charged with relativism. The thesis pursues the question of whether there is a way out of this seeming impasse. Relativism or Inconsistency: A Double Bind The question of how poststructural approaches might inform political action is formulated in a number of ways. In the most general sense, poststructuralist approaches—and deconstructive approaches in particular—are seen as ‘leading nowhere’. What is missing, authors such as Chris Brown contend, is an ability to ‘create theory’.6 In the same vein Stephen White has argued that deconstruction leads 5 See for example David Campbell, National Deconstruction: Violence, Identity and Justice in Bosnia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998) and Simon Critchley, The Ethics of Deconstruction: Derrida and Levinas (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1992). 6 Brown, International Relations Theory, 223. 10 to 'a perpetual withholding operation'.7 In response to the question 'how can poststructuralism inform political reflection?' he argues that the moves of deconstruction are the source of much frustration on the part of someone inquiring about political implications, for it can be interpreted as a strategy for avoiding certain sorts of questions that anyone concerned with politics and political reflection must face. Here is where the suspicion begins to emerge that poststructuralists cannot give coherent answers to such questions.8 As well as these general criticisms regarding giving any answers at all, the specific weakness most often highlighted is the lack of criteria provided by these authors to judge between competing arguments in the fields of normative or ethical claims. For Stephen Krasner, for example, ‘Post-modernism provides no methodology for adjudicating among competing claims … If each society has its own truth … what is the basis for arguing that they are wrong?’9 Although expressions of the general dissatisfaction with approaches labelled as postmodern for not having a research programme, or testable hypotheses, or being able to create theory have become less prevalent, they have been superseded by a more nuanced style of questioning, one which self-consciously claims to have taken on board the way in which these approaches cannot be judged by the same criteria as positivist approaches. While not disregarding the insights of poststructuralism wholesale these sympathetic readings nonetheless find themselves running up against what they see as the limitations in this otherwise potentially interesting body of literature when it comes to judging normative claims. White, 'Poststructuralism’, 191. White, 'Poststructuralism’, 189. 9 Krasner, ‘The Accomplishments of International Political Theory’, 125. 7 8 11 These are the more interesting critiques for the purposes of my discussion because they demonstrate precisely the way in which the questioning of poststructuralism along these lines, however sympathetically approached, cannot produce satisfactory answers. These critiques are not the product of a careless reading but of a very real disjuncture between approaches: poststructuralist approaches are indeed lacking if these are the criteria by which they are judged. This series of questions generally starts with the assumption, explicit or not, that justifications and decisions, particularly of an ethical variety, need to be based on impartial rules. As Brown argues, the problem with poststructuralists is that they are ‘unwilling to think of ethics in terms of the requirements of justice’, where justice is understood in terms of acting in accordance with impartial rules.10 Similarly, Molly Cochran, whilst recognising the political import of a condemnation of existing political orders and practices (as undertaken in this case by Ashley and Walker), makes the argument that ‘clearly, a criterion of judgement, however understated, must be the base of such condemnation.’11 Cochran’s argument however is twofold, firstly a restatement of the assumption that criteria are required for judgement and secondly an argument that Ashley and Walker are in fact sharing this assumption (though they may be unaware of doing so, or attempting to disguise the fact). That is, that their judgements are based on grounds Brown, ‘Theories of International Justice’, 294. See also Brown, ‘“Turtles All the Way Down”’, 225, for a discussion of the need for foundations/justifications. 11 Cochran, ‘Postmodernism’, 246. Ashley and Walker themselves discuss these types of claims in some depth in Richard K. Ashley and R. B. J. Walker, ‘Reading Dissidence/Writing the Discipline: Crisis and the Question of Sovereignty in International Studies’, Special Issue: Speaking the Language of Exile: Dissidence in International Studies, International Studies Quarterly 34(3) (1990), 367-416, 368. See also Marysia Zalewski, ‘All These Theories yet the Bodies Keep Piling up’ in Steve Smith, Ken Booth and Marysia Zalewski (eds), International Theory: Positivism and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996) for a discussion of the problems with this type of questioning and requirements for criteria. 10 12 and criteria and hence their approach is inconsistent.12 Starting from the assumption that criteria are required, it is impossible to conceive of a political or ethical intervention which does not make reference to these criteria in some way. This, the logic runs, where there are political judgements, there must, somewhere in the shadows, be grounds and criteria. Approaches informed by poststructuralism then cannot, if they are to be internally consistent, engage in ethical or political judgement. This is one arm of the pincer movement in which critics would place poststructuralist approaches. The second is the insistence that when these approaches do offer guidance on how to go about making judgements, they do not go far enough. There is ultimately a ‘lack of content’ in any poststructuralist ethics; insufficient guidance on how we might go about ensuring a ‘better global politics’.13 In response to work in this area by Maja Zehfuss, Hannes Stephan makes a similar point in asking how this might help us to answer the question of ‘how to recognise and combat “evil”, as opposed to mere “difference”.’ 14 Similarly, Brown thinks that Campbell’s ethical prescriptions are ‘a little bland’.15 The difficulty in judging competing claims is also addressed by authors who identify themselves as working within a broadly poststructuralist approach. In this case the questioning is of a slightly different form but ultimately points to a similar dissatisfaction. This work engages with this difficulty in order to produce a discussion of the possible ways in which we might be able to differentiate between others and resist violences based on this approach. The desire to be able to differentiate between 12 Cochran, Normative Theory. Cochran, ‘Postmodernism’, 250. See also Cochran, Normative Theory, chapter 4. 14 Hannes R. Stephan, ‘Book Review: Constructivism in International Relations: The Politics of Reality by Maja Zehfuss’, IN-SPIRE (July 2004): 251. 15 Chris Brown, ‘Theories of International Justice’, 295. 13 13 ‘good’ and ‘bad’ others is evident for example in Richard Kearney’s work,16 whilst David Hoy asks how poststructuralism might assist with normative justifications of resistance to domination. He addresses head-on the problem of relativism, as he sees it, through the question ‘why resist?’, that is, why resist this particular form of violence?17 Poststructuralism, he argues, may need ‘supplementing’ if it is to be ethically and politically relevant.18 The interesting thing here is that whilst Hoy acknowledges that the questions he asks are not the poststructuralist questions, he attempts to answer them anyway. Jim George also explicitly poses this question in relation to Levinas, asking ‘how do we choose between competing responsibilities?’.19 It is from this literature that the terms of the question addressed in the thesis are drawn. It is this literature which positions the work of authors such as Ashley, Walker and Campbell as ‘poststructuralist’ and which situates its questioning in the disciplinary context of Politics and IR. The thesis is a response to the research question ‘what are the implications of poststructuralist conceptions of ethico-political responsibility for thinking about practical politics?’ Many of the authors considered in the thesis would hesitate to subscribe to the ‘poststructuralist’ label, and the diversity of the work collected under this banner is huge. One question which I examine in the thesis is whether a ‘poststructuralist’ answer in general can be given or makes sense. Only particular authors and texts can 16 See for example Richard Kearney, Strangers, Gods and Monsters: Interpreting Otherness (London: Routledge, 2003). 17 David Couzens Hoy, Critical Resistance: From Poststructuralism to Post-Critique (Cambridge MA: MIT press, 2004). 18 Hoy, Critical Resistance. 19 Jim George, ‘Realist “Ethics”, International Relations, and Post-modernism: Thinking Beyond the Egoism-Anarchy Thematic’, Millennium 24(2) (1995): 195-223, 211. 14 be considered and those in the selection addressed here have in common a motivation to explicitly answer the questions of applications and practical ethics and politics. This means that the thesis seeks to investigate sources which may not usually be considered ‘poststructuralist’—for example the work of Emmanuel Levinas—as well as work which falls outside the disciplines of Politics and IR. The framing of the thesis in terms of ‘poststructuralist’ approaches is a reference only to the terms of the question posed to authors seen to be working in this tradition. Similarly, the use of ‘practical’ politics is a reference to the particular kinds of answers that this questioning seems to demand. That is, the criticism usually levelled, as discussed above, is that poststructuralist approaches do not tell us what we should do in the practical realm; they may produce theory about politics but this is of little use in answering real world ethical and political questions. This question of ‘practical’ politics is an enduring and seductive one. Particularly with regard to so-called ‘poststructuralist’ accounts, authors are charged by their critics with a demand to make clear what their approach can tell us about this ‘practical’ realm, in terms of both politics and ethics. In trying to demonstrate the substantial ‘practical’ ethical and political significance of a ‘poststructuralist’ argument, I analyse whether the temptation is to provide answers which satisfy these critics, in terms of political or ethical guidance, however minimal. This is, after all, the only way in which a question posed in this way can be addressed on its own terms. The possibility of this tendency in the ‘poststructuralist’ literature provides the second observation which drives the thesis. 15 Critical Treatments of Ethics and Politics What is interesting about approaches such as Cochran’s is that they do flag up an important issue. The problems with inconsistency may be real ones, that is, showing how offering criteria and guidelines is inconsistent with a poststructuralist approach is not an unimportant gesture. But it is not as if Ashley and Walker are unaware of this difficulty. It is here that a key issue emerges: whether we need to go about making judgements, interventions and arguments without recourse to foundational claims or clear criteria (and if so, how), or whether some minimal guidelines might be found to assist in this. The thesis investigates whether, in the literature on which I focus, these minimal grounds can be found. Is Cochran is correct in arguing that an ‘affirmative’ ethics does not fit with ‘postmodern method’, at least as far as the authors I consider?20 Is thinking of ethics in terms of whether it is ‘affirmative’ the only option? The thesis asks whether an ethics of this ‘affirmative’ type can be constructed and what the impact of attempting to do this is. Does a construction of this type limit the scope of an interrogation of the particular construction in political and ethical terms? The issue at stake then may not be that poststructuralist approaches do not go far enough—do not have enough content, are not affirmative enough—but that there may be in some work a tendency to go too far, to try to appease those asking for ‘an ethics’ and to provide it in the terms imposed by the questioners. It is this attempt at answering which then means that the parallel lines of critique, of inconsistency or emptiness outlined above can be introduced. One overall aim of the thesis is to systematically examine the terms of the questions put to poststructuralist approaches, as one possible way out of this impasse. 20 Cochran, ‘Postmodernism’, 250. 16 However, the construction of or perceived need for ethical codes is not only performed by critics of poststructuralism. The reason that this type of questioning needs to be examined in detail is precisely because it also informs poststructuralist contributions. Whilst approaching issues in a very different way from their critics, there is nonetheless enough of a similarity here, at least on some readings, for charges of inconsistency or relativism to gain a foothold. Rather than dismissing these critiques out of hand, it is instructive to examine the conditions for their possibility in more detail. That is, it is useful to address whether, and to what extent, poststructuralist authors do engage with the questions as posed to them in the terms of those questions. In the terms of Cochran’s critique of Ashley, Walker, and Connolly for example the question then becomes whether Cochran misreads what are particular political choices as prescriptions, or whether her highlighting of these prescriptions does demonstrate a tendency by these authors to determine a political programme. The work which opens itself to these charges falls into (at least) two groups. On the one hand, authors such as Jim George offer more specific suggestions; a commitment to a democratic and emancipatory political agenda, an opposition to fascism, a stance of permanent critique. 21 George argues for an ethics, simply put, which insists that there are no ‘good’ reasons why Others in the world should not have the opportunities that I have had for a healthy environment, education, a secure food supply, and the chance for participation in political decision-making. In general, therefore, it is an ethic 21 George, ‘Realist “Ethics”’, 219, 222. 17 which supports political strategies which seek to provide this opportunity and, in general, opposes political strategies which seek to deny it.22 On the other hand, work such as Michael Dillon’s is less straightforward in its suggestions. Underlying these other approaches is a shared assumption that whilst we may not be able to make general prescriptions about the best way to proceed or which political institutions to support and so on, there is nonetheless a need to recognise our way of being as disrupted, shared, and other to itself, and to find ways of welcoming this otherness or alterity. Dillon argues for ‘cultivating an ethos that welcomes rather than denies the human plurality that is integral to its being.’23 It is in this vein that Ashley and Walker also contribute, in calling for an ‘ethics of marginal conduct’; constantly critically working on limits, 24 or an ‘ethics of freedom’. 25 Outside of the disciplines of Politics and IR, Jeffrey Nealon calls for an ethics which affirms alterity, leading to an ‘alterity politics of response’ and Richard Kearney seeks a strategy for distinguishing ‘good’ from ‘bad’ others. 26 Of course, this tendency is not evident across all the work of the various authors mentioned—these are very selective examples intended only to illustrate the difficulty in moving outside the terms of the question. Nor is it evident in all the authors addressing these themes. Jenny Edkins, Véronique Pin-Fat, Nick Vaughan-Williams, and Maja Zehfuss for example offer approaches which steer away from this Jim George, ‘Realist “Ethics”, International Relations, and Post-modernism: Thinking Beyond the Egoism-Anarchy Thematic’, Millennium 24(2) (1995): 195-223, 219. 23 Michael Dillon, ‘Another Justice’, Political Theory 27(2) (1999): 155-175, 162. 24 Ashley and Walker, ‘Reading Dissidence’, 392. 25 Ashley and Walker, ‘Reading Dissidence’, 395. 26 Jeffrey T. Nealon, Alterity Politics: Ethics and Normative Subjectivity (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), 14. See also David Couzens Hoy, Critical Resistance: From Poststructuralism to PostCritique (London: The MIT Press, 2005). 22 18 inclination and in doing so move outside of the bounds of the question.27 However, these are more oblique treatments of the issues which I pursue in the thesis. It is at this point that my analysis starts because, whilst the debates between various approaches on the issue of ethical guidance are of key importance, this is not the primary positioning of the thesis. Rather, the thesis starts at the point of examining the responses given by poststructuralist authors to the questions outlined above, the way in which they have approached the difficulties in negotiating this type of questioning and the insights and limits of their approaches. Rethinking Ethics and Politics I will ask in the thesis whether the temptation to offer answers in the terms of the original question should be resisted. The thesis considers whether the philosophical work which many of these ‘poststructuralist’ arguments draw on provides resources for such an answer and whether, if not, this is a failing or limitation. I explore whether the work of the philosophical authors I consider is lacking in such as way as to require a supplement—that Derrida needs supplementing with Levinas, or Levinas with Derrida,28 for example—or whether the ‘lack’ is where ethical and political possibilities are brought to the forefront. 27 See for example Jenny Edkins, Whose Hunger: Concepts of Famine, Practices of Aid (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000; Véronique Pin-Fat, Universality, Ethics and International Relations: A Grammatical Reading (London: Routledge, forthcoming); Michael J. Shapiro, Cinematic Geopolitics (London: Routledge, 2008); Nick Vaughan-Williams, Border Politics: The Limits of Sovereign Power (Edinburgh; Edinburgh University Press, 2009) and Maja Zehfuss, Wounds of Memory: The Politics of War in Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007). 28 As Critchley and Campbell respectively, argue in Critchley, The Ethics of Deconstruction and Campbell, National Deconstruction. 19 Through exploring this question the thesis aims to offer one possible way out of the debate about ethics thought of in terms of what we should do. It focuses on whether this approach must always ultimately rely on grounds or foundations which may be problematic. The thesis aims to contribute to the undoing of the terms of this type of question and answer, which are, I will argue, what underlie any approach thought of in terms of what ‘ethics’ might offer by way of guidance for ‘practical politics’. What this undoing, through foregrounding the ‘limitations’ of so-called poststructuralist thought introduces is a possibility for making ethical and political claims without generalising, abstracting or needing to rely fully on grounds or foundations. That is, the opening of the possibility for making and convincingly arguing ethical claims outside of the terms of the dominant way of thinking. But the authors I draw on, I will argue, do not provide means to adjudicate between claims, do not, in and of themselves, lead to any particular ethical or political commitments. Nor do they lead to a position which ‘prefers’ the opening, destabilising and welcoming which is often seen to characterise their thought. Rather, they demonstrate that we are always placed (whether this is acknowledged or not) in an unstable position between competing imperatives and that there is no secure way of choosing between these claims. In fact, they demonstrate that insecurity is the very condition of possibility for ethics and politics. Further, these authors do not lead to the position that acknowledging or recognising this positioning is any ‘better’ than not. However, the thesis asks whether it is precisely these ‘limitations’, these refusals to claim that one way is better than another, which allows for this work to be properly ethical and political. If these approaches do not give any answers, does an 20 appreciation of this mean that claims can and must be interrogated as properly political, or ethical, in each instance? Are these modes of interrogation themselves the end or ground—is the question of whether a recognition of our political and ethical situation is the better outcome also a political one?—or are they rather all we are left with? A key concern of the thesis is the exploration of whether stopping at this point is a satisfactory answer or approach, and whether it is possible to go any further. The central question, of the implications of poststructuralist conceptions of ethicopolitical responsibility for thinking about practical politics, relies on a number of presuppositions which I go on to interrogate: the separation between ethics and politics, and a particular understanding of what these realms might comprise, and the separation of theoretical and practical realms. These separations are enabled by particular readings of the philosophical literature whereby the terms on which these separations rely are similarly seen to be in an oppositional and separable relationship, terms such as singular/plural, conditional/unconditional, other/third, immanent/transcendent. Rethinking these relationships through a re-examination of the philosophical literature allows then for a rethinking of the nature of the relationship between ethics and politics. This in turn allows for a different route into thinking about responsibility and ‘practical’ politics. If the philosophical literature on which ‘poststructural’ positions draw has merit then our usual ways of developing answers to pressing ethical and political issues are thrown into question. Thinking in terms of adding poststructural insights to alreadyexisting modes of enquiry does not work, as demonstrated by the charges of relativism and inconsistency. However, these remain important questions that we need 21 to offer answers to and, importantly, that we do offer answers to. As such, new ways of thinking about how to do this and about how we do do this are urgently necessary, and these, it seems, may need to start with an analysis of the terms and mode of enquiry. Whilst some ‘poststructuralist’ work does address this question of what poststructuralist notions of ethics might have to say about practical politics, one hypothesis is that the terms in which it is posed mean that no answer which draws on poststructuralist approaches will ever be satisfactory, either in the terms in which the question is posed, or in terms of fidelity to the philosophical literature which is drawn on. In the face of questioning of this type, so-called poststructuralist approaches are placed in an impossible bind: either the answers given are seen as weak and relativist, or they are seen as internally contradictory. There is a sense in which I am sympathetic to these criticisms. Answers of the type desired by the critics necessarily fall, I will argue, into one of these camps. However, the question remains whether this is a failing of the question itself, and the temptation to answer it, rather than of the poststructuralist approach. In order to investigate more fully what existing literature offers in response to the question of poststructuralism, ethics and politics, I draw initially on the work of David Campbell, Simon Critchley and William Connolly. These authors all attempt to set out, from a ‘poststructuralist’ perspective, an answer to what an ethical politics might look like. Although a great deal of other work touches on these issues, these are particularly detailed and systematic approaches. They also all draw on the work of Jacques Derrida, whose deconstructive approach is frequently cited, as above, when 22 arguing that ‘poststructuralist’ approaches do not help us with ethical and political questions. The thesis then actually addresses a rather more limited question than that posed by the critics of ‘poststructuralism’, but this in itself is part of the answer. This also means that there are many other possible answers, drawing on other collections of literature which might be, and have been, formulated. The literature I focus on in Chapter 1 then is work which attempts to answer the question of the application of poststructuralist ethics to politics, and which deals explicitly with this theme. Although the field here is relatively broad, as suggested above, much of the work draws on the thought of Emmanuel Levinas and Jacques Derrida and so it is the authors who develop this thought that I focus on, in particular Campbell, Critchley and Connolly. In engaging with the work of these authors I investigate whether there is a tendency towards providing grounds or prescriptions, albeit very minimal and of a rather different kind from those usually posited. I ask whether in this literature there is a desire to provide an account of a ‘poststructuralist’ ethics, which can be used to inform politics and a corresponding political goal. This analysis raises the question of whether the positions articulated are necessary outcomes of the philosophical literature that is drawn on, whether they are supported by this literature, and whether they represent the only possible reading of it. Do Levinas and Derrida provide resources for answering the question that the authors in Chapter 1 draw on them to do? If the charges of inconsistency, relativism or blandness can be made, is this a valid critique of either authors such as Campbell, Critchley and Connolly, or of the positions they draw on? To what extent does the question which Levinas and Derrida are drawn upon to answer determine the reading 23 of their work which is adopted? In order to investigate this I turn back to the philosophical literature. Chapter 2 focuses on the work of Emmanuel Levinas, who often provides the ethical starting point for the approaches discussed in Chapter 1. I ask whether this starting point is as clear-cut as it initially seems, whether Levinas does provide resources from which either ethical or political positions can be developed. The chapter presents a reading of his work where the figure of the Third is foregrounded. The chapter asks whether a reliance on a particular reading of Levinas in which the Third is not taken seriously enough leads to the attempt to provide an ethics which can then be used to inform politics. Does Levinas provide an unproblematic ethical starting point, as he is often taken as doing? Are ethics and politics separable in Levinas’s work in such a way that one can inform the other? The adoption of Levinas as a resource for the thinkers discussed in Chapter 1 is in many ways due to the use of his thought by Jacques Derrida. This chapter investigates whether Levinas can provide the ethical backbone of a deconstructive approach as he is often taken to do (for example by the authors considered in Chapter 1). Chapter 3 then moves on to consider Derrida’s work and investigate whether Derrida provides resources lacking in Levinas for formulating an ethical politics. With a more explicit focus on the difficulties internal to concepts such as ethics and responsibility, Derrida’s work highlights more clearly the problems in constructing an ethics. Overall, these chapters ask whether it is possible to read the work of Levinas and Derrida as rather more complementary than is often the case. Is the approach 24 whereby one provides resources to ‘fill in the gaps’ in the other’s work supported, and are there alternative ways of looking at their relationship? Derrida’s work focuses in more detail on the nature of the relation between ethics and politics and raises the question of the relation between them and of the possibility of ethics and responsibility. This chapter analyses Derrida’s use of ethics and politics and their relationship to the realms of the conditional and unconditional, right and law and so on. I ask whether these realms are separable and whether the concepts of ethics and politics are aligned with one or the other. Derrida’s work also introduces the themes of aporia and hiatus which raises the question of how we might be able to think about the concepts of ethics and politics with this in mind. How are ethics and politics connected or separated? How might they be separated or contain a gap within themselves? Is this gap or limit a problem to be overcome? In order to examine the notion of this gap, line or limit further, Chapter 4 turns to the work of Jean-Luc Nancy. Nancy provides a resource rarely used in the literature on ethics and politics in IR and Politics which I focus on here, but one which is useful in thinking about how the concepts of ethics and politics are related. Both Levinas and Derrida retain a commitment, even if only as a starting point for demonstrating their interpenetration, to thinking ethics and politics in opposition. Nancy, on the other hand, shifts the terms of the debate somewhat, in focusing instead on the line or limit as such as the starting point. Nancy’s ontology of being-with thus provides one alternative way of approaching questions of ethics and politics which allows for a move outside the framing of the debate in terms of how ethics might inform politics. 25 Whilst Levinas and Derrida both bring into question whether we need something from ‘outside’ to provide ethical impetus, to interrupt the ‘totalising’ realm of politics, and whether there is any place from which to derive original principles, Nancy gives this questioning a place at the centre of his project. The chapter explores his concept of transimmanence as a potential way of reconceptualising the nature of and relation between ethics and politics which means that we do not need to look to an outside for ethics, or rather which disrupts the terms of the question that places immanence and transcendence in opposition in this way. Nancy provides a possible way out of oppositional thinking with implications for how we think about ethics and politics, responsibility and the importance of the line or limit not as limitation but as site of possibility. Having brought into focus the questioning of the line between ethics and politics, Chapter 5 then investigates the implications of this for the original research question. The chapter asks whether we need to appeal to an ‘outside’ to provide ethics or an ethical disruption, and whether there are grounds on which we can know if this disruption is the better way to proceed. Can ethics solve the questions of politics? Can a ‘politics of’ anything be derived from it? Whilst the authors considered for example in Chapter 1 attempt to get away from the problem of providing programmes for politics by recourse to politics in terms of practices I ask whether this attempt is successful. Can or must we consider ethics and politics as the same types of things? What are the implications of doing this? Is it possible to move away from the notion of ethics as answerable and decidable and if so what does this mean for politics? 26 This final chapter investigates what the implications are of an approach which refuses an answer to the problem of ethics. It asks whether ultimately this leads back to relativism and a disengagement from political decisions. The chapter also looks into the question of whether a recognition of the difficulties inherent in ethical and political decisions should be promoted; whether it is better to acknowledge or uncover the unstable grounds on which we operate. It seems very difficult to break away from a notion of ethics as decidable, and so a corresponding notion of politics as answerable is always present. In this instance, politics slips back into being answerable rather than a question of practices. Reemphasising ‘practical’ politics goes some way towards resisting the temptation to theorise political answers but this move can only be made once the relationship between ethics and politics and the nature of these concepts in the first place has been re-examined. However, and perhaps more importantly, what emerges is that the decision to recognise or cover over the difficulties in providing programmes or theories are ultimately ethical and political ones. The thesis does not provide grounds for arguing that this uncovering, or politicisation, is the better way to proceed. The philosophical literature drawn on, it will be argued, provides no guidance. This leads to neither relativism nor inconsistency but to unlimited ethical and political decisions and interventions, whether recognised as such or not, for which, in the absence of grounds we, as singular-plural, are always responsible. Of course, this lack of ground casts the analysis offered in the thesis too in terms of an ethical and political intervention. This too undertakes the task of theorising and making general claims 27 about the nature of politics, but one key point is that we cannot get away from this; it is all we can, and do, do. 28 The student has requested that this electronic version of the thesis does not include the main body of the work - i.e. the chapters and conclusion. The other sections of the thesis are available as a research resource. 29 Bibliography Agamben, Giorgio, Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999). Archibugi, Daniele, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008). Ashley, Richard K., ‘Living on Border Lines: Man, Poststructuralism, and War’ in James Der Derian and Michael J. Shapiro (eds), International/Intertextual Relations: Postmodern Readings of World Politics (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1989). Ashley, Richard, K. and R. B. J. Walker, ‘Reading Dissidence/Writing the Discipline: Crisis and the Question of Sovereignty in International Studies’, Special Issue: Speaking the Language of Exile: Dissidence in International Studies, Internaional Studeis Quarterly 34(3) (1990), 367-416. Bauman, Zygmunt, Postmodern Ethics, (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993). --------, Modernity and the Holocaust (London: Polity, 2001). 30 Beardsworth, Richard, ‘The Future of Critical Philosophy and World Politics’ in Madeleine Fagan, Ludovic Glorieux, Indira Hasimbegovic and Marie Suetsugu (eds), Derrida: Negotiating the Legacy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007): 45-66. Bennett, Jane and Michael Shapiro, The Politics of Moralizing (London: Routledge, 2002). Bergo, Bettina, Levinas Between Ethics and Politics: For the Beauty that Adorns the Earth (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1999). Bernasconi, Robert, ‘The Crisis of Critique and the Awakening of Politicisation in Levinas and Derrida’ in Martin McQuillan (ed.), The Politics of Deconstruction: Jacques Derrida and the Other of Philosophy (London: Pluto Press, 2007). Brown, Chris, International Relations Theory: New Normative Approaches (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992). -------- ‘ “Turtles All the Way Down”: Anti-Foundationalism, Critical Theory and International Relations’, Millennium 23 (1994): 213-236. Bulley, Dan, ‘Negotiating Ethics: Campbell, Ontopology and Hospitality’, Review of International Studies 32 (2006): 645-663. 31 Butler, Judith, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004). Campbell, David, Politics Without Principle: Sovereignty, Ethics, and the Narratives of the Gulf War (London: Lynne Rienner, 1993). --------, ‘The Deterritorialization of Responsibility: Levinas, Derrida, and Ethics After the End of Philosophy’ Alternatives 19 (1994): 455-484. --------, ‘The Possibility of Radical Interdependence: A Rejoinder to Daniel Warner’ Millennium 25 (1) (1996): 129-141. --------, National Deconstruction: Violence, Identity and Justice in Bosnia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998). --------, Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998). --------, ‘Why Fight: Humanitarianism, principles and post-structuralism’, Millennium 27(3) (1998): 497-521. --------, ‘Beyond Choice: The Onto-Politics of Critique’, International Relations 19(1) (2005): 127-134. --------, ‘Roundtable Discussion’, Millennium 34(1) (2005): 237-258. 32 Campbell, David and Michael Dillon, ‘Postface: The Political and the Ethical’, in Campbell and Dillon (eds), The Political Subject of Violence (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993): 161-179. Campbell, David and Michael Dillon (eds), The Political Subject of Violence (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993). Campbell, David and Michael J. Shapiro, ‘Introduction: From Ethical Theory to the Ethical Relation’ in Campbell and Shapiro (eds), Moral Spaces: Rethinking Ethics and World Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999). Campbell, David and Michael J. Shapiro (eds), Moral Spaces: Rethinking Ethics and World Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999). Caputo, John, Against Ethics: Contributions to a Poetics of Obligation with Constant Reference to Deconstruction (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993). Caputo, John (ed.), Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida (New York: Fordham University Press, 1997). Cochran, Molly, ‘Postmodernism, Ethics and International Political Theory’ Review of International Studies 21 (1995): 237-250. 33 --------, Normative Theory in International Relations: A Pragmatic Approach (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). Cohen, Richard (ed.), Face to Face with Levinas (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986). Connolly, William E., ‘Identity and Difference in Global Politics’ in James Der Derian and Michael J. Shapiro (eds), International/Intertextual Relations: Postmodern Readings of World Politics (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1989). --------, Identity\Difference: Democratic Negotiations of Political Paradox (London: Cornell University Press, 1991). --------, The Ethos of Pluralization (London: University of Minnesota Press, 1995). --------, ‘Suffering, Justice and the Politics of Becoming’, in David Campbell and Michael Shapiro (eds), Moral Spaces: Rethinking Ethics and World Politics (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 1999): 125-154. --------, ‘Immanence, Abundance, Democracy’, in Lars Tonder and Lasse Thomassen (eds), Radical Democracy: Politics Between Abundance and Lack (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005). Couzens Hoy, David, Critical Resistance: From Poststructuralism to Post-Critique (Cambridge MA: MIT press, 2004). 34 Coward, Martin, ‘Editor’s Introduction’, Journal for Cultural Research, special issue on Jean-Luc Nancy, 9(4) (2005): 323-329. Critchley, Simon, ‘Re-tracing the Political: Politics and Community in the Work of Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy’ in David Campbell and Michael Dillon (eds), The Political Subject of Violence (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993). --------, The Ethics of Deconstruction: Derrida and Levinas (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1992). --------, Ethics, Politics, Subjectivity: Essays on Derrida, Levinas and Contemporary French Thought (London: Verso, 1999). --------, ‘Five Problems in Levinas’s View of Politics and the Sketch of a Solution to them’, Political Theory 32(2) (2004): 172-185. --------, Infinitely Demanding: Ethics of Commitment, Politics of Resistance (London: Verso, 2007). Dauphinee, Elizabeth, Finding the Other in Time: On Ethics, Responsibility and Representation, Doctoral Thesis. (Toronto: York University, 2005). Deleuze, Gilles, Pure Immanence: Essays on a Life (New York: Zone Books, 2005). 35 Der Derian, James, ‘Post-Theory: The Eternal Return of Ethics in International Relations’ in Michael W. Doyle and G. John Ikenberry (eds), New Thinking in International Relations Theory (Boulder: Westview Press, 1997). Der Derian, James and Michael J. Shapiro (eds), International/Intertextual Realtions: Postmodern Readings of World Politics (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1989). Derrida, Jacques, Writing and Difference (London: Routledge, 1978). --------, ‘Some Statements and Truisms about Neologisms, Newisms, Postisms, Parasitisms, and Other Small Seismisms’, in D. Carroll (ed.), The States of ‘Theory’: History, Art, and Critical Discourse (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990). --------, ‘ “Eating well” or the Calculation of the Subject: An Interview with Jacques Derrida’, in Eduardo Cadava, Peter Connor and Jean-Luc Nancy (eds.), Who Comes After the Subject (London: Routledge, 1991). --------, ‘Force of Law’, in Drucilla Cornell, Michel Rosenfield and David Gray Carlson (eds), Deconstruction and the Possibility of Justice (London: Routledge, 1992). 36 --------, The Other Heading: Reflections on Today’s Europe, translated by PascaleAnne Brault and Michael B. Naas (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992). --------, The Gift of Death, translated by David Wills (London: University of Chicago Press, 1995). --------, ‘Remarks on Deconstruction and Pragmatism’ in Chantal Mouffe (ed.), Simon Critchley, Jacques Derrida, Ernesto Laclau and Richard Rorty: Deconstruction and Pragmatism (London: Routledge, 1996). --------, ‘Villanova Roundtable’ in John D. Caputo (ed.), Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida (New York: Fordham University Press, 1997). --------, ‘On Responsibility: Interview with Jonathan Dronsfield, Nick Midgley, Adrian Wilding’ [1993], in Jonathan Dronsfield and Nick Midgley (eds), ‘Responsibilities of Deconstruction’ Special issue of PLI: Warwick Journal of Philosophy 6 (1997): 19-35. --------, ‘Perhaps or Maybe’, in Jonathan Dronsfield and Nick Midgley (eds), ‘Responsibilities of Deconstruction’ Special issue of PLI: Warwick Journal of Philosophy 6 (1997): 1-18. 37 --------, ‘Politics and Friendship: A Discussion with Jacques Derrida’, Centre for Modern French Thought, University of Sussex 1st December 1997. http://www.sussex.ac.uk/Units/frenchthought/derrida.htm, accessed 07/10/2006. --------, ‘Hospitality, Justice and Responsibility: A Dialogue with Jacques Derrida’, in Richard Kearney and Mark Dooley (eds), Questioning Ethics: Contemporary Debates in Philosophy (London: Routledge, 1999). --------, Adieu: To Emmanuel Levinas, trans. Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999). --------, Deconstruction Engaged: The Sydney Seminars, ed. Paul Patton and Terry Smith (Sydney: Power Publications, 2001). --------, On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness, trans. Mark Dooley and Michael Hughes (London: Routledge, 2001). --------, ‘Autoimmunity: Real and Symbolic Suicides – A Dialogue with Jacques Derrida’ in Giovanna Borradori (ed.), Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jurgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida (London: University of Chicago Press, 2003). --------, Paper Machine (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005). 38 --------, The Politics of Friendship [1994], trans. Gorge Collins (London: Verso, 2005). --------, Rogues: Two Essays on Reason (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005). Derrida, Jacques and Bernard Stiegler, Echographies of Television (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002). Dillon, Michael, Politics of Security: Towards a Political Philosophy of Continental Thought (London: Routledge, 1996). --------, ‘Another Justice’ Political Theory 27(2) (1999): 155-175. Dooley, Mark, ‘The Civic Religion of Social Hope: A Reply to Simon Critchley’, Philosophy and Social Criticism 27(5) (2001): 35–58. Edkins, Jenny, Poststructuralism and International Relations: Bringing the Political Back in (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1999). --------, ‘Ethics and Practices of Engagement: Intellectuals as Experts’, International Relations 19(1) (2005): 64-69. --------, ‘Exposed Singularity’, Journal for Cultural Research 9(4) (2005): 359-386. 39 --------, ‘What it is to be Many: Subjecthood, Responsibility and Sacrifice in Derrida and Nancy’, in M. Fagan et al (eds), Derrida: Negotiating the Legacy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007). --------, Whose Hunger: Concepts of Famine, Practices of Aid (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000). Erskine, Toni, Embedded Cosmopolitanism: Duties to Strangers and Enemies in a World of ‘Dislocated Communities’ (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). Franke, Mark F. N., ‘Refusing an Ethical Approach to World Politics in Favour of Political Ethics’ European Journal of International Relations 6(3) (2000): 307333. George, Jim, ‘Realist “Ethics”, International Relations, and Post-modernism: Thinking Beyond the Egoism-Anarchy Thematic’, Millennium 24(2) (1995): 195-223. George, Larry, ‘Pharmacotic War and the Ethical Dilemmas of Engagement’, International Relations 19(1) (2005): 115-125. Grossman,Vasily, Life and Fate, Trans. R. Chandler (Vintage: London, 2006 [1980]). Hagglund, Martin, ‘The Necessity of Discrimination: Disjoining Derrida and Levinas’ Diacritics 34(1) (2004): 40-71. 40 Hatley, James, Suffering Witness: the Quandary of Responsibility after the Irreparable (New York: State University of New York Press, 2000). Howells, Christina, Derrida: Deconstruction from Phenomenology to Ethics (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999). Hutchens, B. C., Jean-Luc Nancy and the Future of Philosophy (Durham: Acumen Publishing, 2005). Hutchings, Kimberley, ‘The Possibility of Judgement: moralizing and theorizing in International Relations’, Review of International Studies 18 (1992): 51-62. James, Ian, ‘On Interrupted Myth’, Journal of Cultural Research 9(4) (2005): 331349. James, Ian, The Fragmentary Demand: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Jean-Luc Nancy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006). Kearney, Richard, Strangers, Gods and Monsters: Interpreting Otherness (London: Routledge, 2003). Keenan, Thomas, Fables of Responsibility: Aberrations and Predicaments in Ethics and Politics (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1997). 41 Krasner, Stephen, ‘The Accomplishments of International Political Theory’, in Steve Brown, Chris, ‘Review Article: Theories of International Justice’, British Journal of Political Science 27(2) (1997): 273-297. Lacoue-Labarthe, Phillipe and Jean-Luc Nancy, Retreating the Political (London: Routledge, 1997). Levinas, Emmanuel, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, Trans. A. Lingis (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 2005 [1961]). --------, ‘Transcendence and Height’ (1962), in Adriaan Peperzak, Simon Critchley and Robert Bernasconi (eds), Emmanuel Levinas: Basic Philosophical Writings (Indiananapolis: Indiana University Press, 1996). --------, ‘Substitution’ (1968), in Adriaan Peperzak, Simon Critchley and Robert Bernasconi, Robert (eds), Emmanuel Levinas: Basic Philosophical Writings (Indiananapolis: Indiana University Press, 1996): 79-97. --------, Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 2004 [1981]). --------, ‘Peace and Proximity’ (1984), in Adriaan Peperzak, Simon Critchley and Robert Bernasconi, Robert (eds), Emmanuel Levinas: Basic Philosophical Writings (Indiananapolis: Indiana University Press, 1996): 161-171. 42 --------, Ethics and Infinity: Conversations with Phillipe Nemo, Trans. R. Cohen (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1985). --------, ‘Interview with Francois Poire’ (1986) in Jill Robbins (ed.), Is it Righteous to Be: Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). --------, ‘The Vocation of the Other’ (1988) in Jill Robbins (ed.), Is it Righteous to Be: Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). --------, ‘Being-for-the-other’ (1989) in Jill Robbins (ed.), Is it Righteous to Be: Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). --------, ‘Interview with Solomon Malka’ in Jill Robbins (ed.), Is it Righteous to Be: Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). --------, ‘Responsibility and Substitution’ in Jill Robbins (ed.), Is it Righteous to Be: Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). --------, ‘The Proximity of the Other’ in Jill Robbins (ed.), Is it Righteous to Be: Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). --------, ‘Philosophy, Justice and Love’, Jill Robbins (ed.), Is it Righteous to Be: Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). 43 Levinas, Emmanuel and Richard Kearney, ‘Dialogue with Emmanuel Levinas’ in Richard Cohen (ed.), Face to Face with Levinas (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986). Librett, Jeffrey, ‘Foreward’ to Jean-Luc Nancy, The Sense of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997). Linklater, Andrew, Critical Theory and World Politics: Citizenship, Sovereignty and Humanity (London: Routledge, 2007). May, Todd, Reconsidering Difference: Nancy, Derrida, Levinas and Deleuze (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania University Press, 1997). Miller, David, National Responsibility and Global Justice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). Mouffe, Chantal (ed.), Simon Critchley, Jacques Derrida, Ernesto Laclau and Richard Rorty: Deconstruction and Pragmatism (London: Routledge, 1996). Nancy, Jean-Luc, The Inoperative Community (London: University of Minnesota Press, 1991). --------, ‘Of Being-in-Common’ in Miami Theory Collective (ed.), Community at Loose Ends (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991). 44 --------, The Birth to Presence (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993). --------, The Sense of the World (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1997). --------, Being Singular Plural (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000). --------, A Finite Thinking (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003). --------, The Ground of the Image (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005). --------, ‘The Insufficiency of “Values” and the Necessity of “Sense”’, Journal for Cultural Research 9(4) (2005): 437-441. --------, The Creation of the World or Globalization (Albany: The State University of New York Press, 2007). --------, Listening (New York: Fordham University Press: 2007). --------, Philosophical Chronicles, trans. Franson Manjali (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008). Nealon, Jeffrey T., Alterity Politics: Ethics and Performative Subjectivity (London: Duke University Press, 1998). 45 Norris, Andrew, ‘Jean-Luc Nancy and the Myth of the Common’, Constellations 7(2) (2000): 272-295. Odysseos, Louiza, ‘Dangerous Ontologies: The Ethos of Survival and Ethical Theorizing in International Relations’ Review of International Studies 28 (2002): 403-418. --------, ‘On the Way to Global Ethics? Cosmopolitanism, ‘Ethical’ Selfhood and Otherness’, European Journal of Political Theory 2(2) (2003): 183-207. Patrick, Morag, Derrida, Responsibility and Politics (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997). Peperzak, Adriaan, Simon Critchley and Robert Bernasconi (eds), Emmanuel Levinas: Basic Philosophical Writings (Indiananapolis: Indiana University Press, 1996). Perpich, Diane, ‘A Singular Justice: Ethics and Politics Between Levinas and Derrida’, Philosophy Today 42 (1998): 59-71. Pin-Fat, Véronique, Universality, Ethics and International Relations: A Grammatical Reading (London: Routledge, forthcoming). Plant, Bob, ‘Doing Justice to the Derrida-Levinas Connection: A Response to Mark Dooley’, Philosophy and Social Criticism 29(4) (2003): 427-450. 46 Prozorov, Sergei, ‘X/Xs: Toward a General Theory of the Exception’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 30(1) (2005): 81-112. Robbins, Jill (ed.), Is it Righteous to be: Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). Shapiro, Michael J., Cinematic Geopolitics (London: Routledge, 2008). --------, ‘The Ethics of Encounter: Unreading, Unmapping the Imperium’ in David Campbell and Michael J. Shapiro (eds), Moral Spaces: Rethinking Ethics and World Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999). Simmons, William, ‘The Third: Levinas’ Theoretical Move from An-archical Ethics to the Realm of Justice and Politics’, Journal of Philosophy and Social Criticism 25 (1999): 83-10. Smith, Daniel, ‘Deleuze and Derrida, Immanence ad Transcendence: Two Directions in Recent French Thought’ in Paul Patton and John Protevi (eds), Between Deleuze and Derrida (London: Continuum, 2003). Smith, Jason, ‘Introduction: Nancy’s Hegel, The State and Us’, in Jean-Luc Nancy, Hegel: the Restlessness of the Negative (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002). 47 Smith, Steve, Ken Booth and Marysia Zalewski (eds), International Theory: Positivism and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). Stephan, Hannes R., ‘Book Review: Constructivism in International Relations: The Politics of Reality by Maja Zehfuss’, IN-SPIRE (July 2004). Thomson, Alex, Deconstruction and Democracy: Derrida’s Politics of Friendship (London: Continuum, 2005). Vaughan-Williams, Nick, ‘Beyond a Cosmopolitan Ideal: The Politics of Singularity’, International Politics 44(1) (2007): 107-124. --------, Border Politics: The Limits of Sovereign Power (Edinburgh; Edinburgh University Press, 2009). Walker, R.B.J, Inside/Outside: International Relations as Political Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). Walzer, Michael, Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations (New York: Basic Books, 1977). Warner, Daniel, An Ethic of Responsibility in International Relations (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1991). 48 Watkin, Christopher, ‘A Different Alterity: Jean-Luc Nancy’s “Singular Plural”’, Paragraph 30(2) (2007): 50-64. White, Stephen, K., 'Poststructuralism and Political Reflection', Political Theory 6(2) (1988): 186-208. Williams, Caroline, Contemporary French Philosophy: Modernity and the Persistence of the Subject (London: Athlone Press, 2001). Zalewski, Marysia, ‘All These Theories yet the Bodies Keep Piling up’ in Steve Smith, Ken Booth and Marysia Zalewski (eds), International Theory: Positivism and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). Zehfuss, Maja, ‘Remembering to Forgive: The “War on Terror” in a Dialogue Between German and US Intellectuals’ International Relations 19(1) (2005): 91102. --------, Wounds of Memory: The Politics of War in Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007). 49