1 introduction

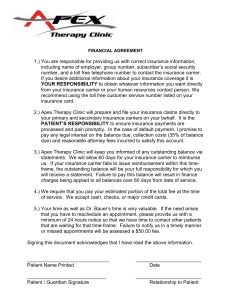

advertisement