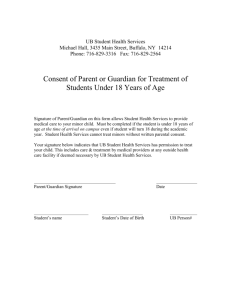

Now You're the Guardian - Public Guardian

advertisement