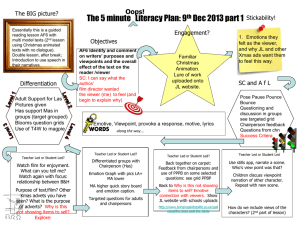

Engaging young peopleand children in edLiterature

advertisement