Advanced Materials_21_10-11_2009 - Spiral

advertisement

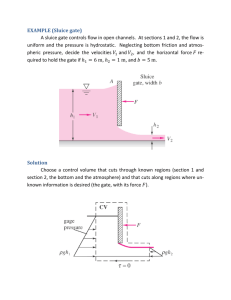

Submitted to DOI: 10.1002/adma.((200801725)) High Performance Polymer-Small Molecule Blend Organic Transistors** R. Hamilton1*, J. Smith2, S. Ogier3, M. Heeney4, J. E. Anthony5, I. McCulloch1, J. Veres6, D. D. C. Bradley2, T. D. Anthopoulos2 [*] Departments of Chemistry1 and Physics2, Imperial College London, South Kensington, SW7 2AZ, (United Kingdom) E-mail: R.Hamilton@Imperial.ac.uk; Thomas.Anthopoulis@Imperial.ac.uk UKPETeC3, NETPark, Sedgefield, County Durham TS21 3FD, (United Kingdom) Department of Materials4 , Queen Mary, University of London, Mile End Road, E1 4NS, (United Kingdom) Department of Chemistry5, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506-0055, (U.S.A.) Eastman Kodak6, 1999 Lake Avenue, Rochester, NY 146500, (U.S.A.) We are grateful to the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and Research Councils UK (RCUK) for financial support. TDA is an EPSRC Advanced Fellow and an RCUK Fellow/Lecturer. Keywords: TIPS, F-ADT, Organic Semiconductors, Organic Transistors, OFETs Abstract. Solution processable organic semiconductors have shown significant improvement over recent years, and are now poised for mainstream commercialisation. Although the electrical performance of the best devices are now in excess of the first generation application requirements, increasing complexity will demand improved semiconductor charge carrier mobilities. Functionalised oligoacenes have demonstrated both solution processability and high charge carrier mobility, however small molecules may demonstrate limitations in fabrication compatibility with printing techniques. Here we show that a blended formulation of semiconducting small molecule and a polymer matrix can provide high electrical performance within thin film field effect transistors (OTFTs), demonstrating charge carrier mobilities of greater than 2 cm2V-1s-1, good device to device uniformity and the potential to fabricate devices from routine printing techniques. 1 Submitted to Main Text Solution-deposited, robust alternatives to amorphous silicon have been pursued commercially for over a decade.[1-3] Introduction of an economically viable technology that enables large area flexible displays[4, 5] as well as ubiquitous cheap electronics such as radio frequency identification tags[6, 7] is expected to be highly disruptive to the silicon dominated market.[8, 9] Solution-deposited small molecules[10-14] and polymers[15-17] are viable approaches that promise to meet the challenge. To date, small molecules have provided the highest headline field effect mobilities,[18, 19] but device-to-device variation due to morphology issues makes large area deposition via printing difficult,[20, 21] while high solubility makes finding orthogonal solvents for further solution processing a considerable constraint. Polymers however, demonstrate excellent device uniformity[22] and solution rheology, which makes them ideal for large area printing,[5] but have not yet demonstrated the high mobility to make them truly useful in commercial devices.[23] Combining the high mobility of crystalline small molecules with the device uniformity of polymers is very attractive and has been approached in a number of ways. These include increasing the crystallinity of a polymer such as p3HT[16] by introducing rigid units into the polymer back-bone and creating regiosymmetric monomers. Polymer-small molecule blends have previously been investigated[24, 25] in an attempt to produce ambipolar devices but rather than enhancing performance, the blending in these investigations appeared to diminish the peak electron and hole mobility of each component. Using a blend of small molecules and polymer to enhance the performance and improve deposition has been described in the patent literature.[26, 27] By blending a soluble, highly crystalline p-type small molecule organic semiconductor (OSC) with an inert or field-effect active polymer significant enhancement in performance is claimed. 2 Submitted to Here, two acene semiconductors first described by John Anthony, TIPS-pentacene[28] and diF-TESADT[18, 29] (Figure 1), are blended with both inert and field-effect active polymers with the expectation that peak device performance will be maintained while device uniformity is improved. OTFTs fabricated from soluble blends of polymer and small molecule are cast using spin-coating, which we will show causes preferential vertical phase separation of the two components. The small molecule is forced to the exposed interface, allowing large crystals to form within the channel region of the device. To evaluate the effect of the blend morphology devices were fabricated in a dual gate structure as well as a more conventional top gate design. The processing conditions are documented in the methods section, but Figure 1 (c) shows a schematic of the standard OTFT whilst Figure 2 (b) shows the dual gate device. Constructing transistors that have a bottom and top gate within the same device will elucidate differences in device performance between the bottom and top OSC interfaces, but will not differentiate between dielectric effects, channel injection and morphology changes. The leakage current between the two gates was always found to be less than the lowest measured off current thus allowing channels to be probed independently. Devices were operated in dual gate mode by biasing one gate to a constant voltage whilst sweeping the other to obtain transfer characteristics. This produced a shift in the threshold voltage dependent on the fixed gate voltage, which is consistent with dual gate operation. Figure 2 (a) shows the transfer characteristics for top and bottom channels within a single device, fabricated using a 1:1 by weight blend of TIPS-pentacene and the insulating polymer poly(α-methyl styrene) spin-coated onto the bottom gate dielectric. The choice of an inert polymer matrix for the dual gate device maximised any difference in mobility between top and bottom gate which might be due to vertical phase separation. Uniform semiconductor film formation was observed, whilst the saturation mobility of holes within the bottom 3 Submitted to channel was 0.10 ± 0.05 cm2V-1s-1 increasing to 0.5 ± 0.1 cm2V-1s-1 in the top channel. Moving from bottom to top gate also showed an improvement in on/off current ratios, reduced hysteresis and threshold voltage shifts from greater than +10 V to between -5 and -10 V. Processing issues, described in the methods section, forced the use of different dielectric materials for the bottom and top channel, which could account for the difference in performance seen. However, devices were analysed by a DSIMS technique (results below) which indicate a higher concentration of TIPS-pentacene in the top-channel. The maximum mobility achieved using TIPS-pentacene : poly(α-methyl styrene) in a top-gate-only device was found to be 0.69 cm2V-1s-1, which is only slightly higher than measured in the dual gate transistors showing that the altered structure does not adversely affect the top channel operation. In order to make an improvement in the mobility a change of polymer matrix is needed. It is suggested that phase separation (not necessarily vertical as described before) of TIPSpentacene and poly(α-methyl styrene) causes a reduction in the effective channel width and thus a lowering of the measured mobility for devices based on insulating polymers. Replacing poly(α-methyl styrene) with the amorphous p-type polymer poly(triarlyamine) (PTAA) (FlexInk) creates conduction pathways between separate crystalline pentacene-rich regions and improves the performance of the OTFT. Figure 3 shows typical transfer and output characteristics of top gate devices (channel length (L) of 60 μm and width (W) of 1000 μm) made from (a) TIPS-pentacene and (b) diFTESADT, both blended with PTAA. The highest mobility devices using TIPS-pentacene had a slight deviation from ideal square law behaviour at gate voltages greater than -50 V, due to the drain being biased to -40V. Charge injection appeared to be efficient, since there is a good linear output at low drain voltages and despite the higher currents within diF-TESADT based transistors no injection problems were observed. There is also a clear improvement in hole 4 Submitted to mobility over the devices made using TIPS-pentacene : poly(α-methyl styrene) blends. The highest mobility obtained was in a diF-TESADT : PTAA device which had a saturation mobility of 2.41 ± 0.05 cm2V-1s-1 and a linear mobility of 1.88 ± 0.04 cm2V-1s-1. In addition to high mobilities the important characterisation parameters for the devices remained constant and reproducible over the whole sample. A typical, non optimised sample (having lower quality evaporated source-drain electrodes but more transistors per sample) was tested and averages taken over 18 devices. The mean saturation mobility was found to be 0.66 ± 0.13 cm2V-1s-1 and the best device was 0.91 cm2V-1s-1. Similarly the mean threshold voltage was -7.2 ± 2.2 V and the on/off current ratio was 10(4.51 ± 0.32). Generally it was found that over 80% of the devices on a sample would show transistor behaviour. Table 1 clarifies the mobilities and on/off current ratios obtained for the various material and device designs employed. Devices fabricated in air using TIPS-pentacene blends had much lower mobilities (~0.1 cm2V-1s-1) compared to those made in nitrogen. These results are consistent with the degradation of pentacene OTFT performance due to H2O and O2 acting as a charge trapping dopants introduced during annealing of the semiconductor layer[30]. However, after fabrication in nitrogen, exposure to air resulted in only a slow reduction in device performance since the permeability of CYTOP to H2O and O2 is low. Figure 4 shows how the mobility as well as on and off currents varied over a period of four weeks for a diFTESADT based and a TIPS-pentacene based transistor. The TIPS-pentacene blend showed a slight drop in mobility after several hours while diF-TESADT blend transistors showed excellent stability and maintained a saturation mobility above 1.2 cm2V-1s-1 for the entire test. There was a gradual decrease in the on/off ratio due to increasing off current as bulk conduction in the channel became more significant. Within the dual gate OTFTs the lower performance of the bottom gate can be attributed to two effects. Firstly, there will be a larger number of charge trapping sites on the BCB5 Submitted to semiconductor interface due to the oxygen plasma treatment creating polar groups on the surface. Secondly, we believe that there is vertical separation of components within the semiconductor layer. During film formation phase separation of the polymer and the small molecular material occurs, however, due to the high surface energy of the substrate, and in particular the high polar component of this energy, there is preferential crystallisation of the TIPS-pentacene (or diF-TESADT) at the semiconductor-atmosphere interface. This therefore increases the fraction of molecular solid within the conducting channel of the transistor in the top gate configuration. Vertical profiling of the device structure by Dynamic Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (DSIMS) was used to confirm the distribution of the blend components. Cs ion bombardment was used to slowly sputter material from the film, and the resulting ejected ion species measured by mass spectrometer. Figure 5 shows the first signal to rise is the Si from the silyl group on the TIPS-pentacene molecule. The nitrogen signal (from the PTAA) can be seen to rise to a maximum approximately 20 - 30nm beneath the top surface. When scanned over the channel (a) the Si signal is seen to rise at a probed depth of ca. 50 nm, which could indicate an increase in concentration of TIPS at the glass substrate surface. This would explain why a field effect is still seen in bottom gate devices. When scanned over the electrodes, however, (b) the fluorine peak indicates the position of the self-assembled monolayer of pentafluorobenzene thiol (PFBT) and here TIPS seems to be excluded from the surface. The broadening in the F peak (which should in theory be a monomolecular layer <1nm thick) is due to a combination of a variable rate of etch for different materials in the layer and a slight spread in the energy density of the Cs ion beam. The gold signal rises immediately afterwards as the profiling reached the source and drain electrodes, and finally the Si signal rises once more indicating profiling into the glass substrate. A depth profile of an area between the source and drain electrodes showed the same distribution of the TIPS and PTAA, indicating that the phase separation occurs over the entire area of the spin coated sample. 6 Submitted to The TIPS-pentacene : PTAA system was chosen to illustrate the suspected vertical phase separation, as each component contains an element that identifies it as being located at a certain depth. Using this analysis, it is apparent why a top-gate device may perform better than a bottom-gate. Although there is sufficient TIPS-pentacene in the bottom channel to allow a reasonable field-effect mobility, the higher concentration in the top channel provides an explanation of the better performance. The vertical phase separation in this system is assumed to apply to all small molecule polymer blends in this study. The films were also studied using polarised light microscopy to observe the morphology of the crystallites and atomic force microscopy (AFM) to map the surface of the semiconductor which forms the conducting channel within the OTFT. Figure 6 shows both diF-TESADT and TIPS-pentacene based blend films. It is clear that some crystallisation of the molecular material into spherulitic-type structures has occurred. Crystallisation occurs over the whole sample when annealed for longer than 2 min at 100 °C, less than this quenches the sample leaving some amorphous regions which are not suitable for high performance devices. The AFM shows a clear difference between the amorphous part of the film, with a r.m.s. surface roughness of 6.4 nm, and the crystallites, with a surface roughness of 18 nm. This increase in surface roughness and the change in appearance of the film suggest that some of the TIPSpentacene is forming on the top surface during crystallisation – the situation that we require for good top gate OTFT performance. The optical micrographs also show the effect of contact induced crystallisation on PFBT coated gold contacts[11]. Much larger and more spherulitic crystals are produced on the gold surfaces in the case of diF-TESADT blends where it is suggested that fluorine interactions promote the crystallisation. In the case of TIPS-pentacene blends the effect is less pronounced as the same F-F interactions do not exist, which also agrees with the better charge injection observed in the diF-TESADT devices. Further annealing of the diF-TESADT based transistors at 100 °C after fabrication resulted in a lowering of the off current, for example after 1 hour the on/off current ratio typically 7 Submitted to increased from approximately 103.5 to 104.2. This is also consistent with an improvement in vertical phase separation on heating which would reduce bulk conduction through the semiconductor film and thus lower the current in the off state of the device. Simple unipolar inverter circuits were constructed using TIPS-pentacene and diFTESADT blend transistors showing their possibility for use in real devices. We have demonstrated that an inverter gain of greater than 10 and good noise margins can be achieved. Again with a view to commercial viability we have shown that devices can be fabricated on poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) films with very little loss of performance. Using a TIPSpentacene : PTAA blend for the semiconductor, saturation mobilities of up to 1.13 ± 0.05 cm2V-1s-1 were measured and threshold voltages and on/off current ratios remained the same as for the devices made on glass. The key feature here was the maximisation of the substrate surface energy by oxygen plasma in order to enhance uniform film formation and vertical phase separation of the blend components. In conclusion, we have shown a significant improvement in peak device performance and reduced device variability by combining the film-forming properties of polymers and high mobility due to high degree of crystallinity of small molecules in a blend device as compared with other small molecule devices.[11] The use of an insulating polymer matrix demonstrated the improved film forming properties of the blend system, while use of the field-effect active polymer matrix maintained this and increased the mobility. The dual gate device structure suggested that vertical phase separation of the small molecule and the polymer occurs, indicated by improved top channel performance over bottom channel within the same device. Although this could be explained by the different dielectrics and their respective interface properties, DSIMS measurements confirmed that there was a higher fraction of small molecule at the top surface. 8 Submitted to The comparison of diF-TESADT and TIPS-pentacene in identical blend systems show that diF-TESADT is more crystalline, air-stable and higher performing. Optical micrographs show larger crystallite formation on the electrodes which extend further into the channel, appearing to correlate with the higher performance seen, reaching a mobility of 2.4 cm2V-1s-1. Experimental: The standard top gate transistors were fabricated on glass substrates (EAGLE 2000 from Corning) with evaporated gold (Au) source and drain electrodes. A 900 nm layer of the fluorocarbon polymer CYTOP (Asahi Glass) was used as the dielectric and gate electrodes were evaporated aluminium (Al). The substrates were cleaned by sonication in detergent solution (DECON 90) and rinsed with deionised water. Source and drain electrodes were approximately 40 nm thick with a 60 μm channel length. Their surface was modified by immersion in a 5x10-3 mol l-1 solution of pentafluorobenzene thiol (PFBT) in isopropanol for 5 min and then rinsed with pure isopropanol. The semiconducting layer was spin coated from a solution of either TIPS-pentacene or diF-TESADT plus the polymer matrix (poly-a-methylstyrene and polytriaryl-amine) 1:1 by weight at 4 wt% concentration of solids in tetralin. Spin coating was carried out at 500 rpm for 10 sec then 2000 rpm for 20 sec and was followed by drying at 100 °C for 15 min in nitrogen to obtain layers with a thickness of ~70 nm. CYTOP was then spin coated at 2000 rpm for 60 sec and dried at 100 °C for 20 min before the gate electrode was evaporated. Double gate devices were fabricated using ITO coated glass substrates. Divinyltetramethyldisiloxane bis-benzocyclobutane (BCB) solution was spin coated at 1500 rpm for 60 sec before being UV cured and then heat cured at 300 °C to form the bottom gate dielectric. The devices were then completed as for the standard structure with Au source and drain, CYTOP top gate dielectric and Al top gate contact. It was not possible to use identical 9 Submitted to layers for both top and bottom gate dielectrics in the double gate device, due to processing issues. Although CYTOP uses a fluorinated solvent and will not dissolve the small molecule when spun on top of the OFET blend layer, it also has a very low surface energy and, when using it as a bottom gate dielectric, coating layers on top of CYTOP is very difficult. Conversely, the solvent used with BCB will also dissolve the active layer, thus destroying the device. Before PFBT treatment the samples were oxygen plasma treated for 2 min at 80W R.F. power in order to increase the surface energy of the BCB layer from around 35 mJm -2 to 73 mJm-2. This increase is primarily due to the introduction of a polar component to the surface energy not present on pristine BCB. The devices using PET films as the substrate were produced in a similar fashion to the standard devices. Plastic films were cleaned by sonication in acetone and isopropanol, and oxygen plasma treatment was used to increase the substrate surface energy before PFBT treatment. Atomic force microscopy was carried out in close contact mode using a Pacific Nanotechnology Nano-R2 machine and a Nikon Eclipse E600 POL was used to image the films between crossed polarisers. In order to examine the phase separation of the TIPS-pentacene and polymer matrix, DSIMS (Dynamic Secondary Ion Mass Spectroscopy) was performed on the spin-coated TIPS-pentacene : PTAA blend film using an Ion-Tof 'ToFSIMS IV' instrument (analysis performed by Intertek MSG, Wilton, UK). During DSIMS, ion bombardment is used to slowly sputter material from the film, and the ejected ion species measured by a mass spectrometer. The primary ion species used were Cs ions and elements were selected so as to uniquely identify each component: Si in TIPS-pentacene; N in PTAA; F in the PFBT monolayer; Au in the source-drain electrodes and Si in the bottom layer was assumed to be from the glass substrate. The results were normalised to their respective maxima, as there is a large variation 10 Submitted to in sensitivity for different elements using this technique. Therefore DSIMS cannot be used to indicate relative concentrations between elements, but it can show the concentration variation for a particular element throughout the depth of a film. A thin layer of gold was sputtered onto the surface of the semiconductor film to prevent charging of the sample. The depth of the trench made by the ion beam was measured by profilometer (Dektak 8) and used to convert the time signal from the DSIMS into a measure of depth. Electrical characterisation of the OTFTs was carried out in either a nitrogen atmosphere (< 0.1 ppm oxygen) or in air using a semiconductor parameter analyser. Mobilities were calculated in both the linear, μlin, and saturation, μsat, regimes from the transfer characteristics, using a standard thin film field-effect transistor model: sat L 1 2ID W Ci VG2 (1) lin L 1 I D W CiVD VG (2) In these expressions, Ci is the geometric capacitance of the dielectric layer which for the case of CYTOP was measured to be 2.10 ± 0.09 nFcm-2 and for BCB was 1.12 nFcm-2. This measurement was carried out using a parallel plate capacitor on a Solartron 1260 impedance analyzer. From Ci a value of 2.14 was estimated for the dielectric constant of CYTOP which is only slightly higher than the value of 2.1 quoted by Asahi Glass Co. [1] H. Sirringhaus, T. Kawase, R. H. Friend, T. Shimoda, M. Inbasekaran, W. Wu, E. P. Woo, Science 2000, 290, 2123. [2] G. H. Gelinck, H. E. A. Huitema, E. Van Veenendaal, E. Cantatore, L. Schrijnemakers, J. Van der Putten, T. C. T. Geuns, M. Beenhakkers, J. B. Giesbers, B. H. Huisman, E. J. 11 Submitted to Meijer, E. M. Benito, F. J. Touwslager, A. W. Marsman, B. J. E. Van Rens, D. M. De Leeuw, Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 106. [3] Y. Noguchi, T. Sekitani, T. Someya, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89. [4] R. H. Reuss, B. R. Chalamala, A. Moussessian, M. G. Kane, A. Kumar, D. C. Zhang, J. A. Rogers, M. Hatalis, D. Temple, G. Moddel, B. J. Eliasson, M. J. Estes, J. Kunze, E. S. Handy, E. S. Harmon, D. B. Salzman, J. M. Woodall, M. A. Alam, J. Y. Murthy, S. C. Jacobsen, M. Olivier, D. Markus, P. M. Campbell, E. Snow, Proc. IEEE 2005, 93, 1239. [5] C. D. Dimitrakopoulos, P. R. L. Malenfant, Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 99. [6] S. Steudel, K. Myny, V. Arkhipov, C. Deibel, S. De Vusser, J. Genoe, P. Heremans, Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 597. [7] S. Steudel, S. De Vusser, K. Myny, M. Lenes, J. Genoe, P. Heremans, J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 99, 114519. [8] J. R. Sheats, J. Mater. Res. 2004, 19, 1974. [9] H. Hofstraat, Polytronic 2001, Proceedings 2001, 1. [10] K. P. Weidkamp, A. Afzali, R. M. Tromp, R. J. Hamers, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 12740. [11] D. J. Gundlach, J. E. Royer, S. K. Park, S. Subramanian, O. D. Jurchescu, B. H. Hamadani, A. J. Moad, R. J. Kline, L. C. Teague, O. Kirillov, C. A. Richter, J. G. Kushmerick, L. J. Richter, S. R. Parkin, T. N. Jackson, J. E. Anthony, Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 216. [12] S. K. Park, J. E. Anthony, T. N. Jackson, Ieee Electron Device Letters 2007, 28, 877. [13] K. C. Dickey, T. J. Smith, K. J. Stevenson, S. Subramanian, J. E. Anthony, Y. L. Loo, Chemistry of Materials 2007, 19, 5210. [14] J. E. Anthony, J. S. Brooks, D. L. Eaton, S. R. Parkin, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 9482. [15] D. J. Crouch, P. J. Skabara, J. E. Lohr, J. J. W. McDouall, M. Heeney, I. McCulloch, D. Sparrowe, M. Shkunov, S. J. Coles, P. N. Horton, M. B. Hursthouse, Chemistry of Materials 2005, 17, 6567. [16] I. McCulloch, M. Heeney, C. Bailey, K. Genevicius, I. Macdonald, M. Shkunov, D. Sparrowe, S. Tierney, R. Wagner, W. M. Zhang, M. L. Chabinyc, R. J. Kline, M. D. McGehee, M. F. Toney, Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 328. [17] H. Sirringhaus, P. J. Brown, R. H. Friend, M. M. Nielsen, K. Bechgaard, B. M. W. Langeveld-Voss, A. J. H. Spiering, R. A. J. Janssen, E. W. Meijer, P. Herwig, D. M. de Leeuw, Nature 1999, 401, 685. [18] S. Subramanian, S. K. Park, S. R. Parkin, V. Podzorov, T. N. Jackson, J. E. Anthony, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2706. [19] S. K. Park, T. N. Jackson, J. E. Anthony, D. A. Mourey, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 063514. [20] D. Guo, T. Miyadera, S. Ikeda, T. Shimada, K. Saiki, J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 102, 023706. [21] R. L. Headrick, S. Wo, F. Sansoz, J. E. Anthony, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92. [22] B. H. Hamadani, D. J. Gundlach, I. McCulloch, M. Heeney, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 243512. [23] M. Berggren, D. Nilsson, N. D. Robinson, Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 3. [24] Y. Hayashi, H. Kanamori, I. Yamada, A. Takasu, S. Takagi, K. Kaneko, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 052104. [25] A. Babel, J. D. Wind, S. A. Jenekhe, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2004, 14, 891. [26] B. A. Brown, J. Veres, R. M. Anemian, R. T. Williams, S. D. Ogier, S. W. Leeming, Wo Patent 2005055248, 2005. [27] S. D. Ogier, J. Veres, M. Zeidan, Wo Patent 2007082584, 2007. [28] J. E. Anthony, D. L. Eaton, S. R. Parkin, Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 15. [29] S. K. Park, C. C. Kuo, J. E. Anthony, T. N. Jackson, in Ieee International Electron Devices Meeting 2005, Technical Digest, IEEE, New York 2005, 113. 12 Submitted to [30] T. D. Anthopoulos, G. C. Anyfantis, G. C. Papavassiliou, D. M. de Leeuw, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 122105. Received: ((will be filled in by the editorial staff)) Revised: ((will be filled in by the editorial staff)) Published online on ((will be filled in by the editorial staff)) Architecture Channel μsat μlin ION / IOFF TIPS-pentacene : poly(α-methyl styrene) DUAL GATE Bottom Top 0.10 ± 0.05 0.5 ± 0.1 – – 104.1 104.8 TIPS-pentacene : poly(α-methyl styrene) TOP GATE Top 0.7 0.6 105.3 TIPS-pentacene : PTAA TOP GATE Top 1.1 0.7 105.2 diF-TESADT : PTAA TOP GATE Top 2.41 1.88 104.2 Table 1: Summary of the mobilities and on/off current ratios obtained for the various material and device designs employed. (a) (b) Si Si S F F S Si Si (c) Figure 1: Chemical structures of (a) diF-TESADT and (b) TIPS-pentacene and (c) a schematic diagram of the standard device structure (PFBT = pentafluorobenzene thiol). 13 Submitted to (a) -4 10 5 Bottom channel = 0.06 cm /Vs 2 Top channel = 0.44 cm /Vs 2 -5 10 4 -6 3 -3 2 -9 10 1/2 -8 10 ID(sat) ID / A / 10 A VD = -60 V -7 10 1/2 10 1 -10 10 VT(bottom) = +12.6 V VT(top) -11 10 40 20 0 -20 = -9.0 V -40 0 -60 VG / V (b) Figure 2: Dual gate device using a TIPS-pentacene : poly(α-methyl styrene) blend, (a) transfer curves for the separate channels and (b) a schematic of the device structure (PFBT = pentafluorobenzene thiol). 14 Submitted to -4 VD = -4 V VG = 0 to -60 V VD = -40 V -5 10 (VG= -10 V) -30 6 -6 -8 ID 1/2 10 -20 ID / A 4 -3 -7 10 / 10 A 1/2 10 ID / A -40 8 10 (a) -10 -9 10 VT = -8.9 V 2 -10 10 0 -11 10 10 0 0 -10 -20 -30 -40 -50 -60 0 -10 -20 -30 -40 -50 -60 VD / V VG / V (b) -140 VD = -2 V -4 10 14 VD = -40 V VG = 0 to -60V -120 -5 12 10 6 -8 10 4 VT = -5.0 V -10 10 -60 -40 -20 -9 10 10 ID / A -3 / 10 A -7 10 -80 1/2 8 ID(sat) ID / A 10 1/2 -100 10 -6 0 2 0 0 -10 -20 -30 -40 -50 -60 0 -10 -20 -30 -40 -50 -60 VD / V VG / V Figure 3: Transfer and output curves of typical top-gate (a) TIPS-pentacene and (b) diFTESADT blend transistors with saturation mobilities of ~1 cm2V-1s-1 and >2 cm2V-1s-1 respectively. 15 Submitted to -1 1.2 2 (sat) / cm V s -1 1.4 1.0 0.8 0.6 -5 I/A 10 ON current -7 10 -9 10 OFF current 0 2 4 10 100 1k 10k 100k Exposure time in air / min Figure 4: Air stability of TIPS-pentacene and diF-TESADT (Open and Filled symbols respectively) measured over a period of four weeks. 16 Submitted to (a) Silicon (TIPS) 1.0 Nitrogen (PTAA) (b) Silicon (TIPS + Substrate) Silicon (TIPS) 1.0 Nitrogen (PTAA) Gold Fluorine (PFBT) (Electrodes) Silicon (Substrate) Normalised Count 0.8 Normalised Count 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.2 Gold 0.0 0.0 0 20 40 60 0 Depth probed into film / nm 20 40 60 80 Depth probed into film / nm Figure 5: DSIMS depth profile of TIPS-pentacene: PTAA film on silicon substrate with PFBT treated gold source and drain electrodes. The graphs show the phase separation, (a) in the channel and (b) over the electrodes of the TIPS-pentacene material (as indicated by the Si signal) closer to the air interface when compared with the PTAA (seen in the N signal). 17 Submitted to (a) (b) Figure 6: Polarised microscopy and AFM images of (a) TIPS-pentacene : PTAA, (b) diFTESADT : PTAA and (c) partially crystallised films with A being the amorphous and B being the crystalline region. 18 Submitted to The table of contents entry Here we show a double gate device used to demonstrate that a blended formulation of semiconducting small molecule and a polymer matrix can provide high electrical performance within thin film field effect transistors (OTFTs) with charge carrier mobilities of greater than 2 cm2V-1s-1, good device to device uniformity and the potential to fabricate devices from routine printing techniques. TOC Keyword: Organic Transistor J. Smith, S. Ogier, M. Heeney, J. E. Anthony, I. McCulloch, J. Veres, D. D. C. Bradley, T. D. Anthopoulos, R. Hamilton* Title: High Performance Polymer-Small Molecule Blend Organic Transistors ToC figure ((55 mm broad, 40 mm high)) 19 Submitted to Supporting Information should be included here (for submission only; for publication, please provide Supporting Information as a separate PDF file). 20