A Process approach to syllabus design takes into account task

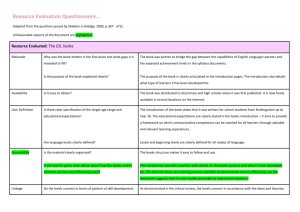

advertisement

A Process approach to syllabus design takes into account task demands and the way language is processed by the leaner. a) Discussion of the theoretical basis for this approach. b) Evaluation of the implications for such a syllabus design in a professional context with which I am familiar. 英文科 陳惠珍 1. Introduction A syllabus can facilitate the teaching and learning of language and contribute to the learners’ achievement of communicative competence because it provides a blueprint for teachers and examiners to follow. Some syllabuses focus on specifications of content (product syllabuses); others include guidance on teaching and learning as well as content (process syllabuses). This essay begins by describing different views of syllabus design, discussing both product and process approaches. Some examples of each will be included. Following this, a rationale for the process approach will be discussed in which the theoretical bases in language description and language teaching and learning are focused on. The implications and limitations of the process approach will be considered with specific reference to my own teaching context. 2. A brief literature review 2.1. Syllabus design Stern (1984:5) adopts a traditional view when he indicates that syllabus design is ‘more or less’ accepted as ‘ the specification of the what of instruction or its content, the definition of a subject, the ends of instruction, what is to be achieved, and what will be taught.’ Over the years this traditional focus on content has been modified as successive educationists have introduced elements to do with the “how” of the curriculum, including teaching and learning methods. For example, Candlin (1984:3) proposes that ‘an interactive syllabus suggests a model which is social and problem-solving.’ Breen (1987:82) goes further when he claims that syllabus design is ‘a decision-making process’ related to ‘a plan of what is to be achieved through teaching and learning.’ He (1987:83) concludes that ‘any syllabus is therefore the meeting point of a perspective upon language itself, upon using language, and upon teaching and learning’ in a commonly and harmoniously accepted interpretation. Nunan (1988) in his definition of syllabus attempts to bring together both content and the interactive elements highlighted by Breen and Candlin. He sees it as ‘a statement of content which is used as the basis for planning courses of various kinds.’ (op cit:6) He goes (op cit:12) on to specify the elements of the content as ‘grammatical structures, functions, notions, topics, themes, situations, activities, and tasks,’ indicating that both ‘the learners’ purpose’ and ‘the syllabus designer’s beliefs about the nature of language and learning can have a marked influence on the shape of the syllabus,’ which may be product-oriented or process-oriented. The key issue that has emerged in the development of theory in ELT syllabus design appears to be managing the tensions between content (product) and process (methods of teaching and learning). Nunan (1988) points out that this dichotomy can be viewed either narrowly or broadly. The narrow view sees the syllabus design as focusing on the ordering of content. The broad view, however, sees syllabus design as including teaching and learning. 2.2. What value systems have an influence on syllabus design in the wider educational context? Decisions influencing whether a narrow or broad view of syllabus is taken may be orientated by three ideologies: classical humanism, reconstructionism, and progressivism. White (1988:24) points out that these different values on the nature and purposes of education have given rise to diverse realizations of syllabus design, more or less narrow or broad in focus. 2.2.1. Classical humanism Skilbeck (1982:17) indicates that the orientation of classical humanism ‘is always towards achieving or recapturing a standard.’ It is the standard that ‘constitutes both an ideal to be striven for and a heritage to be transmitted.’ Such a value aims to promote broad intellectual capacities and mastery of controlled knowledge through conscious understanding, unit-by-unit learning and deliberate practice. In language learning and teaching this type of syllabus focuses on mastery of the language, often with the intention of eventually using the language to read the literary canon. The syllabus would be language focused, accuracy focused, and most probably grammatically structured. The methodology associated with this might be grammar translation. This is supported by Clark’s statement (1987:7) that classical humanism favours a methodology which emphasizes ‘ conscious study and deliberate learning’ under the teacher’s presentation of knowledge elements (i.e. language) and rules, which are divided and sequenced from the simple to the more complex. Learners are expected to produce the ends of the instruction in new contexts, for example, create new sentences using grammatical items and vocabulary learnt in class. Classical humanism has some points of similarity with Confucian traditions of learning where a student must formally acquire a body of knowledge for future use. The traditional processes of learning are similar too - learning the rules, memorizing, recombining what has been learnt in new contexts and so on. It may be for this reason that in oriental societies the grammar translation approach is still part of current practices. 2.2.2. Reconstructionism Clark (1987:15) states that reconstructionists express a special concern with ‘the practical aspect of education’ and he emphasizes ‘the promotion of an ability to communicate,’ indicating that reconstructionism gives rise to a ‘objective-driven’ curriculum, in which predetermined objectives in terms of learners’ needs are achieved by learners through activities. He (1987:18) further implies that the methodology related to reconstructionism lays stress on ‘ rehearsal of eventual global end-objectives’ based on the performance of ‘various part-skills of a particular behaviour.’ The development of notional-functional syllabuses is an example of such a value. White (1988:75) notes that a notional-functional syllabus sets objectives according to two elements, notions or concepts (e.g. time or space) and functions, with which the use of language is classified. Thus the syllabus is no longer determined solely by grammatical content, but also takes into account the communicative functions and notions that learners may wish to learn. The methodology associated with such syllabuses encourages activities to rehearse end-objectives so that learners could eventually achieve objectives. Learners practice notions and functions in realistic activities, like practicing saying greetings. Widdowson (1990:132) states that the subject language of notional-functional syllabuses is taught as ‘units of communicative performance for accumulation.’ Such a syllabus is often cyclical. In my own teaching context, notions and functions figure in the syllabuses and are dealt with in progressively detailed ways in successive years. So, for example, pupils in the first year might practice friendly greetings and interactions in the context of their classmates, while in year five they might be participating similar functions in the context of a formal job interview. The teaching method can be set to focus on rehearsal in class for possible future use. 2.2.3. Progressivism In Clark’s (1987:49) view, Progressivism offers a ‘learner-centered approach to education, which attempts to promote the pupil’s development.’ The central idea of it is ‘growth through experience,’ which learners acquire with their creative problem-solving capacities. Education is viewed ‘as a means of providing learners with experience’ which ‘enable them to learn how to learn by their own efforts.’ He goes further to indicate that progressivism allow the teacher and learners to decide what to learn and how to learn it. The methodology under such a value focuses on providing opportunities for learners’ spontaneous learning through engaging in communicative activities. It is clear that learners’ experience and creativity are valued. The teacher and learners can participate together the common teaching and learning activity. In language learning this value appears to be very close to Breen’s 1987 view of process syllabus where learners’ learning process should be valued. 2.3. Definition of the process approach Breen (1984: 52) notes that process approach is an alternative, which ‘provides a change of focus from content toward the process of learning in the classroom.’ In other words, the focus is on the means as well as the ends. For Nunan (1988:40), the process approach means the activities ‘through which knowledge and skills might be gained.’ White (1988:46) takes a rather more extreme view when he says that ‘content is subordinate to the learning process and pedagogical procedures.’ This is an overstatement of the balance in my view. Breen was making the point that the method through which objectives were achieved was as important as the objectives, not necessarily more important. Learners need to learn something – words, structures, patterns – as well as learning effectively. The change in focus from wholly product-oriented syllabuses design to an approach which acknowledged the importance of learners, teaching and learning, was an important landmark in education generally. Breen (1987:168) summarizes the process syllabus as not only offering ‘a means whereby the selection and organization of subject-matter become part of the decision-making process’ but also presenting ‘a framework within which teacher and learners decide how they should best work upon subject-matter.’ This is a learner and learning centered approach to teaching and learning where content and method are closely harmonized. 2.3.1. A Task-based syllabus One particular type of process syllabus is a task-based syllabus, where the emphasis is as much on what learners do in order to learn as the eventual objectives. Breen (1987:161) states that a Task-based syllabus is achieved in two types of tasks: ‘communication tasks’ and ‘learning tasks.’ Communication tasks prioritize ‘the purposeful use of the target language’ in the real sharing of meaning. Learning tasks aim to explore ‘the workings of knowledge systems themselves’ especially ‘how these may be worked and learned.’ That is, a learning task serves to ‘facilitate a learner’s participation’ in communication tasks while a communication task ‘facilitates the learning of something new’ and solves a problem. A learning task aiming to prepare for a communication task or solve an earlier problem can generate real communication among participants. They both require participants to engage the underlying competence in undertaking interpretation, expression, and negotiation in actual communicative events. Breen (1987:162) indicates that ‘learners can cope with the unpredictable, be creative and adaptable, and often transfer knowledge and capability across tasks.’ In a Task-based syllabus, communicative abilities and learning capability are achieved simultaneously through the new language. 2.3.2. A Procedural syllabus An early example of a task-based syllabus was the Procedural syllabus developed in the Bangalore Project by Prabhu and his colleagues. They were dissatisfied with the Structural-Oral-Situational method and developed a task-based syllabus. Basically, the aim of the procedural syllabus, as Prabhu (1988: 52) indicates, was the development of ‘grammatical competence,’ which was achieved through a syllabus as comprising a series of graded meaning-focused activities, where each activity was divided into a pre-task and a task phase. In Prabhu’s (1987: 53 & 68) statement, the former is ‘teacher-guided whole –class’ demonstration; the latter is attempted by learners independently. Learners undergo ‘the process of understanding, thinking and stating outcomes’ and thus achieve linguistic competence by accomplishing tasks, which enable them to abstract rules or principles from conveying meaning by trial and error. In this early task-based approach we find a syllabus which consists of a list of graded tasks and a classroom methodology which was teacher fronted ( in that the teacher rehearsed the task for the pupils ), and learner centered ( because the real task was a challenge for individuals ). The close teacher guidance was appropriate for the educational context in which the project was located. 2.4. Rationale for the process approach 2.4.1. Changing views of language We have seen above that classical humanism saw language as a kind of “gold standard”- a body of knowledge to be learnt. In the 20th century, research into language use, much of it driven by social economic changes (immigration, mass production and Americanization of commerce) led to a re-appraisal of language learning, with a focus on communicative objectives rather than mastery. This was reflected in syllabus design. For example, as noted above, notional-functional syllabuses reflected a new awareness of how people use language in communicating. People also had changing views of language since many of them wanted to learn languages for work purposes, not to read literature, for example. Unfortunately, the methodology associated with notional-functional syllabuses was product orientated – as noted above it was rehearsal for future performance. However, this focus on learners’ needs and targeted objectives for learning paved the way for later developments in communicative teaching. 2.4.2. Emergence of communicative methodology Thus communicative language teaching (CLT) emerged from criticism of notionalfunctional syllabuses, and the product orientated methods used (typically presentation, practice & production ). Communicative language teaching seeks to explore a practical, diverse and wide-ranging approach to language teaching, in which the language is used for real communication during the processes of learning. Teaching serves to facilitate these learning processes, rather than only being a presentation or rehearsal of knowledge. Its purpose is to develop learners’ communicative competence through their engagement with tasks and meaning-focused activities. CLT is learning language through communication not for communication. 2.4.3. Contributions of learners The process approach emphasizes learners and their contributions to the learning and teaching process. Breen (1987: 158) views learners’ underlying abilities of interpretation, expression, and negotiation as ‘the catalyst for the learning and refinement of knowledge itself.’ Learners’ communicative abilities and knowledge and their expectations of language learning contribute to language learning and teaching processes. Different learners with various expectations, needs, interests, and motivations adopt different means of interaction in achieving communication. 3. Evaluation 3.1. The profile of my teaching context The students whom I am teaching major in vocational subjects (e.g. business management or advertisement design and layout), and are aged from 15 to18. They grew up in the environment of their first language of Taiwanese or Mandarin. Most began to learn English at the age of 12 or 13 but some of them started earlier. Most of them will have received product-orientated instruction. Generally, their proficiency falls rather below intermediate level. When I have tried to investigate my learners’ perceived needs, most of them are not interested in learning English, partly because they rarely have successful experience. They are short of confidence and unused to taking responsibility for their own learning. The reasons they learn English are that English is a compulsory subject and good English grades can give them a better chance to enter vocational college of their choice. At present, they receive two 50-minute periods of English class per week, in classes of about 40-45 students. This gives teachers limited time to do the work required for the year. The coursebooks and syllabuses are product orientated in that they mostly offer lists of vocabulary, grammar, sentence structures, or samples of conversation demonstrating different functions. Such syllabuses and materials have a strong influence on options for teaching method, since the focus on learning language content not learning to use language. In any case, most of the educational administrators would be unlikely to accept task-based teaching and learning classrooms, which are different from the traditional ones. There seems to be a conflict in my teaching context. Although there is an expressed aim for young Taiwanese to become efficient users of English, the resources and time constraints mitigate against this. 3.2. Implications of the process approach for my teaching and my students learning 3.2.1. Decisions made by the teacher and learners In order to create effective learning and appropriate teaching, the teacher, considers the learners’ characteristics, such as their abilities, needs and interests, and guides them to make decisions about what they are going to learn, what tasks they are going to undertake, and especially how they are going to learn it. For the type of students I teach such involvement in decision-making might be quite intimidating. They would probably feel that learning is easier if learners know what is taught and how it is taught, and how they are expected to learn. There is very little scope for students to participate the choice of teaching materials. However, I can guide them to decide their own extensive reading, like short stories or magazines. And I could also provide limited choice of activities at infrequent intervals, e.g. once or twice a year. 3.2.2. Exposure to authentic resources A variety of authentic materials, related to tasks, activities and real language use, is adopted to expose learners to English. This involves learners not only acquiring real language but also accommodating themselves to real communication out of the classroom. However, most of my students are really false beginners, or at best very low intermediate, and English is a foreign language to them. In this way, authentic resources may make them bewildered and demotivated. Nevertheless, authentic materials can be very motivating to students if they can successfully achieve a task goal using them. The skill I need to learn is to develop simple tasks using authentic materials e.g. as one can see in the Cobuild series. 3.2.3. Tasks within meaningful activities elicit learning. Language teaching can encourage learners to find out means of learning by offering them abundant opportunities for using the target language to develop their communicative competence. Learners’ initial capabilities are recognized and exploited in undertaking tasks. They discover their own routes to learning independently or cooperatively. In undertaking tasks of problem-solving activities, learners acquire communicative competence through negotiation of meaning whereas the target language and unpredicted language occur simultaneously and lead to acquisition of real language use. When giving tasks, the teacher has to consider individual learning abilities, for example, that some students may not be able to find ways to carry out the tasks and fail to learn. They may use Taiwanese or Mandarin. Nevertheless, task design should direct the students to focus on English; the teacher has to offer sufficient assistance to them and also to arrange capable students in the same pair or group. 3.2.4. Teaching is to facilitate learning. As I noted above, in Taiwan the circumstances of lack of a teaching time, large classes and an examination culture tend towards a product approach in which teachers present for learners to learn. This leads to frustration for both teachers and learners since the learners do not learn to use the language. The introduction of some communication tasks might enable some real learning to take place. However, this really needs some impetus from the education ministry e.g. in offering a little more time. Even out of school English clubs which work well in some countries (e.g. Malaysia ) are difficult to organize in teaching because pupils have a great deal of homework. 3.2.5. Learners’ contributions From the view of the process approach, both learners’ initial capabilities and involvement in tasks contribute to their own learning. The goal of language learning is to develop communicative competence, not solely to accumulate language knowledge for the purpose of passing an exam. In my teaching I may spoon feed my students too much instead of making them find answers for themselves. I should encourage the students to value their own abilities and suggest they share the responsibility for the successful language learning by selecting challenging tasks and giving them time to work out the answers for themselves. 3.3. Limitation of the process approach for my teaching context 3.3.1. Are learners’ decisions made appropriately? A central value in the process approach is that learners have rights to help to decide the content of learning. However, the maturity of my learners’ decisions and their awareness of language are in question. Most of them are not proficient language learners and do not know what language is about. It may lead to aimless learning if the content is decided according to my students’ interests, imagination, or creativity. This is the reason why the administration cannot allow students full participation in the choice of the content. As discussed in 3.2.1., however, I can offer them some opportunities where they can make choices. Teachers can also act as proxy and make sure that the content of lessons is appropriate to learners needs. As I noted above, I regularly try out to find out more about my students needs and interests. 3.3.2. In a mixed-ability class are all the learners capable of finding their own ways of learning? From the process approach, teaching can activate the learners’ autonomy of learning without the teacher’s intervention. However, it may fail to facilitate learning of the false beginners or weak learners who lack confidence and self-esteem. For example, they may feel insecure and bewildered in carrying out tasks. Unfamiliarity may cause them unable to discover paths to their own learning without my instruction. Tasks can be designed in pair work or group work of mixed-level learners, and the weak learners may feel more confident from collaborative learning and learn. My classes are mix ability and I try to use a wide range of different tasks so that my learners can experience different ways of learning. Only in this way will they be able to find their preferred ways. 3.3.3. Is time sufficient for genuine communication? Learners are provided with a variety of chances to acquire the target language and achieve communicative competence through carrying out tasks. Frankly speaking, the learners may require much more time to practice genuine communication than lessons allow. Thus I may offer my pupils some clues or support for their communication. Again the most feasible approach is probably to introduce simple communication tasks and allow the students to become familiar with each task type before going on to the next type. This will reduce time wasted. Another technique is for teachers to use English as the instructional and social language in the classroom. Again, this can be fairly artificial and graded to begin with (e.g. simple greetings and instructions, use of mime), and gradually become more natural as students learn to understand. 4. Conclusion My students are studying in a vocational senior high school. Their course of study is job-oriented. Work in Taiwan frequently involves the use of English, and successful people in business will almost certainly be reasonably proficient. The process approach, therefore, has much to offer in my teaching context because it aims towards meaningful language learning and it focuses on the development of learners’ communicative competence. Within the process approach, the learners’ contribution is valued to maintain their efforts for English learning, which can be developed through completing tasks within meaningful activities. However, the traditional product approach is still very widely adopted even though it has received a lot of criticism. It cannot be denied that the product approach offers pedagogic convenience for the teachers in Taiwan, where English is taught in a large mixed-ability class, where learners regard English learning as a subject for entering a higher better school. I have argued that the ordinary teacher has to adapt the constraints in which she or he works. This probably means following the product-oriented approach for much of the time at present. I have shown that in small increments learning and learner centered tasks and activities can be introduced. The teachers can combine these two approaches to language teaching and learning. The adoption of these plural syllabuses in my teaching context can best suit for learners to learn to use the language, and to prepare them for the national entrance examination. References: Breen, M.P.1987. ‘Contemporary paradigms in Syllabus Design, Part 1.’ Language Teaching Vol.20, No.2 pp 81 – 92. Breen, M.P.1987. ‘Contemporary paradigms in Syllabus Design, Part 2.’ Language Teaching Vol.20, No.3 pp 157 – 174. Brumfit, C.J. (Ed.) 1984. Oxford: Pergamon. Clark, J.L.1987. General English Syllabus Design. (ELT Documents 118) Curriculum Renewal in School Foreign Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. H. G. Widdowson, 1990. Aspects of Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press Nunan, D.1988. Syllabus Design. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Prabhu, N.S.1987. Second Language Pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Skilbeck, M.1982. ‘Three Educational Ideologies’ in T. Horton and P. Raggat (Eds.) Challenge and Change in the curriculum. Sevenoaks: Hodder and Stoughton. White, R.V. 1988. The ELT Curriculum: Design, Innovation, and Management. Oxford: Blackwell.