Labor Law - UB Law Journal

advertisement

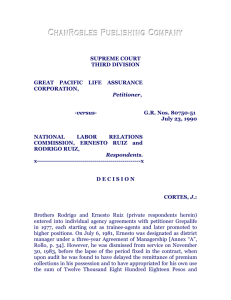

SUPREME COURT DECISIONS LABOR LAW JUST CAUSE FOR TERMINATION; Loss of confidence as a just cause for termination of employment is premised from the fact that an employee concerned holds a position of trust and confidence. However, the act complained of must be work-related such as would show the employee concerned to be unfit to continue working for the employer. FACTS: Petitioner Alejandro Y. Caoile was an Electronic Data Processing (EDP) Supervisor for private respondent Coca-Cola Bottlers Philippines Inc. (CCBPI) in its Zamboanga plant.A such supervisor, he was tasked to directly supervise the installation of the company’s housewiring project in the plant premises. For the said project, he contracted the services of a contractor. Since the project falls under his direct supervision, all cash advances by the contractor were coursed through him. He was later dismissed on the ground of loss of trust and confidence for his direct involvement in the anomalous encashment of check payments to such contractor. Contesting his dismissal, petitioner filed a complaint against CCBPI and its officers.for illegal dismissal and money claims. The NLRC ruled that the petitioner committed acts constituting a breach of trust and confidence reposed in him by his employer, thus, his dismissal is justified. ISSUE: Whether or not the dismissal is justified. HELD: The dismissal was justified. Loss of confidence as a just cause for termination of employment is premised from the fact that an employee concerned holds a position of trust and confidence. However, in order to constitute a just cause for dismissal, the act complained of must be work-related such as would show the employee concerned to be unfit to continue working for the employer. In the present case, petitioner is not an ordinary rank-and-file employee. He is the EDP Supervisor tasked to directly supervise the installation of the housewiring project in the company’s premises. He should have realized that such sensitive position requires the full trust and confidence of his employer. He ought to know that his job requires that he he keep the trust and confidence bestowed on him by his employer unsullied. Breaching that trust and confidence by pocketing money as “kickback” for himself in the course of the implementation of the project under his supervision could only mean dismissal from employment. [CaoIie vs. NLRC et al, G.R. No. 115491, November24, 1998--FIRST DlVISION; Quisumbing,J.] JOB CONTRACTING; In legitimate job contracting, there exists no employer-employee relation between the principal and the worker cupplied by a job contractor. The principal is considered employer of the job contractor’s employees only for the payment of wages but not for separation pay. FACTS: Petitioner PAL entered into a service agreement with Stellar, a domestic corporation engaged in the business of job contracting janitorial services. Pursuant to this agreement, Stellar hired workers to perform janitorial and maintenance services for PAL, to which Parenas and the 47 other private respondents belong. The latter’s works were under the supervision of Stellar’s supervisors/foremen and timekeepers. They were also furnished by Stellar with janitorial supplies such as vacuum cleaners and polishers. When said contract expired in 1990, PAL called for the bidding of its janitorial requirements. Subsequently PAL informed Stellar that the service agreement would not be renewed since janitorial services were bidded to other job contractors. Alleging that they were illegally dismissed, the private respondents filed with the NLRC complaints against PAL for illegal dismissal and for payment of separation pay. NLRC held PAL liable for the payment of separation pay. Hence this appeal. ISSUE: Whether or not PAL should be held liable for the payment of separation pay. HELD: It is evident that there was permissible job contracting for the entire duration of the employment of private respondents. In fact, Stellar claims that it fails under the definition of an independent job contractor. This being the case, employer— employee relationship never existed between PAL and private respondents. In legitimate job contracting, no employer-employee relation exists between the principal and the jdb contractor’s employees. The principal (PAL) is responsible to the job contractor’s employees only for the payment of wages and not separation pay. [Philippine Airlines lnc. vs. NLRC et a!, G.R. No. 125792, November 9, 1998 --First Division: Panganiban, J.] SEPARATION PAY; Failure of the employer to prove serious financial losses entitles the dismissed employees to separation pay. The separation pay is computed by considering as one whole year a fraction of at least six (6) months that the employee has worked. FACTS: Petitioner Philippine Tobacco Flue-Curing & Redrying Corporation claimed that due to serious business losses, its processing plant in BalintawaR, Metro Manila shall be closed and shall be transferred to Candon, llocos Sur. As a result, two groups of employees, namely; the Lubat group and the Luris group filed complaints against it. The Lubat group is composed of petitioner’s seasonal employees who were not rehired for 1994 tobacco season. At the start of that season, they were merely informed that their employment had been terminated at the end of 1993 season. They claimed that petitioner’s refusal to allow them to report for work without mention of any just or authorized cause constituted illegal dismissal. Thus, they prayed for separation pay, backwages, attorney’s fees and moral damages. On the other hand, the Luris group is made up of seasonal employees who worked during 1994 season. On August 3, 1994, they received a notice informing them that they were no longer allowed to work starting August 4,1994. Instead, petitioner awarded them separation pay computed based on the total number of days actually worked over the total number of working days in one year. In their complaint, they claimed that the computation should be based on the actual number of years served and not on the total number of working days in a year. ISSUE: Whether or not the seasonal employees who have worked for less than one year are entitled to separation pay. HELD: The petitioner was not able to prove serious financial losses to justify its non-payment of separation pay to its employees. It appears that the Statement of Income and Expenses submitted by petitioner was illogical and misleading because all of its selling, administrative and interest expenses for a given year was deducted from its earning in its tobacco sales given the fact that they are still engaged in other businesses such as corn and rental operations. The petitioner tried to persuade the Court that it had incurred no expenses at all in its other profit centers and that all of its expenses resulted from its tobacco processing and redrying operations. This is illogical, thus, the petitioner is liable to pay separation pay. The formula which petitioner used in computing the separation pay is both unfair and inapplicable. Although the Labor Code does not specifically define one year of servibe for purposes of computing separation pay, the same Code provides, however, in Arts. 283 and 284 that a fraction of at least six (6) months shall. be considered one whole year. Applying it to the c~se at bar, the amount of separation pay which respondent members of Lubat and Luris groups should receive is one-half (1/2) their respective average monthly pay during the last season they worked multiplied by the number of years they actually rendered service, provided that they worked for at least six (6) months during a given year. [Phil. Tobacco Flue-Curing and Redrying Corporation vs NLRC, GA. No. 127395, December 10, 1998---FIRST DIVIS!ON; Panganiban, J.] ILLEGAL DISMISSAL; Seasonal employees who are called to work from time to time and are temporarily laid off during off season are not separated from service in said period, but are merely considered on leave until re-employed. FACTS: Petitioner Philippine Tobacco Flue-Curing & Redrying Corporation claimed that due to serious business losses, its processing plant in Balintawak, Metro Manila shall be closed and shall be transferred to Candon, Ilocos Sur. As a result, two groups of employees, namely; the Lubat group and the Luris group filed complaints against it. The Lubat group is composed of petitioner’s seasonal employees who were not rehired for 1994 tobacco season. At the start of that season, they were merely informed that their employment had been terminated at the end of 1993 season. They claimed that petitioner’s refusal to allow them to report for work without mention of any just or authorized cause constituted illegal dismissal. Thus, they prayed for separation pay, backwages, attorney’s fees and moral damages. On the other hand, the Luris group is made up of seasonal employees who worked during 1994 season. On August 3, 1994, they received a notice informing them that they were no longer allowed to work starting August 4,1994. Instead, petitioner awarded them separation pay computed based on the total number of days actually worked over the total number of working days in one year. In their complaint, they claimed that the computation should be based on the actual number of years served and not on the total number of working days in a year. ISSUE: Whether or not the dismissal of the employees was valid. HELD: There was illegal dismissal when the petitioner refused to allow the members of the Lubat group to work during the 1994 season. Seasonal workers who are called to work from time to time and are temporarily laid off during off season are not separated from service in said period but are merely considered on leave until re-employed. Therefore it follows that the employer-employee relationship between herein petitiOner and members of the Lubat group was not terminated at the end of the 1993 season. From the end of the 1993 season until the beginning of the 1994 season, they were considered only on leave, but nevertheless still in the employ of petitioner. [Phil. Tobacco Flue-Curing and Redrying Corporation vs NLRC, GA. No. 127395, December 10, 1998---FIRST DIVIS!ON; Panganiban, J.] JURISDICTION OF LABOR ARBITERS; The existence of employer-employee relation betweenthe parties is a condition stiie qua non before the Labor Arbiter may assume jurisdiction over a case. No employer-employee relationship existed between a company and the security guards assigned to it by a security service contractor. FACTS: Petitioner Citibank and El Toro Security Agency entered into a contract whereby the latter would provide security and protective services to safeguard and protect the bank’s premises. Said contract expired and was not renewed. The petitioner then hired the services of another security agency to guard its premises. The Citibank Integrated Guards Labor Alliance (CIGLA) of which the security guards of El Toro were members considered the non-renewal of El Toro’s service agreement as constituting a lockout and or a mass dismissal. They threatened to go on strike against Citibank and picket its premises. Thus, the prospect of disruption of business operations, Citibarikfiled with the RTC a complaint for injunction and damages seeking to enjoin CIGLA from striking at the bank’s premises. CIGLA filed a motion to dismiss on the ground of lack of jurisdiction. It contends that there being a labor dispute, the jurisdiction over which lies in the labor tribunal. ISSUE: Whether or not it is the labor tribunal or the regional trial court that has jurisdiction over the subject matter of the complaint filed by Citibank. HELD: The Labor Arbiter has no jurisdiction over a claim filed where no employer-employee relationship exists between the parties. In the case at bar, there exists no employer-employee relationship between Citibank and the security guards who are members of the union because El Toro is an independent contractor. Hence, there was no labor dispute but only a civil one, that which involves Citibank and El Toro regarding the termination or non-renewal of the contract of services. Consequently, the case falls within the jurisdiction of the Regional Trial Court. [Citibank vs. CA and CIGLA, G.R. No. 108961, November27, 1998- Third Division: Pardo, J.] JURISDICTION OF NLRC; Decisions of Labor Arbiters allegedly rendered without jurisdiction cannot be impugned through a petition before the RTC but in the NLRC which has the exclusive appellate jurisdiction over such cases. FACTS: The Board of Directors of Air Services Cooperative cancelled and revoked Recarido Batican’s membership in the cooperative after the latter was found guilty of illegally draining aviation fuel from the aircraft. Batican filed before the NLRC a complaint for illegal dismissal and monetary claims. The Labor Arbiter ruled in favor of Batican. Petitioner Cooperative, instead of interposing an appeal to the NLRC, filed a Petition for Certiorari, Prohibition and Annulment of judgment before the RTC on the ground that the Labor Arbiter rendered the decision without jurisdiction over the subject matter. The trial court dismissed the petition for lack of jurisdiction. ISSUE: Whether or not a decision of Labor Arbiter allegedly rendered without jurisdiction may be annulled in a petition before the RTC. HELD: The answer is in the negative. Art. 223 of the Labor Code states that decisions, awards or orders of the Labor Axbiter are final and executory unless appealed to the Commission by any or both parties. Art. 227 of the same Code provides that NLRC shall have exclusive appellate jurisdiction over all cases decided by Labor Arbiters. It is clear therefrom that regular courts have no jurisdiction to hear and decide the petition filed by the petitioners. [Air Services Cooperative et at, vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 118693, July23, 1998---Third Division; Romero, J.] JURISDICTION OF DOLE; The Secretary of Labor is now empowered by RA 7730 to enforce compliance with labor standards law even if the amount of the employees’ monetary claim exceeds P5,000. The jurisdictional limitation imposed by Art. 128 and 129 of the Labor Code on the visitorial and enforcement power of the Secretary of Labor has been repealed by RA 7730. FACTS: A request was made for an investigation of petitioner Copylandias establishment, for violation of labor standards law. Inspections by the Secretary of Labor yielded the following violations such as underpayment of wages, underpayment of 13th month pay and non-grant of service incentive leaves with pay. The Regional Director ordered petitioner to pay the employees their backwages. In his appeal, petitioner argued that the Regional Director, under Art. 129 of the Labor Code, has no jurisdiction over the complaint since individual monetary claims of the employees exceed P5000.00. He alleged that the Regional Director should have indorsed the case to the Labor Arbiter for proper adjudication and for a more formal proceeding where there -is ample opportunity for him to present evidence to contest the claims of the employees. ISSUE: Whether or not the Regional Director has jurisdiction over the instant labor case. HELD: The contention of the petitioner, that the visitorial power of the Secretary of Labor to order andenforce compliance With labor standards laws cannot be exercised where the individual claim exceeds P5,000.00 can no longer be applied in view of the enactment of RA 7730 amending Art. 128 and 129 of the Labor Code. The enactment of RA 7730, on June 2,1994 strengthened the visitorial and enforcement powers of the Secretary of Labor to do away with the jurisdictional limitations imposed in the Servando case promulgated on June 5, 1991 and to finally settle any lingering doubts on such powers of the Secretary. This case overturns the Supreme Court ruling in the said Servando case. [Guico, Jr. vs. Sec. of Labor, G.R. No. 131750, November 16, 1998 ---SECOND DIVISION; Puno, J.] DISMISSAL; Mere participation of union members in an illegal strike is not a sbfficient ground for their termination. FACTS: A strike was staged by CCBPI Postmix Workers Union due to bargaining deadlock with regard to the renewal of the CBA. The Labor Arbiter ruled that the strike was valid but on appeal, NLRC reversed that decision. Consequently, the company terminated the services of eight employees who were believed to be officers of the union. It alleged that by being signatories to the CBA, Memorandum and Amendments, said employees have effectively represented themselves as union officers. Hence, having participated in an illegal strike, their dismissal was proper. ISSUE: Whether or not the employees who were believed to be officers of the union were rightfully dismissed from service as a consequence of their participation during the strike. HELD: The answer must be in the negative. The effects of illegal strikes, as outlined in Art. 264 of the Labor Code, make a distinction between ordinary workers and union officers who participated therein. Under established jurisprudence, a union officer may be terminated from the employment for knowingly participating in an illegal strike. The fate of union members is different. Mere participation in an illegal strike is not a sufficient ground for their termination, provided that they did not commit illegal acts during the said strike. In the case at bar, the said employees are merely union members and not union officers. Being signatories to the CBA, Memorandum and Amendments written after the strike did not sufficiently establish the status of the employees as union officers during the illegal strike. The said employees signed the documents only as witnesses to the contracts to attest to the facts that the documents were indeed signed and that the CBA was validly renewed. [CCBPI Postmix Workers Union vs. NLRC and CCBPI, G.R. No. 114521, CCBPI vs. NLRC et at, G.R. No. 123491, November27, 1998—-First Division, Quisumbing, J.] RIGHT OF LEGITIMATE LABOR ORGANIZATION; The legitimate labor organization has the right to file a case in the name of the members but the Individual members are not precluded to file a case in their own name or withdraw therefrom and file another in their own names. Absent any withdraWal by the union members, they are bound by the decision against the union and sufficient to constitute res judicata. FACTS: Respondent company AG&P temporarily laid off forty percent (40%) of its employees, upon claim of severe financial losses due to adverse business conditions. This situation forced herein petitioner URFA, then the recognized and exclusive collective bargaining agent for all regular and rank and file employees of AG&P, to conduct a strike. To end the strike, AG&P and its unions reached an agreement that the company will extend financial a~sistance to all laid-off employees during the lay off period. Petitioners Aldovino and Pimentel who were members in good standing of said union and among the laid-off employees, received temporary financial assistance. Four months thereafter, the Voluntary Arbitrator upheld the lay off as duly substantiated. No appeal was filed. Years later, petitioners filed a separate but similar complaints against AG&P for illegal layoff and illegal dismissal, among others. The Labor Arbiter, finding merit in such complaints, ordered AG&P to reinstate the petitioners. AG&P appealed to the NLRC protesting that the issue of the validity of the temporary layoff had already been decided in its favor, hence res judicata. The NLRC agreed with AG&P. Petitioners insisted that res judicata will not apply because the last requisite of identity of parties, subject matter and causes of action is lacking in the instant case. ISSUE: Whether or not the princple of res judicata will apply. HELD: Petitioners are now barred by prior judgment from raising in their case the same issue of the legality of their lay offs. There is no doubt that there is identity of parties in the arbitrated case by URPA and that filed by the petitioners. In the case at bar, since it has not been shown that Aldovino and Pimentel withdrew from the case undergoing voluntary arbitration, it stands to reason that both are bound by the decision rendered thereon and which was not appealed by the union. [Aldovino vs. NLRC, G.R. No. 121189, November 16, 1998] GRANT OF BACKWAGES; An illegally dismissed employee is entitled to backwages notwithstanding his failure to claim for such in his complaint. FACTS: Petitioner de Ia Cruz was employed by respondent Lo as chief patron (captain) in one of his fishing boats. It appears that the petitioner is the one who decides when to sail out to the sea, where to fish, how long will they be fishing and when to go back to the port. Thus, he was deemed to be performing the tasks of a managerial employee. Subsequently, however, he was dismissed by the respondent. He filed a complaint for illegal dismissal and prayed forthe payment of underpaid salary; overtime pay, legal holiday pay, premium pay for holiday and rest day, and payment of commission and separation pay. He, however, failed co claim for back-wages in such complainf The Labor Arbiter ruled that he was illegally dismissed and granted his prayer as to the separation pay but dismissed all other claims. An appeal to the NLRC was dismissed for lack of merit holding that petitioner is not entitled to backwages because he failed to specifically claim for such backwages in his complaint. ISSUE: Whether or not the NLRC acted correctly when it dismissed petitioner’s claim for backwages and other allowances prayed for in the complaint. HELD: Grave abuse of discretion attended the refusal of the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC to award backwages to petitioner, simply because petitioner did not ask for such relief in his complaint. Since both the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC concluded that pet.tioner was illegally dismissed, he should be granted payment of backwages notwithstanding his failure to claim for the same in his complaint. Under Article 279 of the Labor Code, an employee who is unjustly dismissed from work shall be entitled to reinstatement and backwages. As to the other reliefs prayed for, the Labor Arbiter was correct in holding that petitioner was not entitled to overtime pay, legal holiday pay, premium pay for holidays and restdays since the petitioner is an employee who falls squarely within the category of “officers or members of a managerial staff” who under Art. 82 of the Labor Code are not entitled to such benefits. [DeIa Cruz vs NLRC, G.R. No. 121288, November20, 1998 ---FIRST DIVISION; Davide, Jr. ] CERTIFICATION ELECTION; Supervisory and rank-and-file employees cannot be represented by a single labor organization. FACTS: Respondent union Dunlop Slazenger Staff Association-APSOTEU filed a petition for certification election before the Department of Labor and Employment a duly registered legitimate labor organization. It alleged that the petitioner company is not unionized establishment and there is no collective bargaining agreement that will ban the filing of certification election. Also, no certification of election has been conducted within one year prior to filing of its petition for certification election. The petitioner Dunlop SIazenger (Phil.),. Inc, moved to dismiss the petition on ground that the respondent union is comprised of supervisory and rank-and-file employees and can not act as bargaining agent for the proposed unit and that a single ceIrtiticatiQfl election can not be conducted jointly among supervisory and rank and fiIe employees. The petition of the association was granted by the mediator arbiter and was affirmed by the Secretary of Labor. Herein, petitioner company filed a motion for reconsideration which. was denied by the Secretary of Labor. ISSUE: Whether or not the respondent union can file a petition for certification election to represent the supervisory and rank-and-file employees of the petitioner company. HELD: Respondent union has no legal right to file:certificatiori election to represent a bargaining unit’ composed of supervisors for so long as it consists rank-and-file employees amongit~ members. Article 245 of Labor Code states that a labor organization composed of both rank-and-file and supervisory employees is no. labor organization. Not being one, it can not possess any of the rights of a legitimate labor organization, including the right to file a petition for certification electiort for the purpose of collective bargaining. .., Supervisors can be an appropriate bargaining unit, being a group of employees who have substantial, mutual interest irtwages, hours’ of work, working conditions and other subjects of collective bargaining. However, supervisorsand rank~and-fiIe empk~Iees c~h not be’ represented by a single labor organization. [Dunlop Slazenger (Phil.), Inc. vs. Hon. Secretary of Labor and Employment and Dunlop Slazenger Staff Association-AP-SOTEU, G.R. No. 131248, December 11, 1998---SECOND DIVISION, Bellosillo, J.] DUE PROCESS; A plea of denial of procedural due process cannot be entertained when he who -makes the plea is effectively given the opportunity to be heard. FACTS: Estilo sued petitioner Pepsi Cola Bottling Philippines Inc. before the Regional Arbitration of NLRC. He charged the beverage firm with illegal dismissal as well as underpayment of wage, 13 th month pay, Overtime pay, premium pay for holidays and rest days and commission, and additionally sought to recover moral damages, attorney’s fees and other benefits. The labor arbiter issued an order directing the parties to’submit their ppsition. papers within 20 days from receipt~of the order. The petitioner company complied with the order controverting the allegations and various claims of Estilo. The latter did not submit any paper. One year thereafter, the labor arbiter rendered a decision dismissing Estilo’s complaint. On appeal, the NLRC ruled that there was denial of procedural due process. Petition. ISSUE: Whether or not there was denial of procedural due process. HELD: The records easily substantiate the fact that Estilo has been duly accorded an opportunity to submit his position paper in the proceedings before the Regional Arbitration Branch. Nonetheless, Estilo failed to submit his memoranda. It is a noted rule that a plea of denial of procedural due process, where the defect consists in the failure to furnish an opponent with a copy of a party’s position paper, cannot be entertained wheh he who makes the plea is effectively given the opportunity to be heard in a Memoranda of Appeal. Estilo was the complainant in this case and in him rested the primary burden~of proving his claim. [Pepsi Cola vs NLRC: GR. No. 127529; December 10, 1998 First Division Vitug J.] RECRUITMENT AND PLACEMENT; Any person or entity who or which offers or promises for a fee employment to two or more persons shall be deemed engaged in recruitment and placement. FACTS: Umblas, Jimenez, Escano and Ventula applied for employment overseas with MZ Ganaden Consultancy Services allegedly owned by the accused spouses Felipe and Myrna Ganaden, spouses Gerry and Emma Ganaden and Polly Guillermo. They were asked to pay placement fees in consideration of Ganaden’s promise to facilitate their employment overseas. The plaintiffs flew to Singapore where they waited for their job placements. Giving up hope of employment, all of them eventually returned to the Philippines. Upon arrival, they asked the accused-appellant Felipe Ganaden to return their money and reimburse them for their expenses which the latter refused. MZ Ganaden Consultancy Service was discovered to have neither authority nor license to recruit workers for deployment abroad. An illegal recruitment case was filed against Ganaden. Upon conviction, accused appellant maintains that his dealings with complainants consisted only in helping them facilitate the issuance of their travel documents for the purpose of travelling as tourists. ISSUE: Whether or not the accused-appellant is engaged in recruitment and placement as to render illegal its recruitment activities without the necessary license. HELD: The acts of accused appellant consisting of his promise of employment to complainants and of transporting them abroad fall squarely within the ambit of recruitment and placement as defined in Article 13, par. (b) of the Labor Code. Consequently, the Labor Code renders illegal all recruitment activities without the necessary license or authority from the POEA. [People vs Ganaden, G. R. No. 125441, November 27, 1998 FIRST DIVISION; BelIosiIIo J.] - ECONOMIC SABOTAGE; Illegal recruitment committed in large scale Is an offense involving economic sabotage. FACTS: Umblas, Jimenez, Escano and Ventula applied for employment overseas with MZ Ganaden Consultancy Services. They were asked to pay placement fees in consideration of Ganaden’s promise to facilitate their employment overseas. The plaintiffs flew to Singapore where they waited for their job placements. Giving up hope of employment, all of them eventually returned to the Philippines. Upon arrival, they asked the accused-appellant Felipe Ganaden to return their money and reimburse them for their expenses which the latter refused. MZ Ganaden Consultancy Service was discovered to have neither authority nor license to recruit workers for deployment abroad. The accused appellant was charged with illegal recruitment in large scale constituting economic sabotage for which he was found guilty. ISSUE: Whether or not the offense committed constitutes economic sabotage. HELD: Ganaden committed illegal recruitment in large scale, thus, involving economic sabotage. If the illegal recruitment is committed by a syndicate or in large scale, the Labor Code considers it an offense involving economic sabotage. Illegal recruitment in large scale is committed when a person a) undertakes any recruitment activity defined under Art. 13, par (b) or any prohibited practice enumerated under Art. 34 of the Labor Code; b) does not have a license or authority to lawfully engage in the recruitment and placement of workers; and c). commits the same against three or more persons. [People vs. Ganaden, G. R. No. 125441, November27, 1998 FIRST DIVISION; BelIosiIIo, J] - TECHNICALITIES NOT BINDING IN LABOR CASES; Rules of procedure and evidence should not be applied in a very rigid and technical sense in labor cases. FACTS: Florentino Lamsen is a security guard of petitioner security agency who filed a complaint for underpayment of wages and overtime pay against the latter. The security agency moved to dismiss the complaint asserting that it had no factual basis and it submitted photocopies of a random sampling of Lamsen’s payrolls in support thereof. The Labor Arbiter ruled in favor of Lamsen. Upon appeal, the NLRC questioned the authenticity of the photocopies of payrolls but denied the agency the opportunity to present the original copies of said documents to show full payment of salaries and overtime pay. NLRC affirmed the Labor Arbiter but modified the monetary award. ISSUE: Whether or not NLRC committed grave abuse of discretion in depriving petitioners the opportunity to submit additional evidence. HELD: NLRC committed grave .abuse of discretion by strictly applying procedural technicalities in the case before it in corriplete disregard of established policy of the Labor Code and jurisprudence. The Supreme Court upholds the power of the NLRC to consider even on appeal such other and additional documentary evidence from the parties if only to support their contentions. This is in accord with the well-settled doctrine that technicality should not be allowed to stand in the way of eqtfitably and completely resolving the rights and obligations of the parties. [Philippine Scout Veterans Security and Investigation Agency, Inc~ vs. NLRC, G. R. No. 124500, December 4 1998- FIRST DIVISION; Davide, J.] DISEASE OR ILLNESS AS GROUND FOR TERMINATION; A certification by competent public health authority is needed before an employee can be dismissed on ground of illness or disease. FACTS: Osdana was recruited by petitioner Triple Eight Integrated Services, Inc., for employment in a firm based in Saudi Arabia as food server. Osdana left for Saudi Arabia and commenced working but she was made to perform tasks which were unrelated to her job designation contrary to the terms and conditions of the employment contract. By reason of which, she was hospitalized and underwent two surgical operations. After the second operation, she was dismissed from work on ground of illness. A complaint was filed before the Labor Arbiter against petitioner praying for unpaid and underpaid salaries and for damages. The Labor Arbiter ruled that Osdana was illegally dismissed. NLRC upheld the decision of the Labor Arbiter. Petitioner filed a petition for certiorari. ISSUE: Whether or not Osdana was validly dismissed on the ground of illness. HELD: Osdana was illegally dismissed. Where the employee suffers from disease, and his continued employment is prohibited by law, the employer shall not terminate his employment unless there is a certification by competent public health authority that the disease cannot be cured within 6 months. If the disease can be cured within the period, the employer shall not terminate the employee but shall ask the employee to take a leave. Osdanas continued employment was not prohibited by law and her illness is not a contagious disease. Moreover, petitioner has not presented any medical certificate in support of its claim that Osdana was ill and could not anymore perform her work.. The requirement for medical certificate~cannot be dispensed with. Otherwise, it would sanctiOn the arbitrary determination by the employer of the gravity or extent of the employees’ illness and thus defeat the public policy on protection of labor. [Triple Eight lntegrated Services, Inc. vs NLRC, G. R. No. 129584, December 3, 1998 THIRD DIVISION; Romero~ J.] - RETIREMENT BENEFITS UNDER CBA; Employer-employee relationship still exists despite the employee’s retirement for the purpose of prosecuting the latter’s claim for retirement benefits under the CBA. FACTS: Employees of Producers Bank of the Philippines who have retired, claim benefit under their CBA retirement scheme. The bank denied the claim stating that there no longer existed an employer-employee relationship due to the retirement of said employees. ISSUE: Whether or not the employees are entitled to the retirement benefits under the CBA. HELD: The bank’s contention is untenable. The very essence of retirement is the termination of employer-employee relationship, but it does not, in itself, affect the status of employment especially when it involves all rights and benefits due to an employee. The retirement scheme was part of the employment package which works to release the employee from the burden of worrying for his financial support, and is a form of reward for his loyalty. When the employee requests for his retirement benefits under the CBA, he is, thus, merely demanding for his right. Employer-employee relationship still exists for this purpose. [Producers Bank of the Philippines vs. NLRC, G. R. No. 118069, November 16, 1998 THIRD DIVISION; Narvasa, C. J.] - ILLEGAL DISMISSAL; A mere accusation of wrongdoing or a mere pronouncement of lack of confidence is not sufficient cause for a valid dismissal of an employee. FACTS: Petitioner Serafin Quebec, Sr. was the owner of the Canhagimet Express, a transportation company before it was sold. In September 1981, respondent Antonio, brother of petitioner, was hired by the company as inspector and liaison officer with the powers and duties of a supervisor/manager. In 1991, the latter was dismissed without notice and hearing by the wife of the petitioner on suspicion of covering up the womanizing activities of Serafin and that the petitioner suspected him of misappropriating Canhagimet funds by the mere fact that he was unable to explain his wherewithal to buy a house and lot in a short time. Meanwhile, on November 5,1981, private respondent Pamfilo Pombo, Sr. was hired as driver-mechanic and co-manager of Antonio in Catbalogan. In 1990, he was dismissed without notice and hearing on the ground of non-payment of freightage at the Canhagimet buses in transporting his rattan and stalagmites, and his inability to help in the repair of a bus. They both filed a case for illegal dismissal which were later on consolidated. The labor arbiter ruled in favor of the petitioner alleging that the dismissal was valid since an employee could be terminated from employment for lack of confidence due to serious misconduct. Feeling aggrieved, the respondents went to NLRC which reversed the decision of the labor arbiter. Hence, this appeal by the petitioner. ISSUE:Whether or not respondents were illegally dismissed. HELD: Respondents were illegally dismissed. Basic is the rule that when there is no showing of a clear, valid and legal cause for the termination of employment, the law considers the matter a case of illegal dismissal and the burden is on the employer to prove that the termination was for a valid or authorized cause. This burden of proof appropriately lies on the shoulders of the employer and not on the employee because a worker’s job has some of the characteristics of property rights and is therefore within the constitutional mantle of protection. In the case at bar, the contentions of the petitioner were never substantiated by any evidence other than the barefaced allegations in the affidavits of petitioner and his witnesses, aside from the fact that there was the absence of notice and hearing. Hence, a mere accusation of wrongdoing or a mere pronouncement of lack of confidence is not sufficient cause for a valid dismissal of an employee, [Quebec, Sr. vs. NLRC, G.R. No. 123184; January 22, 1999; BeIIosillo, J.] ILLEGAL DISMISSAL; Where the consequences of the act did not directly affect the business of petitioner or the atmosphere in the work premises, such act does not warrant the penalty of dismissal. FACTS: Respondent Diosdado Lauz started employment with petitioner Solvic Industrial Corporation in 1977. He has never been suspended or reprimanded but in 1994, he was terminated from service. The termination of respondent arose from the incident where respondent confronted Foreman Carlos Aberin, thereafter striking him on the shoulder beside the neck with a bladed weapon inflicting bodily injury on him in the process. That several days after said incident, respondent did not report for work, hence, was issued a memorandum of preventive suspension. Thereafter, a series of administrative investigation was conducted, where respondent refused to give any further statement or explanation. However, in a meeting held with the union officers by Carlos Aberin and Diosdado Lauz, the latter admitted attempting to take the life of Mr. Aberin and apologized for the same. Subsequently, he was served his letter of termination which he refused to receive. ISSUE: Whether or not the acts of private respondent are so serious as to warrant the penalty of dismissal. HELD: The acts of private respondent are not so serious as to warrant the extreme penalty of dismissal. Private respondent was accused of hitting the victim once with the blunt side of a bob. Private respondent could have attacked him with the blade of the weapon, and he could have struck him several times. But he did not, thus negating any intent on his part to inflict fatal injuries. In fact, the victim merely sustained a minor abrasion and has since forgiven and reconciled with the private respondent. If the party most aggrieved namely, the foreman has already forgiven the private respondent, then petitioner cannot be more harsh and condemning than the victim. Besides, no criminal or civil action has been instituted against private respondent. Furthermore, in his twenty years of service in the company, he has not been charged with any similar misconduct. Furthermore, its consequences did not directly affect the business of petitioner or the atmosphere in the work premises. [Solvic Industrial Corporation, el at vs. NLRC, G.R. No. 125548, September 25, 19998; Panganiban, J.] — — DISMISSAL; Termination of employment on ground of loss of trust and confidence does not require proof beyond reasonable doubt of the employee’s misconduct. It is sufficient that there is some basis for the loss of trust or that the employer has reasonable ground to believe that the employee is responsible for the misconduct whieh renders him unworthy of the trust and confidence demanded by his position. FACTS: Petitioner Patrick Del Val was employed by the respondent hotel as assistant manager and concurrent night shift manager. In a meeting with the resident general manager of the hotel, he was confronted about reports/ complaints received from employees against him. On the same day, a memorandum was issued requiring him to explain within 48 hours the alleged violations of their House Code of Discipline regarding uttering words and doing acts to a superior which are manifestly insulting and grossly disrespectful to the latter; and for falsifying the time records in such a way as to mislead the user thereof. Del Val failed to respond, until another memorandum was issued requiring Del Val to explain another alleged violations of the company House Code of Discipline, particularly, reporting for work while under the influence of liquor and for sleeping while on duty. Meanwhile, Del Val was suspended for 15 days and after said suspension, he was refused work. He filed a complaint for illegal suspension, illegal dismissal, unpaid salary and damages against respondent hotel. He alleged that his dismissal was without cause and prior due process. The Labor Arbiter ruled that the suspension and dismissal of petitioner is illegal and ordered for reinstatement with backwages. Respondent hotel appealed to the NLRC, which modified the judgment of the Labor Arbiter. NLRC upheld that the petitioner was illegally suspended, however, it held that the petitioner was validly dismissed for loss of trust and confidence although not accorded due process. ISSUE:Whether or not the dismissal is for just cause on the ground of loss of trust and confidence. HELD: The dismissal was valid. Article 282 (c) of the Labor Code provides that an employer may terminate an employment for willful breach by the employee of the trust reposed in him by his employer. Pursuant to the cited provision, boss of confidence should arise from particular proven facts. Termination of employment on this ground does not require proof beyond reasonable doubt of the employee’s misconduct. It is sufficient that there is some basis for the loss of trust or that the employer has reasonable ground to believe that the employee is responsible for the misconduct which renders him unworthy of the trust and confidence demanded by his position. As the Assistant Manager of the hotel, petitioner is tasked to perform key and sensitive functions, and thus bound by more exacting work ethics. He should have realized that such sensitive position requires the full trust and confidence of his employer in every exercise of managerial discretion insofar as the conduct of his employer’s business is concerned. The dismissal was affirmed but the respondent is required to pay indemnity to petitioner for breach of legal procedure prior to termination. [Patrick Del VaI vs. NLRC, G.R. No. 121806, September 25, 1998; Davide, Jr. Chaimian]. DISMISSAL; In order that an employer may terminate an employee on the ground of willful disobedience to the former’s orders, regulations or instructions, it must be established that said orders, regulations or instructions are (a) reasonable and lawful, (b) sufficiently known to the employee, and (c) in connection with the duties which the employee has been engaged to discharge. FACTS: Petitioner Anita Salavarria was employed by respondent Colegio de San Juan de Letran as a high school teacher for nine (9) years from 1982 to 1991. During her tenure as a teacher, she had been meted out a two-week suspension in 1988 for having solicited contributions without the requisite school approval with a final warning that commission of a similar offense shall warrant the imposition of a more severe penalty. In 1991, her second year students requested her if they could initiate a special project in lieu of the submission of the required term papers. The students explained that the project consisted in collecting contributions from each Of them to purchase religious articles to be distributed among the several churches in Metro Manila and nearby rural areas. Furthermore, they claimed that doing the project is in consonance with their lesson on love of God and neighbor and that the activity would entail a much lesser expense than the completion of the term papers. After continuous proddings, she was prevailed upon to accede to the students’ proposal. Before the project was executed, petitioner Salavarria received a memorandum directing her to explain why she should not be disciplined for violation of a school policy against illegal collections from students. She replied denying having initiated the project and arguing that her participation was merely limited to approving the project such that she could not have transgressed any school policy. In spite of her written explanation and the High School Council’s recommendation of one-month suspension, she was terminated from the service. She filed a complaint for illegal dismissal. She contended that the dismissal was arbitrarily carried out since the solicitation was initiated by the students and that she never misappropriated the money collected but instead returned to the student-leaders for proper reimbursement to the students concerned. The Labor Arbiter ruled in her favor but the NLRC reversed the decision. ISSUE:Whether or not the dismissal is proper. HELD: The dismissal is valid since it was effected with a just cause based on employee’s willful disobedience Of employer’s orders, regulations or instructions. In order that an employer may terminate an employee on the ground of willful disobedience to the former’s orders, regulations or instructions, it must be established that said orders, regulations or instructions are (a) reasonable and lawful, (b) sufficiently known to the employee, and (c) in connection with the duties which the employee has been engaged to discharge. If there is one person more knowledgeable of the school’s policy against illegal exactions from students, it would be petitioner Salavarria. Regardless of who initiated the collections, the fact that the same was approved or indorsed by petitioner, made her “in effect the author of the project.” Having been administratively penalized for a similar offense in 1988, she should have been more circumspect in her actuations of such nature. [Anita SaIavarria vs. Letran College, G.R. No. 110396, September 25, 1998; Romero, J.] DISMISSAL; It is not within the province of an investigating body to decide the penalty to be imposed upon those employees found guilty since this discretion is vested in the employer. FACTS: Petitioner Anita Salavarria was employed by respondent Colegio de San Juan de Letran as a high school teacher for nine (9) years. In 1991, after much proddings by the students, she approved of their request to collect funds from each of them to finance a special project in lieu of making term papers. The students explained that the contributions would be used to purchase religious articles for distribution among the several churches in Metro Manila and nearby rural areas. Furthermore, they claimed that doing the project is in consonance with their lesson on love of God and neighbor and that the activity would entail a much lesser expense than the completion Qf the term papers. She was summoned by the administration to explain why she should not be disciplined for violation of a school policy against illegal collections from students. It appeared that she had been meted out a two-week suspension in 1988 for having solicited contributions without the requisite school approval with a final warning that commission of a similar offense shall warrant the imposition of a more severe penalty. The High School Council recommended a one-month suspension but the administration terminated her from the service. She filed a complaint for illegal dismissal. She questioned the wisdom of her outright dismissal by the school when the latter ignored the High School Council’s recommendation that she be penalized by a month’s suspension. The Labor Arbiter ruled in her favor but the.NLRC reversed the decision. ISSUE: Whether or not the recommendation of an investigating body is binding on the superior. HELD: The function of the Council is merely recommendatory. It is limited to the investigation of cases involving violation by faculty and students alike of schOol rules and regulations, and the submission of its findings and recommendations thereon. It is not in the council’s province to finally decide what penalty is to be imposed upon those found guilty since this discretion is vested in the school head. [Anita Salavarria vs. Letran College, G.R. No. 110396, September25, 1998; Romero, J.] SEPARATION PAY IN LIEU OF REINSTATEMENT; An employee who is unlustly dismissed from work is entitled to reinstatement. However in instances where reinstatement is not a viable remedy due to severely strained relationship between the employer and the employee, separation pay shall be granted as an option to reinstatement. FACTS: Petitioner Melody Lopez was employed by respondent Letran College Manila from 1979 to 1991. While holding the position of guidance counselor of the elementary department, she was able to organize career orientation for elementary students which garnered objections from other factions of the school. She wrote letters to school authorities regarding her problem and her feeling that conspiracy had set in to make her resign. She also received several memoranda requiring her to explain her actions which were unrelated to her work. Reports unknown to her surfaced in her 201 file containing complaints against her. She was later replaced as Elementary Guidance Counselor and was given the position of Head Psychometrician whose responsibility is to supervise tests given to all departments of the school. She was however not allowed to assist in giving tests in the elementary department and was even offered a sizable amount of money in exchange for her voluntary resignation but she refused. On February 16, 1991, the complainant got involved in an incident where she interceded for an employee of the Guidance Counseling Office who was refused to be given the key to the said office by respondent Fr. Lao. Respondents claimed that complainant uttered indecent and obscene remarks against Fr. Lao while Ms. Lopez denied such accusations and in turn accused Fr. Lao for embarrassing and humiliating her. As a result, the complainant was suspended for thirty days and she then fi!ed a complaint with the Arbiter of the Commission for illegal suspension. An Ad Hoc Committee was formed to look into the charges against her. The respondent gave notice of dismissal from employment of the complainant on grounds of serious misconduct, commission of a crime (grave oral defamation), insubordination, unfaithfulness to employer’s interest, quarrelling and challenging to a fight and loss of confidence. The complainant then filed a Motion to amend her complaint of illegal suspension to illegal dismissal. The Labor Arbiter found that the dismissal was for a just cause and with due process. On appeal, however, the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) reversed the decision and ruled that there was illegal dismissal due to absence of just cause and due process but ordered private respondent to grant separation pay in lieu of reinstatement. Petitioner elevated the case by petition for certiorari, seeking reinstatement to her former position without loss of seniority rights and payment of backwages including damages and attorney’s fees. ISSUES: Whether or not the dismissal is legal; whether or not a finding of illegal dismissal ipso facto results in reinstatement of the employee. HELD: The respondent school failed to establish clear and valid cause of termination thus the dismissal is considered illegal. The incident of February 16,1991 is unrelated to the work of complainant as Head Psychometrician of the school for she merely interceded for another employee. Infractions against her which surfaced in her 201 file can not be taken as justification for dismissal from service. Despite afinding of illegal dismissal against private respondent school, petitioner should not be reinstated. Generally, the remedy for illegal dismissal is the reinstatement of the employee to her former position without loss of seniority rights and the payment of backwages. However, there are instances as when reinstatement is not a viable remedy as where- as in this case-the relation between the employer and the employee had been severely strained that is not advisable to grant reinstatement. Since reinstatement would not be to the best interest of the parties, in lieu thereof, the NLRC correctly awarded separation pay to the complainant. [Lopez vs. NLRC, et al, G.R. No. 124548, October 8, 1998; Regalado, J.] GRANT OF SEPARATION PAY DESPITE VALID DISMISSAL; As a rule, an employee who is dismissed for cause is not entitled to any financial assistance except on equity considerations, separation pay shall be allowed as a measure of social justice only in those instances where the employee is validly dismissed for causes other than serious misconduct or those reflecting on his moral character. FACTS: Petitioner Anita Salavarria was employed by respondent Colegio de San Juan de Letran as a high school teacher for nine (9) years. In 1991, she was dismissed from the service after she approved the students’ request to collect contributions in lieu of making term papers. She approved the project after much proddings and insuring that the amounts collected would be used to purchase religious articles for distribution among the several churches in Metro Manila and nearby rural areas. However, her record showed that she had been meted out a two-week suspension in 1988 for having solicited contributions without the requisite school approval with a final warning that commission of a similar offense shall warrant the imposition of a more severe penalty. She filed a complaint for illegal dismissal. The Labor Arbiter decided in her favor but the NLRC ruled that the dismissal is proper but awarded her separation pay. ISSUE:Whether or not the award of separation pay is proper despite the validity of the dismissal. HELD: As a general rule, an employee who is dismissed for cause is not entitled to any financial assistance. However, equity considerations provide an exception. The grant of separation pay is not based merely on equity but on the provisions of the Constitution regarding the promotion of social justice and protection of the rights of the workers. Separation pay shall be allowed as a measure of social justice only in those instances where the employee is validly dismissed for causes other than serious misconduct or those reflecting on his moral character. In the case at bar, petitioner’s infraction of the school policy neither amounted to serious misconduct nor reflected that of a morally depraved person as may warrant the denial of separation pay to her. What justifies such liberal attitude of the court towards petitioner is that she never took physical custody of the funds, nor was she charged with misappropriating the same for personal gain. Also, considering that she had spent nine(9) years of her teaching career with Letran, the ends of social and compassionate justice would be served if she will be given some equitable relief. [Anita Salavarria vs. Letran College, G.R. No. 110396, September25, 1998; Romero, J.] CUMULATIVE RELIEFS IN ILLEGAL DISMISSAL; Both reliefs of reinstatement and full backwages are available to the illegally dismissed employees as a matter of course. However, if reinstatement is not possible, the employees are entitled to the cumulative reliefs of separation pay and full backwages. FACTS: Petitioner Lopez was employed as guidance counselor of the elementary department by private respondent Letran College Manila for thirteen (13) years before she was assigned as head psychometrician. She was a victim of conspiracy of harassment, intimidation and persecution by her co-employees and by the administration. Several unsavory reports appeared in her employment file without her being allowed to defend her sUe. Later, she was suspended for allegedly uttering indecent and obscene remarks against the respondent priest who is a member of the school administration. She was thereafter dismissed upon the recommendation of an ad hoc committee formed to look into the charges against her. She first filed a complaint for illegal suspension but she amended it to illegal dismissal. The labor arbiter ruled that the dismissal was for just cause and with due process but ordered payment of separation pay. On appeal, the NLRC ruled that there was illegal dismissal due to the absence of just cause and due process but ordered private respondent to grant petitioner separation pay in lieu of reinstatement. She appealed questioning the ruling of the NLRC in awarding separation pay in lieu of reinstatement despite a finding of illegal dismissal. She also seeks payment of backwages, allowances and other benefits from the time of illegal dismissal until her actual reinstatement. ISSUE:Whether or not petitioner is ipso facto entitled to reinstatement and full backwages if there is a finding of illegal dismissal. HELD: Both reliefs of reinstatement and full backwages are available to the illegally dismissed employees as a matter of course. However, if reinstatement is not possible, the employees are entitled to the cumulative remedy of separation pay and full backwages. In the case at bar, reinstatement would not be to the best interest of the parties due to the strained relations between the parties brought about by the litigation and the personal animosities that have been generated due to the attendayt circumstances of the case. In lie of reinstatement, she is entitled to payment of separation pay. [Melody Paulino Lopez V. NLRC, G.R.No. 724548, October 8,1999; Martinez, J.] BACKWAGES; Illegally dismissed employees after March 21,1989 are entitled to full backwages from the time of dismissal up to the time of actual reinstatement. By the term “full backwages”, It means without deducting from backwages the earnings derived elsewhere by the concerned employee during the period of his illegal dismissal. FACTS: Petitioner Lopez was employed as guidance counselor of the elementary department by private respondent Letran College Manila for thirteen (13) years. She was ordered replaced as guidance counselor and was assigned head psychometrician. In 1991, she was dismissed based on an incident where she allegedly uttered indecent and obscene remarks against the respondent priest who is a member of the school administration. The unsavory reports appearing in her employment file were also used against her despite the fact that she was allowed to explain the charges surfacing therein. As a consequence, she was placed under preventive suspension for thirty (30) days. She was thereafter dismissed upon the recommendation of an ad hoc committee formed to look into the charges against her. She first filed a complaint for illegal suspension but she amended it to illegal dismissal. The labor arbiter ruled that the dismissal was for just cause and with due process but ordered payment of separation pay. On appeal, the NLRC ruled that there was illegal dismissal but ordered private respondent to grant petitioner separation pay in lieu of reinstatement plus payment of back-wages. The Solicitor General is of the opinion that in computing backwages, the total amount derived from employment elsewhere by the employee from the date of dismjssal up to the date of reinstatement, if any should be deducted therefrom. ISSUE: Whether or not the contention of the SolGen is proper. HELD: The stance of the SolGen is erroneous. With regard to illegal dismissals effected after March 21, 1989, the illegally dismissed employee is entitled to full backwages from the time his compensation was withheld from him (which as a rule, is from the time of his illegal dismissal) up to the time of his actual reinstatement. By the term “full backwages”, it means without deducting from backwages the earnings derived elsewhere by the concerned employee during the period of his illegal dismissal. Since the dismissal as effected on May 1991, which is after March 21, 1989, Lopez should he entitled to payment of full backwages without deduction. [Melody Paulino Lopez v. NLRC, G.R .No. 124548, October 8,1999; Martinez, J.] PROBATIONARY EMPLOYMENT; Probationary employees, notwithstanding their limited tenure, are also entitled to security of tenure and they cannot be terminated except for just cause as provided by the Labor Code or under an employment contract. FACTS: Private respondent Victoria Abril was employed in 1982 by petitioner Philippine Federation of Credit Cooperatives, Inc. (PFCCI) in different capacities until 1988. Respondent subsequently went on leave when she gave birth. Upon her return, she discovered that another employee had been permanently appointed to her former position. She, nevertheless, accepted the position of Regional Field Officer under a contract which stipulated that employment status shall be for a probationary period of six (6) months. After said period had elapsed, respondent was allowed to work until the petitioner presented to her another employment contract for a period of one year, after which period her employment was terminated. , She filed a complaint for illegal dismissal against PFCCI. The company argued that the dismissal is valid because being a casual or contractual employee, she is dismissed after the termination of the project. The Labor Arbiter dismissed the case for lack of merit but the NLRC reversed the same on appeal. Hence, this petition by PFCCI. ISSUE: Whether or not dismissal is legal. HELD: The dismissal is illegal. The respondent has become a regular employee entitled to security of tenure. Regardless of the designation conferred upon by PFCCI to the respondent, the latter, having completed the probationary period and allowed to work thereafter, became a regular employee who may be dismissed only for just or authorized causes under our Labor Laws. Probationary employees, notwithstanding their limited tenure, are also entitled to security of tenure and they cannot be terminated except for just cause as provided by the Labor Code or under an employment contract. [Philippine Federation of Credit Cooperatives, Inc., et al vs. NLRC, G.R. No. 121071, December 11, 7998; Romero, J]