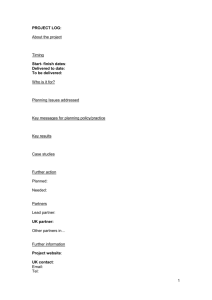

NESTA-Inventor Handbook - Justin Magee Directory listing

advertisement