Chapter1.WhyROP - Rite of Passage Journeys

advertisement

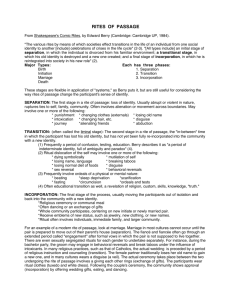

Rite of Passage Journeys Chapter I: Why a Rite of Passage? WHAT IS A RITE OF PASSAGE? We live in a time when it is confusing to be a youth. In former times, things were simpler. People were expected to grow up faster and take on adult responsibilities sooner. There was, in most societies, a clear pathway by which children and young people moved to adulthood. It began with the first childhood tasks they were given and concluded with the conferring of adult status by representatives of the larger community, usually in a ceremonial way. A RITE OF PASSAGE is a ritual or the ritualization of a transition or passage. A rite of passage is such a ceremony and marks the transition from one phase of life to another. Although it often refers to the tumultuous transition from adolescence to adulthood, it can refer to any of life’s transitions. There are many passages in our lives if we choose to mark and celebrate them. We use the word ‘passages’ to refer to the significant transition points in our lives. TYPES OF RITES OF PASSAGE There are many types of passages that we experience in our lifetimes. Dr. Angeles Arrien who is a cultural anthropologist, author and educator and has studied rites of passages extensively and cross-culturally sees them as falling into four main types: BIRTH, INITIATION, PARTNERING, and DEATH. BIRTH refers to those transitions that signify new beginnings. These can include starting a new business, moving to a new city or into a new home, bas well as the birth of a new baby and becoming a parent. Beginnings: Birth, First Day of School, New City or New Home, First day on a New Job, First Date, First Child, First Grandchild INITIATION is about learning and testing. One can be initiated into various new stages of life and takes on a new social role. The most common form of initiation happens as the community helps young people transition into adult status at puberty. This kind of initiation requires significant effort on the part of the initiate to master the knowledge of the culture and demonstrate they are ready to assume the role of adult Initiation: Puberty Rites, Coming of Age, Confirmation, Bar or Bat Mitzvah, Cotillion, Quinceaneros, Gang Initiation, Intern or Apprentice, Elderhood April 2009 – p.1 in that society. But initiation can be useful at other life transitions as well; for example, as a child moves into adolescence or an adult moves into elderhood. PARTNERING passages take place when things come together. Starting a new business partnership, a merger of organizations, and collaborating on a significant project are examples, along with the coming together of two lovers or the blending of two families. Partnering: Engagement, Marriage, Business Partneshipr, Community Organization ENDINGS is a time of finishing or letting go. Retirement and divorce are two ending passages we as a society must find more appropriate ways to mark. Endings: Death, Retirement, Being Fired, Divorce, Empty Nesting. WHAT IS AN INITIATORY RITE OF PASSAGE? At Journeys we are most concerned with initiatory rites of passage. Initiation is defined in the dictionary as “the rites, ceremonies, ordeals, or instructions with which a youth is formally invested with adult status in a community, society or sect.” Rites of Initiation have always been rooted in the community; that is, they are something that are done by the community for its members. Their intent was to shift the perception of youth toward their roles in the community and the perception of the community toward their youth. More importantly, however, initiation was about the creation, maintenance and continuity of the community. When a young Maasai initiate stood before the community, allowing himself to be circumcised without flinching, he was participating in an ancient ritual that assured that warriors would protect the village with all of their being, not turn to run or give up if they were injured or in pain. Initiation rituals also bonded the men of the village in a way that created the teamwork necessary for the hunt or the war party. In several cultures, when young women were taken away to the encampments of the women’s societies to learn the traditions of the tribe and the secrets which allowed women to maintain their power base in the community, the culture was being transmitted to the next generation and a similar bonding took place. Initiation is therefore fundamentally about the maintenance of community. In initiation, roles are defined and redefined. The stories that carry the values and history of the community are retold and learned so that they may be told again. Adults become elders as youth become adults, and the familiar (family) bonds are forged and tempered. As Michael Meade said, “Stories are the oldest school for humankind.” April 2009 – p.2 Initiation is about finding one’s home-–knowing who one is and where one comes from. Personal history is founded upon a unique genealogy passed on by parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles. In a true community, all people develop through active relationships. One’s personal cosmology is built upon that of those who have gone before. The experience of the elders and the ancestors has value because it is one’s dowry –- life tools which have worked for one’s forbearers and will continue to work into the future. A true community begins in the hearts of the people involved. It is not a place of distraction but a place of being. It is not a place where you reform, but a place you go home to. Finding a home is what people in community try and accomplish. In community it is possible to restore a supportive presence for one another. . . The others in community are the reason that one feels the way one feels. The elder cannot be an elder if there is no community to make him an elder. The young boy cannot feel secure if there is no elder whose silent presence gives him hope in life. The adult cannot be who he is unless there is a strong sense of presence of the other people around. This interdependency is what I call supportive presence. --Malidoma Somé in Ritual: Power, Healing and Community STAGES OF RITES OF PASSAGE There are three stages of a Rite of Passage that are commonly identified: 1. Severance or Separation is the time of stepping away from the old, from what one has been before, and may require a physical separation from one’s “old life.” During this stage one begins to shed old ties, old roles, and old ways of being so that one can be open to what is yet to come. 2. Threshold or Transition is the actual time of leaving all else behind and standing fully in an unfamiliar place where one must rely on one’s inner resources to find one’s way forward. This stage is also referred to as liminal space or liminality, the place of “no longer and not yet.” 3. Incorporation is the time to process the experience of the threshold and relate what one has learned to the world one will re-enter. This stage is about integrating those learnings into one’s life so that one can bring them back to the community. WHERE ARE THE MODERN RITES OF INITIATION? With few exceptions, children today do make the transition from youth to adult. So, what’s the problem? Why are we so concerned? April 2009 – p.3 Historically and cross-culturally, the purpose of initiation is to keep the youth connected to his or her community. In this century, in North America, we have almost lost this tradition, leaving youth often to initiate themselves. Gang initiations are an obvious example of how destructive self-initiation can be. In a gang initiation, the youth separate themselves from the community in a dramatic way, often including random acts of violence against the community, and consolidate their new role working against the interests of the community. Consider, also, parents who have fallen victim to an impossible-to-fulfill story called the Nuclear Family. Whether a couple or single, parents are expected to give all guidance, discipline, values and support to their offspring while working and commuting 50 to 60 hours per week. How are they to initiate their own children and into what society? In the past, parents would have turned to community elders but our modern society has become stratified; we have relegated the elders to insignificant, non-community related roles. Their life experience is ignored, and their participation in the rearing of children is sometimes even seen as objectionable. In former societies, the elders were those who cared for the society by initiating the youth and were seen as the wisdom keepers for the community. Now mostly we are unsure how to properly initiate our youth. Even our youth are confused: When we ask them how they will know when they are adults they give a shocking range of answers: driver’s license (the most common answer; the rest are in no particular order), graduation and moving to college, marriage, owning their first home, first sexual relationship, childbearing (sometimes a result of the former), and turning 21 (along with the right to consume alcohol and vote). What we find in these answers is that the story is slightly different for every youth because there is no clear culturally supported answer. We aren’t exactly sure what makes us adult, even those of us who are supposed to be adults. This hodge-podge of answers place our youth in ‘liminal space’ for a span of 15 years or longer, leaving them in a prolonged and difficult space for an undetermined amount of time. Besides being unsure of what rite of initiation really marks our transition into adulthood, our contemporary rites do not easily reach across social and economic lines. Not every youth can get their driver’s license and car at 16 and not every youth can move away to college or sometimes even graduate from high school. What do we do for the youth that cannot access these rites? Many of us who are doing Rites of Initiation work are doing so with the future of the larger community in mind. This task, however, is far too big for us. The larger community must once again assume the task. When youth (and adults) are left without a conscious marking and exploration of life transitions, they are unable to create positive change and growth in their own lives, not to mention taking that positive change into the world around them. Providing rite of passage experiences strengthens individuals, families, and the community as April 2009 – p.4 a whole. The individual learns what it means to be a responsible community member while exploring unique, personal gifts that can be used to serve others. OUTCOMES FOR THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE COMMUNITY What are the anticipated outcomes of an intentional initiatory rite of passage? When we design rites of passage experience, we work to assure that initiates come out of the experience with a new and empowering story that will help them take responsibility for the decisions that set the course for their future. We help initiates create the story of who they are and the kind of life they want to build that is based on an exploration of their own values. We also help them find the story that connects them to the community in which they will be actively related. Finally, integral to the story are the tangible symbols, artifacts of the journey, whose presence reminds and rehearses the decisions made while on the transformational journey. Initiates emerge with a stronger sense of personal responsibility to all aspects of themselves and their lives–-their families, communities, and the larger world of which they are a part, both the human world and the natural world. Having a sense of personal responsibility helps the young person relate their life story to that of the world and begin to extend their emerging sense of responsibility into the world. In this way both the community and the initiate benefit from the rite of passage. An intentional rite of passage experience provides the space for the community to transmit its core values and confer the role responsibilities appropriate to the initiate’s stage of life, thus insuring cultural continuity, a sort of knitting together of the generations. But that is only half the story. Through a rite of passage, the culture (community) and the individual enter into a reciprocal relationship. When the culturally transmitted values interact with the empowered story or the initiate those values are renewed and enlivened – and as the initiate lives his or her life story in meaningful relationship with the community, the community is revitalized. The initiate makes the values his or her own, internalizes them and lives them out through his or her life. But if values are transmitted but no renewal or revitalization occurs, the culture begins to die or at least becomes unhealthy because the individuals are no longer carrying the culture in their hearts. We can think of this dynamic between the individual and the culture in this way: April 2009 – p.5 The form and substance of a rite of passage experience communicates, cultivates and reinforces important cultural values. And, to the extent to which they engage in a meaningful way with the individual, they call forth the individual to use his or her power, gifts and passion in service to the community. When an individual takes on the responsibility to be all that he or she can be in service to the greater good, the culture is renewed and remains healthy and vibrant. It is important to remember this dynamic in designing rite of passage experiences and to make it an explicit part of the ‘curriculum’. We always remind adult questers that they are questing both for themselves and for their communities and ask them how they will carry their “vision” back to their communities--how they will use what they gained through their experience in service to their communities. With Journeys’ Coming of Age program that culminates with a Parent’s Weekend (for youth ages 12-14), we ask youth and parents to consciously and intentionally renegotiate their roles, specifically by talking about how privileges and responsibilities will be shifting over the next several years. It is important to note that when we are conducting rite of passage experiences for real people in the real world, outcomes may not be readily or immediately apparent. Often participants may just gain a glimpse of their authentic selves, an intimation of their future lives. Answers to the questions they ask of themselves may be elusive. It is important that we as guides or designers of these kinds of experiences hold the question of outcomes lightly; that is that we don’t try to impose pre-determined outcomes on participants, but rather understand that we are trying to help individuals find their own paths of growth and development within a supportive community. We are asking them to begin or further a conversation with themselves about who they are and what role their can play in the on-going work of renewing and ensuring the health of their society and culture. THE HERO’S OR HEROINE’S JOURNEY Central to the work of creating and conducting “…Furthermore, we have not ever to risk the journey alone, April 2009 – p.6 initiatory rites of passage for youth and adults is the recognition of the archetype of the hero (and heroine) and the hero’s journey. The Hero’s Journey as an archetype was explored and described by Joseph Campbell in his book, Hero with a Thousand Faces, first published in 1949. Through the Hero’s Journey, we are called to see ourselves as the hero or the heroine of our stories, abandoning modern media distortions about who and what we should be in favor of finding and becoming who we really are. Such a re-imagination of what it means to be a human being is not to nurture our egos or to inflate our importance. Rather, it provides us with a framework through which to view our lives that help us see more clearly the importance of taking personal responsibility for the decisions we make and actions we take along the way and the personal courage required to do that. for the heroes of all time have gone before us. The labyrinth is thoroughly known. We have only to follow the thread of the hero path, and where we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god. And where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves. Where we had thought to travel outward, we will come to the center of our own existence. And where we had thought to be alone, we will be with all the world.” Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth The “Hero’s Journey” is best understood as a cyclical process. Linear presentations fail to recognize the spiral nature of the motion by which it can move through our lives. Central to the story is a picture of a journey “between two worlds.” There are those who are prepared to risk the leap from this world into the other world where new experiences, new challenges and the unknown live. Potentially it is a fearful place, guarded by ogres of human anxiety and filled with the promise of uncertain reward. No one leaves this other world quite the same person as they entered. It is in this other world that the rite of passage happens. The following is a simplified image of The Hero’s Journey that Joseph Campbell mapped through his explorations of thousands of myths and stories from around the world through human history. It offers us a way of understanding the process by which one becomes who he or she has it in them to be. April 2009 – p.7 In this map there are six distinct stages, two of which are thresholds between worlds. In the real world, participants of intentional rite of passage experiences may zigzag between stages, and the journey may never reach a definitive point of resolution. However, for simplicity’s sake, the spiral image depicts a pathway of heroic progression and triumph. These stages are as follows: 1. The Call to Adventure is a call to release the daredevil in each of us, to reach out for the next stage of our lives. The call is the mysterious and intoxicating voice that calls us from the sleep of our routine lives--a charismatic call from within to risk and discover what comes next. 2. The Threshold of Ogres is the bumpy crossing into the ‘Other’ world. In the same way that Hades greeted the ancient Greeks on their journey into the Underworld, the hero or heroine will encounter the ogres of their individual mythology. There April 2009 – p.8 are ogres of exhaustion, thirst, estrangement, indecision, responsibility, growing up, and so on. The Threshold of Ogres involves a complex process of letting go and opening up to receive the new. It is where our resolve is tested and courage is needed. 3. The Road of Trials and Finding Allies stage is tricky to manoever because it offers many deceptions. The experience of the trials may distort the vision so that allies are cloaked in a misty haze. The hero or heroine must sustain the momentum of the quest; yet still find the time to stop, look and listen. The earth and the animals may have important messages or clues. Sources of help are unpredictable and frequently appear in such a way as to challenge assumptions or prejudices, indifference or fears. 4. The Magic Flight is a fluid stage that weaves magic into the journey of the hero or heroine, a melodic dance in which the hero or heroine is the charismatic leader and pivot of inspiration. Magic flight celebrates a spontaneous and acute connectedness with personal power. It is a place in the imagination where individuals become confident in their abilities and released from pre-conceived notions of self. Magic Flight holds the promise of all things possible. 5. The Return Threshold marks the transition out of the ‘Other’ and back into this world. Although ogres leave the crossing unchallenged, it still holds a certain trauma. What seemed easy in the surrealistic realm of magic flight may be difficult to implement in everyday life. During this stage the individual decides either to integrate their otherworldly experience into a daily reality or to abandon it as an abstract dream. This stage is crucial to the journey. 6. The Master of Two Worlds is coming back into the world with the recognition that they “did it!!” They set out to achieve, encountered trials and challenges and pushed through them. Here is an experimental ground for testing their ability to make things happen on their own. The keys to remaining the “Master of Two Worlds” are self-discipline, determination and integrity. There is barely a chance to climb the mountain and breathe the fresh air before the process starts all over again. The call is relentless and insistent. April 2009 – p.9