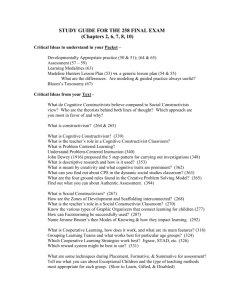

Learning Theories

advertisement

Associationism Associationism is the theory that all experience can be reduced to elements of ideas and sensations. An experience may start with a sensation that leads to an idea, which leads to another idea that leads to another sensation. Experiences then become a succession of sensations and ideas. One of the earliest associations people make is between the word “mama” and the caregiver who is connected with that word. The word mama is an idea and that particular person holding and feeding the baby is a sensation for the baby. Other words are then linked with the objects or people for which the connection is appropriate. The associations can become complex, such as a child seeing five different breads of dogs, all of various sizes and colors, and knowing that each is a dog. If a person ate a certain food for supper and woke up the next day with the flu, then in that persons mind, the two may have an eternal link. The food is an idea and the feeling of nausea at the thought of the food is a sensation. The sight of lighting is associated with the sound of thunder. Children learn to be afraid of lighting, not because of the actual danger it posses, but because it is followed by a loud scary noise. Associationism has its roots in Aristotle’s “empiricism.” Aristotle contended that all knowledge came from experience. Ideas either trigger or lead to other ideas. These ideas help an individual to recall other ideas that may be closely related to the original idea or not. John Locke (1632-1704) also was a propionate of this idea. He believed that no innate ideas existed. At birth, the mind is a “tabula rasa,” and the “Knowledge is the perception of the agreement or disagreement of two ides.” George Berkeley (1685-1753) contended that the mind is the only reality and that ideas come from experiences. David Hume (1711-1776) believed that people experienced reality through their ideas. James Mill is the major proponents of the theory that came to be known as “Associationism.” James Mill was an amateur psychologist and philosopher. He continued the work begun by Aristotle and continued by Locke. Over a series of summer vacations, he wrote his book entitled “Analysis of the Phenomena of the Human Mind,” which was published in 1829. In his book he outlines the “idea” and “sensation” components which are the basis for the associationism theory. In addition, he further defined his theory by dividing it into what he called “synchronous associations” and “successive associations.” Synchronous associations are associations that occur together, such as entering a highly decorated room. All of the senses are at work at the same time. Successive associations are ones that occur in succession, such as a thunder storm. The lighting is seen, the thunder is heard, and perhaps even the room shakes. He therefore summed up that all experiences are able to be reduced to associations that are formed among simple elements. References Jones, J. & Wilson, W. (1987). An Incomplete education. (pp.311-312) New York, NY: Ballantine Books. Malone, John C. (1991). Theories of learning; A historical approach. (pp. 7-9, 27) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Schunk, D.H. (2000). Learning theories; an educational perspective. (pp. 17-18). Upper Saddle River, NJ. Prentice Hall, Inc. Behaviorism Behaviorism is the educational psychology theory that deems a behavior is influenced by a combination of the behavior and the environment or environmental stimuli in which the learning takes place. The basis of the behaviorist approach is to consider the observable response and the observable behavior. This theory is based on activity and the stimulus for the activity. For example, when a small child drinks his milk every morning and is given a piece of candy, he will probably wish to drink his milk every morning. If the boy is in the habit of drinking his milk and then every morning when he did so, he was scolded to the point that he becomes upset, the child could come to dislike milk. He could also stop wanted to drink anything liquid. Therefore any experiment that deals with determining or changing human behavior has to be tempered with good judgment. The study of stimulus and response behavior has its roots in the work of Edward L. Thorndike (1874-1949), and Ivan P. Pavlov (1849-1936), with further work by Burrhus F. Skinner (1904-1990) and Edwin R. Guthrie (1886-1959). However it was the American psychologist John B. Watson (1878- 1958) that is credited with coining the term “behaviorism” and is the attributed with being the leading authority on the subject. The date of 1913 has been attached to this term coming into the psychology vocabulary. Although Watson was respected for his work early in his carrier, it was his work after 1915 that set him apart as an individual. Prior to 1915, his work was based on the observation of animal behavior. He then became interested in child development. One of his best known experiments was titled “Little Albert.” During the course of this treatment, an 11 month boy was conditioned to go from a complete lack of fear of a white rat to being terrified of anything white and furry, including a fur coat. This was accomplished by striking a hammer against a steel bar when the boy reached for the rat. The noise frightened the boy each time it occurred. After a period of a couple of weeks, the rat could be presented to the boy and he would become emotional. Watson felt he could take any baby and produce any kind of human being from a doctor to a thief. His belief was that “great men are made not born” (Watson, 1927). Watson also was more extreme in his experiments in behavior modification than any of his predecessors. He had very precise ideas about child rearing and raised his own children in the perfect behaviorism fashion. His beliefs included almost a total lack of emotional support and physical contact with his children. In this respect, he totally missed his mark for his children grew up with physical ailments that stemmed from emotional problems. One of his children committed suicide. Watson was born in Greenville, South Carolina and grew up on a farm. He graduated from Furman University and continued his education at the University of Chicago. At the age of 25 he was awarded his Ph.D. earning the distinction of being the youngest student in the history of the school to do so. He joined the faculty of the University of Chicago for five years, leaving for the position of department chairmanship at Johns Hopkins. Watson’s academic career came to a halt in 1920 after an affair with a graduate student, that lead to both a divorce and the forced resignation of his position at Johns Hopkins. He moved to New York City and procured a job at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency. He was very successful in advertising interestingly due to his past work in behavioral psychology. Up until this point in time, products were sold on their merit of what the product could do. Baby powder, for example, was medicated for the health of babies. Watson promoted products for the image they could produce. A certain brand of baby powder acquainted the mother with being loving and caring. This was one of the first times in advertising history that image was promoted. In modern day advertising, the majority of advertising uses the idea of “selling the sizzle, not the steak.” References Abeles, H.; Hoffer, C. and Klotman. (1984). Foundations of music education. (pp. 161–163). New York, NY: Schirmer Books. Ashman, A.F. and Conway, R. (1997). An introduction to cognitive education; Theory and applications. (pp.18-19). New York, NY: Routledge. Buckley, K. (1989). Mechanical man; John Broadus Watson and the beginnings of behaviorism. New York: The Guilford Press. Malone, John C. (1991). Theories of learning; A historical approach. (pp. 24-27) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Schunk, D.H. (2000). Learning theories; an educational perspective. (pp. 42-44). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. Information processing The term “information processing” refers to the multiple progressions that happen as a cognitive process of learning and in turn of solving problems. This processing usually follows some form of a sequential pattern. Where as information processing resembles associationism, it focuses on the internal or mental process rather than the external process of associationism. This theory begins with the work of J. P. Das in the mid 1970’s in a response to determine why some children did not learn as well as others. He theorized that one reason was their inability to “code” information in such a way that they could understand and remember it. Das devised strategies to help the children. There is however inconclusive evidence so suggest that his strategies work with all learning disabilities or age groups. One problem with older students is their failing to see any relevance of the strategies and therefore do not take them seriously. Work done by Ebbinghaus on verbal learning resulted in several conclusions. In learning a list of terms, it was found that words (items that had meaning) were learned with more ease that nonsense syllables. Items that had some form of similarity were easier learned than items that had no relationship. Information processing includes four major categories. They are attention or stimulus, perception, short term (working) memory and long term memory. When a stimulus is introduced, one or more of senses is engaged. Then perception or pattern recognition puts the stimulus in the correct cognitive category. The information is then transferred into short term memory. Short term memory is temporary mental storage and can only maintain a small amount of information. Only five to nine numbers can be handled by short term memory. For information to enter long term memory it must be rehearsed. If it is not rehearsed, it quickly leaves the short term memory. Long term memory is affected by frequency and contiguity. The more frequent an idea is returned to, the stronger it becomes in long term memory. Also, if two experiences occur at the same time, they will be linked and both will be recalled when a stimulas for either one arises. Traditionally tests of intelligence measure an academic ability, not a student’s information processing competence. The “Raven’s Progressive Matrices of Intelligence” test is a measuring device that shows logical relationships and simultaneous processing. The “Porteus Maze Test” also evaluates information planning. Because of the small number of diagnostic devices to measure information processing abilities or styles, most information that is available is based on primarily experimental techniques. Information processing is an area in which more research is needed. References Ashman, A.F. and Conway, R. (1997). An introduction to cognitive education; Theory and applications. (pp.121-122; 128, 168-9, 179). New York, NY: Routledge. Andlin, G. Ed. (1995). Instructional technology; past, present, and future. Second Edition. (p. 121-122, 128, 168-9, 179) Englewood, CO. Libraries Unlimited, Inc. Schunk, D.H. (2000). Learning theories; an educational perspective. (pp. 120-126, 138-141). Upper Saddle River, NJ. Prentice Hall, Inc. Cognitive/ Learning Styles The various ways in which students perceive, process, organize, and store information is known as cognitive or learning styles. This theory takes into consideration each student’s individual way in which he learns. Exploring learning styles is a concept that has arisen only in the last 30 to 40 years. This concept takes into consideration that students learn differently. This is not to be confused however with the various abilities that individuals possess. The broad category of cognitive styles is broken into three areas. The first area is field dependence- independence. The second area is categorization style, and the third is cognitive tempo. Field dependence-independence refers to the manner in which a person uses the area around them for information processing. Some students may learn better in a global manner. This would be field dependent. Other can process information better in an analytical manner. This would correlate to being field independent. These learning differences do not mean there is a difference in the ability to learn, only the situation in which some students learn best. It has been found that younger children are generally field dependent, where as older children start becoming field independent. There is also a physical component to being field dependent or independent. Various physical exercises have been performed such as having people sit in a tilted chair which is in a tilted room. They are then asked to tilt the chair upright. People who can accomplish this are said to be field independent. Categorization style is the way in which a person groups objects or information according to the similarities that are perceived. For example, a person could be shown pictures of all different kinds of transportation and then be asked to group the pictures. A logical grouping would be groups of boats, planes, and motor vehicles. The pictures could however be grouped according to the number of people that can be transported on each such as a cruse ship verses a row boat. The group could also be put into the two categories of motorized, such as a motorcycle, or non-motorized, such as a bicycle. Cognitive tempo, also known as conceptual response, refers to the quickness of student when responding to a posed question. Some students respond very quickly while others were more reflective before responding. Students who responded quickly were categorized as impulsive where as the students that took time to analyze the problem were classified as being reflective. Kagan, one of the main researches of this division of learning styles devised a test to determine cognitive tempo. It was found that impulsive students had a response time that was above the mean whereas their accuracy scores were below the median. The exact opposite was true for the reflective group. There were also two other groups of students. One group was fast and accurate and the other was slow and inaccurate. These two groups were exceptions to the overall mean. For a student to be aware of his learning style can be important in not only helping him learn and achieve, but also in determining what activities or even vocations that could be most suitable. Someone who is able to make quick and accurate choices could be successful in a job that called for quick decisions. A person who is able to reflect, analyze and make a quality judgment would be valuable in a vocation that needed that kind of a learner. References Andlin, G. Ed. (1995). Instructional technology; past, present, and future. Second Edition. (pp. 53 & 57). Englewood, CO. Libraries Unlimited, Inc. Malone, John C. (1991). Theories of learning; A historical approach. (pp. 7-9, 27) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Schunk, D.H. (2000). Learning theories; an educational perspective. (pp. 421-425). Upper Saddle River, NJ. Prentice Hall, Inc. Constructivism Constructivism is the theory that students learn by constructing different experiences into a knowledge of particular subject areas. The basis for constructivism is that the student is an active learner. This is in direct opposition of the lecture method of teaching where the student is playing a passive role. This theory is in direct opposition of Instructivism. Facts are not learned to be remembered for the test. Information is to be learned so that is can be used in a larger sense. In constructivism, students learn new information by engaging in a variety of activities from reading, to group work, drawing pictures, building models, taking field trips and such. By this activity, students learn from observation, trial and error, working collaboratively, and any other action that causes the student to be in charge of his own learning. This is very much a student centered belief. The area of constructivism is broken into three main areas. The first is exogenous. This belief is based on the idea that all learning is reconstructed from the outside world. Modeling and various experiences are basic to this area of belief. Endogenous is the second subdivision and holds that knowledge comes from previous knowledge. The third area is Dialectical. This area is based on the belief that knowledge comes from interactions between people and the environment in which they interact. The idea of constructivism is a new idea that has been introduced into the theories of the field of learning within the past two decades. Different parts of the theory resemble the framework of other theories. The endogenous part of the theory closely resembles the Piaget idea of cognitive development. The dialectical subdivision of the theory, which emphasizes the interaction of environmental influences, resembles the ideas of Bandura, Vygotsky and Bruner. One criticism of this theory is that it offers no hypothesis that can be tested. Because the student is constructing their own understanding, no two students will learn the same thing from the same material. Therefore, although some students may enjoy this type of learning, measuring what was learning is difficult. Also, other than a broad based outline, no predetermined content can be applied. It also offers no structure to students who are not independent learners or thinkers. Additionally, close supervision is needed to insure that the students are staying on task. More over, teachers who feel most comfortable by being in total control of learning will probably not be advocates of this particular type of acquisition of knowledge. One advantage of constructivist learning is that it allows creative students to enhance the subject matter they are assigned as the normal course of the lesson. Because it allows students to have input in what they learn, the topics of study may become more engaging. Because students are engaged in an activity, this could also help in reducing class behavior problems. Allowing students to be independent in their learning is a trait that can help students later as they enter the job market and different points of view are considered valuable in making the company successful. References Andlin, G. Ed. (1995). Instructional technology; past, present, and future. Second Edition. (pp. 41, 53, 104 – 106). Englewood, CO. Libraries Unlimited, Inc. Malone, John C. (1991). Theories of learning; A historical approach. (pp. 7-9, 27) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Schunk, D.H. (2000). Learning theories; an educational perspective. (pp. 229-230). Upper Saddle River, NJ. Prentice Hall, Inc. Programmed Instruction Programmed Instruction is a systematic method of presenting small amounts of material to students in a building process of them getting the big picture. For example, when a student is learning to play the piano, only a few notes are introduced at a time, and the hands work on playing one at time. The idea of programmed instruction began in the 1920’s with the work of Sidney Pressey. Pressey designed machines which presented a student a series of questions in a multiple choice format. If the student chooses the correct answer he would be allowed to go to the next question. If the student chooses the incorrect answer, he would not advance until the correct answer was chosen. A score of correct and incorrect answers was kept. B.F. Skinner, a proponent of behavior modification, advanced the machine of Pressey by including an instruction component. Instead of a series of multiple choice questions being posed, sequenced material was presented with an overt question following. Like Pressey’s machine, if the student answered the question correctly, he preceded to the next frame. Unlike Pressey’s machine, if the student was incorrect in his response, he was presented with additional material. The objective was to help the student minimize errors and to be successful in advancing through the material by giving immediate feedback and presenting material in a manner to lead the student to the correct answer. The “teaching machine” has in recent years been replaced by computer software. There are several steps that Programmed Instruction incorporates. The first is to define what the student is going to be able to do after the lesson has been completed. The second step is to present the material in subdivided frames. The idea of the frames is fundamental to the Programmed Instruction concept. The frame concept is a method of keeping each segment of material small. The third step in Programmed Instruction is that a student can learn at his own pace. This helps to element the boredom that can occur in a student who grasps the material quickly and gives supplementary material for the student who need a bit more help. The fourth is the student is an active in his learning due to the act of responding to questions as they progress through the program. Lastly, the feedback students receive is dependent on their response. A correct response allows advancement to the new question. An incorrect answer allows the student additional information and a restatement of the question. One criticism of Programmed Instruction is the level of easy success it tries to incorporate. Making the students successful is one of the foundational points to Programmed Instruction. However it was found that students became more persistent in the questions they missed. A combination of a majority of correct questions with a few missed ones was viewed to be a better indicator of what an individual student was capable. Research indicates that Programmed Instruction is effective learning tool, especially for students that need remedial work or for independent study situation. Malone, John C. (1991). Theories of learning; A historical approach. (p. 223) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Schunk, D.H. (2000). Learning theories; an educational perspective. (pp. 69-72). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. Social Cognition The Social Cognitive theory is a belief that much of a person's learning occurs in a social situation. The social environment is where attitudes are formed, beliefs are founded and social rules are learned. Therefore modeling is an important way in which people learn. It is by watching others that many strategies for using appropriate behavior and avoiding the consequences for inappropriate behaviors are acquired. The theory of social cognation began with the theory of social learning. The major proponents of this theory were Neal Miller and his co-worker J. Dollard. Miller received his doctorate from Yale and then spent the next several months studying at the Psychoanalytic Institute in Vienna in an effort to learn as much about the Freudian as possible. Miller later joined the faculty at Yale. Slong with his college John Dollard, Miller reduced the theories of Miller’s teacher, Hull, into the four basic elements of drive, cue, response, and reward. They also showed evidence that imitation in learning a behavior is dependent on reward. For example, when Grandfather comes to visit, the older children know that he always brings presents for them. At the news of Grandfathers visit, the older children grow excited and watch out the window for his arrival. The youngest child does not know who grandfather is but imitates the behavior of the older children by watching out the window. When Grandfather arrives, the older children surround him, so the youngest does as well. Grandfather comes in and everyone gets a new toy. The next Grandfather comes to visit, and the drive has been established in the youngest child by the reward of the toy. The behavior of the older children becomes a cue and the response is watching out the window. Miller and Dollard further found that children quickly learned to imitate the behavior that received a reward and did not model the behavior that got no reward. Children were able to model the appropriate behavior even when it was exhibited by someone their own age as opposed to the poor behavior demonstrated by a college student. Albert Bandura continued this work with some modifications in Miller's and Dollard's original work. He also renamed it Social Cognation. Bandura was born in Alberta Canada, but came to the United States for his doctorial work as well as his teaching career. Bandura differed from his predecessors in that he felt people could learn merely by observing without having to demonstrate the behavior in order to learn from it. He also contended that if a behavior was to be imitated, it did not have to be done so at the time of the observation. Also, reinforcement or rewards were not necessary. The social cognitive theory holds an importance for education in that situations to learn from social behaviors occur everyday. A student’s school environment will probably be the most social situation of his entire life. Therefore it is the foundation for life shaping. References Malone, John C. (1991). Theories of learning; A historical approach. (pp. 178-182) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Schunk, D.H. (2000). Learning theories; an educational perspective. (pp. 78-118). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc.