Introduction - Facstaff Bucknell

advertisement

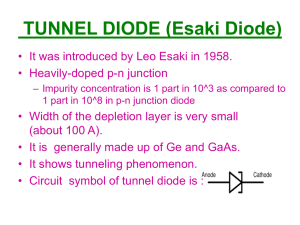

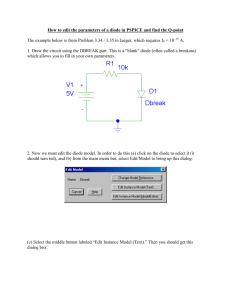

ELEC 350L Electronics I Laboratory Fall 2005 Lab #7: Semiconductor Diode Characteristics Introduction Semiconductor diodes are employed in a wide range of electronic circuit applications. However, unlike resistors, capacitors, inductors, and most sources, diodes are nonlinear devices; that is, the voltage across their terminals is not directly proportional to the current that flows through them. (For capacitors and inductors in the frequency domain, the linear relationship is in the form of a simple multiplication by 1/jωC or jωL, respectively. In the time domain, the linear relationship is in the form of derivatives or integrals.) One consequence of this is that diode circuits do not in general obey the principle of superposition, and linear analysis techniques such as nodal and mesh analysis cannot be applied to them. Unless some simplifying approximations are made, other analysis approaches must be used, and these depend upon knowing the i-v characteristic of the diode or diodes in question. In this lab experiment you will determine the i-v characteristic of a semiconductor diode made of silicon. There will be times in your career when you will need information about devices and circuits that is not given in manufacturers’ data sheets. In these situations it will be up to you to plan a series of measurements in order to obtain the data you need. The experimental procedure for this lab is not outlined as explicitly as those of past labs. Part of the purpose of this experiment is to help you practice devising test procedures on your own. Theoretical Background The semiconductors found in most modern electronic devices are made of tiny crystals of silicon, germanium, or other similar elements that have been tainted slightly with small concentrations of other elements. The purpose of these impurity elements, usually called dopants, is to create a supply of free electrons or holes (absences of electrons) that are not bound in the crystal structure. In a crystal of pure silicon all of the valence electrons are trapped close to the silicon nuclei in covalent bonds, but a doped crystal has either an excess or a deficiency of valence electrons. Whether p-type or n-type, however, a doped sample of silicon is still electrically neutral; that is, the numbers of electrons and protons in the sample are the same. The impurities impart a significantly higher conductivity to the crystal. If the dopant creates a supply of free electrons, the modified crystal is called n-type material (since electrons are negatively charged). If the modified crystal has a supply of holes, the material is called p-type (since holes are positive). Because free electrons and holes are not held in place by tight covalent bonds, they move easily under the influence of an applied voltage. Hence, the conductivity increases. The structure of a basic semiconductor diode is shown in Figure 1. A section of n-type material abuts a section of p-type material to form a pn junction. The diode symbol is shown just below the pn junction in the orientation corresponding to the arrangement of the p- and n-type materials. If a resistor and a voltage source are connected to the diode as shown in Figure 1, a significant amount of current will flow through the circuit. In this case, the diode is said to be 1 forward-biased. If the polarity of the voltage source is reversed, a very small amount of current will flow (on the order of nanoamps). The diode is then said to be reverse-biased. The voltage vD across the diode and the current iD that flows through it are related to each other, but not linearly. p n diode + _ vD iD _ + R vs Figure 1. Physical construction, symbol, and forward-biasing of a semiconductor diode. The behavior of the holes and electrons on both sides of the pn junction under the influence of an external source leads to a nonlinear i-v characteristic for the diode given by i D I S e vD / nVT 1 , which is known as the diode equation. The constant IS is called the saturation current (or sometimes the scale current or reverse current) and is the amount of current that flows through the diode when it is reverse-biased, the state that corresponds to negative vD. Its value usually varies between 10–8 and 10–14 A for discrete devices (stand-alone diodes not found in integrated circuits) at room temperature. Typically, the value of IS is on the order of nanoamps. The constant n is called the emission coefficient and is empirically (experimentally) determined. Its value is usually close to unity (one) for germanium diodes and close to two for silicon diodes in normal operation. The constant VT is called the thermal voltage or the volt-equivalent of temperature and is given by T , VT 11,600 where T is measured in degrees Kelvin. At warm temperatures (300 K, 27 C, or 81 F) VT is approximately 26 mV. Note that the diode equation applies whether the diode is forward-biased 2 (vD > 0) or reverse-biased (vD < 0). If the diode is reverse-biased, then e vD / nVT 1 ; the diode current iD has a negative value (approximately –IS); and the actual direction of the tiny current is opposite to that indicated by the arrow in Figure 1. A diode’s i-v characteristic, which is mathematically expressed by the diode equation, has the general shape shown in Figure 2. The distance between the horizontal axis and the curve for negative vD is exaggerated to show that the current is negative for the reverse-bias case. If the left-hand (negative-vD) part of the curve were drawn to scale, it would be so close to the horizontal axis that it would be impossible to discern from the plot that iD is negative when vD is negative. iD IS vD Figure 2. Typical i-v characteristic for a semiconductor diode. Experimental Procedure Your main task is to determine the i-v characteristic of two types of silicon diodes using a test procedure of your own design. You should gather enough data in order to produce a curve like the one shown in Figure 2 for positive values of vD only. (The reverse saturation current IS is too small to measure easily. It will be determined indirectly later.) The “knee” in the curve (where it turns sharply upward) occurs at a vD value of several tenths (or perhaps many tenths) of a volt, so your maximum value of vD should be well beyond that point. Remember that vD is the voltage measured across the terminals of the diode, not the value of any applied voltage source. Your measurement approach should prevent excessive current from flowing through the diode; consult the relevant data sheets to find out what the current limits should be. Make sure you include in your notebook a complete but concise description of the test procedure you devise. There should be a sufficient amount of detail so that another engineer could read your description and repeat your measurements successfully. Using the test procedure you devise, determine the i-v characteristic of a 1N914 or 1N4148 diode, whichever type is available. You are highly encouraged to organize your measured data in tabular form. 3 Sketch or print out a copy of the i-v characteristic for your diode. After you have finished taking measurements, you may ask the instructor to verify your i-v curve using a piece of test equipment known as a curve tracer. Apply your measurement procedure again to find the i-v characteristic for a 1N4007 rectifier diode. This is a heavy-duty diode used in power supplies, so it is possible that you will have to allow more current to flow through it than the 1N914/1N4148 to get past the “knee” in the i-v characteristic. Note that the value of vD at which the “knee” occurs could be significantly higher than it is for the first diode. Sketch or print out a copy of the i-v characteristic. From the i-v data you have collected, determine the values of the parameters IS and n for each diode, assuming that the value of VT obtained using the equation given above in the “Theoretical Background” section is exact. (You’ll need to estimate the temperature of the room in degrees K.) For reasons explained below, you are not likely to get good results if you blindly use the “trend line” (curve-fitting) feature of your calculator or spreadsheet to do this. You can find the parameters via trial-and-error, but there is an easier way. Note that when vD is “large” the diode equation simplifies to i D I S e vD / nVT . Taking the natural logarithm of both sides leads to ln i D ln I S e vD / nVT ln I S ln e vD / nVT ln I S vD . nVT Because IS, n, and VT are constants, this implies that a semi-log plot of iD vs. vD should be a straight line over the range of vD values for which the approximation given above is valid. (Note that the natural logarithm is used here, not the common logarithm.) This should suggest to you a simple way to find IS and n. Clearly explain in your notebook the procedure you end up using. Note: The diode equation is not applicable over the entire range of safe operation of a diode, although it is usually valid over the typical range of operation. Of course, vD must be large enough so that the approximation given above is valid. But as vD increases well above the “knee” in the curve the i-v characteristic also departs from the simple exponential relationship. In the latter case a diode begins to take on the characteristics of a resistor (which has a linear, rather than exponential, i-v characteristic). One of your tasks is to determine the range of your measurements over which the diode equation is applicable (and over which your method to find IS and n should be applied). Comment on the degree to which your calculated values of IS agree with the typical values for that parameter given by the appropriate data sheets. Also discuss whether or not your calculated values of n fall within the range of typical values (1-2) for silicon diodes. Links to data sheets for the 1N914 and 1N4007 diodes are available on the “Laboratory” page. 4