General Court (EU), Judgment of 30 September 2010, Case T

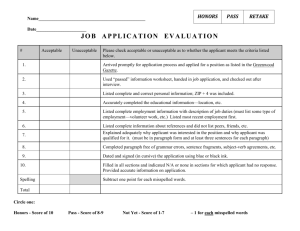

advertisement