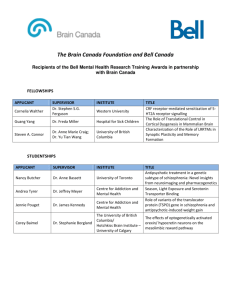

Schizophrenia

advertisement

The Disease Called Schizophrenia 1 Denise L Dellone Psychology 213: Abnormal Psychology April 1st 2013 The Disease Called Schizophrenia 2 The Disease Called Schizophrenia Schizophrenia is a disorder in which personal, social and occupational functioning deteriorate as a result of disturbed thought processes, distorted perceptions, unusual emotions and motor abnormalities. Approximately one percent of the worlds population suffers from this disorder. The DSM-IV identifies five patterns of schizophrenia: disorganized which is characterized by disorganized speech, disorganized behavior, and flat or inappropriate affect, catatonic schizophrenia described as physical symptoms including either immobility or excessive motor activity and the assumption of bizarre postures. In in-differentiated schizophrenia , symptoms are mixed. Residual schizophrenia episodes are defined by the reemergence of prominent psychotic symptoms, paranoid schizophrenia is characterized by preoccupied with delusions or auditory hallucinations without prominent disorganized speech or inappropriate affect, patients with paranoid schizophrenia tend to be less severely disabled and more responsive to available treatments. The term Schizophrenia comes from the Greek word for “split mind” and is less than 100 years old. The disease was first identified as a discrete mental illness by Dr. Emil Kraepelin in 1887. Kraepelin believed the chief origin of psychiatric disease to be both a biological and genetic malfunction. Schizophrenia is more common among relatives of people with the disorder. A study performed on the interaction between parental psychosis and the risk factors during pregnancy was to investigate the association between parental psychosis and potential risk factors for schizophrenia and their interaction. The study evaluated whether the factors during pregnancy and birth have a different effect among subjects with or without a history of parental psychosis and whether parental psychosis may even explain the effects in the risk of schizophrenia. High birth weight and length and high maternal education had a significant interaction with parental psychosis. The presence of any biological risk factor increased the risk of schizophrenia significantly only among the parental The Disease Called Schizophrenia 3 psychosis group; whereas the presence of any psychosocial risk factor had no interaction with parental psychosis. Parental psychosis can act as a modifier on early risk factors for schizophrenia. The results found that the evaluation of the mechanisms behind the risk factors should, therefore, include consideration of the parental history of psychosis(Keskinen et al. 57). Kraeplin also believed that schizophrenia has a deteriorating course in which mental function continuously declines. People with Schizophrenia have unusual perceptions, odd thoughts, disturbed emotions and motor abnormalities. These individuals experience psychosis, a loss of contact with reality. Their ability to perceive and respond to the environment becomes so disturbed that they might not be able to function at home, with families, in school or at work. They may have hallucinations, or delusions or they may withdraw into a private world. The prototypical, natural history of Schizophrenia begins with three phases that usually appear between late teens and mid thirties these phases are premorbid, those who have experienced subthreshold, positive psychotic symptoms during the last year, prodromal, those who have experienced brief episodes of frank psychotic symptoms that has spontaneously resolved and psychotic, these patients have a first degree relative with a psychotic disorder combined with a significant decrease in functioning during the previous year. The symptoms include depression and anxiety, sleep problems, and poor self-care, as well as environmental difficulties. Some patients are able to describe how their thinking and perception of the world has changed in subtle yet discernible ways. Psychosocial decline noted by family or peers and depressive symptoms reported by patients are typical precipitants for seeking help. Other symptoms that can be often elicited are cognitive and emotional disturbances, low energy and impaired stress tolerance. Once an individual is at a psychosis threshold they can be admittedly arbitrary and not always clear clinically, particularly in patients with brief, stuttering episodes of low-level psychotic symptoms. Substance use and a wide variety of medical illnesses can mimic Schizophrenia. The clinical yield for routine brain-imaging studies and MRI's are usually The Disease Called Schizophrenia 4 considered low, with one to two percent typically requiring medical interventions. (Freudenreich et al. 191). Schizophrenia in subjects younger than thirteen years old is defined as very early onset schizophrenia. Its prevalence is estimated at 1 in 100,000. While early onset schizophrenia occurs between thirteen and seventeen years of age, its prevalence is about 0.5%. Only a minority of youths show a complete recovery, and the majority of patients present a moderate to severe impairment at the onset (Masi et al 201). Schizophrenia is found more frequently in lower level societies, and African Americans are more likely than White to have symptoms of hallucinations, paranoia, and suspiciousness. Although schizophrenia is consistently associated with an increase rush of violence compared with general population, most individuals with schizophrenia are not dangerous. It is recognized that the risk for schizophrenia occurs on a continuum with certain factors of the illness, pre and perinatal brain insults, delayed developmental milestones, and abuse during childhood placing the individual at increased risk. Although they all are associated with increased rates of schizophrenia compared to the general population, the majority of people who have these factors do not develop the disorder. The majority of people who develop schizophrenia is generally not longer than a few years, with an average duration of about one year. This has been seen as a legitimate target for detection and intervention, with the aim of prevention at onset or at least delay the onset (Smith 916). There are negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia, the positive symptoms are bizarre additions, such as delusions, disorganized thinking and speech, heightened perceptions and hallucinations. Negative symptoms are characteristics that are lacking in an individual. Poverty of speech, blunted and flat affect, loss of violation and social withdrawal. Psycho-motor or catatonic symptoms can be awkward movements in repeated grimaces and odd gestures. The unusual gestures seem to have a private purpose. Perhaps ritualistic or magical. (Comer 427-432). All individuals inhibit multiple social identities that are influenced by the social context. The The Disease Called Schizophrenia 5 social context provides relationships that promote and inhibit the enactment of social identities, and it transmits ideologies that assign value and status to particular identities, and to the patients insight. The individual developing a post-diagnosis identity faces this process of evaluation in all their social interactions. Unfortunately, a person who is diagnosed with schizophrenia undergoes that process in a highly problematic way. In psychiatry, the term insight is used to refer to the capacity to recognize that one has an illness that requires treatment. People who rarely present to clinical services are concerned about the risk of developing schizophrenia. More often they seek help for a range of psychiatric symptoms, such as difficulties with relationships and role functioning and other problems with living. Research indicates that individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia are more likely than other patient groups to be address as having poor insight. Gaining insight requires self-identifying as a person with a mental illness and developing a post-diagnosis identity that introduces new unfamiliar story lines to the personal narrative. Moreover, this transformation does not materialize exclusively in the individual. It is a public process involving the enactment of a post-diagnosis identity in a social environment that features significant stigma against schizophrenia (Williams 248). Gaining insight also requires self-efficacy, which is defined as the confidence one has in the ability to perform a behavior or specific task, and has been introduced as a crucial motivational factor for successfully carrying out social and everyday living skills. Few studies have addressed its role in functioning in schizophrenia. A study was designed to investigate whether degree of illness insight determined whether self-efficacy was a mediator of the relationship between two key illness features, negative symptoms and cognition, and function of skills. Results revealed that self-efficacy was only linked to measures of functioning skills when illness insight was intact. There was evidence of moderation of confounding effects, such that when self-efficacy was controlled, the relationship between negative symptoms and measures of everyday life skills became non-significant, but only The Disease Called Schizophrenia 6 when illness insight was again intact (Kurtz et al, 69). Several studies have shown plausible psychological and neurobiological mechanisms linking adverse experiences to psychosis, including induction of social defeat ad reduced self-value, sensitization of the dopamine system, changes in the stress and immune system, and accompanying changes in stress-related brain structures, such as the hippocampus and the amygdala. Limited evidence points to genes that are not specifically involved in psychosis but more generally in regular mood, such as the serotonin transporter gene, and the stress-response system (Van Winkel et al, 46). The immediate goals of treatment for a first episode of psychosis are to keep the patient safe by minimizing the risk of violence and suicide, and to establish an alliance that will promote compliance with treatment. Patients who are severely psychotic will usually require psychiatric hospitalization, particularly if there is any risk of violence or suicide and if treatment is rejected. When patients are willing to initiate an anti-psychotic and appropriate supervision is assured, outpatient treatment may be sufficient. Treatment of schizophrenia always need to be with both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. Non-pharmacological interventions include counseling for patients and their family, psychological support, behavior treatment, social and cognitive rehabilitation, assistance in social and scholastic activities and family support. Pharmacological treatment is necessary for remission and control of positive and negative symptoms. Furthermore, proper pharmocotherapy can greatly increase the efficacy of psychosocial interventions. Practical guidelines for the management of specific clinical situations are the first phases and the long term approach to pharmacotherapy, the treatment refractorness and the use of Clozapine in youths, the agitated adolescent and the treatment of negative symptoms and of affective co-morbidity (Masi et al, 181). The experience with electroconvulsive therapy for a first episode of schizophrenia is very sparse and limited to patients whose reponse to medications are unsatisfactory. While clearly not the standard The Disease Called Schizophrenia 7 of care, ECT remains one last treatment option that could be considered in patients who fail to respond to medications and when all other interventions have been exhausted. Although the foundation of psychosocial treatment programs for first episode and early psychosis is still being developed, the established benefits of certain interventions, such as family psycho-education which is therapy based on the principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy seeks to reduce the distress and disability associated with the symptoms of coping skills for psychotic symptoms, normalize psychosis and restructure psychotic and dysfunctional beliefs about the self and about symptoms. Supported employment, social skills training and assertive community treatment suggest that these interventions will also benefit first episode populations. Although the majority of first-episode patients will achieve full symptomatic recovery with antipsychotic medication, most will not attain a fully functional recovery. Numerous comprehensive firstepisode programs combine low-dose anti-psychotic medication with a range of psychosocial treatments, such as assertive community treatment. Case management, group therapy and a continuum of in and outpatient services (Freudenrich et al, 201). Family therapies play a crucial role in aiding treatment and recovery simply because most patients are still living with their families or have returned to the family home after a crisis or hospitalization. By default, family members become the defacto treatment system for many patients. A substantial body of evidence suggests that family psycho-education programs are an effective treatment for reducing rates of relapse among individuals with chronic schizophrenia and early indications suggest that family education and behavioral family therapy also improve outcomes for first-episode patients. Elements of family interventions typically include some combination of psycho-education, communication-skills training, strategies to reduce high expressed emotion, and training in the identification of early warning signs and relapse prevention planning. Despite promising results of these interventions and the perceived benefits of participating, it remains a challenge to engage families The Disease Called Schizophrenia 8 in treatment and to maintain their involvement so that they receive adequate exposure to the associated benefit (Freudenreich et al, 207). The history of schizophrenia dates back to the 1200's where a hospital named Bethlehem, better known as Bedlam was founded. The patients were subjected to all manners of indignities that were savored by fee-paying audiences, and the treatments that were given were far from conventional. For example, physicians would cut the liver from a frog, fold it in a leaf and burn it in a pot, mixing the ashes with wine to administer to the patients, the patients also ate roasted mice as a cure (95). But thanks to the curious and brilliant minds that were soon to follow, we no longer have to treat patients who are diagnosed with schizophrenia in this barbaric manner. There is no cure for schizophrenia, but with therapy and anti-psychotic medication it can be managed. The Disease Called Schizophrenia 9 Works Cited Freudenreich, Oliver; Holt, Daphne J.; Cather, Corinne; Goff, Donald C.; (2007). “The Evaluation and Management of Patients with First-Episode Schizophrenia: A Selective, Clinical Review of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis.” Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 15(5), 189-211. Masi, Gabriele; Liboni, Francesca. (2011). “Management of Schizophrenia in Children and Adolescents.” Drugs, 71(2), 179-208 Yung, Alison R.(2011) “Risk, Disorder and Diagnosis.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(11), 915-919 Kurtz, Matthew M.; Olfson, Rachel H.; Rose, Jennifer. (2013). “Self Efficacy and Functional Status in Schizophrenia: Relationship to Insight, Cognition and Negative Symptoms.” Schizophrenia Research, 145(3), 69-74. Williams, Charmaine C. (2011). “Insight, Stigma and Post-diagnosis Identities in Schizophrenia.” Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 71(3), 246-256 Keskinen, E.; Muttunen J.; Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Maki, P.; Isohanni M.; Jaaskalainen E. (2013). “Interaction between parental psychosis and the risk factors during pregnancy and birth for schizophrenia – The Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study.” Schizophrenia Research, 145(1-3), 56-62. Van Winkel, Ruud; Van Nierop, Martine; Myin-Germeys, Inez; Van Os, Jim; (2013). “Childhood trauma as a cause of psychosis: Linking Genes, Psychology and Biology.” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(1), 44-51. Comer, Ronald J. Abnormal Psychology. New York: Worth Publishers, 2013. Print Kellaway, Jean. The History of Torture & Execution. New York: The Lyons Press, 2001. Print “Emil Kraepelin.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 3 April 2003. Web. 02 April 2013