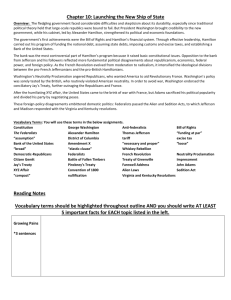

Chapter 5 Overview

advertisement

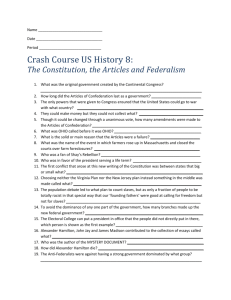

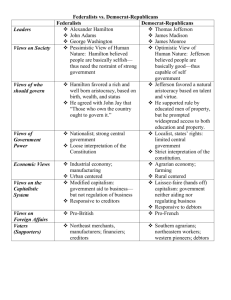

CHAPTER 5 The Federalist Era: Nationalism Triumphant CHAPTER OVERVIEW Inadequacies of the Articles of Confederation. Following the Revolutionary War, the United States struggled to achieve control of its own territory, to define the nature of its trade relationships, and to overcome economic difficulties at home. The Articles of Confederation proved inadequate to deal with these problems. Spain and England made it difficult for the United States to control its borders. In the southwest, the Spanish closed the Mississippi River to American commerce. Not only did Britain refuse to abandon several military posts just beyond the borders of the United States (as it had promised under the Peace of Paris), but it flooded the American market with low-priced manufactured goods. The government under the Articles of Confederation lacked the power to levy tariffs to limit imports. Moreover, the Articles required unanimous consent of the states, so Rhode Island’s opposition was enough to block a measure granting the Confederation power to levy a tariff. Daniel Shays’s “Little Rebellion.” Determined to pay off the state debt and to maintain a sound currency, the Massachusetts legislature levied heavy taxes. The resulting deflation led to foreclosures. In the summer of 1786, mobs in the western part of the state began to stop foreclosures by forcibly preventing the courts from holding sessions. Daniel Shays, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, led a march on Springfield, where the “rebels” prevented the state supreme court from meeting. The state sent troops, and the rebels were routed. However, the episode alarmed many prominent Americans, who regarded this episode as proof of the need for a stronger central government. To Philadelphia, and The Constitution. Most people wanted a stronger government, and the Articles of Confederation could not provide it. In 1786, delegates from five states met in Annapolis to discuss common problems. Alexander Hamilton, who advocated a strong central government, proposed calling another convention for the following year to consider constitutional reform. The meeting approved Hamilton’s suggestion, and all states except Rhode Island sent delegates to the convention in Philadelphia. The Great Convention. A remarkably talented group of delegates assembled in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation. The framers of the Constitution agreed on basic principles. There should be a federal system with independent state governments and a national government. The government should be republican in nature, drawing its authority from the people. No group within the society should dominate. The framers were suspicious of power and sought to protect the interests of minorities. The Compromises that Produced the Constitution. After voting to establish a national government, the delegates faced two problems: what powers should this government be granted and who would control it? The first question generated relatively little disagreement. Delegates granted the central government the right to levy taxes, to regulate interstate and foreign commerce, and to raise and maintain an army and navy. The second question proved more difficult. Larger states argued for representation based on population. Smaller states wanted equal representation for each state. The Great Compromise created a lower house based on population and an upper house in which each state had two representatives. The issue of slavery occasioned another struggle and another compromise. A slave was counted as three-fifths of a person for purposes of taxation and representation, and Congress was prohibited from outlawing the slave trade until 1808. The creation of a powerful president was the most radical departure from past practice. Only faith in Washington and the assumption that he would be the first president enabled the delegates to go so far. The delegates also established a third branch of government—the judiciary. The Founders worried that the powerful new government might be misused, so they created a system of “checks and balances” to limit the authority of any one branch. Ratifying the Constitution. The framers provided that their handiwork be ratified by special state conventions. This gave the people a voice and bypassed state legislatures. The new Constitution would take effect when nine states ratified it. Federalists (supporters of the Constitution) and Anti-federalists (their opponents) vied for support in the state conventions. It is difficult to distinguish between Federalists and Anti-federalists on the basis of economic status, social status, or even commitment to democratic ideals. Federalists tended to be more substantial individuals; Anti-federalists were more likely to be small farmers and debtors. In general, the Federalists were better organized than their opponents. The Federalist Papers brilliantly explained and defended the proposed new system. Most states ratified the Constitution readily once its backers agreed to add amendments guaranteeing the civil liberties of the people against encroachments by the national government. Washington as President. The first electoral college made George Washington its unanimous choice. Washington was a strong, firm, dignified, conscientious, but cautious, president. He was acutely aware that each of his actions would establish a precedent. Along those lines, he meticulously honored the separation of powers. Washington picked his advisors based on competence and made a practice of calling his department heads together for general advice. Within the cabinet, factions began to form around Jefferson and Hamilton. Congress Under Way. The first Congress created various departments and a federal judiciary. It also passed the first ten amendments to the Constitution. Known as the Bill of Rights, these amendments protected the freedom of speech, the press, and religion; reaffirmed the right to trial by jury; guaranteed the right to bear arms; prohibited unreasonable searches and seizures; and protected against self-incrimination. It also guaranteed due process of law. The Tenth Amendment reserved to the states powers not specifically delegated to the United States or denied to the states by the Constitution. Hamilton and Financial Reform. As one of its first acts, Congress imposed a tariff on foreign imports. Raising money for current expenses, however, was not so serious a problem as the large national debt. Congress delegated to Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, the task of straightening out the nation’s financial mess. Hamilton proved to be a farsighted economic planner. He suggested that the debt be funded at par and that the United States assume remaining state debts. Congress went along because it had no other choice. Southern states stood to lose, since they had already paid off most of their obligations from the Revolutionary War. Madison and Jefferson agreed to support Hamilton’s plan in exchange for the latter’s support for a plan to locate the permanent national capitol on the banks of the Potomac River. Hamilton also proposed a national bank. Like his other proposals, this one benefited the commercial classes. Congress passed a bill creating the bank, but Washington hesitated to sign it. Jefferson argued that the Constitution did not specifically authorize Congress to charter corporations or engage in banking. Hamilton countered that the bank fell within the “implied powers” of Congress. Washington accepted Hamilton’s reasoning, and the bank became an immediate success. Beyond the immediate financial crisis, Hamilton hoped to change an agricultural nation into one with a complex, self-sufficient economy. Toward that end, his Report on Manufactures issued a bold call for economic planning. A majority in Congress would not go so far, although many of the specific tariffs Hamilton recommended did become law. The Ohio Country: A Dark and Bloody Ground. Western issues continued to plague the new country. The British continued to occupy their forts, and western Indians resisted settlers encroaching on their hunting grounds. When white settlers moved into the land north of the Ohio River, the Indians drove the whites back. Westerners believed that the federal government was ignoring their interests. Compounding their discontent was the imposition of a federal excise tax on whiskey. The tax fell especially hard on westerners, who not only drank heavily but turned much of their grain into spirits to cope with the high cost of transportation. Resistance to the tax was especially intense in western Pennsylvania. Revolution in France. The French Revolution and subsequent European wars affected America. The Alliance of 1778 obligated the United States to defend French possessions in the Americas; however, with the British in Canada and the Spanish to the west and south, belligerence entailed grave risks. Washington issued a proclamation of neutrality. France sent Edmond Genet to the United States to seek support. In flagrant violation of American neutrality, Genet licensed American vessels as privateers and commissioned Americans to mount military expeditions against British and Spanish possessions in North America. Washington requested that France recall Genet. The European war increased demand for American products, but it also led both France and Britain to attack American shipping. The larger British fleet caused more damage. American resentment flared, but Washington attempted to negotiate a settlement with the British. Federalists and Republicans: The Rise of Political Parties. Washington enjoyed universal admiration, and his position as head of government limited partisanship. However, his principal advisors, Jefferson and Hamilton, disagreed on fundamental issues, and they became leaders around whom political parties coalesced. Jefferson’s opposition to Hamilton’s Bank of the United States became the first seriously divisive issue. Disagreement over the French Revolution and American policy toward France widened the split between parties. Jefferson and the Republicans supported France; Federalists backed the British. 1794: Crisis and Resolution. Several events in 1794 brought partisan conflict to a peak. Attempts to collect the whiskey tax in Pennsylvania resulted in violence. In July, 7,000 rebels converged on Pittsburgh and threatened to burn the town. Only the sight of federal artillery and the liberal dispensation of whiskey turned them away. Washington was determined to enforce the law and mustered a large army. He marched westward, but, when he arrived, the rebels had dispersed. This, coupled with the defeat of the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, helped pacify the west. Jay’s Treaty. Washington sent John Jay to negotiate a treaty settling differences with England. Although American indebtedness to England and the fear of a Franco-American alliance inclined the British to reach an accommodation with the United States, recent British victories in the war with France made them less disposed to make concessions. Thus, Jay obtained only one major concession. The British agreed to evacuate the posts in the west. They rejected, however, Jay’s attempts to gain recognition of neutral rights on the high seas. For his part, Jay agreed that America would not impose discriminatory duties on British goods and that America would pay pre-Revolutionary debts. The terms of the treaty raised a storm of opposition at home. 1795: All’s Well That Ends Well. Washington decided not to repudiate Jay’s Treaty, and the Senate ratified it in 1795. Jay’s Treaty became the basis for regularization of relations with Britain. Perhaps as important, Spain, fearing an Anglo-American alliance, offered the United States free navigation of the Mississippi and the right of deposit at New Orleans. The treaty that formalized this arrangement, known as Pinckney’s Treaty, also settled the disputed boundary between Spanish Florida and the United States. The agreements with European powers ended, for the moment, European pressure on the region beyond the Appalachians. This, along with the Treaty of Greenville, signed with the Indians after the Battle of Fallen Timbers, opened the west to settlement. Before the decade ended, Kentucky and Tennessee became states, and the Mississippi and Indiana territories were organized. Washington’s Farewell. The settlement of western and European problems did not end partisan conflict at home. Although Washington remained a symbol of national unity, he usually sided with Hamilton on issues of finance and foreign policy. At the end of his second term, Washington decided to retire. In his farewell address, he warned against partisanship at home and permanent alliances abroad. The Election of 1796. In spite of Washington’s warning against partisanship, his retirement opened the gates to partisan conflict. In the race to succeed Washington, Jefferson represented the Republicans, but the Federalists considered Hamilton too controversial. The Federalists therefore nominated John Adams for president and Thomas Pinckney for vice-president. Adams won, but partisan bickering split the Federalist vote for vice-president, so Jefferson received the second highest total and therefore became vice-president. The Federalists continued to quarrel among themselves, and Adams, although honest and able, was also caustic and brutally frank. He could not unite a bickering party. The XYZ Affair. In retaliation for Jay’s Treaty (and also to influence the election), the French attacked American shipping. These attacks continued after Adams took office. Adams sent a commission to France to negotiate a settlement. The mission collapsed when three French agents (X, Y, and Z) demanded a bribe before making a deal and the commissioners refused. Adams released the commissioners’ report, which caused a furor. The report embarrassed the Republicans; and Congress, controlled by the Federalists, abrogated the alliance with France and began to make preparations for war. Although a declaration of war would have been immensely popular, Adams contented himself with a buildup of the armed forces. The Alien and Sedition Acts. Federalists feared that Republicans would side with France if war broke out. In addition, refugees from both sides of the European war flocked to the United States. Partly out of fear of subversion and partly in an effort to smash their political opponents, Federalists pushed a series of repressive measures through Congress in 1798. The Alien Enemies Act empowered the president to arrest or expel aliens in time of declared war; and the Sedition Act made it a crime “to impede the operation of any law,” to instigate insurrection, or to publish “false, scandalous and malicious” criticism of government officials. As the election of 1800 neared, Federalists attempted to silence leading Republican newspapers. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolves. Jefferson did not object to state sedition laws, but he believed that the Alien and Sedition Acts violated the First Amendment. He and Madison drew up resolutions arguing that the laws were unconstitutional. Jefferson further argued that states could declare a law of Congress unconstitutional. Neither Virginia nor Kentucky tried to implement these resolves; Jefferson and Madison were in fact launching Jefferson’s campaign for president, not advancing an extreme theory of states’ rights. Taken aback by the American reaction, France offered negotiations, and Adams accepted the offer. Adams resisted strong pressure from his party for a war. Negotiators signed the Convention of 1800, which abrogated the Franco-American treaties of 1778.