2005-06 Hunt Grant Research Report

Perceptions of Graduate Admission Directors: Undergraduate Student Research Experiences:

"Are All Research Experiences Rated Equally?"

Judith Correa Kaiser, PhD, Andrew J. Kaiser, PhD, Nick J. Richardson, and Edward J. Fox

St. Ambrose University (IA)

Application and acceptance rates for PhD and PsyD clinical and counseling programs in

psychology show that these programs are highly competitive. Knowing which variables graduate

admissions committees deem important is critical for undergraduate faculty advisors to inform

these students of what graduate programs want from their applicants in order to be chosen for

this field of study. The primary goal of this study was to find information on how different types

of undergraduate research experiences and students' other activities were rated by 237 programs'

graduate admissions directors, chairpersons, or their designees. Four of 39 variables were shown

to be statistically significant and highly ranked by these participants. All 4 variables have one

thing in common: publication or presentation of research in a referred journal or regional

conference.

Examination of the application and acceptance rates for PhD and PsyD clinical and counseling

programs in psychology shows that these programs are highly competitive (American

Psychological Association [APA], 2005; Mayne, Norcross, & Sayette, 2006). As faculty

members who teach and advise undergraduate psychology majors who are primarily interested in

these competitive graduate programs, knowing which variables graduate admissions committees

deem important is critical. To inform these undergraduates of the factors graduate programs look

for in applicants and the importance these programs give to these factors, each year the APA

publishes the guidebook, Graduate Study in Psychology (APA, 2005). In addition, books,

research articles, and other publications (e.g., Eye on Psi Chi) provide undergraduate students

interested in applying to graduate schools recommendations on what to do to increase the

likelihood of being seriously considered for these very competitive programs (APA, 1997; KeithSpiegel, Tabachnick, & Spiegel, 1994; Mayne et al., 2006; Walfish & Turner, 2006).

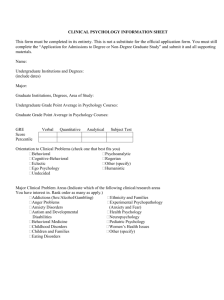

In general, students who apply to graduate programs in psychology are evaluated on various

objective and subjective criteria. Objective criteria include Grade Point Average (GPA), scores

on the Graduate Record Examination (GRE), and in some cases, the curriculum of study

completed (APA, 1997; Keith-Spiegel et al., 1994). Subjective criteria evaluated are letters of

recommendation, research experience, and autobiographical statements or statements of purpose

(APA, 1997; Blashfield, Keeley, Burgess, & Everett, 2005; Keith-Spiegel et al.; Norcross,

Hanych, & Terranova, 1996; Walfish & Turner, 2006).

A body of research has shown that among the subjective, or second-order, criteria used by

graduate selection committees to rate applicants, students' research experiences are rated as some

of the most important (APA, 2005; Cashin & Landrum, 1991; Keith-Spiegel et al., 1994;

Landrum, Jeglum, & Cashin 1994; Mayne et al., 2006; Walfish & Turner, 2006). Because of

these findings, researchers suggest that to increase a student's competitiveness for acceptance to

psychology graduate programs, undergraduate programs should provide more research

opportunities (Keith-Spiegel et al.).

In a study conducted in 2005, Perlman and McCann assessed students' research experiences in

undergraduate psychology program curricula. They found of the 203 undergraduate psychology

programs surveyed, 72% had a research experience course as part of their program requirements.

Moreover, these researchers found that 88% of departments offered a class with structured

research experiences, and 90% of the departments allowed students to conduct individual

research projects. Given the high percentages of undergraduate programs requiring research

experience, one would expect that most psychology students with hopes of attending graduate

school would have presented or published some research by the time they graduated with their

bachelors' degrees. However, it seems that most students did not take advantage of their

experiences to publish or present. Ferrari and Appleby (2005) surveyed a random sample of Psi

Chi undergraduate students who graduated with psychology degrees and found that although the

majority of the students had completed research projects, most had not presented any research in

conferences nor published.

It is possible that part of the reason for not publishing their undergraduate research is the high

rejection rates from most psychology journals. Powell (2000) reported that between 50% to 90%

of all research articles submitted for publication are rejected. However, according to this author,

acceptance rates for undergraduate conferences and undergraduate journals are higher;

nevertheless, these venues are not viewed as prestigious as the ones for professional researchers.

Differences in prestige should not be surprising because they are found even among state,

regional, and national conferences and peer-reviewed journals.

A question that might influence advisors' and their students' decisions to submit research to

undergraduate journals is "How do graduate selection committees rate this type of research

experience when evaluating students for entrance into their programs?" Several studies have

been conducted exploring this question. Ferrari and Davis (2001) found that faculty members

from research universities did not view these undergraduate publications favorably. Similarly,

Ferrari and Hemovich (2004) found that directors of graduate psychology programs did not view

publications in undergraduate student journals as being a significant factor for acceptance to their

graduate schools.

Thomas, Rewey, and Davis (2002) posed a similar question to faculty advisors of students

who had published in the Psi Chi Journal of Undergraduate Research. The results of this study

indicated that faculty advisors believed publications in the Psi Chi Journal were viewed

positively by graduate school selection committees. Furthermore, these researchers found that

the faculty advisors indicated that if they were part of a graduate school selection committee, this

type of publication would increase a student's likelihood of being accepted into their graduate

program.

Thus, the literature consistently shows it is important for undergraduate students to possess

research experiences (e.g., Ferrari & Davis, 2001; Ferrari & Hemovich, 2004; Keith-Spiegel et

al., 1994; Mayne et al., 2006; Walfish & Turner, 2006). However, when it comes to applying to

competitive graduate programs, graduate school selection committees seem to rate the value of

undergraduate research experiences for students' admittance to their program in different ways

(Ferrari & Davis; Ferrari & Hemovich).

The primary goal of this study was to examine how different types of undergraduate research

experiences were rated by graduate program directors (or the appropriate admission persons)

when making decisions about students' admittance to their programs. Additionally, we were

interested in obtaining information about how students' other activities (subjective criteria) were

rated by program directors from these competitive programs.

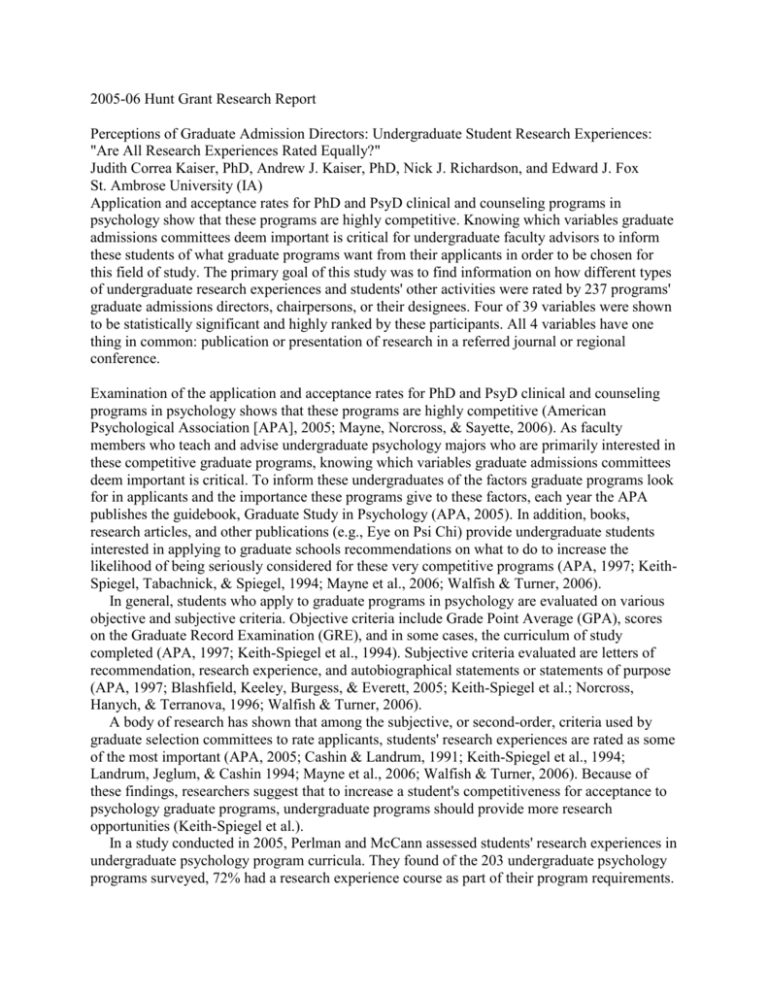

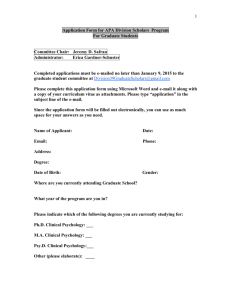

METHOD

Questionnaires about admission to their graduate programs were sent to the directors or

chairpersons (or their designees) of the 237 APA-approved clinical or counseling PhD or PsyD

programs. These psychology graduate schools were selected from the APA's Graduate Study in

Psychology, 2006 Edition (2005). After the 237 graduate schools had been identified using this

book, the current director, or chairperson, and the school's current address were confirmed by

accessing the graduate school's website.

The questionnaire used in this study was developed by the researchers and followed a format

similar to the questionnaire developed in the research conducted by Keith-Spiegel et al. (1994). It

consisted of the following scenario and a series of responses which were rated on a Likert-type

scale of 1 (not important) to 5 (extremely important):

Imagine that you have an excellent pool of applicants for your graduate program. These

applicants all have high GPAs (3.7 or above on a 4.0 scale), high GRE scores, very good

interviews, and strong letters of recommendation. Please rate the items listed below in terms of

their importance in assisting you to make your final determination of who gets accepted to your

program.

Each director or chairperson (or appropriate designee) received a letter explaining the

research and an informed consent form along with the questionnaire. Included in this letter was

the link that program officials could access if they preferred to complete the questionnaire

online. The online questionnaire was made available on a secured website attached to the St.

Ambrose Psychology Department's homepage. Both the physical and the online versions of the

questionnaire contained identical content.

After 4 weeks, all 237 graduate school representatives received an email message explaining

the purpose of the survey with the link to access it online or thanking them for their participation.

Because our study allowed for anonymous responses, we could not know which individuals had

completed the questionnaires; thus, all program directors received the email. Though it was not

guaranteed that directors would not respond to the paper version and the Internet version, we

believed that these graduate personnel were too busy to fill in more than one questionnaire. Data

collection ended two weeks after the reminder email message was sent.

RESULTS

Of the 237 surveys sent, 71 questionnaires were completed: 40 by mail and 31 by use of the

website. The return rate was 30%.

The means and standard deviations of the ratings for each item are presented in Table 1 in

order of most important item considered for program admission to least important.

A Chi Square Goodness of Fit Test was performed on each variable using as the comparison

distribution an equal distribution across the five levels of importance. To compensate for inflated

Type 1 error rate due to multiple analyses, an alpha of .01 was used. All but nine of the variables

reached statistical significance (see Table 1). The low mean ratings that were statistically

significant for many of the variables suggested that program directors do not view these

experiences as important for entrance in graduate school. Graduate school officials did rate some

experiences as important, however. More importance was given for program admittance to four

of the 39 variables. Only findings that were both statistically significant at an alpha of .01 or less

and had a mean rating of 3.5 or larger (where 5 is the highest rating) were considered as the most

important experiences that could lead to graduate school acceptance.

Table 1 shows, in order of importance, the four undergraduate research experiences that met

the criteria of being rated as very important or extremely important (and statistically significant)

for the respondents to make a final decision to accept the students into their program. First was

undergraduate research experience that led to a publication in a refereed journal, χ2(4) = 36.95, p

<.01; M = 3.99. Thirty percent of the participants considered that experience as very important

and 42% viewed it as extremely important for entrance in their graduate programs. The other

three undergraduate experiences that met both statistical significance and received a mean score

of 3.5 or larger were: publishing of their senior thesis, χ2(4) = 27.73, p <.01; M = 3.84 (35% of

the participants rated it as very important and 33% as extremely important); being a first author

in a publication in a refereed journal, χ2(4) = 37.80, p <.01; M = 3.83 (rated by 21% as very

important and 47% as extremely important), and giving a paper presentation at a regional

conference, χ2(3) = 17.29, p <.01; M = 3.54 (rated by 19% as very important and 23% as

extremely important).

Post-hoc Chi-Squared Tests of Independence were performed on each item to examine the

importance respondents from different program types gave to the different undergraduate

experiences. That is, were experiences rated differently depending on the type of the raters'

program (PhD clinical vs. PhD counseling vs. PsyD clinical)? Although the analysis produced

some interesting preliminary findings, these tests could not be interpreted due to variables having

numerous cells with less than five observations.

The second goal of this study was to assess how graduate program directors viewed student

applicants' other activities or experiences obtained in undergraduate school. Table 1 shows that

although many of these variables reached statistical significance, none of them met the mean

values given to research activities. Only two of the variables, number of statistical and research

courses taken and prestige of undergraduate institution, received a mean value of 3.0 or larger.

For the "number of statistical and research courses taken," 43% of the respondents rated it as

very important or extremely important for admittance into their program. For the variable

"prestige of the undergraduate institution from where the student graduated," 31% of the

respondents rated it as very important or extremely important.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to find information on how graduate program directors rated

different types of undergraduate experiences, especially research, when making decisions about

students' admittance to their programs. Though research experience for undergraduate students is

highly valued when admission decisions are made, apparently not all experiences are equally

important. Given the return rate of 30%, the advice given to students should be taken with

caution. However, the four highest ranked variables from our respondents do seem to be quite

impressive for an undergraduate student to complete. All four variables have one thing in

common: publication or presentation of research in a refereed journal or regional conference.

Additionally, it seems that being primary author will make you stand out from your

undergraduate peers. While research experiences were expected to be most important, we were

also interested in obtaining information about how graduate program directors rated other

subjective criteria. It appears that these other experiences were rated lower than research

publications and presentations. The reason for these ratings is not clear. One possibility is that

these experiences are not important because graduate directors expect all applicants to have had

these experiences.

To answer the question "Are all research experiences rated equally?"the answer appears to be

"No." However, a few experiences, research or otherwise, appear to impact graduate admissions

decisions. Based on these findings, faculty advisors need to let students know that although

publications in undergraduate student journals help improve their research skills, gain insight

into the scientific research process, and learn more about the publication process (Thomas et al.,

2001), they do not give students an advantage for entrance in competitive graduate programs.

Thus, students should aim for those four experiences, however, credit is still given for other

research work and experiences.

References

American Psychological Association (1997). Getting in: A step-by-step plan for gaining admission to graduate school in

psychology. Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association (2005). Graduate study in psychology, 2006 Edition. Washington, DC: Author.

Blashfield, R., Keeley, J., Burgess, D., & Everett, D. (2005, Fall). An apocryphal email exchange about admission to clinical

psychology graduate programs. Eye on Psi Chi, 10(1), 16-17; 34.

Cashin, J. R., & Landrum, R. E. (1991). Undergraduate students' perceptions of graduate admissions criteria in psychology.

Psychological Reports, 69, 1107-1110.

Ferrari, J. R., & Appleby, D. C. (2005, Winter). Alumni of Psi Chi: Does "membership have its advantage" on future

education/employment? Eye on Psi Chi, 9(2) 34-37.

Ferrari, J. R., & Davis, S. F. (2001, Winter). Undergraduate student journal: Perceptions and familiarity by faculty. Eye on Psi

Chi, 5(1), 13-17.

Ferrari, J. R., & Hemovich, V. B. (2004). Student-based psychology journals: Perceptions by graduate program directors.

Teaching of Psychology, 31, 272-275.

Keith-Spiegel, P., Tabachnick, B. G., & Spiegel, G. B. (1994). When demand exceeds supply: Second-order criteria used by

graduate school selection committees. Teaching of Psychology, 21, 79-81.

Landrum, R. E., Jeglum, E. B., & Cashin, J. R. (1994). The decision-making processes of graduate admissions committees in

psychology. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 9, 239-248.

Mayne, T. J., Norcross, J. C., & Sayette, M. A. (2006). Insider's guide to graduate programs in clinical and counseling

psychology. New York: Guildford Press.

Norcross, J. C., Hanych, J. M., & Terranova, R. D. (1996). Graduate study in psychology: 1992-1993. American Psychologist,

51, 631- 643.

Perlman, B., & McCann, L. I. (2005). Undergraduate research experiences in psychology: A national study of courses and

curricula. Teaching of Psychology, 32, 5-14.

Powell, J. L. (2000, Winter). Creative outlets for student research or what do I do now that my study is completed? Eye on Psi

Chi, 4(20), 28-29.

Thomas, J., Rewey, K. L., & Davis, S. F. (2002, Winter). Professional development benefits of publishing in the Psi Chi Journal

of Undergraduate Research. Eye on Psi Chi, 6(2), 30-35.

Walfish, S., & Turner, K. (2006, Summer). Relative weighting of admission variables in developmental psychology doctoral

programs. Eye on Psi Chi, 10(4), 20-21.

Judith Correa Kaiser, PhD, has been a professor of psychology at St. Ambrose University (IA) in

Davenport for 12 years. She received her BS in psychology from Florida State University, MS

from University of Central Florida, and her PhD in clinical psychology from Florida State

University in 1994. She is currently licensed to practice psychology in Iowa and Illinois. Dr.

Correa Kaiser is on the board of the Iowa Psychological Foundation and is the advisor to the Psi

Chi chapter at St. Ambrose. She has been nominated twice as St. Ambrose University's

"Professor of the Year," winning that honor in 2001.

Andrew J. Kaiser, PhD, has been an associate professor of psychology and education at St.

Ambrose University in Davenport for 12 years. He received his BS in psychology from the

University of Oklahoma and his MS and PhD in clinical psychology from Florida State

University. He is a member of Phi Beta Kappa, Psi Chi, and the APA. Dr. Kaiser also acts as St.

Ambrose University's ADA compliance officer and was a founder and past-president of the

Illinois/Iowa Association for Higher Education and Disability. He also developed the curriculum

for St. Ambrose University's Forensic Psychology Degree Program.

Nick J. Richardson, BA, is a 2006 graduate of St. Ambrose University's Forensic Psychology

Program. He participated in numerous volunteer and research opportunities studying the Scott

County Iowa Jail Programs. He won the award for St. Ambrose University's 2006 Outstanding

Psychology Major. He hopes to complete his doctoral degree in forensic psychology and is

currently working for the Center for Alcohol and Drug Services and the Seventh Judicial

Circuit's Department of Correctional Service's residential center.

Edward J. Fox, will complete his BS in psychology and English at St. Ambrose University in

2007. He is a veteran of the United States Army, currently working for the Department of

Homeland Security, and hopes to complete his doctorate in Neuroscience.

____________________________________________

Winter 2007 issue of Eye on Psi Chi (Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 22-24), published by Psi Chi, The

National Honor Society in Psychology (Chattanooga, TN). Copyright, 2007, Psi Chi, The

National Honor Society in Psychology. All rights reserved.