Staying Positive in Negative Times

advertisement

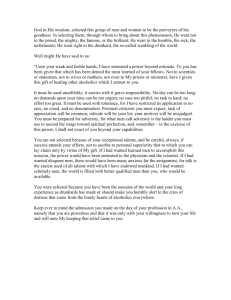

After reading the article “Staying Positive in Negative Times”, consider the questions at the end related to the six energy sources: Personal Values, Personal Efficacy, Emotional WellBeing, Spiritual Well-Being, Physical Well-Being, and Personal Support Base. Select two questions to discuss in your blogs. The first question should be one that speaks to an area that you believe is a strength of yours. The second question should be one that speaks to an area that you need to nurture in order to be a resilient leader. Staying Positive in Negative Times Jerry L. Patterson and Janice H. Patterson All leaders occasionally find themselves looking at adversity. How can you see your way through? How can school leaders learn to sustain positive energy in negative times? How can they find enough inner positive strength to empower other leaders, who in turn support them in nurturing energy throughout the school culture? One key to claiming this positive attitude? Resilience. Resilience is not about merely surviving. It's about emerging from life's storms stronger than before. A resilient leader recovers, learns, and grows stronger in the face of adversity. In our research, we asked 67 nationally recognized school leaders for their feedback about the importance of a list of items we had identified, through a review of literature in the school leadership field, as important to successful leadership. We pinpointed essential skills that leaders committed to sustaining resilience in the face of adversity must demonstrate. One of those skills was the ability to generate positive energy. How Positive Leaders Think In physics, energy refers to the capacity to do work. Our understanding of positive energy has its roots in the field of positive psychology. This new discipline is anchored in a set of core psychological constructs that describe how individuals and organizations can focus on assets without squandering energy worrying about liabilities.1 Positive energy begins with positive thinking. Adversity is inevitable, but we have some control over how we think about adversity. Some leaders choose to see the glass as half empty and communicate their pessimism to others. Imagine a principal announcing to her staff, "Now that we are mired in the mud of severe budget cuts, our programs will suffer big time." This way of thinking saps the energy out of the leader herself. In turn, it creates a whirlpool effect that drains energy from the entire school. A more positive school leader would not view having her budget slashed as the problem. She would view the cuts as the reality. The core problem would become, How can I find energy to move ahead in the face of the reality this crisis presents? Positive leaders shift their thinking from if only (…we didn't have budget cuts) to how can we? (…mobilize the resources we have to get through this in a healthy way). Positive leaders are not in denial. They want to know the unvarnished reality they confront and the obstacles in their way. But they choose to focus energy on the positive side of a negative situation because they know they can influence the future. Of course, even optimistic leaders sometimes expend negative energy when adversity strikes. One school leader asked us, "When bad things happen, isn't it OK to wallow in self pity for a while?" Our response: "Of course. What distinguishes resilient from nonresilient leaders is how long you wallow." Resilience is a long-term construct. Most of us occasionally fall into the victim trap when things get rough and we begin to feel the energy that fuels us leaking out. However, resilient leaders quickly plug the leaks before the fuel level gets too low. Four sources of strength help resilient leaders accomplish that crucial conversion: values, personal efficacy, personal well-being, and a support base. Four Ways to Fill the Tank Tap Personal Values Resilient leaders draw strength from their ability to clarify and articulate what matters most to them rather than reacting to events. Under tough conditions, event-driven leaders react to every external force. They are battered by the political winds of the moment and they let these storms cause abrupt changes in their direction. Value-driven leaders have ballast, a core set of beliefs that provides stability. They are motivated because they are using energy to realize cherished values. An elementary school principal in a high-poverty Houston neighborhood talked about how he goes back to his core values and priorities: In these tough times, I feel constantly bombarded by pressure at the district and state level to implement the latest fads. … At the same time, my highest priority is to spend my energy and the staff's energy on what matters most to us, student achievement. So how do I handle it? I serve as buffer from all of the unnecessary distractions hurled at us. For instance, I screen the "great ideas" presented to us at principals' meetings. I don't take an idea back to the school until I make certain it has legs. Too many times we spend our energy worrying about how we are going to make room for this latest idea on an our over-filled plate. … I become more resilient by investing my energy in the positive goals of the school [and] I believe I contribute positively to our staff's energy by keeping central-office mumbo jumbo out of the classroom. Embrace Your Efficacy We define personal efficacy as a leader's competence and confidence to move ahead. An unanticipated crisis demands that leaders draw on energy they didn't plan on spending. When confronted by crises, resilient leaders rely on their belief that, using their own skills and the skills of their network, they can do whatever is needed. When a leader succeeds in times of stress, his or her personal efficacy grows stronger in preparation for the next challenge. New leaders can nurture confidence in their own leadership in several ways; risk taking is a good start. Teacher leaders are, inherently, risk takers. They step forward because they believe in themselves and the core values they hold. And they aren't afraid of setbacks. They dust themselves off and bounce back when faced with adversity. This builds their competence, and their peers often begin to look to them as informal leaders because of their credibility and expertise. A teacher leader in a small midwestern district told us how she helped the school weather three principal turnovers in five years. This latest turnover initially sapped our energy. But I have been here through each of the principal changes, and I am viewed informally as a leader among my colleagues. We have a strong culture and we have previously held together when other principals left. For example, we identified a team to handle the scheduling that fits our collaborative teaching concept. We agreed that the building support team would serve as the decision-making council until a new principal was oriented to our culture. This collective belief in ourselves allowed us to successfully deal with the ambiguity of changing leaders again. Nurture Personal Well-Being In our work with school leaders, we found that this source of positive energy was in short supply. In turbulent times, leaders tend to charge ahead and sacrifice themselves for the good of the organizational culture. Obviously, some circumstances demand short-term sacrifices in time, sleep, exercise, and reflection. But resilient leaders look beyond the short term. They know that the long-term health of an organization depends, in large part, on the health of its leaders. A director of secondary education in an Alabama school district described how he restored his emotional energy after the board fired the superintendent. This was someone personally very close to me. … He had been a leader for more than 10 years during my career as teacher, assistant principal, and central office administrator. I felt like a victim of politics and tried to hide both physically and emotionally. … The stress spilled over into my personal life. … It affected my physical and emotional health. After my physician sounded a wake-up call, I decided I had to personally engage and take action to avoid staying stuck in the victim role. Initially I began to listen more in situations that helped me understand the nature of power. I came to terms with the reality that power struggles exist … I realized, upon reflection, that I had been a rather emotionally isolated leader. … So now, for example, I have lunch with a couple of principals every now and then. Don't Play the Lone Ranger For years, the typical image of successful leadership, particularly male leadership, was the Lone Ranger. Leaders were considered weak if they depended on others for support or expertise. Today's leaders are more attuned to the organic nature of schools and everyone's need to rely on others. Most know that to maintain their own energy, they need a supportive climate—and that they need to take the lead in creating it. An urban high school principal discussed the steps she took in this regard: First, I personally modeled a culture of caring and support. I took the time to get to know teachers as individuals, with their own fears and dreams. … I [would] stop by the math classroom and ask about the family trip to explore colleges … or check with the custodian about his elderly father who was hospitalized. These weren't superficial conversations. They reflected my commitment to strengthen personal connections. Next, I encouraged staff to step in and reach out. One group organizes birthday recognition activities for staff members. Impromptu committees form to provide support when families are in need. … We formalized ways to support teachers who are struggling in their teaching assignment. Specifically, we implement support teams of experienced teachers who devote time to help where expertise is needed. Resilient leaders draw on supports outside their school—mentors, colleagues who have survived comparable adversity, compassionate family members and friends, or professional networks—when adversity strikes. They aren't timid about turning to their base for help. Tools to Convert Energy into Action The good news is that leaders have four different fuel sources for keeping energy positive and high in tough times. The bad news is that it's just potential energy that can be ignored or expended unwisely. Energydeveloping skills are necessary but not sufficient to create resilient leaders. To turn negative circumstances into positive outcomes, leaders must convert energy into actions that make the envisioned future a reality. Our research uncovered four actions that sustain positive energy: Demonstrate perseverance, refusing to be derailed by outside pressures or distractions. Model adaptability, remaining open to new and creative ways to get through adversity. Leaders aren't energized by routine; they recharge their batteries by letting go of ineffective practices in exchange for something new and better. Courageously make decisions that are consistent with personal values. Assume personal responsibility for actions, including mistakes that contributed to the adversity in the first place. Converting energy into action is a long-term mission. It requires that the leader understand, at a deep level, what constitutes leader resilience; act on what matters most in terms of personal values; and create an organizational culture that nurtures positive energy. The first step is to look inside yourself and get a sense of the skills you already possess for nurturing resilience and the skills you need to strengthen or to seek among others in your network. Answering the reflective questions will help you get a handle on how well you now draw on the various sources of energy as you lead. Take time to review your career and record details of times you feel you succeeded—or faltered—in keeping yourself and your culture strong. Another good tool is the Leader Resilience Profile, a free Webbased survey we recently developed that measures resilience strengths in nine areas. You will receive a score for each strength, which provides you a customized profile reflecting your resilience. Both the questions and the Leader Resilience Profile are professional development tools to help you know your relative strengths so you can call on these strengths in the future, rather than assessments of your capability. You can also use both tools to gather feedback from peers about their perceptions of your strengths. We have focused on positive energy in leaders because our experience in working with schools across the United States has reinforced a fundamental point: The overall level of resilience a school leader demonstrates is reflected in the collective resilience of the faculty and the school culture. Particularly in tough times for schools and the education field, leaders have an obligation to the groups they serve to nourish their own personal physical, emotional, and spiritual vitality. How Well Do You Nurture Positive Energy in Tough Times? Energy Source: Personal Values To what extent have I privately clarified and publicly articulated my core values? When have I taken leadership actions consistent with my values? What can I point to that demonstrates that I make value-driven decisions in the face of strong opposition? Energy Source: Personal Efficacy When have I offset my relative weaknesses by turning to others who have strengths in the skills required? What evidence from my past performance shows I possess knowledge and skill to lead in tough times? When have I maintained a composed and respected leadership presence in the midst of adversity? Energy Source: Emotional Well-Being Can I emotionally accept aspects of adversity that I can't influence in a positive way? Do I understand my emotions in times of adversity and how these emotions affect my leadership performance? How successful have I been in controlling my emotions before I say or do something I might regret? Energy Source: Spiritual Well-Being How have I gained strength from my connection to a higher purpose in life? How have I expressed spiritual gratitude for the opportunity to serve others? Have I turned to personal reflection and introspection to steady myself during adversity? Energy Source: Physical Well-Being Have I let adversity disrupt my long-term focus on a healthy lifestyle? What strategies have worked for me in managing my time devoted to rest and recovery? Have I found healthy ways to channel my physical energy as a stress reliever? Energy Source: Personal Support Base What have I learned from others who faced similar circumstances? Have I made myself vulnerable enough to involve those I trust in discussions about my doubts or fears? Have I actively sought to learn from role models who demonstrate a strong track record of resilience? Endnote 1 For a comprehensive discussion of this subject, see Dutton, J. E., Quinn, R. E., Cameron, K. S. (2003). Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. Jerry L. Patterson is Professor in Educational Leadership at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a former high school teacher and superintendent; jpat@uab.edu. He is the coauthor with George Goens and Diane Reed of the forthcoming book Resilient Leadership for Turbulent Times (Rowman and Littlefield, 2009). Janice H. Patterson is Associate Professor in Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a former elementary school teacher; janhpat@uab.edu. Copyright © 2009 by ASCD