Mason & Stephenson: Chapter II

advertisement

Mason & Stephenson: Chapter II

Judicial Review

At the time of the Founding there was a very serious question concerning who would be the

ultimate interpreter of the Constitution. Some believed that each state would be able to

decide for itself which laws were constitutional and which were not. Some believed that

in our system, as in the British, the national legislature would decide. Still others argued

that each branch should decide for itself within its own sphere, what embodied

constitutional action.

Many, probably most, of the national leaders, felt that the national judiciary, in general, and the

Supreme Court, in particular, should determine the proper constitutional restraints on

government. [READ Supremacy Clause (Art. VI, para. 2) (page 711*)]. There

seemed to be something of a consensus at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and

during the ratification debates which followed, that the national judiciary would be

charged with this task (although the evidence is not completely unambiguous).

Although there was considerable disagreement on exactly how the judiciary would

exercise the power of judicial review, both supporters and detractors of the

Constitution assumed the existence of some form of judicial review.

THE UNSTAGED DEBATE

WHO IS BRUTUS? [Not just Robert Yates, but what was his position on the Constitution?

Anti-federalist, opponent of the Constitution, and power in the central government (and

especially in the judiciary.)

Brutus is fully aware of the power of judicial review that exists (largely by implication in

the Constitution) and he greatly fears that power because the Supreme Court is to

be totally independent! [READ 57:1].

2

Brutus also recognizes that Court opinions will have the force of law [READ 57:2]

Similarly he is concerned that the judicial power is greater than the legislative as he sees

it [READ 58:3]

Finally, Brutus explicitly recognizes that the Supreme Court is THE Interpreter of the

Constitution! [READ 58:4]

WHO IS PUBLIUS? What is his position on judicial review? On a strong national government?

On a strong national judiciary?

Federalist No. 78: Publius responds to Brutus--The power of authoritatively interpreting

the constitution must be lodged somewhere in the central government, and the

judiciary is the "least dangerous branch."

[READ p. 59:1]

Publius, like Brutus, assumes the existence of judicial review under the

Constitution. [READ 59:2]

Publius also offers a justification for this interpretation. [READ 59:3]

Publius even foresees the role of the Supreme Court as the protector of the

rights of minorities, as well as the political rights of the

Constitution. [READ 60:4]

Although the founders assumed judicial review, and some state courts actually experimented

with it, the federal judiciary was hesitant to do much more than talk about it during their

first 15 years of existence.

3

In Hylton v. United States, 3 Dall. (3 U.S.) 171 (1796), the Court affirmed congressional

power to levy a carriage tax, and implicitly asserted the Court's power to nullify

congressional acts as well. (If the Court may judge positively, can it not

necessarily judge negatively?)

Later, in Ware v. Hylton, 3 Dall. (3 U.S.) 199 (1796), the Court upheld the provisions of a

federal treaty over state law. So what? If it can judge a treaty provision to be

valid, doesn't that imply that it can also judge it to be invalid?

CALDER v. BULL (1798) (342)

3 Dall. (3 U.S.) 386

[Calder v. Bull comes to the Court on a "writ of error." This is a common law process

issued from an appellate court to a lower court ordering it to send up a case for

review of a limited question of law. It is still used in some state courts, but has

not been available in federal courts since 1928. Today such a case would have to

be brought up on a cert. petition.]

This case is not most important for its ruling, but because two justices of the Supreme

Court engaged in a now famous debate over the limits of judicial review.

Facts: After Calder had prevailed over Bull in a probate court and the time for filing an

appeal had expired, the Connecticut legislature passed a law which gave the Bulls

a new hearing, in which the Bulls prevailed and Calder challenges the statute

creating the new hearing as being an ex post facto law.

4

Holding: The Court affirmed the validity of a Connecticut probate statute against charges

that it was the embodiment of an ex post facto law.

Basis: The Court rules that this is not an ex post facto law since it deals with a civil

rather than a criminal matter. [Are they correct? Yes, in tradition. We are

frequently subjected to retroactive laws in non-criminal matters. A prime

example is the income tax. For this year and most the federal tax rate is still not

firmly set and yet we have all been paying withholding taxes since January.]

We read this case primarily to see Justices Chase and Iredell debate the conditions under

which a court could strike down a legislative act.

Justice Chase contends that a law which is unjust cannot be given effect by the

judges. He would throw out laws which were not unconstitutional, but

were against the laws of nature and the social compact. [READ 342:4]

Chase goes out of his way to express his view that even if there were no

constitutional provision, an unjust law would be unconstitutional

[READ 342:1]

He says that the legislature in a free society is not omnipotent! [READ 342:2 &

342:3]

Although this case deals with an act of the state legislature, Chase makes it clear

that his remarks would include acts of Congress as well.

Justice Iredell's response is that a judge represents only one opinion of many as to what natural

justice is! [READ 343:1]

Iredell concedes a power of judicial review, but severely limits it [READ 343:2]

5

Iredell says that barring such a clear and urgent case the Court should avoid such actions!

[READ 343-344:3] He is presenting a practical as well as a theoretical reason for

his position.

In form, Iredell won the debate, but in fact and practice Chase won (based on almost 200

years of constitutional history, and especially the last 100 years).

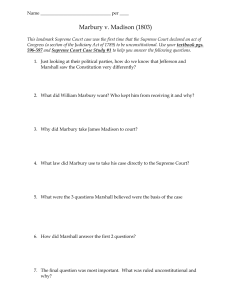

MARBURY v. MADISON (1803) (60)

1 Cr. (5 U.S.) 137

BACKGROUND: In the election of 1800 there was a fierce political struggle between the

Federalists, who were in power, and the Jeffersonian Republicans, who wanted to be.

The Federalists had been in control for twelve years, and Jefferson and his followers

found their policies to be unbearable.

In the election, the Republicans won decisive victories in both houses of Congress and

also won the presidency for Jefferson. In an effort to keep some control in

government, John Adams and the lame duck federal Congress created many new

judicial posts, and Adams filled them with loyal Federalists.

They had been nominated by Adams, confirmed by the Senate, and their commissions

had been signed by Adams and sent to the Secretary of State, John Marshall, for

application of the Seal of the U. S. and delivery to the appointees. While

Marshall did seal all of the commissions and deliver most of them, seventeen of

the commissions were not delivered to the appointees before Marshall left office.

Jefferson's new Secretary of State, James Madison, refused to deliver these

commissions upon taking office.

6

Among these new appointees whose commissions were undelivered were William

Marbury and three other new justices of the peace in Washington, D.C.

Under the provisions of the Judiciary Act of 1789, Marbury and his three

companions asked the Supreme Court to issue a writ of Mandamus to Madison in

exercise of its original jurisdiction (Mandamus was never sought from a lower

court.)

Although Marshall had been Secretary of State at the time of the appointments, he was

now Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, a last minute appointee himself!

Marshall did not disqualify himself from considering the matter (today a judge

would disqualify himself in such a situation). In fact, Marshall wrote the opinion

of the Court in the case. [It was not uncommon for a Judge or Justice to take part

in a case he had previously heard in those days--but this was different and was

more than a little unusual even then.]

The Opinion in Marbury v. Madison (61):

Marshall states that three questions need to be answered in this case to determine the

outcome:

1. Has Marbury a right to the office? [YES] [61:13]

2. If he has a right and it has been violated, do the laws afford him a remedy?

[YES (Almost identical to the first, since in law where there is a right

that has been violated, there is a remedy.)] [61:14]

3. Is he entitled to the remedy for which he applies? Depends on two things--the

nature of the writ applied for, and the power of the Court.

First, is the writ of Mandamus appropriate? Marshall says yes. [What is a

writ of Mandamus? Order from a court to a lower tribunal or other

government official to do his (non-discretionary) duty in a

particular matter.]

7

Second, can the Supreme Court issue a writ of Mandamus in the exercise

of its original jurisdiction in this matter? Under the Federal

Judiciary Act of 1789, the answer is yes [see 1:62]. In addition,

the Constitution places the whole judicial power in one Supreme

Court, and such inferior courts as Congress shall establish, and this

judicial power extends to all cases arising under the laws of the

United States. HENCE, some relief is available in the U. S.

judiciary, since the right arises under the laws of the U. S.

However, the Constitution also distributes some of this judicial

power saying "the Supreme Court shall have original

jurisdiction, in all cases affecting ambassadors, other public

ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be a

party. In all other cases, the Supreme Court shall have

appellate jurisdiction." [READ 2:62, 3:62] This case

involves original jurisdiction and Marshall says that the

legislative authority for the court to hear the case is at odds

with the language of the Constitution! What to do?

Can the Court be required to give an act of Congress which violates the Constitution the

force of Law? [READ 4:62]

To answer that question, it is only necessary to resort to the first principles of

American government: which are that, (1) the people have the right to

establish the government as they see fit and to make it permanent [5:62]

AND (2) the American people not only provided a framework of

government in the Constitution, but also spelled out the limits of

legislative action therein. It would be absurd to set limits on the

legislature that could be breached by mere legislative action. [6:62-63]

8

Marshall’s case for Judicial Review:

Clearly, if the Constitution has any meaning at all, the Constitution is superior to

acts of the Legislature. Marshall begins by giving the overview of this

position. [READ 7:63]

BUT, Must the Court enforce such a legislative act once the Congress has passed

it? [READ 8:63]. It seems absurd, but Marshall pursues it. It is in the

judicial province to say what the law is--to expound and interpret the law

[9:63].

Where the Constitution and the law conflict in Court, the Constitution

must prevail since it is superior law! [10:63] To deny this would

reduce constitutional governments to nothingness [11:63]

Marshall noted that the argument might be made that the Constitution is a

set of guidelines for the legislature and not the judiciary, and that it

is, therefore, for the legislature and not the judiciary to interpret the

Constitution. However, Marshall observes that a number of

provisions of the Constitution are directly addressed to the

judiciary (ie. ex post facto, the grounds for treason, etc.) The

framers obviously meant for the judges to read the Constitution!

The framers even required the judges to take an oath to support the

Constitution, he says. [Art. VI, para. 3 (p. 63)] If a judge cannot

be guided by the Constitution in the performance of his duties, then

it is a mockery to have him swear such an oath. Worse yet, if a

judge is bound to give force to unconstitutional acts of Congress

the oath is worse than a mockery.

Finally, the Supremacy Clause dictates that this Constitution and the laws

made pursuant to it are the supreme law of the land [Art. VI, para.

2] [READ 12:64].

9

Marshall concludes that no relief may be granted to Marbury by way of a writ of

Mandamus from the Supreme Court, because the statute empowering the Court to

issue such writs violated the Constitution and was void (in that provision).

Jefferson and Madison won the battle to keep Marbury and the others from receiving

their commissions, but Marshall won the war by asserting the right of the

Supreme Court to interpret and apply the Constitution (rather than the legislature

or the President).

[DOES MARSHALL AGREE WITH CHASE OR IREDELL ABOUT THE NATURE OF

JUDICIAL REVIEW?]

[CLEARLY THE FRAMERS AND MARSHALL INTENDED SOME SORT OF JUDICIAL

REVIEW, BUT DID THEY INTEND IT AS IT IS USED TODAY?]

NOTE: Constitutional law is largely based upon ambiguous sections of the Constitution, not on

the clear-cut ones!

Marshall's assertion of Judicial Review was not universally applauded (to say the least). He was

even attacked by other judges. Perhaps the best counterpoint was offered by Justice

Gibson of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 1825.

10

EAKIN v. RAUB (Pa. S.C., 1825) (64)

Facts are not important, this is a dissenting opinion, and is important only as a response to

Marshall [explain dissenting and concurring opinions]

Gibson announces at the outset that he will offer a challenge to Marshall's view of judicial

review.

Gibson says that the branches are equal, at least in the sense that each is superior in its

own realm and function. Accordingly, the legislature is the proper judge of the

legislative function. [1:65]

He asks how can there be true judicial equality (as Marshall claimed) if the judiciary can

only apply laws made by legislators?

Gibson notes (in a portion of the opinion which you don't have) that the fact that

the Courts are constitutionally created offices offers no aid! If it did, then

sheriffs, etc. would also be equal.

He claims that the framers provided for legislative checks without the doctrine of

judicial review, and if they had intended an additional check through

judicial review, they would have explicitly placed such a power in the

courts! [2:66]

Gibson also addresses the oath argument, saying that all government officials take

an oath. In addition, he notes that judges would not be doing any positive

acts in violation of their oaths when they construed and applied laws they

felt violated the Constitution. [66*, col. 1-2]

With regard to Marshall's general statement about the absence of judicial review

meaning an end to constitutional government, or limited government,

Gibson remains unconvinced. Paper does not assure the non-violation of

principles. [READ 3:66]

11

Gibson concluded that the proper response to legislative overstepping of

constitutional bounds is to throw the rascals out of office. [READ 4:67]

What about state laws? [READ 5:67]

In fact, the Supreme Court did not get around to striking down a state statute until 1809 in United

States v. Peters, 5 Cr. (9 U.S.) 115 (1809), and that involved a rather special statute

which purported to invalidate the orders of federal courts and prevent their enforcement

in Pennsylvania.

The first important declaration that a state statute was unconstitutional came in Fletcher

v. Peck, 6 Cr. (10 U.S.) 87 (1810), in which Marshall, writing for the majority,

declared an act of the Georgia legislature which purported to annul contracts

entered into by an earlier legislature, null and void, as a violation of the obligation

of contracts clause (Art. I, sect. 10). [case arising from the Yazoo Land frauds].

This was another of Marshall's landmark opinions.

However, Marshall would never again join in an opinion declaring an act of Congress

unconstitutional. In fact, the Court would invalidate more than thirty additional

state statutes before it would again declare an act of Congress unconstitutional.

In 1857, the Court's second invalidation of an act of Congress would come in the

infamous case of Scott v. Sandford, 19 How. (60 U.S.) 393 (1857), 15 L.Ed. 691

(67) [The Dred Scott Case]. I had you read the case to see the second time that

judicial review was exercised and so that you could see what a dramatic

expansion of the concept of judicial review this case made. We won't go over the

case in class. The case law is no longer valid (the Civil War and the amendments

which followed from it invalidated the decision) and the case is read only as an

historical relic, except for the impact it had on J.R. [Note that like the Marshall

Court, the Taney Court invalidated only one act of Congress--but it was a huge

one, the Missouri Compromise.]

12

POLITICAL QUESTIONS

The political question doctrine is a final way that the Court has of avoiding issues. This doctrine

was hinted at by Marshall's opinion in Marbury v. Madison (1803): "The province of the

court is, solely, to decide on the rights of individuals, not to inquire how the executive, or

executive officers, perform duties in which they have discretion. Questions in their

nature political, or which are, by the constitution and laws, submitted to the executive,

can never be made in this court."

The doctrine emerged in practice under C.J. Taney in the case of Luther v. Borden (1849). In

that case the Court declared that the decision of whether a state has a republican form of

government is a decision to be made by Congress and not by the courts! Case arose in

Rhode Island during Dorr's rebellion. Taney writes: "No one, we believe, has ever

doubted the proposition that, according to the institutions of this country, the sovereignty

in every State resides in the people of the State, and they may alter and change their form

of government at their own pleasure. But whether they have changed it or not, by

abolishing an old government, and establishing a new one in its place, is a question to be

settled by the political power. And when that power has decided, the courts are bound to

take notice of its decision, and to follow it." (Mason & Beaney, 6th Ed, p. 53).

Other areas identified as raising political questions are catalogued in Baker v.

Carr (1962) [204**].

In 1946, the USSC, in an opinion by Frankfurter, used the political question doctrine to

avoid ruling on the malapportionment of the Illinois congressional districts

[Colegrove v. Green (1946) (328 U.S. 549)].

13

In the 1960 case of Gomillion v. Lightfoot (364 U.S. 339) (a.k.a. the Tuskegee case), the

Court had held that where malapportionment was purposely done in order to

exclude a racial minority from the political process that the court could hear the

case and it was not a political question. In that case the city limits of Tuskegee

had been redrawn so as to exclude all but a few Blacks from the city voting area.

[One factor in distinquishing Colegrove, although not mentioned in the opinion,

was that the solicitor general had filed an amicus curiae brief which told the Court

that if they ordered reapportionment, the Justice Department would see that it was

enforced!] The ruling in Gomillion did not upset the Colegrove precedent

because the facts (of deliberate gerrymandering) could easily be used to

distinguish it (Also the challenge here was based on the 15th Am. right to vote!).

BAKER v. CARR (1962) (203)

369 U.S. 186

Court reverses its earlier stand that apportionment was a political question. [see

Colegrove]

Note that the problems in this case was created by urbanization, and the failure to

redistrict in light of population shifts (over a 60 year period). Because the

case did not involve deliberate gerrymandering Colegrove, not Gomillion,

would seem to control.

To solve the problem presented here the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment was ultimately invoked. [SEE 204:1] [The lower Court had

refused to hear the case on the basis of Colegrove and the political

question doctrine.]

However, before a court could reach the merits of the case, the problems of

jurisdiction and justiciability (political question) had to be addressed.

14

[ Brennan in the opinion of the court notes that had the plaintiffs in this case

invoked the Guaranty Clause it would not have helped them (Luther v.

Borden would still control) [SEE 204:2; 204:3]

The fundamental holding of the Court is that claims pressed on the basis of

political rights (ie. voting or running for office) do not necessarily raise

political questions which the Court cannot address! [In an omitted portion

of the opinion Brennan states, "The mere fact that the suit seeks protection

of a political right does not mean it presents a political question!" The

Court holds that since plaintiffs invoke the equal protection clause rather

than the Guaranty clause, this case is distinguishable from the other cases!

(Colegrove is distinguished, not overruled. Or perhaps it may be better to

say that Colegrove was overruled to the extent that it said that any

challenge to apportionment is a political question (a position which

Brennan says is a misunderstanding of Colegrove.)

The Court does not order Tennessee to reapportion, but remands the case to the

District Court for it to decide the matter on its merits! [A new approach to

such problems, which Clark does not like.]

Ultimately, Brennan's opinion does not explain why the Court changed its mind

here. In Baker, as in Gomillion, the Justice Department had filed an

amicus assuring the Court that its order would be enforced if it found

justiciability.

Frankfurter (who had written the Colegrove opinion) dissents out of a fear that the

Court will lose its support. [He was one of the last great advocates of

judicial restraint to serve on the Court] [READ 205*]

Harlan offers a similar dissent.

15

{What is Clark's point (concurring)? Although it is unclear here, Clark writes

urging the Court to decide the case here and now and not send it back to

the lower court. Most of the people of Tennessee are not represented, and

we are their last resort. He seems to want the court to decide the case here

and now and not send it back to the lower courts.}}

{Mason and Stephenson then move to an example of the recent status of judicial review. In two

editions of your casebook (11th & 12th ) they included a case called Missouri v. Jenkins

(1990). In that case the USSC held that it was beyond the scope of authority of a federal

district court to raise property taxes beyond state constitutional limits in a local school

district to fund court mandated programs designed to desegregate the school system. The

majority, in that case held that the district court could order the school district to raise

taxes, if necessary to fund its mandated programs, but could not raise the taxes itself.}

City of Boerne v. Flores (1997) (72)

521 US 507

FACTS: Congress enacted the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993 in response

to the Supreme Court’s decision in Employment Division v. Smith (1990). In Smith, the

Court had upheld the denial of unemployment benefits to two drug counselors who had

lost their jobs because of their ritual use of peyote (as a part of their religious practices in

the Native American Church) in violation of a general statute in Oregon banning the use

of illegal drugs, including peyote. Congress passed RFRA in an effort to impose on all

governmental officials in the U.S. a more “religion friendly” standard to be applied to all

cases arising under the “free exercise” clause of the First Amendment. The Catholic

Archbishop of San Antonio had applied for a building permit to enlarge a church in

16

Boerne. The permit was denied due to local zoning ordinances, and the Bishop

challenged the denial as a violation of RFRA. The District Court in Texas held that

Congress had exceeded its authority by enacting RFRA and in an attempt to take over the

interpretation and application of the “free exercise” clause of the Constitution. The Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reversed, and appeal was had to the USSC.

QUESTION: Is the RFRA an unconstitutional effort by Congress to “decree the substance of the

Fourteenth Amendment’s restrictions” on government?

ANSWER: YES!

REASONING: Justice Kennedy delivered the O.C.

Congress had claimed that the RFRA was merely an exercise of its authority under

section 5 of the 14th Amendment to enforce the provisions of that Amendment.

The Court holds that there is a difference between enforcing and changing the

substantive meaning of the rights in question. [READ 73:1]

The Court quotes extensively from Marbury v. Madison. [READ 74:2]

The Court then states that Congress attempted in the RFRA to create a test for

applying the “free exercise” clause that the Court had never used and was,

therefore, violating both separation of powers and the federal balance.

[READ 74-75:3]

UNSTAGED DEBATES

{As you can see President Jackson expresses extreme reservations about the binding nature of

judicial review on the other branches. Lincoln has reservations with regard to certain

issues being settled by the judiciary (expressed in his first inaugural address). These

17

remarks are obviously in reference to the Dred Scott decision.}

In Cooper v. Aaron the USSC (in an opinion signed by every justice during a special August

term of the Court) reasserts its position as expositor of the Constitution (in the case

involving the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas). [7677*] [See also 3 LEd 2d 18]

{What about Bork & Tribe? Obviously, there is some disagreement concerning the proper role

of original intent in constitutional interpretation.}