THE BLIND MUSICIAN, An Etude by Vladimir Korolenko

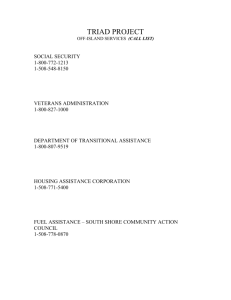

advertisement