I. US Arbitration Law Developments

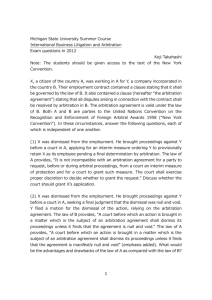

advertisement