09252008

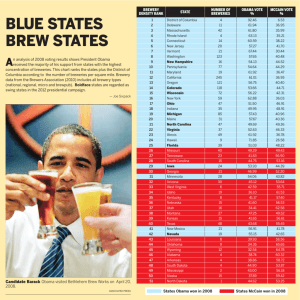

advertisement