10-1

Mallory Ditchfield

N00881902

MNT1- 81395

11/13/14

Case Study #3: Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

1.

IBS is considered to be a functional disorder. What does this mean? How does this relate to Mrs. Clarke’s

history of having a colonoscopy and her physician’s order for a hydrogen breath test and measurements of

anti-tTG? (3 points)

A functional disorder is a certain issue where the body’s normal role or duties are disrupted, but the

disruptions cannot be seen by x-ray, endoscopy, or even blood tests. Since there are no structural

abnormalities in the body that can hold evidence to a disorder, functional-type disorders are diagnosed or

identified by certain types and frequencies of symptoms.1 Functional disorders, like irritable bowel syndrome

(IBS), can cause disturbances and limitations to daily activities. IBS can be defined as an assortment of bowel

disorders distinguished by abdominal distress or pain associated with defecation or a change in bowel habit.2

The colonoscopy listed in her history was ordered to rule out any other types of disorders that might be

the cause of her discomfort. Colonoscopies are necessary to view any damage such as ulcers, inflammation,

or bleeding in the large intestine.2

A hydrogen breath test was ordered by the physician to measure, as it states, the amount of hydrogen

expelled in the breath. This test can help diagnose conditions that have side effects of gastrointestinal

irritation. An elevated amount of hydrogen detected is evidence that the bacteria in the GI tract are being

exposed to unabsorbed food, particularly sugars and carbohydrates. 3 The presence of lactose intolerance can

be detected by the hydrogen breath test. Also, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may be the cause

of elevated hydrogen in the breath. This elevated level is seen in 22%-54% of individuals with IBS. Because

the symptoms of IBS overlap with SIBO, it has been found that many patients with IBS may have underlying

SIBO.4

Anti-tTG (anti-transglutaminase) measurements can be used in the diagnosis of celiac disease.5 The

occurrence of celiac disease has been reported to be four times greater in individuals diagnosed with IBS than

in individuals without IBS.4 Along with that, it has also been reported that approximately 3% of patients with a

“clinical” presentation of IBS were subsequently diagnosed with celiac disease. 6

2.

What are the ACG and the Rome III criteria? Using the information from Mrs. Clarke’s history and physical,

determine how Dr. Cryan made her diagnosis of IBS-D. (2 point)

The American College of Gastroenterology, or ACG, advances in gastroenterology and strives to improve

patient care. There are more than 12,000 GI professionals worldwide that represent the ACG. These expert

members develop new guidelines on gastrointestinal and liver diseases. They base their findings and

guidelines strictly off of evidence-based research and medicine.7

The Rome criteria is a system developed to classify the functional gastrointestinal disorders. 8 Diagnosis of

IBS is based on international consensus criteria, or Rome criteria, and diagnostic algorithms that help separate

other medical or surgical disorders that have similar symptoms. Based on the Rome criteria, abdominal

discomfort or painful symptoms must occur for at least three days each month for the past three months.

Also, the patient must be experiencing at least two of these three indicators: discomfort relieved by

defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and onset associated with a change in form

of stool.4

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a

license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use.

10-2

In order to properly diagnose the patient with irritable bowel syndrome, the physician must refer back to

the ACG and Rome III guidelines. Once the patient meets specified criteria, the physician can be fully

confident with his/her verdict.

Mrs. Clarke stated in her onset of disease history that she has been experiencing diarrhea and

constipation for many years, with ongoing abdominal pain almost every day. This meets the Rome III criteria

of length and frequency of pain and discomfort. She has also stated that she has been experiencing more

bouts of diarrhea in recent months and it is constantly becoming more frequent- stating several episodes per

day. These symptoms all meet the Rome III criteria for IBS-D (diarrhea predominant.) Other factors that lead

to this diagnosis could be her colonoscopy results. Her results came back negative for active disease, thus

pointing to a functional disorder such as IBS.

3.

Discuss the primary factors that may be involved in IBS etiology. You must include in your discussion the

possible roles of genetics, infection, and serotonin. (3 points)

Since IBS is a functional disorder that is based on a variety of symptoms, the etiology will vary. Although

diet, psychological factors, infection, and environmental exposures may cause IBS symptoms, there is no one

answer to the problem. The specific cause of IBS is still unknown. Proposed etiological factors may be studied

in the framework of what is already known about the normal physiology of the gastrointestinal tract.9

In certain cases, an increased sensitivity to specific foods may activate IBS symptoms. There are

numerous reports of food-induced aggravation of IBS with an improvement after elimination of those foods in

the diet.6

IBS has been shown to cluster in families and affect several generations. Genetics may play a role in IBS in

relation to having a strong family history of an allergy or hypersensitivity to certain foods. These factors may

promote or agitate the symptoms.4 Relatives of an individual with IBS are two to three times as likely to have

IBS (both genders affected.)10 This data does not take into consideration that a family as a whole may be

exposed to the same environmental exposures that can cause IBS such as poor nutrition, abuse, or even stress

in the household.

Some evidence suggests that an infection may cause the initial gastrointestinal disturbance and that

tissue sensitization persists after the infection dissipates.11 Post-infectious IBS typically appears abruptly after

gastroenteritis and is essentially managed with the same approach as other forms of IBS.

IBS is commonly described as a “brain-gut disorder” because of the association with serotonin. The

enteric nervous system found in the gut is very similar to the brain. This system sends and receives impulses,

records experiences, and responds to emotions. The nerve cells in the gut are influenced by the same

neurotransmitters found in the brain. The neurotransmitter serotonin can also be found in the gut. If

serotonin is over stimulated, the automatic motion of peristalsis begins.12 This activity can cause diarrhea,

constipation, and discomfort. The mediators of gastrointestinal responses may be abnormal secretion of

peptide hormones or signaling agents such as neurotransmitters secreted in response to the hormones. 4

Leading a stressful life can be a main factor when diagnosing IBS. Also, antidepressant medications like

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) increase serotonin levels, promoting the same issues.12

4.

Mrs. Clarke’s physician prescribed two medications for her IBS. What are they and what is the proposed

mechanism of each? She discusses the potential use of Lotronex if these medications do not help. What is this

medication and what is its mechanism? Identify any potential drug–nutrient interactions for these

medications. (3 points)

The physician has prescribed the medication Elavil (25mg/day) which is a tricyclic antidepressant. Since

Mrs. Clarke meets the criteria of diarrhea-predominant IBS, a low dose of a trycyclic antidepressant can

decrease her symptoms. This type of antidepressant will not promote diarrhea unlike other types such as

SSRI’s mentioned in the previous question.13 Tricyclic antidepressants (in low doses) have also been shown to

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a

license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use.

10-3

reduce discomfort in some cases.4 Low doses of antidepressants are known to block signals of pain to the

brain. This type of antidepressant can, however, can cause dry mouth, a sour or metallic taste, and even

blurred vision.13

Mrs. Clarke was also order the supplementation Metamucil (1 tbsp, 2x/day). Metamucil is a fiber

supplement that can be used to help relieve some symptoms of IBS. Metamucil can help increase the bulk in

stool when ingested in the correct dosage.4

The physicians at the American College for Gastroenterology found that Lotronex can be successful for

treatment of all symptoms related to IBS-D, including abdominal pain, discomfort, urgency, and diarrhea itself.

These results, though, were only found to be significant in female patients. Lotronex works to block

serotonin's effect on the digestive system. Lotronex is able to slow down the colon and reduces the frequency

of bowel movements. Unfortunately, there is a high risk of side effects that may cause serious complications

while taking this medication. Due to these severe risks, this medication is strictly approved for women with

severe IBS-D who have not responded to other treatments. 13

5.

6.

For each of the following foods, outline the possible effect on IBS symptoms. (2 point)

a.

lactose: A simple carbohydrate that causes frequent gas and/or painful bloating. The existence of lactose

indigestion does not automatically mean that it is a cause of IBS, but there is a possibility that the

intolerance can coexist with IBS.9

b.

fructose: A simple carbohydrates that causes gas and bloating.9

c.

sugar alcohols: May cause or worsen diarrhea in patients with IBS or IBS-D.2

d.

high-fat foods: Can cause discomfort, diarrhea, and abdominal cramping.2

What is FODMAP? What does the current literature tell us about this intervention? (2 point)

FODMAP is an acronym that stands for fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharide’s and polyols. These

foods are not well digested and contribute to fermentation which leads to the abdominal discomfort

associated with IBS. A diet low in these saccharides and sugar alcohols has been shown to reduce

gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS.

This diet limits foods that contain fructose, lactose, fructo- and galactooloigosaccharides, and sugar

alcohols. Food sources of FODMAPs are certain fruits such as stone fruits, fruits with high sugar content, dried

fruit, fruit juice, fruit pastes, and fructose as an added sweetener. Honey, coconut, fortified wines, certain

vegetables (onion, leek, asparagus, cabbage), legumes, wheat, and artificial sweeteners are also sources of

FODMAPs.4,9

7.

Define the terms prebiotic and probiotic. What does the current research indicate regarding their use for

treatment of IBS? (2 point)

Foods with fiber, resistant starches, and oligosaccharides may serve as prebiotic foods, which favor the

maintenance of healthy microflora and resistance to pathogenic infections. Probiotics and prebiotics will

increase the amount of short-chained fatty acids produced. In recent studies, short-chain fatty acids have

shown positive results in the absorption of water and electrolytes, thus, reducing the occurrence of diarrhea.

Other research has been conducted illustrating the improvement of mucosal defense in the GI tract when

supplementing with probiotics, along with reducing the growth of other harmful bacteria.

Potential benefits of prebiotics may be shadowed by poor absorption. Some probiotic supplements may

offer benefits in IBS. In larger studies, probiotics have demonstrated improvement for the symptoms of

bloating and gas production. Adding probiotic foods/supplements may be beneficial within the general

nutrition therapy plan, but not as a substitution to conventional medicine. 9 Unfortunately, current results of

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a

license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use.

10-4

initial studies on the use of prebiotic and probiotic supplements with IBS have been mixed; more studies are

needed.

8.

Assess Mrs. Clarke’s weight and BMI. What is her desirable weight? (3 points)

Current Weight: 191 lbs./86.6 kg

Height: 5’5”/1.65 m

BMI9: kg/m2

[86.6/(1.65)2]= 31.8

%IBW11: (current weight/ideal weight) X 100

(191/132) X 100= 144.7%

Mrs. Clarke’s current weight is 191 lbs. Based on the BMI calculation of 31.8, she is considered obese. Obesity

in adults is often defined as having a body mass index of 30 or higher.9 Mrs. Clarke’s percent ideal body

weight (%IBW) has calculated to 144.7%. To assess desirable weight, the individual’s current weight is

compared with an ideal weight calculated from a BMI table. In adults, the midpoint for a healthy BMI is

approximately 22; the weight found at this range is used. For a woman of her height, a BMI of 22 yields

roughly 132 lbs. Her %IBW of 144.7% places her at an increased nutritional risk since she is almost 50% over

her desirable weight.11

9.

Identify any abnormal laboratory values measured at this clinic visit and explain their significance for the

patient with IBS. (3 points)

Upon reviewing Mrs. Clarke’s lab values, I found some test results with slight elevation: glucose is 5 mg

over the suggested range; cholesterol is 2 mg over the suggested range; A1C test showing a 0.9% elevation

based on the normal range. The greatest abnormal lab value it her triglyceride levels. For an adult female, the

suggested range is between 35 and 135 mg/dL. Mrs. Clarke’s triglyceride values resulted with 171 mg/dL.

When assessing current evidence-based research, it is concluded that these lab values do not have any

high significance to an IBS patient. What her lab values do show, however, is her obesity level. Her glucose is

slightly elevated, along with her A1C test placing at high risk for prediabetes. 11 Her obesity is a reflection of

her eating habits, and this is displayed in these elevated lab results.

10. List Mrs. Clarke’s other medications and identify the rationale for each prescription. Are there any drug–

nutrient interactions you should discuss with Mrs. Clarke? (3 points)

Omeprazole (50mg/2xday): Prilosec: Proton pump inhibitor (PPI). PPI’s block the H+, K+-ATPase enzyme

which is a factor in HCL production.9 Mrs. Clarke is prescribed this medicine to control her gastroesophageal

reflux disease (GERD). Approximately 40% of IBS patients have GERD symptoms, therefore PPI therapy is

familiar in IBS patients.14 Long term use for medications for GERD may impair calcium absorption and iron and

B12 status.9 In certain clinical trials, omeprazole may have been a contributor to decreased levels of

magnesium and sodium. Omeprazole/Prilosec should not be taken at the same time as other medications.15

Levothyroxine (25mg): Mrs. Clarke was prescribed this medication due to her hypothyroidism. This is a

condition where the thyroid gland does not produce enough thyroid hormone. Levothyroxine influences

growth and maturation of tissues, is involved in normal growth and metabolism and development, along with

producing stable levels of T3 and T4. There is a decreased absorption rate with iron, calcium, and magnesium

when taking this medication. Decreased absorption is also reported with high-fiber foods.9

Lomotil (prn): Patients with IBS-D might benefit from an antidiarrheal agent such as Lomotil. These types

of medications aid by decreasing motility and increasing consistency of the stool. 9 There is a moderate

interaction with Lomotil and alcohol consumption. The combination results in dizziness, drowsiness, and

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a

license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use.

10-5

decreased mental alertness. Since Mrs. Clarke consumes alcohol three to four times a week, this

drug/nutrient interaction will need to be discussed. 16

11. Determine Mrs. Clarke’s energy and protein requirements. Be sure to explain what standards you used to

make this estimation. (3 points)

The DRI committee has formatted an isolated set of equations for calculating energy requirements in

individuals that are overweight or obese.

Total Energy Expenditure (TEE) for obese females aged 19 years and older 9:

TEE= 448 – 7.95 X age + PA X (11.4 X weight + 619 X height)

TEE= 448 – 7.95 X 42 + 1.16 X (11.4 X 86.6 + 619 X 1.65)= 2,280.65

RDA for Protein9: 0.8g per kg body weight

0.8 X 86.6= 69.28g

Since Mrs. Clarke leads a sedentary life with little exercise, her need for protein is reduced.

12. Assess Mrs. Clarke’s recent diet history. How does this compare to her estimated energy and protein needs?

Identify foods that may potentially aggravate her IBS symptoms. (3 points)

In order to estimate Mrs. Clarke’s usual intake of calories, I used the USDA’s Choose My Plate food

tracker.17 Based on her reported intake for the past several months, she consumes approximately 2,000

calories each day. This is just below her TEE that was calculated in the previous question. Her diet is high in

refined grains and empty calories. Unfortunately, her diet is also exceedingly high in common IBS food

triggers. Her RDA for protein calculated to be ~70g per day. Based on her usual daily intake, she is meeting

her requirements with roughly 75g.

Mrs. Clarke’s intake of 2-3 cups of coffee for breakfast and diet Pepsi at lunch may be exacerbate her

gastrointestinal symptoms. Caffeine has been shown to have negative effects in people suffering with IBS.

Also, her consumption of alcohol could be creating the same painful contributions. 11

Other foods in her diet that are familiar triggers for IBS: peaches and cherries (stone fruits), dried fruit,

wheat-based breakfast cereal, asparagus, kidney beans, lentils, wheat pasta, wheat/white bread, wheat-based

cookies, cakes and crackers, and artificial sweeteners.

13. Prioritize two nutrition problems and complete the PES statement for each. (5 points)

Altered GI function related to suspected IBS-D as evidenced by recurrent abdominal pain/discomfort for

at least 6 months, symptoms experienced on at least 3 days of at least 3 months, alternating constipation

and diarrhea, and predominant diarrhea with several episodes per day.

Poor nutrition choices and intake related to lack of knowledge as evidenced by BMI in obesity range, usual

intake from dietary recall, and frequent ingestion of IBS-triggering foods.

14. The RD that counsels Mrs. Clarke discusses the use of an elimination diet. How may this be used to treat Mrs.

Clarke’s IBS? (2 point)

Given that Mrs. Clarke is consuming many of the common IBS generating foods, an elimination diet is

vital in pin-pointing those certain foods. A traditional elimination or exclusion diet removes all possible foods

related to the patient’s symptoms. Once the foods are removed, they are slowly added back within a certain

time period. Once these foods are being eaten again, if the patient experiences no added symptoms these

foods can be categorized as non-IBS triggering foods and are acceptable in the diet. 9

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a

license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use.

10-6

15. The RD discusses the use of the FODMAP assessment to identify potential trigger foods. Describe the use of

this approach for Mrs. Clarke. How might a food diary help her determine which foods she should avoid? (2

point)

Since FODMAP foods are not well digested and contribute to fermentation, abdominal distress and pain

may arise. A FODMAP assessment to identify potential trigger foods in Mrs. Clarke’s diet may help alleviate

certain symptoms. Fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides, and polyols consumed on a regular basis

are potential triggers for IBS and they are recurrent in Mrs. Clarke’s diet. Fruits with high sugar content and

stone fruits, dried fruit, wheat-based breakfast cereal, asparagus, kidney beans, lentils, wheat pasta,

wheat/white bread, wheat-based cookies, cakes and crackers, and artificial sweeteners are all common in her

diet and are all FODMAP foods.

Keeping a food diary and writing entries each day can help determine what foods, habits, or

environmental factors are causing her symptoms. Logging foods eaten with symptom levels after each meal is

necessary to the food diary. It might also be helpful to add energy levels and moods throughout the day.

Once a certain food is eliminated, it is important to write down how she is feeling immediately after, and

possibly the day after. After a week or so, if she is still experiencing no signs or symptoms after that food was

eliminated, the food can be labeled in the diary as a non-triggering food.

16. Should the RD recommend a probiotic supplement? If so, what standards might the RD use to make this

recommendation? (2 point)

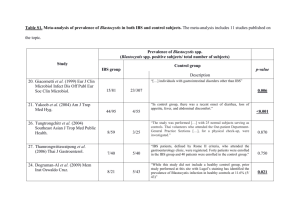

Probiotics, when compared against a placebo, show an improvement in IBS symptoms. These studies

illustrate a decrease in abdominal distress, bloating, and gas. The two strains, Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus, have both been studied for their impending use in prevention and management of IBS. 18 One

study found that probiotic treatment significantly improved IBS symptoms along with an enhanced quality of

life. The researchers mainly used the bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacteria infantis. The

results showed that these improvements and positive effects began to occur after taking the probiotics

consistently over a four week period.13

Based on the patient and their specific type of gastrointestinal disorder, probiotics can be of some

assistance to discomfort in the abdominal region. Adding probiotics may be beneficial within the overall

nutrition plan. It is necessary, first, to ensure the patient does not have an intolerance to lactose. Since the

presence of lactose indigestion causes similar discomfort, it is important to note that lactose intolerance is not

the cause of IBS, but the two can co-exist.9

17. Mrs. Clarke is interested in trying other types of treatment for IBS including acupuncture, herbal supplements,

and hypnotherapy. What would you tell her about the use of each of these in IBS? What is the role of the RD

in discussing complementary and alternative therapies? (2 point)

Since stress has been shown to complicate or increase symptoms of IBS, behavioral therapy might be a

suitable alternate route when considering treatment. Behavioral therapy includes a long list of different

methods and practices to better understand how to cope with stress, pain, and uncomfortable situations.

These strategies can help improve symptoms in patients suffering with IBS. Relaxation therapy, hypnotherapy,

cognitive behavioral therapy, and psychotherapy are all suggested options when considering this form of

management. It might be helpful to the client to suggest other forms of complementary or alternative

therapies. These may be found in meditation, exercise, having an ample amount of sleep, or even becoming

involved in enjoyable activities.13

Other alternative therapies, such as acupuncture and herbal supplements, have not yet been scientifically

proven to show any effectiveness in the treatment for IBS. Some smaller-scale studies have been done in

relation to acupuncture and IBS, resulting in a positive effect on quality of life. Regardless of this information,

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a

license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use.

10-7

there is still no medical or science-based evidence that would qualify this as a successful alternative therapy.15

I would not disapprove of the clients use of acupuncture, but I would reiterate the lack of evidence-based

research behind it.

Herbal remedies and supplementation are very popular among people suffering with IBS. The majority of

research regarding herbal use has taken place in China. Unfortunately, the studies done are of meager quality

and show very limited and weak evidence. However, peppermint oil (an antispasmodic9) was studied and has

proven useful in relieving some symptoms such as abdominal discomfort caused by bloating and gas. 14 If the

client showed interest in herbal remedies, I would explain the current research for that specific herb and base

my suggestions off of the studies. If the client were to ask which herbal supplementation I would suggest,

based on the evidence, I would most likely recommend the supplementation of peppermint oil or tea.

The role of the RD when discussing the use of these alternative choices is, simply, to counsel and make

recommendations to the client. It is important to be non-judgmental in this type of setting and to back up any

suggestions with evidence. If a client spoke of interest in complementary and alternative medicines, it is

important to discuss each alternate choice individually. Coaching is needed to help educate the client on the

reason for use or non-use, dosage information, and any safety concerns or interactions. Registered Dieticians

should be in the know and fairly knowledgeable in regards to the more common types of complementary and

alternative medicines/therapies in order to fully advise the client/patient.

18. Write an ADIME note for your initial nutrition assessment with your plans for education and follow-up. (5

points)

Assessment:

42 year old female, gastrointestinal discomfort with constipation and diarrhea, history of hypothyroidism,

GERD, and obesity. Height 5’5”, weight 191 lbs., BMI 31.8, obesity I. Patient is a divorced kindergarten teacher

who lives with her two children and mother. She eats three meals a day with snacks (cookies, cakes, dried

fruit and nuts), and visits restaurants/take-out once per week. Drinks diet soda often and alcohol three to

four times a week. Meals usually consist of a meat source (mostly chicken), a starch, and vegetables with a

dinner roll. Low activity level.

Diagnosis:

Altered GI function related to suspected IBS-D as evidenced by recurrent abdominal pain/discomfort for at

least 6 months, symptoms experienced on at least 3 days of at least 3 months, alternating constipation and

diarrhea, and predominant diarrhea with several episodes per day.

Also, many undesirable food choices and intake related to lack of knowledge as evidenced by nutrition history,

BMI in obesity range, usual intake from dietary recall, and frequent ingestion of IBS-triggering foods.

Intervention:

Provided basic education on IBS symptoms, triggers, eating smaller meals, and common nutrition in relation to

her diet high in refined grains, sugar, alcohol, and sodium. Introduced the use of elimination/exclusion diet

with a food diary. Patient will use information given in our sessions to adjust her diet and also begin to

eliminate the triggering foods discussed. Will return in three weeks with food diary to assess progress.

Monitoring and Evaluating:

Will monitor patient’s weight, intake, and clinical symptoms in response to elimination diet. Lab values may

also be monitored if necessary. Food diary will continue until the patient can gain a better understanding of

what triggers her symptoms (also will keep on hand for records). Will keep up with education and assistance

for any new questions or problems with the patient that may arise in the future.

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a

license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use.

10-8

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Functional GI Disorders. Available at:

http://www.iffgd.org/site/gi-disorders/functional-gi-disorders/. Accessed on: November 10, 2014.

International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. About Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Available at: http://www.aboutibs.org/. Accessed on November 10, 2014.

Medicine Net. Hydrogen Breath Test. Available at:

http://www.medicinenet.com/hydrogen_breath_test/article.htm. Accessed on: November 10, 2014.

Krause’s Food and Nutrition Therapy, 13th Edition. Mahan K, Escott-Stump S. Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

PubMed. Role of anti-transglutaminase (anti-tTG), anti-gliadin, and anti-endomysium serum antibodies in

diagnosing celiac disease: a comparison of four different commercial kits for anti-tTG determination.

Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11344524. Accessed on: November 10, 2014.

National Center for Biotechnology Information PMC. Between Celiac Disease and Irritable Bowel

Syndrome: The “No Man’s Land” of Gluten Sensitivity. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3480312/. Accessed on: November 11, 2014.

American College of Gastroenterology. Membership and Clinical Guidelines. Available at: http://gi.org/.

Accessed on: November 12, 2014.

Rome Foundation. Rome III Disorders and Criteria. Available at: http://www.romecriteria.org/criteria/.

Accessed on: November 11, 2014.

Nutrition Therapy and Pathophysiology Nelms M, Sucher K, Long S. Thomson/Wadsworth, Australia, Third

Edition, 2010- 2011.

National Center for Biotechnology Information PMC. The Role of Genetics in IBS. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3056499/. Accessed on: November 10, 2014.

Rolfes SR, Pinna K, Whitney E. Understanding Normal and Clinical Nutrition, 8 th ed. Cengage Learning;

2011.

PubMed. Enteric nervous system, serotonin, and the irritable bowel syndrome. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17031157. Accessed on: November 10, 2014.

WebMD. Treating Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Diarrhea. Available at:

http://www.webmd.com/ibs/treating-diarrhea?page=2. Accessed on: November 10, 2014.

Medscape. Proton Pump Inhibitors, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth.

Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/723772. Accessed on: November 12, 2014.

Rx List. Prilosec. Available at: http://www.rxlist.com/prilosec-drug/side-effects-interactions.htm. Accessed

on: November 12, 2014.

Drugs.com. Lomotil (atropine / diphenoxylate) and Alcohol / Food Interactions. Available at:

http://www.drugs.com/food-interactions/atropine-diphenoxylate,lomotil.html. Accessed on: November

12, 2014.

Choose My Plate. Super Tracker. Available at: https://www.supertracker.usda.gov/foodtracker.aspx.

Accessed on: November 12, 2014.

NIH, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Irritable Bowel Syndrome

and Complementary Health Practices. Available at:

http://nccam.nih.gov/health/digestive/IrritableBowelSyndrome.htm. Accessed on: November 11, 2014.

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part, except for use as permitted in a

license distributed with a certain product or service or otherwise on a password-protected website for classroom use.