Kallie Haas - DifferentiatedInstruction

advertisement

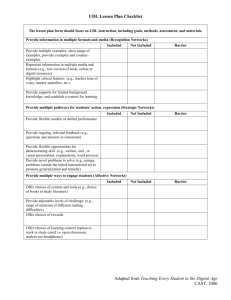

Kallie Haas ED 878.502 Differentiated Instruction Strategy Wiki American education in the 21st century reflects the vast and diverse students that sit within the classrooms across the United States. Educational pedagogy has evolved over time. One-room schools have been replaced with full-inclusion classrooms where students with disabilities, students learning English as their second language, and gifted students sit side-by-side. These students tap into wireless internet from their laptops, their teachers connect them to classrooms from around the world and the demands placed on students continue to rise. America was founded on the principles of freedom of religion, speech and with the idea that “all men are created equal.” Equality and equity are cornerstones for public education today. Traditional methods of instruction are being replaced by Universal Design for Learning (UDL) lessons that promote the strengths students bring to the classroom, as well as foster student self-reflection. UDL is a lesson planning format that naturally provides differentiation of instruction, assessment and for the classroom environment. UDL is becoming the standard for educators to use with students with disabilities or English language needs, as well as gifted and talented. “Inflexible, one-size-fits-all” (CAST, 2008) lesson plans are no longer acceptable, and deny students equitable education. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is the newest wave of educational practice that acknowledges that there are diverse learners in every classroom, and actively works to promote differentiation, which in turn provides educational equity. The UDL framework evolved from universally designed architecture and products in the 1980s that provided greater access to public environments, such as libraries, restaurants, and movie theaters. These accommodations also benefited the greater society: many mothers use the handicap stalls when caring for young children, or utilize the automatic opening doors when their hands are full and cannot pull the door open (MessingerWillman & Marino, 2010, p. 8). The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) is the leading organization to spread awareness and training of the UDL principles and practices. Their work is cited in all the research done on UDL. To implement Universal Design for Learning, an educator must understand the students within the classroom: the individual and group strengths, areas of deficit, language needs, assistive technology needs, hearing and visual needs, and more. CAST recommends breaking a lesson or unit into three main categories. The educator will: 1) provide multiple means of representation 2) provide multiple means for action and expression 3) provide multiple means for engagement. (CAST 2008) Once an educator analyzes his/her students, that teacher can use any of the graphic organizers/planners available from CAST. The graphic organizers assist the short-term and long-term planning, as well as provide assistance for formative and summative assessments. These recommendations require an educator to frame his/her lessons around the students, instead of making the students fit the curriculum. The teacher can utilize scaffolding strategies within this framework. UDL is the combination of what the best educators have been doing for years and what brain research shows is necessary for students to learn: making instructional decisions that have the students’ best interest in mind. Universal Design for Learning can and is being implemented in collaboration with Response to Intervention (RtI) practices. Since 2004, RtI is a “proactive approach to intervening services prior to special education services” for students who need more support than the general education curriculum offers (Basham, Israel, Graden, Roth & Winston, 2010). RtI is a tiered support framework that prevents overidentification for special education services. Basham, et al (2010) found that Universal Design for Learning and Response to Intervention “share common purposes and features that support” special education law (p. 244). By framing lessons around the students’ needs, the educator is adapting the environment, the instruction and assessment, which provides more accessibility to all students, not just those with special education services. There are interventions naturally occurring within the classroom. These interventions support RtI. Both RtI and UDL are “data based decision making” tools and both should utilize technology to support student learning (Basham, et al, 2010, p. 244) across content areas. Not only is UDL being implemented in elementary and secondary schools, but it is reaching the post-secondary education levels. Greater teacher preparation programs are instructing using the UDL principles in order to model appropriate methods to preservice teachers. Jiménez, Graf and Rose (2007) argue that is should be the responsibility of the universities to help enact this pedagogical change in the American education system (p.50) if we are to expect other educators to adapt to this change. Professors Thom Morra and Dr. Jim Reynolds argue that there needs to be an increase of universally designed technology-enhanced courses. Morra and Reynolds believe an online or hybridonline course help make education accessible to greater numbers of people, but just because it is an online class, does not mean it match the needs of all students. The authors provide many differentiated strategies for technology based classes, such as giving the students “choice between multiple ways to complete assessments” (p. 46) and providing “flexibility in how they will present the final product” (p. 47). The U.S. Department of Education supports technology based classes to promote accessibility to underserved children and adults, particularly minority, low-income and disabled. They recommend the following applications of UDL for courses: “language translators on the web for English Language Learners” and increasing the number of online classes available for adult learners. By increasing technology and UDL principles to increase educational opportunities, the Department of Education hypothesizes the country can improve its economic prosperity (http://www.ed.gov/ technology/draft-netp2010/who-needs-to-learn). Messinger-Willman and Marino (2010) propose relying on both assistive technology (AT) and Universal Design for Learning technologies to provide inclusive practices for all students. Simply by expanding the use of word processors available for written expression, the educator is supporting AT for students with special education services/accommodations, as well as supporting other students who may struggle with organization or spelling or grammar, thus providing universally accessible lessons. Stobel, Arthanat, Bauer and Flagg (2007) cite research that demonstrates increased language fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension for ELLs when the television closed captioning is turned on. One change in the learning environment, closed captioning, not only provides access to deaf students, but ELLs, students with learning disabilities and students considered “at-risk” (p. 84). Universal Design for Learning requires training and hard work for educators unfamiliar with the framework. One cannot be expected to create master UDL lessons immediately. It will take time to adapt to this framework. However, shifting the focus away from “the problem is with the students” to “the problem is with the curriculum,” the teacher will be creating the right mindset to provide equitable and accessible education to every single learner in the classroom. The UDL framework provides multiple means for differentiation, technology supports, and creativity from both the student and teacher. References Basham, J. D., Israel, M., Graden, J., Poth, R., & Winston, M. (2010). A comprehensive approach to RtI: Embedding universal design for learning and technology. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 33, 243-255. Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). (2009). Universal design for learning guidelines version 1.0. About CAST. Wakefield, MA: Author 4/29/2009 (revised). Jiménez, T. C., Graf, V. L., & Rose, E. (2007). Gaining access to general education: The promise of universal design for learning. Issues in Teacher Education, 16, 41-54. Messinger-Willman, J., & Marino, M. T. (2010). Universal design for learning and assistive technology: Leadership considerations for promoting inclusive education in today’s secondary schools. NASSP Bulletin, 94, 5-16. doi:10.1177/0192636510371977 Strobel, W., Arthanat, S., Bauer, S., & Flagg, J. (2007). Universal design for learning: Critical need areas of people with learning disabilities. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits, 4(1), 81-98. U.S. Department of Education. Who needs to learn. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/ technology/draft-netp-2010/who-needs-to-learn