Public Sector Governance and the Finance Sector

advertisement

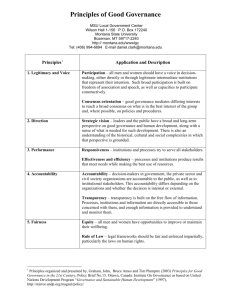

Public Sector Governance and the Finance Sector Dr Jeffrey Carmichael Chairman, Carmichael Consulting Pty Ltd Former Chairman, Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Presentation delivered to: A Regional Seminar on Non-Bank Financial Institutions Development in African Countries December 9-11, 2003, Mauritius Sponsored by the World Bank Public Sector Governance and the Finance Sector 1. Introduction In recent years there has been a growing focus on corporate governance in the finance sector reform programs sponsored by international organizations such as the World Bank and the IMF. I want to shift that focus to the less popular and considerably more sensitive parallel need for international improvements in public sector governance. I believe that, of the two, public sector governance is almost certainly the more critical. The reason for this belief is that: The size of the gains on offer are greater in the public sector, and Improvements in corporate governance are unlikely to occur unless they take place alongside public sector governance reforms. There is a relatively new and creative literature emerging on this topic, mainly out of the World Bank and Brookings Institution. Most of this concentrates on corruption and its impact on economic growth and welfare. This is very important - and I should add – courageous work. However, I want to concentrate just on public sector governance in the finance sector. While this is a narrower focus, it is made more complicated by the fact that there are many legitimate roles for the public sector in the finance sector. Consequently, poor public sector governance has aspects that extend well beyond the effects of corruption. 2. Outline This is a very broad topic and I will just focus on a few key areas: First, I want to define public sector governance and look at where the problem comes from; Second, I want to look briefly at areas in which public sector governance problems arise and the costs that can follow from poor governance; and Third, I want to offer some thoughts on how to go about addressing just a few of the public sector governance problems. 2 3. Definition of Public Sector Governance There is not yet any universally agreed definition of public sector governance. My preferred definition is: “The systems and processes by which a company or government manages its affairs with the objective of maximizing the welfare of and resolving the conflicts of interest among its stakeholders.” In essence, governance is about the way in which a company or Government proposes to reconcile the conflicting interests of its various stakeholders and the structures it puts in place to ensure that these objectives are met; that is, it encompasses both policy and practice. Fundamentally, good governance is about resolving conflicts of interest. At the heart of the conflict problem is agency costs – those conflicts and costs that arise when the principal in any operation or transaction appoints an agent to look after his/her interests. The problem is that: • When I act for myself as a principal, I know exactly whose interests I am pursuing; • Delegation, however, implies a loss of control and the possibility that my agent will pursue his own interests instead of mine; • Solutions to the agency problem that arises in corporate situations focus mainly on inappropriate incentives – that is, how can the principal write a contract with appropriate incentives for the agent to pursue courses of action that coincide with the principal’s best interests. • The public sector agency problem has some of the same elements. But, more important, and often overlooked, is that principal/agent agreements in the public sector often lack clarity – in short, the problem in the public sector is often that the principal fails to specify with sufficient clarity what interests are to be pursued and how the agent is supposed to achieve them. This is a point I will come back to when I look at some solutions. 4. Areas in which Public Sector Governance Problems can arise Before I do that, let me look briefly at areas in which public sector governance problems can arise in the finance sector and why good public sector governance is so critical. The public sector participates in the finance sector of most economies to an extent and in ways that are quite unlike its role in other sectors of the economy. This participation typically includes some or all of the following: As the regulator of financial institutions; 3 As an owner of financial institutions (banks and insurance are common – creates implicit guarantee plus possible access to information and opportunities for corruption); As a market participant (e.g. governments issue debt and trade in it – access to information); As a fiduciary agent (through pension schemes in particular – access to funds for corruption and political purposes); and Through direct intervention in the operations of the market (guarantees, direct support and directed lending). Each of these involves principal/agent problems and conflicts of interest between the public sector, its agents and the public. It is important to identify who the principals and agents are in some of these situations. In many cases there are several levels of principal and agent. For example, in the case of regulation, the ultimate principals are the public, who benefit from good regulation and who suffer when regulation falls short. The public delegate their interests to the government as their agent. The government in turn typically delegates the responsibility for regulation to a regulatory authority. Within the regulatory authority there may be multiple levels of delegation. For example, from a board to senior management and from senior management to staff. That creates four or more levels of principal/agent delegation and therefore multiple levels at which governance issues can arise. Let’s look now at why good governance so important in the public sector context. While the underlying principles are the same as in corporate governance, the problems are more complex, more difficult to resolve, and the costs of poor governance are potentially much greater than those of poor corporate governance. The first level of complexity relates to the difficulty of measuring, and therefore monitoring, the principal/agent problem. Unlike the corporate sector, there is no simple metric such as profitability by which to measure the performance of the public sector. This also applies to measuring the costs of poor governance. For example, how do you measure the opportunity cost, in terms of foregone production and human suffering, of poor advice from a Department of Finance that leads to recession, or of an under-resourced regulatory agency that fails to prevent an impending financial crisis. There is therefore an inherently low level of transparency about the public sector. 4 Second, unlike the situation facing corporate shareholders, there is no ‘market’ for principals who wish to exit their exposures to the public sector. Unlike shareholders, citizens cannot ‘sell’ their vote, other than at election time. Like minority shareholders, they have little leverage, other than at election time, to force the government to alter its behaviour. Third, governments and their bureaucracies possess temporary monopoly power. For example: The department responsible for issuing import licenses, for example, does not do so in competition with other departments; With the exception of the US, financial regulators usually have a monopoly over their particular area; The immigration clerk issuing entry visas or work permits has an unequal bargaining position relative to the applicants. The main effect of this temporary monopoly power is the opportunity it creates for corruption. However, while corruption is arguably the main manifestation of poor public sector governance, it is by no means the only one. The importance of this distinction is more apparent in the finance sector than in other sectors of the economy due to the pervasiveness of the public sector in finance. In looking at the costs, let me start with corruption. There has been some very good work done on measuring corruption and its impact on the economy. The main conclusions of this research are surprisingly robust: Corruption reduces domestic investment Corruption reduces foreign direct investment Corruption reduces economic growth Corruption reduces government revenue, increases the size of government expenditure and tends to bias it away from operations, maintenance and social infrastructure such as health and education, in favor of new equipment and physical infrastructure. Corruption reduces the effectiveness of financial regulation and leaves the system more vulnerable to currency crises. Corruption tends to increase the size of the underground economy. The most striking features of this growing research are the sizes of the estimated impacts of corruption and the extent to which they carry social as well as economic implications. 5 While corruption is a major source of cost, it is by no means the only one that arises in the finance sector from poor public sector governance. Even without the explicit motive of personal gain, government involvement, without adequate rules to govern that involvement, can impose substantial costs on the community. Some of the more important of these are: First - Poorly-designed financial regulation can expose the financial system to crisis and collapse. The biggest impact here comes from poor transparency regulation. Second - Where publicly-owned financial institutions are not subject to the same prudential and conduct regulation as private sector firms, competition can be distorted, innovation can be retarded, and signs of financial distress in the public institutions are likely to be disguised until the problem becomes a crisis. Third - Attempts to reform regulation and governance among private sector financial institutions are likely to fail unless publiclyowned/managed financial institutions are subject to rules of behaviour at least as stringent as those imposed on private firms. Fourth - A lack of transparency in public sector fiduciary relationships can be a source of long-term financial hardship and disappointed expectations. Fifth - Since the attitude of the public sector with respect to its own market conduct conveys an important signal to private sector market participants, the way in which it handles conflicts of interest, privileged information and disclosure will have an important bearing on the integrity of private sector financial markets. Sixth - Government intervention in financial markets carries a significant element of moral hazard. This has been borne out again and again by countries that have stepped into crises with public sector guarantees of deposits and other financial claims. These have a way of escalating the size of the problem as unscrupulous operators take advantage of the guarantees or support to send good money after bad. 5. Addressing Public Sector Governance in the Finance Sector So how do we address the public sector governance problem? I believe there are five main elements to the solution: First there is a need to agree a framework for assessing the appropriate role of the public sector in the financial system; Second, where participation extends beyond the appropriate roles, devise a process for winding back that involvement; 6 Third, establish a set of Public Sector Governance Principles to apply to the legitimate, on-going participation of the public sector in the financial system; and Fourth, where the gap between the ultimate objective and the starting point are too great, identify some practical steps to begin the process. Fifth, we need to provide some practical guidance on how to implement good governance. Given my limited time I want to comment briefly on just a couple of these issues. The first issue I want to comment on is the need for some internationally agreed principles of public sector governance. Important components of such a set of Principles are already contained in the IMF Code of Good Practices on Fiscal, Monetary and Financial Policies. These Principles, however, need to be extended and modified slightly to cover regulation and public sector ownership – particularly in the following areas: Transparency and Accountability of regulators and Publicly-owned enterprises; Independence of Financial Regulatory Agencies; and Anti-Corruption Measures. The first of these is a fairly easy extension of the IMF Code. The second requires Governments to face up to some simple realities. Since many Governments participate in the financial sector as both an owner and a market participant, good governance demands that regulatory agencies have a high degree of independence or autonomy from the Government. It also demands that Government-owned financial institutions be subjected to the same regulatory standards as their private sector competitors. Too many Governments are content to allow their own public sector institutions to enjoy a market advantage from soft regulation – and then look for scapegoats when these institutions fail. The third missing element of the Principles is the need for anti-corruption measures. The existing IMF principles for Monetary and Fiscal policy focus a lot on disclosure and transparency of Government agencies. Corruption thrives on secrecy. Therefore, any measures that improve disclosure and accountability are natural opponents of corruption. So too are measures that that provide regulators with legal protections against capricious removal from office and also against prosecution for doing their jobs in good faith. The other area I want to comment on is the need for practical guidance on implementing principles of good governance. 7 Let me give an illustration of what I mean. I mentioned earlier the need for clarity in directions from principals to agents. A key component of the principal/agent problem is that it involves delegation. How then can we establish an approach to delegation that provides clarity? I recently went through a review session with the Board of the Mauritian FSC in which we developed such an approach for delegations from the Board to Senior Management. The essence of that approach was the following. First, the Board members agreed that as a non-executive Board they could not be hands on with ever issue – Boards cannot micro-manage. Following from that, the Board agreed they needed a process for deciding when to be hands on and when to be hands off. That meant they needed to: Prioritize Board involvement; Give clear directions to Management as to how they were to exercise their delegations where the Board decided to be hands off; and Establish an accountability process to satisfy the Board that their directions were being observed. In order to prioritise Board involvement we started by breaking the agency’s responsibilities down into a series of functions and activities, such as formulating policy, formulating procedures, enforcement, administration, and so on. Some of these could be delegated and some could not. For example, the Board agreed that it could not reasonably delegate responsibility for formulating policy, whereas it could delegate responsibility for the day-to-day administration of the agency. In a sense they created a scale of “hands onness” for these functions and activities. For each of these functions they established an appropriate set of responsibilities for the Board and for Management. For example, the Board may be responsible in a given area for establishing policy, while Management may be responsible for putting the details on the policy and for implementing it. The final stage of the process was to create a formal written delegation document that spelled out clearly the objectives of the function, the roles and responsibilities of the different parties, how Management were to carry out their delegated responsibilities, and finally how Management were to account to the Board for the exercise of their delegated responsibilities. By working through each area and function of the agency, the Board would then establish a comprehensive delegation framework. I think I can say, without casting dispersions on my fellow regulators, there would be very few regulatory agencies in the world that could claim to have such a comprehensive framework. 8 Closing Comments By way of closing, let me say that strengthening public sector governance is possibly one of the greatest challenges we face internationally. Without good public sector governance, financial markets are unlikely to operate efficiently or effectively, corruption is likely to retard economic growth and welfare, and efforts to reform private sector performance, through regulatory reform, corporate governance reform and anti-corruption measures, are largely doomed to failure. The stakes are high and there is a need to put much greater efforts into public sector governance in coming years. This is an issue for both emerging and developed markets. But the urgency for emerging markets is much greater because of the risk otherwise of being left behind in the global world without the capacity to benefit fully from the developments taking place around you and with an ever increasing vulnerability to crisis. 9