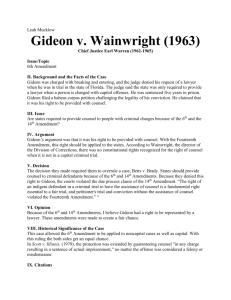

Rothgery v. Gillespie County, 128 S. Ct. 2578

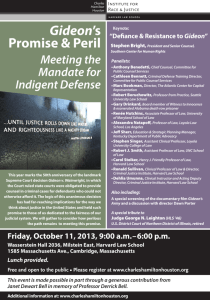

advertisement