Lecture Notes - Durham University Community

advertisement

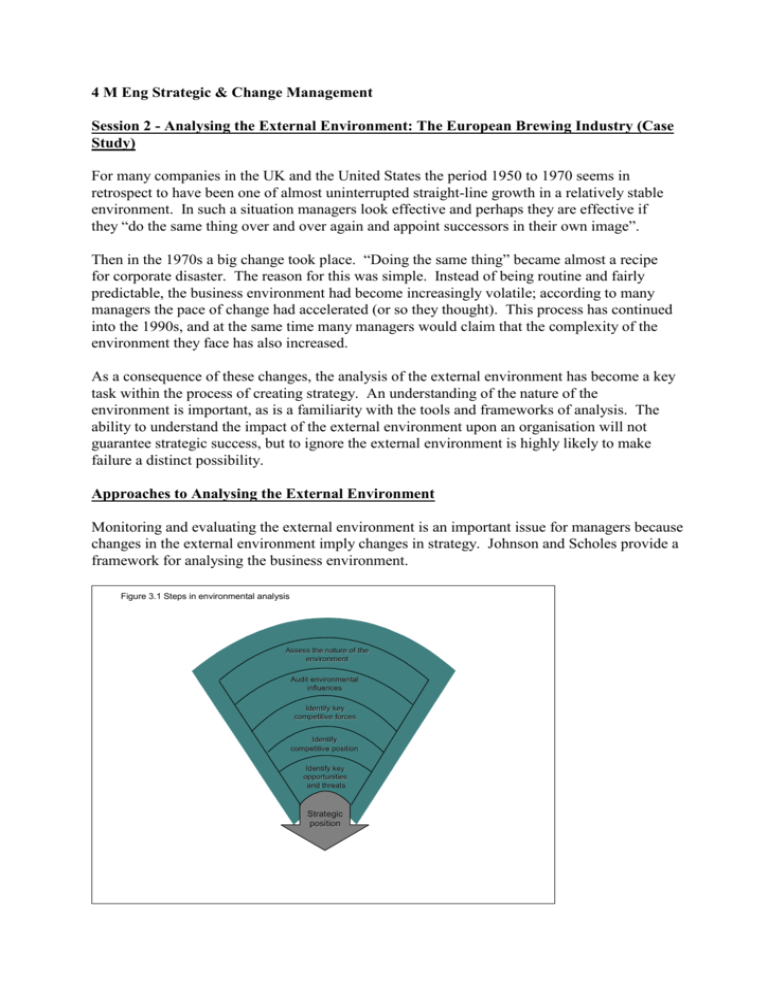

4 M Eng Strategic & Change Management Session 2 - Analysing the External Environment: The European Brewing Industry (Case Study) For many companies in the UK and the United States the period 1950 to 1970 seems in retrospect to have been one of almost uninterrupted straight-line growth in a relatively stable environment. In such a situation managers look effective and perhaps they are effective if they “do the same thing over and over again and appoint successors in their own image”. Then in the 1970s a big change took place. “Doing the same thing” became almost a recipe for corporate disaster. The reason for this was simple. Instead of being routine and fairly predictable, the business environment had become increasingly volatile; according to many managers the pace of change had accelerated (or so they thought). This process has continued into the 1990s, and at the same time many managers would claim that the complexity of the environment they face has also increased. As a consequence of these changes, the analysis of the external environment has become a key task within the process of creating strategy. An understanding of the nature of the environment is important, as is a familiarity with the tools and frameworks of analysis. The ability to understand the impact of the external environment upon an organisation will not guarantee strategic success, but to ignore the external environment is highly likely to make failure a distinct possibility. Approaches to Analysing the External Environment Monitoring and evaluating the external environment is an important issue for managers because changes in the external environment imply changes in strategy. Johnson and Scholes provide a framework for analysing the business environment. Figure 3.1 Steps in environmental analysis Assess the nature of the environment Audit environmental influences Identify key competitive forces Identify competitive position Identify key opportunities and threats Strategic Strategic position position The framework is a general one so you must remember: To take a holistic view; To adapt what you read to the circumstances; That the most difficult aspect of environment analysis is often that of deciding exactly which factors are the most important; That new factors and new priorities will arise as circumstances change. There are two further points about environmental analysis that are worth noting: Otherwise ably-managed companies are frequently taken by surprise by events what may seem to the observer to have been quite predictable; Businessmen are prone to describe their failures as bad luck and their successes as good management. Both points illustrate a key factor in environmental analysis - it isn't entirely objective. Information is coloured by the perceptions, expectations and prejudices of the manager. If we view environmental analysis as a scientific experiment, then the analyst (manager) is part of the experiment. Results in terms of forecasts are as much the product of expectations, prejudices, assumptions and typology as they are of “objective” circumstances. What are the principal trends in the European brewing industry? The wide range of potential influences on an organisation and their interaction, make the job of assessing the general environment particularly difficult. In addition, each organisation is affected in different ways by changes in the environment. Factors that have a significant impact upon one organisation will have little effect on another. For example, the recent changes in the funding of students in the UK is of particular concern to universities like Durham, but will have only a marginal impact on a retailer like Marks & Spencer. PEST (Political; Economic; Social; Technological) analysis provides a systematic technique for analysing the business environment. It enables the manager to: Summarise the most important influences of the business environment; Evaluate the potential impact of these influences on the organisation. Using PEST analysis can help to highlight the biggest influences on the strategy of the organisation, both currently and in the future. These influences can be both positive and negative. In addition, influences often cross the divide between the four headings; the important point is that they appear somewhere in the analysis. The key is to identify and concentrate upon those factors/trends likely to have the biggest impact upon the future of the organisation. Johnson and Scholes outline some of the most likely factors. Figure 3.3 A PEST analysis of environmental influences 1 . W h at en viro n m en tal facto rs are affectin g th e o p p o sitio n ? 2 . W h ich o f th ese are th e m o st im p o rtan t at th e p resen t tim e? In th e n ext few years? P o litical/leg al M onopolies legislation E nvironm ental protection law s T axation policy F oreign trade regulations E m ploym ent law G overnm ent stability E co n o m ic facto rs B usiness cycles G N P trends Interest rates M oney supply Inflation U nem ploym ent D isposable incom e E nergy availability and cost S o cio cu ltu ral facto rs P opulation dem ographics Incom e distribution S ocial m obility Lifestyle changes A ttitudes to w ork and leisure C onsum erism Levels of education T ech n o lo g ical G overnm ent spending on research G overnm ent and industry focus of technical effort N ew discoveries/ developm ent S peed of technology transfer R ates of obsolescence Applying PEST analysis to the European Brewing Industry case study reveals a number of potentially significant factors/trends. A PEST ANALYSIS OF THE EUROPEAN BREWING INDUSTRY POLITICAL Harmonisation of duty rates across European Union member states Competition legislation - e.g. 1989 Monopolies and Mergers Commission report in the UK Local production laws - like Reinheitsgebot in Germany Restrictions on containers - like the use of cans in Denmark ECONOMIC Different patterns of industry concentration across countries Growing trend towards cross-border mergers and acquisitions Low growth in consumption of beers SOCIAL Growing concerns about health issues and drink-driving Increasing acceptance of low alcohol drinks Importance of supermarkets in distribution and growth of own-label products Increasing acceptance of pan European brands TECHNOLOGICAL Economies of scale in brewing and distribution The Importance of Competition Whilst the general environment is important, the more immediate environment that surrounds most organisations is the competitive environment. The concern of most managers is upon the ways in which the competitive environment might have upon their own organisations. The foundations of competition as a norm go back to Adam Smith in the eighteenth century and Vilfredo Pareto in the nineteenth. According to these writers, competition potentially offers an optimal state in which resources are efficiently (if not necessarily fairly) allocated. Smith was so struck by the effectiveness of competition that he spoke of its working as an “invisible hand”. Under certain conditions (more or less the absence of barriers to entry) it would guide the selfish actions of individuals to the best outcome for society as a whole. Essentially firms compete in 2 ways: They try to undersell one another and capture markets, customers and profits, through manipulating prices and lowering costs. This is termed “price competition”. They compete through “non-price competition” by differentiating their products, marketing, advertising, promoting, branding and otherwise attempting to retain their own customers and attract their rivals. The fact that some businesses are earning above the normal rate of return for their industry attracts in competitors and imitators. The very process of competition provides a dynamic for the economic system. Entrants competing on price or non-price factors are at the same time a threat to existing competitors, a stimulus to develop new markets and products, and to lower cost processes. As well as providing an incentive or dynamic to the economy, competition provides information about opportunities for gain through the messages of prices and profits. Analysing the Competitive Environment Based on an understanding of this process, Michael Porter, of Harvard University, has built a framework to allow for the analysis of competition within a particular industry. Much of his approach builds on the work of Edward H Chamberlin, also of Harvard University, and Joan Robinson, of Cambridge University, who were pioneer analysts of non-price competition in the 1930s. At the heart of Porter’s work is what economist’s refer to as the Structure-ConductPerformance paradigm. To understand the competitive pressures of an industry you need to focus upon its structure - its underlying economics. Structure of an industry - its underlying economics ----> Conduct ----> of the competitors within the industry Performance the profitability of the competitors & the industry as a whole The underlying economics include such factors as the numbers of competitors and how easy it is for firms to enter or leave the industry. For example, if there are lots of competitors, who can enter or leave the industry easily, who sell similar products and who are fully informed of each others strategies (the economists call this perfect competition), then it is unlikely in the long term that any firm will make massive profits. The competitive process described in the section above will ensure that prices and profits are reduced. In contrast, if there is only one firm in the industry and entry into the industry is difficult (the economists call this perfect monopoly) the profits are likely to remain high, unless customers find alternatives to the product. Whilst these two examples may be the (unrealistic?) extremes, the principle still applies to other industries. Porter goes on to argue that firms who come up with a better strategies than their competitors, by understanding and exploiting the conditions of the industry better than others, might be able to achieve a more profitable position in the long term - he calls this sustainable competitive advantage (of which more next week). What factors affect competition in an industry? Figure 3.6 Five forces analysis Potential entrants Threat of entrants Suppliers COMPETITIVE RIVALRY Buyers Bargaining power Bargaining power Threat of substitutes Substitutes Source: Adapted from M. E. Porter, Competitive Strategy, Free Press, 1980, p. 4. Copyright by The Free Press, a division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. Reproduced with permission. According to Porter, whether an industry produces a commodity or a service, or whether it is global or domestic in scope, competition depends on five forces. These forces, which go beyond the immediate competitors in the industry, are: the threat of new entrants; the existence of substitute products or services; the bargaining power of suppliers; the bargaining power of customers or buyers; existing rivalry within the industry; These five forces determine the ultimate profit potential of an industry as a whole. Within an industry, individual firms who develop particular strengths may be able to gain competitive advantage whatever the profit position of the industry as a whole is. The ultimate strength of competition in an industry depends on the collective strength of these forces: sometimes one will dominate; often it's a collection of two or three. To understand which of these forces is likely to be most significant means investigating the underlying structural conditions that underpin them. We can examine each force in turn, to identify the factors that might be important: Five Forces Analysis (1) The threat of entry ... Dependent on barriers to entry such as: Economies of scale Capital requirements of entry Access to distribution channels Cost advantages independent of size (eg (eg the “experience curve”) Expected retaliation Legislation or government action Differentiation Five Forces Analysis (2) Buyer power is likely to be high when: There is a concentration of buyers There are many small operators in the supplying industry There are alternative sources of supply Components or materials are a high percentage of cost to the buyer leading to “shopping around” Switching costs are low There is a threat of backward integration Five Forces Analysis (3) Supplier power is high when: There is a concentration of suppliers Switching costs are high The supplier brand is powerful Integration forward by the supplier is possible Customers are fragmented and bargaining power low Five Forces Analysis (4) Threat of substitutes Substitutes take different forms: Product substitution Substitution of need Generic substitution Doing without Five Forces Analysis (5) Competitive Rivalry is high when: Entry is likely Substitutes threaten Buyers or suppliers exercise control Competitors are in balance There is slow market growth Global customers increase competition There are high fixed costs in an industry Markets are undifferentiated There are high exit barriers Assessing each of the competitive forces in turn, by identifying the structural factors which are significant in each case, will allow an understanding of the dynamics of the industry (its underlying economics). As well as providing an insight into dynamics of the industry, this approach also allows individual companies to understand the directions from which they face the greatest competitive pressures - and tailor their strategies to meet these pressures. What are the main factors influencing the nature of competition within the European brewing industry? A FIVE FORCES ANALYSIS OF THE EUROPEAN BREWING INDUSTRY Potential Entrants Competitors from Japan or the USA Potential Substitutes Soft drinks e.g. Coca-Cola Wine Other leisure activities e.g. going to the cinema Power of Suppliers Suppliers (e.g. farmers and packaging companies) have little power Power of Customers Customer loyalty to local brews - e.g. Germany Retailers - supermarkets have growing power as industry concentration increases Tied Houses - until recently this was one way of reducing Customer Power in the UK Existing Rivalry Barriers to entry within EU are reducing leading to cross-border mergers Industry concentration across Europe is still relatively low Demand for brewed products is static/declining in most countries Summary Industry restructuring between existing competitors and the growing power of the supermarkets are probably the main competitive forces in the industry at present. Are the factors the same across all countries? Whilst some pressures are best understood on a pan-European level, many of the structural conditions vary between countries - distribution structures and industry concentration being two major factors. So need to apply the 5 Forces Framework both at a pan-European level and at the level of individual countries to gain a full understanding. This example of differences between the pan-European level and individual countries highlights the necessity of understanding how the framework is to be used. Five Forces Analysis: Key Questions and Implications What are the key forces at work in the competitive environment? Are there underlying forces driving competitive forces? Will competitive forces change? What are the strengths and weaknesses of competitors in relation to the competitive forces? Can competitive strategy influence competitive forces (eg (eg by building barriers to entry or reducing competitive rivalry)? The FFF allows the strategist to both understand the dynamics of their industry and to identify ways in which to respond to the pressures and forces identified – to change the strategy of the organisation. How have the different brewing companies chosen to compete within the industry? Whilst the Five Force Framework can give a good insight into the competitive dynamics of a particular industry or sector, most managers also need to understand how their organisation is positioned relative to the other competitors within the industry. Strategic Group Analysis Strategic Group Analysis is useful to: Identify firms with similar strategic characteristics Therefore identify the most direct competitors Identify mobility barriers Identify strategic opportunities (“strategic spaces”) Strategic threats and problems Even within the same industry, not all competitors will be following similar strategies or competing directly against each other. Michael Porter suggests the use of strategic group analysis to identify the ways in which particular groups of companies compete within the industry. The key to this approach is to identify two or three sets of characteristics that seem to establish key differences between the companies or groups of companies. Johnson and Scholes highlight a range of possible characteristics: Figure 3.8 Some characteristics for identifying strategic groups It is useful to consider the extent to which organisations differ in terms of characteristics such as: Extent of product (or service) diversity Extent of geographic coverage Number of market segments served Distribution channels used Extent (number) of branding Marketing effort (e.g. advertising spread, size of salesforce) Extent of vertical integration Product or service quality Technological leadership (a leader or follower) R&D capability (extent of innovation in product or process) Cost position (e.g. extent of investment in cost reduction) Utilisation of capacity Pricing policy Level of gearing Ownership structure (separate company or relationship with parent) Relationship to influence groups (e.g. government, the City) Size of organisation Source: Adapted from M.E. Porter, Competitive Strategy, Free Press, 1980; and J.McGee and H.Thomas, ‘Strategic groups: theory, research and taxonomy’, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 7, no. 2 (1986), pp.141-60. Companies are also unlikely to compete for the same customers. People’s tastes and needs differ, so not all products and services are likely to meet their requirements. By identifying these different requirements through market segmentation analysis, companies can change their strategies to more closely appeal to the needs of particular groups of customers, so defining a position within the market that is more favourable relative to the forces of competition. Again, Johnson and Scholes outline a range of criteria for market segmentation: Figure 3.9 Some criteria for market segmentation Type of factor C onsum er m arkets Industrial/organisational m arkets C haracteristics of people/organisation s A ge, sex, race Incom e Fam ily size Life cycle stage Location Lifestyle Industry Location S ize Technology P rofitability M anagem ent P urchase/use situation S ize of purchase B rand loyalty P urpose of use P urchasing behaviour Im portance of purchase C hoice criteria A pplication Im portance of purchase V olum e Frequency of purchase P urchasing procedure C hoice criteria D istribution channel U sers’ needs and preferences for product characteristics P roduct sim ilarity P rice preference B rand preferences D esired features Q uality P erform ance requirem ents A ssistance from suppliers B rand preferences D esired features Q uality S ervice requirem ents Using both strategic group and market segmentation analysis, we can gain further insight into the major trends affecting the European brewing industry. STRATEGIC GROUPS AND MARKET SEGMENTS IN THE EUROPEAN BREWING INDUSTRY Strategic Groups Two key parameters could be: geographic coverage of the company - from local to pan European or global companies; extent of brand family - from a single product to broad brand family. This leads to an identification of a range of strategic groups: global, broad brand family companies e.g. Carlsberg; European, broad brand family companies e.g. Brasseries Kronenbourg, who are attempting to become more international; international, specialist or narrow brand family, e.g. Grolsch national broad brand family companies e.g. Bass local specialists e.g. many German brewers or UK micro breweries Customer Segments One of the quickest growing sectors in the UK brewing industry, where brewers have traditional links to public houses, is in “themed” family pubs, which provide play areas for children, whilst their parents enjoy a drink. The growth of low alcohol drinks, speciality beers and own-label brands all appeal to different types of customer. Conclusion This session has outlined a number of frameworks and techniques that can be used to assess the external environment facing a particular organisation or understand the dynamics of competition within particular industries or markets. Next week’s session will focus more upon how organisations can outline strategies to meet these challenges of competition.