High Court Judgment: Interlocutory Injunctions Application

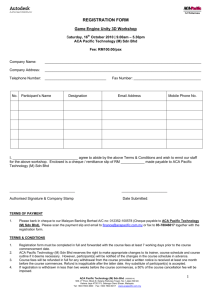

advertisement

IN THE HIGH COURT OF MALAYA AT KUALA LUMPUR (COMMERCIAL DIVISION) CIVIL SUIT NO: 22NCC-249-07/2014 BETWEEN 1. CHIN WAI HONG (No. K/P: 751001-08-5227) 2. BEH LEE LEE (No. K/P: 801027-07-5556) ...PLAINTIFFS AND 1. LIM GUAN HOE (No. K/P: 821202-14-5389) 2. WONG YOKE MEI (No. K/P: 850729-14-5206) ...DEFENDANTS GROUNDS OF JUDGMENT (Plaintiffs’ application for interlocutory injunctions) A. First suit 1. On Wednesday, 9.7.2014, Ms. Beh Lee Lee (Ms. Beh) filed an action in Kuala Lumpur High Court Civil Suit No. 22NCC-24707/2014 (1st Suit) against the following persons: 2 (a) Mr. Lim Guan Hoe (1st Defendant); and (b) Ms. Wong Yoke Mei (2nd Defendant). 2. On the next day, Thursday, 10.7.2014, Ms. Beh made an ex parte application with a certificate of urgency (certified by Ms. Beh’s learned counsel) for, among others, the following orders pending the disposal of the 1st Suit (1st Application): (a) a mandatory injunction to compel the Defendants to hand over “immediately within 24 hours” a resolution (2nd Resolution) of Tian Yik (M) Sdn. Bhd. (TYSB) to Ms. Beh from the date of service of the mandatory injunction; (b) an injunction to restrain “immediately” the Defendants from operating TYSB’s bank accounts and bank facilities (TYSB’s Bank Accounts); (c) a mandatory injunction to compel TYSB to adhere to an earlier resolution of TYSB made in May 2014 regarding the conduct of TYSB’s Bank Accounts (1st Resolution); (d) an injunction to restrain immediately the Defendants from having access to TYSB’s stocks in TYSB’s store (TYSB’s Stocks); and (e) a mandatory injunction to compel the Defendants to cooperate “immediately” with Ms. Beh to pay off TYSB’s debts with TYSB’s funds. 3 3. The cause papers for the 1st Suit and the 1st Application (1st Cause Papers) were brought to my attention at about 3 pm, Thursday, 10.7.2014. After perusing the 1st Cause Papers, at about 3.30 pm the same day, I directed the following (1st Direction): (a) the 1st Cause Papers should be served on the Defendants’ solicitors and if the Defendants were not legally represented, the 1st Cause Papers should be served personally on the Defendants; and (b) the 1st Application be heard inter partes on short notice at 2.30 pm, Monday,14.7.2014. I am aware that Order 32 rule 3 of the Rules of Court 2012 (RC) requires not less than 2 clear days of service of a notice of application. Nonetheless, in view of the fact that a certificate of urgency had been filed in respect of the 1st Application, I directed a hearing of the 1st Application on the following Monday. B. Discontinuance of 1st Suit and commencement of second action 4. Despite the 1st Direction, at about 3.30 pm, Friday, 11.7.2914, I was given – (a) a notice of discontinuance of the 1st Suit filed in the morning on 11.7.2014 which stated that Ms. Beh discontinued the 1st 4 Suit with no order as to costs and with liberty to file afresh (Discontinuance of 1st Suit); (b) a second suit (2nd Suit ) filed by Mr. Chin Wai Hong (Mr. Chin) and Ms. Beh against the Defendants. The contents of the statement of claim (SOC) in the 1st and 2nd Suits are essentially the same except that Mr. Chin is now a coplaintiff with Ms. Beh in the 2nd Suit (Plaintiffs); and (c) a second ex parte application (2nd Application) for the same interlocutory relief as the 1st Application save that Mr. Chin is now a co-applicant with Ms. Beh in the 2nd Application and the affidavit in support had been affirmed by both Plaintiffs (Plaintiffs’ Affidavit). A second certificate of urgency was affirmed by the same learned counsel for the Plaintiffs. The 2nd Application however omitted to state about the 1st Suit, 1st Application, 1st Direction and Discontinuance of 1st Suit (I will discuss about this omission later). 5. The same solicitors acted in the 1st and 2nd Suits. 6. After perusing the cause papers for the 2nd Suit and 2nd Application (2nd Cause Papers), I gave the same direction for the 2nd Cause Papers to be served on the Defendants or their solicitors and for the 2nd Application to be heard inter partes at 2.30 pm, Monday, 14.7.14 (the initial hearing date for the 1st Application). 5 C. Plaintiffs’ claim 7. According to the SOC and the Plaintiffs’ Affidavit – (a) the Plaintiffs are husband and wife. The Defendants are married to each other; (b) each of the Plaintiffs and Defendants holds 25% of the shares in TYSB. Ms. Beh and the Defendants are directors of TYSB; (c) Ms. Beh was tasked with the internal management of TYSB as well as the responsibility to make all purchases for TYSB. The 1st Defendant was in charge of all dealings between TYSB and external parties, including TYSB’s sales; (d) the 1st Resolution provided that TYSB’s Bank Accounts were to be jointly operated by – (i) Ms. Beh; AND (ii) either the 1st or 2nd Defendant; (e) in March 2014, the Plaintiffs and Defendants agreed (Alleged Agreement) – (i) to cease the business of TYSB in June 2014 and to wind up TYSB; 6 (ii) the 1st Defendant was required to sell all of TYSB’s Stocks by June 2014; and (iii) after paying off TYSB’s creditors, any balance of TYSB’s Stocks and cash would be divided to the Plaintiffs and Defendants according to their shareholding; and (f) at about the end of June 2014, the Plaintiffs found out that the Defendants had breached the Alleged Agreement (Alleged Breach) by – (i) substituting the 1st Resolution with the 2nd Resolution without the Plaintiffs’ knowledge and consent; (ii) the 1st Defendant established 2 other entities which conducted the same business as TYSB and took away TYSB’s clients without the Plaintiffs’ knowledge and consent; and (iii) the Defendants had taken away TYSB’s Stocks without the Plaintiffs’ knowledge and consent. 8. It is to be noted that despite the Plaintiffs’ above allegations – (a) the Alleged Agreement and the 1st Resolution were not exhibited in the 2nd Application; and 7 (b) the 2nd Resolution was not signed (Infirmities in Plaintiffs’ Case). D. Hearing of 2nd Application 9. At the hearing of 2nd Application at 2.30 pm, Monday, 14.7.2014, only the Plaintiffs’ learned counsel was present. According to her, the 2nd Cause Papers had only been served on the Defendants’ solicitors in the morning of 14.7.2014. 10. In view of the short service of the 2nd Cause Papers, I directed the hearing of the 2nd Application be adjourned to 3 pm, Friday, 18.7.2014. 11. The Plaintiffs’ learned counsel applied for an ad interim order of all the prayers of the 2nd Application pending the disposal of the 2nd Application. 12. The court clearly has the jurisdiction to grant an ad interim injunction or holding over injunction pending the disposal of the interlocutory injunction application – (a) s 51(1) of the Specific Relief Act 1950 (SRA) provides as follows “Temporary injunctions are such as to continue until a specified time, or until the further order of the court. They may be granted at any period of a suit, and are regulated by the law relating to civil procedure.” (emphasis added); and 8 (b) the Court of Appeal’s judgment in RIH Services (M) Sdn Bhd v Tanjung Tuan Hotel Sdn Bhd [2002] 3 CLJ 83, at 91-92. 13. I declined to grant an ad interim order for reasons which I will discuss later in this judgment. 14. At 3 pm, Friday, 18.7.2014, the Defendants’ learned counsel was not present despite the assurance of the Plaintiff’s learned counsel that the 2nd Cause Papers had been served on the Defendants’ solicitors. 15. I was mindful that the Plaintiffs’ Affidavit had not been rebutted by any affidavit from the Defendants and was therefore deemed to have been accepted by the Defendants (Federal Court’s judgment in Sunrise Sdn Bhd v First Profile (M) Sdn Bhd & Anor [1997] 1 CLJ 529, at 535). Despite the unrebutted Plaintiffs’ Affidavit and the oral submission by the Plaintiffs’ learned counsel, I was unable to accede to the 2nd Application. This is due to the following brief reasons (which I will elaborate below): (a) damages was an adequate remedy for the Plaintiffs in this case; (b) the Plaintiffs did not have an unusually strong and clear case for this court to grant interlocutory mandatory injunctions; 9 (c) the Plaintiffs’ inequitable conduct disentitled them from seeking for the equitable relief of interlocutory injunctions and (d) the 2nd Application sought interlocutory relief in respect of TYSB’s Bank Accounts, TYSB’s Stocks, the 1st and 2nd Resolutions but TYSB had not been sued as a codefendant in this case. E. Remedy of damages is adequate in this case 16. It is clear that in the 2nd Application, the Plaintiffs bear the onus to satisfy the court that the remedy of damages in not an adequate remedy – the Court of Appeal’s judgment in Gerak Indera Sdn Bhd v Farlim Properties Sdn Bhd [1997] 3 MLJ 90, at 99. 17. The sole basis of the Plaintiffs’ claim was the Alleged Breach of the Alleged Agreement. Assuming the averments in the 2nd Application were true, damages for the Alleged Breach was an adequate remedy for the Plaintiffs and hence, the 2nd Application should be refused on this ground alone – (a) the Supreme Court’s judgment in Associated Tractors Sdn Bhd v Chan Boon Heng & Anor [1990] 1 CLJ (Rep) 30, at 32 “… the most important factor to consider as a matter of principle is the question of whether in lieu of the injunction damages would be an adequate and proper remedy because in the matter of injunctions 10 and exercising its jurisdiction the Court acts upon the principle of preventing irreparable damage. As Lindley LJ said in London & Blackwell Rly Co v Cross (1886) 31 Ch D 354 at p. 369: The very first principle of injunction law is that you do not obtain injunctions for actionable wrongs for which damages are the proper remedy.” (emphasis added); (b) the Court of Appeal’s judgment in Hong Huat Sdn Bhd v Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club Sdn Bhd [2001] 1 CLJ 181, at 191 [Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club (No. 1)]; and (c) the Court of Appeal case of Inter Heritage (M) Sdn Bhd v Asa Sports Sdn Bhd [2009] 2 CLJ 221, at 233. F. When should an interlocutory mandatory injunction be granted? 18. In deciding the 2nd Application regarding the prayer for interlocutory mandatory injunctions, the question that arises is what is the test to decide these applications? Is the test to determine interim mandatory injunctions the same for deciding interlocutory restraining injunction applications? 11 19. In Alor Janggus Soon Seng Trading Sdn Bhd & 6 Ors v Sey Hoe Sdn Bhd & 2 Ors [1995] 1 CLJ 461, at 473-474 and 484, the Supreme Court held that in deciding an interim restraining injunction application, the court should consider whether the applicant has raised a serious question to be tried or not (“serious question to be tried” test). 20. For interlocutory mandatory injunctions, the preponderance of appellate decisions in our country apply a higher threshold (as compared to interlocutory prohibitory injunctions). I refer to the following appellate decisions: (a) in Tinta Press Sdn Bhd v Bank Islam Malaysia Bhd [1987] 2 MLJ 192, at 193-194, the Supreme Court decided “The discretionary power of the Court to grant a mandatory injunction is provided by section 53 of the Specific Relief Act 1950 (Act 137). By judicial process, the power is extended to the granting of an interlocutory mandatory injunction before trial. Such discretion however must be exercised and an injunction granted only in exceptional and extremely rare cases as was held in Wah Loong (Jelapang) Tin Mine Sdn Bhd v Chia Ngen Yiok [1975] 2 MLJ 109 and confirmed by the Federal Court in Sivaperuman v Heah Seok Yeong Realty Sdn Bhd [1979] 1 MLJ 150. The case must be unusually strong and clear in that the Court must feel assured that a similar injunction would probably be granted at the trial on the ground that it would be just and equitable that the plaintiff's interest be protected by immediate issue of an injunction, otherwise irreparable injury and inconvenience would result. (See Gibb & Co v Malaysia Building Society Bhd [1982] 1 MLJ 271, 273 and Shepherd Homes Ltd v Sandham [1971] 1 Ch 340, 349).” (emphasis added). 12 It is to be noted that the Supreme Court in Tinta Press Sdn Bhd adopted a more stringent “unusually strong and clear” test (not the “serious question to be tried” test) for interim mandatory injunctions. In respect of this higher threshold for interlocutory mandatory injunctions, Tinta Press Sdn Bhd approved 2 earlier Federal Court judgments in – (i) Gibb & Co v Malaysia Building Society Bhd [1982] 1 MLJ 271, at 273; and (ii) Sivaperuman v Heah Seok Yeong Realty Sdn Bhd [1979] 1 MLJ 150, at 150; (b) in Karuppannan s/o Chellapan v Balakrishnen s/o Subban [1994] 4 CLJ 479, at 487, the Federal Court followed the English High Court case of Shepherd Home Ltd v Sandham [1971] Ch 340 and held that the plaintiff’s case was “unusually clear and sharp” to justify the granting of an interlocutory mandatory injunction in that case; and (c) Tinta Press Sdn Bhd has been applied in, among others, the following Court of Appeal’s decisions – (i) in Foong Seong Equipment Sdn Bhd (receivers and managers appointed) v Keris Properties (PK) Sdn Bhd (No. 2) [2009] 5 MLJ 393, at 399-401 and 405; (ii) Inter Heritage (M) Sdn Bhd, at p. 231-233; and (iii) Timbermaster Timber Complex (Sabah) Sdn Bhd v Top Origin Sdn Bhd [2002] 1 MLJ 33, at 40-41. 21. A slightly different approach was laid down by the Court of Appeal in Marina bte Mohd Yusoff v Pekeliling Triangle Sdn Bhd (receiver and manager appointed) [2008] 1 MLJ 317, at 328, as follows: 13 “In the instant case the remedy which PTSB seeks against MY includes delivery of possession of the said lands and building which in substance is a mandatory interlocutory injunction. Such injunctions are granted on the same basic principles as are prohibitory injunctions, namely there is a question to be tried and the balance of convenience. However in addition the plaintiff, in order to succeed, has to show that his case has a higher probability of success at the trial of the action. This test was adopted in Timbermaster Timber Complex (Sabah) Sdn Bhd v Top Origin Sdn Bhd [2002] 1 MLJ 33 following the English Court of Appeal case of Locabail International Finance Ltd v Agroexport [1986] 1 All ER 901 (see also MBf Holdings Bhd v East Asiatic Co (Malaysia) Bhd [1995] 3 MLJ 49). The rationale given for this different approach is that in the case of a mandatory interlocutory injunction the plaintiff will in substance obtain the reliefs that he seeks in the main action.” (emphasis added). As I have stated above, Timbermaster Timber Complex (Sabah) Sdn Bhd actually applied the “unusually strong and clear” test. I will describe the approach taken in Marina bte Mohd Yusoff as a “higher probability of success” test. 22. A third approach applies the “serious question to be tried” test and does not distinguish between an application for an interlocutory mandatory injunction and an application for an interim restraining order. This approach is illustrated in the following Court of Appeal cases: 14 (a) Hong Huat Sdn Bhd v Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club Sdn Bhd [2001] 1 CLJ 181, at 188-189 and 192 [per Siti Norma Yaakob JCA (as her Ladyship then was)]; and at 195 (per Abu Mansor JCA (as his Lordship then was)] [Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club (No. 1)]; (b) in ESPL (M) Sdn Bhd v Radio & General Engineering Sdn Bhd [2004] 4 CLJ 674, at 691-694, Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as his Lordship then was) decided as follows “As already observed, what the defendant has sought is a mandatory injunction. The question arises: Is the grant of a mandatory injunction governed by principles different from those applicable to prohibitory injunctions? At one time, that was thought to be the case. No longer so. In Films Rover International Ltd and Others v. Cannon Film Sales Ltd [1986] 3 All ER 772, Hoffmann J (as he then was) demolished the myth that there was any difference in the principles applicable to the grant of interlocutory mandatory and prohibitory injunctions. … The views of Hoffmann J have been adopted and applied by our courts and also by the courts of Singapore. See, Timbermaster Timber Complex (Sabah) Sdn Bhd v. Top Origin Sdn Bhd [2002] 1 CLJ 566 (CA); BSNC Leasing Sdn Bhd v. Sabah Shipyard [2000] 2 CLJ 197 (CA); Thomas M Heysek & Anor v. Boyden World Corp [1989] 1 MLJ 219; Singapore Press Holdings Ltd v. Brown Noel Trading Pte Ltd [1994] 3 SLR 151 (CA). 15 It follows that the steps to be followed in an application for a mandatory injunction are the same as those in an application for a prohibitory injunction. Those steps were set out in the judgment of this court in Keet Gerald v. Mohd Noor bin Abdullah & Ors [1995] 1 CLJ 293 …” (emphasis added); and (c) the Court of Appeal held in Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club Sdn Bhd v Hong Huat Sdn Bhd [2008] 6 CLJ 31, at 37 [Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club (No. 2)] – “It is also pertinent to note that in an application for an interlocutory injunction; whether mandatory or prohibitory; the primary question for the court is whether the justice of the case warrants the grant of relief. See, Keet Gerald Francis Noel John v. Mohd Noor bin Abdullah & Ors [1995] 1 CLJ 293. It is upon that issue that this court made its pronouncement in its earlier decision.” 23. I am of the view that the “unusually strong and clear” or “unusually sharp and clear” test (not the “serious question to be tried” test or the “higher probability of success” test) should apply in interlocutory mandatory injunction applications. My reasons are as follows: 16 (a) the “unusually strong and clear” test has been authoritatively laid down, not once but twice by our highest courts. First, by our then apex court, the Supreme Court, in Tinta Press Sdn Bhd and second, by our Federal Court in Karuppannan. Until the Federal Court revisits and overrules Tinta Press Sdn Bhd and Karuppannan, both of these cases are binding on me as a matter of stare decisis. It is to be noted that when the Federal Court decided Gibb & Co and Sivaperuman, appeals could be made to the Privy Council for civil matters. In other words, Gibb & Co and Sivaperuman were not decided by our highest court then; (b) an interlocutory restraining injunction generally preserves the status quo pending the disposal of a suit. Unlike an interim prohibitory order, an interlocutory mandatory injunction usually has the effect of altering the status quo even before the plaintiff goes to trial to prove his or her case. This is because an interim mandatory injunction compels the defendant to do a positive act even before the commencement of the trial of the plaintiff’s suit. Accordingly, a more stringent test should apply to interlocutory mandatory injunction applications vis-à-vis interim restraining injunction applications. Having said that, I acknowledge that there may be exceptional circumstances whereby an interim mandatory injunction is needed to reestablish the status quo ante (the position before the wrong in question has been committed by the defendant); 17 (c) if a lower threshold is applied and an interim mandatory injunction is more “easily” obtained, I am concerned that the interlocutory mandatory injunction may be abused in the following manner – (i) an interim mandatory injunction may be obtained as a “pre-emptive strike” to compel a defendant to comply with that injunction within a short period of time under threat of contempt of court proceedings; and (ii) once the defendant complies mandatory injunction under with pain the of interim committal proceedings, the plaintiff may then proceed to settle the suit on the plaintiff’s terms and need not prove his or her case at trial. An example is this case where the Plaintiffs sought for, among others, an ex parte mandatory injunction to compel the Defendants to hand over the 2nd Resolution within 24 hours from the date of service of that injunction. If I had granted the ex parte mandatory order and if the Defendants did not comply with that order within 24 hours, the Plaintiffs would be entitled to cite the Defendants for contempt of court for breaching that injunction. In such an instance, the Plaintiffs would have an undue advantage against the Defendants even before the hearing of the inter partes interlocutory injunction application! 18 With effect from 1.3.2013, s 65(5)(a) of the Subordinate Courts Act 1948 (introduced by Subordinate Courts (Amendment) Act 2010) confers jurisdiction on Sessions Courts to grant injunctions, including ex parte interlocutory mandatory injunctions (please note the Chief Registrar’s Circular No. 1 of 2013 which provides certain “safeguards” concerning Sessions Court’s power to grant injunctions). As Sessions Court Judges now have the jurisdiction to grant interlocutory mandatory injunctions, it is therefore prudent for a higher threshold to be fulfilled by plaintiffs seeking interim mandatory injunctions; (d) a higher threshold for interim mandatory injunctions is also required in Singapore and India. I will begin with the appellate decisions in Singapore as follows – (i) in NCC International AB v Alliance Concrete Singapore Pte Ltd [2008] 2 SLR 565, at paras 19 and 75, the Singapore Court of Appeal (its apex court) held as follows “19. … We found that the Judge had, in the exercise of his discretion, correctly refused to grant the relief sought, an interlocutory mandatory injunction being, it must be emphasized, a very exceptional remedy. … 75. In any event, an interim mandatory injunction is a very exceptional discretionary 19 remedy. There is a much higher threshold to be met in order to persuade the court to grant such an injunction as compared to an ordinary prohibitive injunction. Case law has established that the courts will only grant an interim mandatory injunction in clear cases where special circumstances exist …” (emphasis added); and (ii) in Chin Bay Ching v Merchant Ventures Pte Ltd [2005] 3 SLR 142, at para 37, the Singapore Court of Appeal held that the court must be satisfied of the existence of special circumstances which warrants the issue of an exceptional relief like an interlocutory mandatory inunction; and (iii) Singapore Press Holdings Ltd was cited in ESPL (M) Sdn Bhd, at p. 694. In Singapore Press Holdings Ltd, at p. 158-160, the Singapore Court of Appeal followed its own earlier decision in Chuan Hong Petrol Station Pte Ltd v Shell Singapore (Pte) Ltd [1992] 2 SLR 729. In Chuan Hong Petrol Station Pte Ltd, at p. 742-744, the Singapore Court of Appeal held as follows “Mandatory guidelines and prohibitory injunctions: the 20 Counsel for the respondents submitted that what the appellants sought, at least as far as the supply contract was concerned, was in the nature of mandatory interlocutory injunctions. He submitted that this being the case, the relevant test was whether the court had a high degree of assurance that at the trial it would appear that the decision of granting the application was rightly made. If, as we understand it, the difference between the two kinds of interim relief lies in whether the status quo is disturbed, it seems clear in this case that what the appellants sought was no more than to preserve the status quo pending final determination of the action, to carry on what they had been doing. In a normal case, following the guidelines in American Cyanamid Co v Ethicon Ltd [1975] AC 396, an interlocutory injunction may be granted on the applicant showing a serious question to be tried. This was in fact the approach taken by the learned judge when he referred to the issues raised by the appellants. It seems to us that the status quo would not be disturbed if it were merely a question of granting the reliefs which the appellants sought. However, when, as was the case, the appellants' application was refused, even without the respondents' application being granted, the effect was to fundamentally alter the status quo. For this purpose, the status quo must be by reference to a time before the respondents stopped supplying fuels to the appellants and before the appellants were compelled to cease operations. The refusal of the appellants' application and the granting of the respondents' application, had a mandatory effect in the real sense of the word. We agree that in such circumstances, more than what is normally required in a case of a prohibitory injunction was required. Counsel mentioned the 'high degree of assurance' test in this connection. We take the opportunity to refer to what has been said in certain recent cases concerning the principles involved. We were referred to the English Court of Appeal decision in Locabail International Finance Ltd v Agroexport & Anor [1986] 1 WLR 21 657, in which the following statement of Megarry J in Shepherd Homes Ltd v Sandham [1971] Ch 340 at p 351 was referred to and applied: ... on motion, as contrasted with the trial, the court is far more reluctant to grant a mandatory injunction than it would be to grant comparable prohibitory injunction. In a normal case, the court must, inter alia, feel a high degree of assurance that at the trial it will appear that the injunction was rightly granted; and this is a higher standard than is required for a prohibitory injunction.’ In the Locabail case [1986] 1 WLR 657, the injunction sought was a mandatory one which, if granted, would amount to granting a major part of the relief claimed in the action. Mustill LJ, following what was said in Shepherd Homes [1971] Ch 340, said that such an application must be approached with caution and the relief granted only in a clear case. These cases and the general question of principle were well analysed by Hoffman J in Films Rover International v Cannon Film Sales Ltd [1987] 1 WLR 670. We respectfully agree with Hoffman J that it is important to distinguish between fundamental principle and what are sometimes described as 'guidelines', ie useful generalizations about the way to deal with the normal run of cases falling within a particular category. We agree with him that a fundamental principle is that the court should take whichever course appears to carry the lower risk of injustice if it should turn out to have been wrong at trial in the sense of granting relief to a party who fails to establish his rights at the trial, or of failing to grant relief to a party who succeeds at the trial. We agree with Hoffman J that the guidelines for the grant of both kinds of interlocutory injunctions are derived from this principle. 22 The 'high assurance' test mentioned by counsel is no more than a generalization, albeit a useful one, of what courts normally do. It is not a principle in the sense of being capable of application in all cases or capable of explaining what courts do in all cases. It is a factor, no doubt often a strong factor, which the court will take into consideration when granting a mandatory injunction. The stronger the case appears at this stage, the lesser the risk of being proved wrong at the trial. However, the court, of necessity, has to consider other relevant factors, such as the conduct of the parties and whether damages instead of an injunction are an adequate remedy. The strength of a party's case (reaching a 'high assurance' or 'clear case' standard) is neither a necessary, nor is it a sufficient, condition for the grant of a mandatory injunction. Thus, in the Films Rover case [1987] 1 WLR 670 itself, although the case was put no higher than an arguable case, Hoffman J, nevertheless, allowed a mandatory injunction on the ground that the risk of injustice to the plaintiffs was greater if the injunction was withheld than the risk of injustice suffered by the defendant if the injunction was granted. On the other hand, in the Shepherd Homes case [1971] Ch 340, there was a clear-cut infringement by the defendant of a restrictive covenant, but the plaintiffs were denied a mandatory injunction to require the defendant to remove a wall erected in breach of the covenant. Megarry J took into consideration, among other things, the fact that the plaintiffs delayed in taking proceedings. He said: 'No doubt a mandatory injunction may be granted where the case for one is unusually sharp and clear; but it is not a matter of course.” (emphasis added). I have cited Chuan Hong Petrol Station Pte Ltd in extenso as the court in that case applied both – 23 (1) the higher threshold for interlocutory mandatory injunctions as held by Megarry J (as his Lordship then was) in the English High Court case of Shepherd Homes Ltd; AND (2) the lower threshold test of a serious question to be tried and which interlocutory decision carries the lower risk of injustice [as decided by Hoffmann J (as his Lordship then was) in the English High Court in Films Rover International Ltd v Cannon Film Sales Ltd [1986] 3 All ER 772]. In Films Rover International Ltd, at p. 780-782, an interim mandatory injunction was granted despite the plaintiff not having a “high degree of assurance” of success because the risk of injustice to the plaintiff was greater if the interlocutory mandatory injunction was withheld than the risk of injustice suffered by the defendant if that injunction was granted. It is to be noted that the Court of Appeal in ESPL (M) Sdn Bhd, at p. 694, relied on Films Rover International Ltd. It is however clear that the more recent Singapore Court of Appeal’s decisions in NCC International AB and Chin Bay Ching have adopted a higher threshold for interlocutory mandatory injunctions circumstances; and by requiring proof of special 24 (e) in India, a higher threshold is required. Suffices for me to cite 2 decisions of the Indian Supreme Court as follows – (i) Dorab Cawasji Warden v Coomi Sorab Warden & Ors AIR 1990 SC 867, at 871-874 (paras 10-15), the Indian Supreme Court considered both Shepherd Homes Ltd and Films Rover International Ltd and yet held that for an interlocutory mandatory injunction, the plaintiff should have “a strong case for trial … it shall be a higher standard than a prima facie case that is normally required for a prohibitory injunction”; and (ii) in Kishore Kumar Khaitan & Anor v. Praveen Kumar Singh AIR 2006 SC 1474, at 1476-1474 (para 5), P.K. Balasubramanyan J delivered the Indian Supreme Court’s judgment as follows – “An interim mandatory injunction is not a remedy that is easily granted. It is an order that is passed only in circumstances which are clear and the prima facie materials clearly justify a finding that the status quo has been altered by one of the parties to the litigation and the interests of justice demanded that the status quo ante be restored by way of an interim mandatory injunction.” (emphasis added). 25 Indian cases are significant as Part 3 of our SRA (ss 50-55) providing for injunctions is based on the Indian Specific Relief Act, 1877 (now the Indian Specific Relief Act 1963). 24. The possible problem of enforcing and/or supervising the enforcement of an interlocutory mandatory injunction, in my view, is not relevant to decide whether a higher or lower threshold should apply. If there is any problem in enforcing and/or supervising the enforcement of an interlocutory mandatory injunction, then the court may decline to grant that interlocutory mandatory injunction on the ground that the balance of convenience is not in favour of such an interlocutory relief. 25. It is to be noted that the Court of Appeal in Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club Sdn Bhd (No. 1), ESPL (M) Sdn Bhd and Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club Sdn Bhd (No. 1) did not refer to Tinta Press Sdn Bhd and Karuppannan. 26. I am of the view that Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club (No. 1) may be explained on the following grounds: (a) in Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club (No. 1), the appellant company applied for an interlocutory mandatory injunction to direct the respondent company to remove all barriers leading to the respondent company’s land and to allow the appellant company access to that land so that the 26 appellant company could continue with its sand mining operations (at p. 188-189); (b) the High Court dismissed the interim mandatory injunction on the ground that the appellant company “had failed to show that its case was unusually sharp and clear to warrant the grant of an interlocutory mandatory injunction in its favour” (at p. 194-195 and 196). In other words, the learned judge applied the more stringent test in respect of interlocutory mandatory injunctions; and (c) the Court of Appeal affirmed the High Court’s dismissal of the interim mandatory injunction application on the ground that the appellant company had no right to be on the respondent company’s land and hence, there was no serious question to be tried (at p. 191-192 and 196-197). 27. Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club (No. 2), at p. 36, concerned an appeal after trial and not the merits of an interlocutory mandatory injunction application. The appeal to the Court of Appeal against the High Court’s refusal to grant an interim mandatory injunction had already been decided in Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club (No. 1). As such, I am of the respectful view that the dicta expressed in Golden Vale Golf Range & Country Club (No. 2) concerning interlocutory mandatory injunctions is obiter. 27 28. The Court of Appeal in ESPL (M) Sdn Bhd, at p. 694, referred to Timbermaster Timber Complex (Sabah) Sdn Bhd, BSNC Leasing Sdn Bhd v Sabah Shipyard [2000] 2 CLJ 197, Singapore Press Holdings Ltd and Thomas M Heysek & Anor v Boyden World Corporation [1989] 1 MLJ 219. It is pertinent to note that (a) Timbermaster Timber Complex (Sabah) Sdn Bhd, at p. 40-41, applied a higher threshold; (b) BSNC Leasing Sdn Bhd, at p. 206, concerned an application for an injunction to restrain the appellant company from prosecuting legal proceedings in Equador or in any jurisdiction concerning a turbine (anti-suit injunction application). In BSNC Leasing Sdn Bhd, there was no application for an interim mandatory injunction; and (c) as explained above, Singapore Press Holdings Ltd, at p. 158-160, adopted Chuan Hong Petrol Station Pte Ltd, at p. 742-744, which applied both the “high degree of assurance” test and the lower threshold. Similarly in Thomas M Heysek, at p. 222-223, the Singapore High Court applied both tests. No preference for either the higher or lower threshold test was expressed in Chuan Hong Petrol Station Pte Ltd, Singapore Press Holdings Ltd and Thomas M Heysek. F1. The English position 29. In England, 2 earlier Court of Appeal decisions favoured a higher threshold. These cases are - (a) in Astro Exito Navegacion SA v Southland Enterprise Co Ltd & Anor (No 2) (Chase Manhattan Bank NA Intervening) [1982] QB 1248, at 1269, the Court of Appeal 28 upheld the High Court’s granting of an interlocutory mandatory injunction on the ground that the plaintiff had a prima facie right to specific performance of the contract in question against the first defendant. This decision was affirmed by the House of Lords on appeal in [1983] 2 AC 787 but there was no discussion by the House of Lords regarding interlocutory mandatory injunctions. It is to be noted that Astro Exito Navegacion SA did not discuss Shepherd Homes Ltd; and (b) in Locabail International Finance Ltd v Agroexport & Ors, The Sea Hawk [1986] 1 All ER 901, at 905-906, the English Court of Appeal expressly followed the “high degree of assurance” test in Shepherd Homes Ltd and set aside the High Court’s interlocutory mandatory injunction (directing the appellant company to pay money to the respondent company). Mustill LJ (as his Lordship then was), at p. 905 and 906, held that the High Court erroneously applied a lower test of “fairly arguable case” which was “a lesser degree of conviction than … was appropriate”. 30. In Films Rover International Ltd, at p. 780-782, Hoffmann J held that Shepherd Homes Ltd and Locabail International Finance Ltd did not lay down principles but only guide-lines which were derived from the “fundamental principle” that the court should take whichever course which carries a lower risk of injustice. Hence, once a plaintiff has raised a serious question to be tried, whether the court will grant an interlocutory mandatory 29 injunction depends on whether the grant of an interlocutory mandatory injunction will carry a lower risk of injustice or not. Film Rover International Ltd has been followed in the following English appellate decisions (a) by Lord Jauncey in the House of Lords’ case of R v Secretary of State for Transport, Ex parte Factortame Ltd & Ors (No. 2) [1991] AC 603, at 676 and 682-683; (b) by Staughton LJ in the Court of Appeal case of Channel Tunnel Group Ltd & Anor v Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd & Ors [1992] 2 All ER 609, at 626, who felt “bound to say that in view of great harm to [plaintiff] which might ensue if an [interlocutory mandatory] injunction were not granted, this might well be a case where it was not essential for a strong probability of success to be shown”. It is to be noted that the Court of Appeal did not grant an interlocutory mandatory injunction in Channel Tunnel Group Ltd, at p. 624, due to the application of the rules of private international law in that case. The Court of Appeal’s decision in Channel Tunnel Group Ltd has been affirmed by the House of Lords in Channel Tunnel Group Ltd & Anor v Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd & Ors [1993] 1 All ER 664, at 690, where Lord Mustill held as follows – “I also accept that it is possible for the court at the pretrial stage of a dispute arising under a construction contract to order the defendant to continue with a 30 performance of the works. But the court should approach the making of such an order with the utmost caution, and should be prepared to act only when the balance of advantage plainly favours the grant of relief.”; (c) in Leisure Data v. Bell [1988] F.S.R. 367, the Court of Appeal applied a lower threshold in the following judgments - (i) Dillon LJ (as his Lordship then was) held “The court has to keep firmly in mind the risk of injustice to either party. Beyond that, there are many cases where there is a salvage element involved, and where it is necessary that some form of mandatory order shall be made to deal with a situation which cannot on the practical realities of the situation be left to wait until the trial. Here the court will act whether or not the high standard of probability of success indicated by Megarry J [in Shepherd Homes Ltd]”; and (ii) Neill LJ stated that – “… the balance that one is seeking to make is more fundamental, more weighty, then mere 'convenience'. I think that it is quite clear from both cases that, although the phrase may well be substantially less elegant, the 'balance of the risk of 31 doing an injustice' better describes the process involved.”; and (d) Zockoll Group Ltd v Mercury Communications Ltd [1998] FSR 354. 31. It seems to me that the present English decisions favour Film Rover International Ltd. In National Commercial Bank Jamaica Ltd v Olint Corporation Ltd [2009] 1 WLR 1405, at 1409-1410, on an appeal from Jamaica, the Privy Council in an opinion given by Lord Hoffmann, approved Film Rover International Ltd. 32. Despite my preference for a higher threshold as decided in Shepherd Homes Ltd, I think Film Rover International Ltd can be understood, if not justified, on the ground that an interlocutory mandatory injunction was given in that case to restore the status quo ante (the position before the commission of the wrong by the defendant company). In Film Rover International Ltd, the defendant company agreed to deliver dubbing material to the plaintiff company so as to enable the plaintiff company to dub and distribute a number of films. After sending some dubbing material for the first few films, the defendant company wanted to “re-negotiate” the contract and consequentially refused to deliver those materials. An interlocutory mandatory injunction was ordered in Film Rover International Ltd to compel the defendant company to deliver the dubbing material to the plaintiff company so that the plaintiff 32 company could dub and distribute the films in question. The interlocutory mandatory injunction ordered in Film Rover International Ltd, in my opinion, a was “restorative” interlocutory mandatory injunction, an order which restored the status quo ante after the defendant company had earlier wrongfully altered the status quo – please see the Indian Supreme Court’s judgment in Kishore Kumar Khaitan, at 14761474 (para 5). F2. The Australian position 33. The earlier Australian cases as follows applied a higher threshold for interim mandatory injunctions: (a) in State of Queensland v Australian Telecommunications Commission (1985) 59 ALR 243, at 245, Gibbs CJ sitting alone in the High Court of Australia (the apex court in Australia) refused to grant an interlocutory mandatory injunction by following Shepherd Homes Ltd and held as follows – “Although, as I have already indicated, there is a serious question to be tried in the present case, I lack a “high degree of assurance” that the plaintiff will necessarily succeed …” (emphasis added); and 33 (b) the “high degree of assurance” test was applied in the following Australian cases – (i) by Northrop J in the Federal Court of Australia (court of first instance in Australia) in Australian National Airlines Commission v Commonwealth of Australia & Ors (1986) 66 ALR 545, at 552; and (ii) by Foster J in the Federal Court case of Midland Milk Pty Ltd & Ors v Victorian Dairy Industry Authority (1987) 82 ALR 279, at 291. 34. Subsequent Australian cases, beginning with Gummow J in the Federal Court in Businessworld Computers Pty Ltd v Australian Telecommunications Commission (1988) 82 ALR 499, at 502-504, followed Films Rover International Ltd and not State of Queensland v Australian Telecommunications Commission and Australian National Airlines Commission v Commonwealth of Australia. Businessworld Computers Pty Ltd was followed in the following Australian cases: (a) Hely J in the Federal Court in South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Ltd v News Ltd & Ors (1999) 169 ALR 120, at 127; and (b) Sackville J in Australian Rugby Union Ltd v Hospitality Group Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1136, at paras 30 and 31. 34 F3. Application of a higher threshold together with other considerations 35. Whichever test the court takes, be it the “unusually strong and clear” test or the “serious question to be tried” approach, it is to be emphasised that the court also needs to consider two additional questions, namely the balance of convenience and whether policy or equitable considerations apply to bar equitable relief. 36. If my view regarding the “unusually strong and clear” test is correct, in considering an interlocutory mandatory injunction, the court should decide the following: (a) whether remedy of damages is an adequate remedy for the plaintiff; (b) whether the plaintiff has established an unusually strong and clear case to justify the granting of an interim mandatory injunction; (c) whether the balance of convenience is in favour of granting an interlocutory mandatory injunction or otherwise; AND (d) whether the plaintiff is disentitled by policy or equitable considerations from being granted an interim mandatory injunction. 35 G. Plaintiffs had no unusually strong and clear case 37. In view of the Infirmities in Plaintiffs’ Case, I do not think the Plaintiffs have an unusually strong and clear case. On this ground alone, I will decline the prayers in the 2nd Application for interlocutory mandatory orders. H. When should an interlocutory injunction be applied ex parte? 38. As 2 successive ex parte interlocutory injunction applications have been made to me, it is necessary to discuss when should such applications be made and how should the court respond? 39. In Sigma Elevator (M) Sdn Bhd v Bahagia Indah Properties Sdn Bhd, Company’s Winding Up No. 28 NCC-1045-11/2013, [2014] AMEJ 872, I stated as follows: “16. Mahkamah ini berpendapat bahawa sesuatu pihak hanya berhak untuk memohon secara ex parte apabila undangundang prosedur yang berkenaan membenarkan secara nyata permohonan sedemikian, contohnya Aturan 29 kaedah 1(2) Kaedah-kaedah Mahkamah 2012 (KM). Andai kata undang-undang bertulis yang berkenaan tidak memperuntukkan pemfailan permohonan ex parte, permohonan sedemikian tidak boleh dibuat walaupun keadaan terdesak. Dalam keadaan terdesak dan bila undang-undang prosedur tidak membenarkan 36 permohonan ex parte, pihak yang berkenaan, pada pendapat saya, seharusnya – (a) memfailkan suatu perakuan segera yang diperakukan oleh peguam bela atau peguam cara yang mewakili pemohon dengan alasan-alasan kenapa pendengaran permohonan tersebut harus disegerakan (sila lihat Nota Amalan No. 3/1985). Perakuan segera itu tidak boleh diperakukan oleh calang-calang peguam yang tidak mewakili pemohon (walaupun mengamal undang-undang dalam firma yang sama dengan peguam bela atau peguam cara yang mewakili pemohon). Andai kata pemohon tidak diwakili peguam, pemohon dikehendaki mengikrarkan suatu affidavit yang mengesahkan alasan-alasan kenapa pendengaran permohonan tersebut harus disegerakan; (b) memohon singkatan tempoh masa (abridgment of time) untuk menyampaikan kertas kausa di bawah Aturan 3 kaedah 5(1) KM; dan (c) pada pendengaran inter partes permohonan tersebut, walaupun terdapat penyampaian singkat (short service), atas kepentingan keadilan dan memandangkan wujudnya keadaan terdesak, pemohon boleh memohon perintah ad interim sementara menunggu perlupusan permohonan tersebut (sila lihat penghakiman Mahkamah Rayuan dalam kes dalam RIH Services (M) Sdn. Bhd. lwn Tanjung Tuan Hotel Sdn. Bhd. [2002] 3 CLJ 83, di 91-92). 37 17. Andai kata permohonan undang-undang prosedur dibuat ex secara membolehkan parte, permohonan sedemikian tidak harus disalahgunakan dan hanya boleh didengar secara ex parte dalam hal keadaan yang terkecuali (exceptional). Dalam kes Permodalan MBF Sdn. Bhd. lwn Tan Sri Datuk Seri Hamzah Abu Samah [1988] 1 CLJ (Rep) 244, di 246, Mahkamah Agung memutuskan bahawa secara amnya, suatu permohonan harus didengar secara inter partes manakala pendengaran permohonan secara ex parte merupakan suatu kekecualian “Inter-party hearing appears to be the rule while an ex parte application for injunction appears to be the exception in the circumstances provided by [the then O 29 r 1(2) and (3) of the Rules of the High Court 1980] and is to be allowed only in cases of urgency on the application of the plaintiff”. 18. Dalam kes Million Group Credit Sdn. Bhd. lwn [1985] CLJ (Rep) 575, di 578, Shankar H (seperti YA adalah pada ketika itu) memutuskan yang berikut: “… in these modern days of swift communication, ex-parte applications should be the exception rather than the rule.” Berdasarkan nas Million Group Credit Sdn. Bhd., dengan penggunaan luas emel dan telefon bimbit yang mempunyai akses kepada emel, secara amnya sesuatu 38 permohonan kepada mahkamah harus didengar secara inter partes. 19. Mahkamah Rayuan dalam kes Motor Sports International Ltd. (Servants or agents at Federal Territory of Labuan) lwn Delcont (M) Sdn. Bhd. [1996] 2 MLJ 605, di 611, melalui suatu penghakiman yang diberi oleh Gopal Sri Ram HMR (seperti YA adalah pada ketika itu), telah memberi panduan yang berikut: “The provisions of O 29 r 2A [Rules of the High Court 1980] were introduced by amendment to ensure that ex parte injunctions of any sort were not granted wily-nilly, but only in cases where they were truly called for.” 20. Berlandakan nas-nas di atas, apabila undang-undang prosedur membenarkan permohonan dibuat secara ex parte, permohonan sedemikian sayugianya dibuat dalam hal keadaan yang berikut: (a) apabila tujuan permohonan tersebut tidak boleh dicapai dengan memberi notis permohonan tersebut – sila lihat penghakiman Mahkamah Tinggi dalam kes Pacific Center Sdn. Bhd. lwn United Engineers (M) Bhd. [1984] 2 MLJ 143, di 146. Contoh-contoh lazim di mana permohonan ex parte perlu dibuat ialah bila perintah-perintah Anton Piller dan Mareva dipohon; DAN (b) keadaan terdesak. perakuan segera Sehubungan daripada dengan peguam bela ini, atau peguam cara pemohon yang mengandungi alasanalasan kenapa pendengaran permohonan perlu 39 disegerakan, mahkamah penting untuk membolehkan mempertimbangkan sama ada permohonan tersebut - (i) harus didengar secara ex parte; (ii) didengar secara ex parte dalam kehadiran peguam bela pihak penentang (opposing party). Dalam keadaan ini, mahkamah boleh mengarahkan notis permohonan ex parte diberi kepada peguam Pendengaran cara sedemikain pihak penentang. disifatkan dalam undang-undang kes sebagai “opposed ex parte” – sila lihat penghakiman Mahkamah Rayuan dalam kes Datuk M.Kayveas lwn PV Das (untuk beliau sendiri dan bagi pihak Parti Progresif Rakyat Malaysia) [1997] 3 MLJ 671, di 678; ATAU (iii) harus didengar secara inter partes dan dalam hal ini, notis pendengaran permohonan tersebut bersamasama dengan segala kertas kausa harus diserahkan kepada peguam cara pihak penentang – sila lihat keputusan Mahkamah Rayuan dalam kes Chellapa a/l K. Kalimuthu (menyaman sebagai pemegang jawatan Kuil Sri Maha Mariamman, HICOM, Shah Alam) lwn Sime UEP Properties Bhd. [1998] 1 MLJ 20, di 25-26.” 40. In summary, I express the following view in Sigma Elevator (M) Sdn Bhd: 40 (a) an application can only be made ex parte if the law expressly provides for it. In the case of interlocutory injunctions, Order 29 rule 1(2) RC provides that “where the case is one of urgency”, interlocutory injunction applications may be made ex parte; (b) despite the urgent nature of the interlocutory injunction application in question, ex parte interlocutory injunction applications should only be made when “it is genuinely impossible to give notice without defeating the purpose of the order” (please see Pacific Center Sdn Bhd lwn United Engineers (M) Bhd [1984] 2 MLJ 143, di 146). Applications for Anton Piller and Mareva orders, by their very nature, have to be made ex parte. After my decision in Sigma Elevator (M) Sdn Bhd, my research reveals that the Privy Council’s opinion (on an appeal from Jamaica) in National Commercial Bank Jamaica Ltd, at p. 1408 (para 13), supports the requirement to give notice of an interlocutory injunction application, no matter how urgent, to the defendant – “… there appears to have been no reason why the application for an injunction should have been made ex parte, or at any rate, without some notice to the bank. Although the matter is in the end one for the discretion of the judge, audi alteram partem is a salutary and important principle. Their Lordships therefore consider that 41 a judge should not entertain an application for which no notice has been given unless either giving notice would enable the defendant to take steps to defeat the purpose of the injunction (as in the case of a Mareva or Anton Piller order) or there has been literally no time to give notice before the injunction is required to prevent the threatened wrongful act. … Their Lordships would expect cases in the latter category to be rare, because even in cases in which there was no time to give the period of notice required by the rules, there will usually be no reason why the applicant should not have given shorter notice or even made a telephone call. Any notice is better than none.” (emphasis added); (c) if the purpose of an interlocutory order will not be defeated if an inter partes application is made (as held in Pacific Center Sdn Bhd), that application should be not be made ex parte even though there are “urgent” and compelling circumstances because – (i) the plaintiff may apply to court under Order 3 rule 5(1) RC to abridge time for short service of the application in question on the defendant; and 42 (ii) when the court fixes an early date to hear the inter partes interlocutory injunction application (presumably on a certificate of urgency filed by the plaintiff’s solicitor or counsel), the plaintiff may apply for an ad interim mandatory injunction in the defendant’s presence (please see RIH Services (M) Sdn Bhd, at p. 91-92); and (d) even if the court hears an ex parte interlocutory injunction application, the court has the discretion to direct the plaintiff to inform the defendant so that the application in question may proceed on an “opposed ex parte” basis as explained by the Court of Appeal in Datuk M.Kayveas v PV Das (for himself and on behalf of People’s Progressive Party of Malaysia) [1997] 3 MLJ 671, di 678. I. Plaintiffs’ inequitable conduct disentitled them from claiming for equitable relief 41. It is trite law that the court may exercise its discretion to decline equitable relief to a plaintiff who has been guilty of inequitable conduct – the High Court’s judgment in Natseven TV Sdn Bhd v Television New Zealand Ltd [2001] 4 AMR 4648, at 4666. 42. I am of the view that the Plaintiffs have been guilty of the following inequitable conduct which disentitled them from making the 2nd Application: 43 (a) the 2nd Application concealed the following material facts (i) the filing of the 1st Suit and the 1st Application; (ii) the 1st Direction; and (iii) Discontinuance of 1st Suit (Plaintiffs’ Concealment); (b) despite the 1st Direction, the Plaintiffs still persisted to file the 2nd Application on an ex parte basis! If the 2nd Suit had been heard by another court, that court would not know about the 1st Direction in view of the Plaintiffs’ Concealment; and (c) the Discontinuance of the 1st Suit and the subsequent speedy filing of the 2nd Suit, support the inference that the Plaintiffs have been guilty of “forum-picking”. This is because Mr. Chin could be easily added as a co-plaintiff in the 1st Suit under Order 15 rule 6(2)(b)(i) and/or (ii) RC. There was therefore no need for the Discontinuance of the 1st Suit, especially when the hearing date for the 1st Application (on the following Monday) had already been fixed on an urgent basis. J. TYSB is not cited as a co-defendant 43. It is trite law that generally, the court cannot make an order against a non-party – the Court of Appeal’s judgment in Re Thien Kon Thai [2008] 6 MLJ 278, at 282. 44. In this case, the 2nd Application applied for interlocutory mandatory and prohibitory injunctions regarding TYSB’s Bank Accounts, TYSB’s Stocks, 1st and 2nd Resolutions. It was therefore necessary for the Plaintiffs to cite TYSB as a co- 44 defendant because the 2nd Application would directly and adversely affect TYSB. The Plaintiffs did not explain in the Plaintiffs’ Affidavit why TYSB was not made a co-defendant in this case. Accordingly, the non-joinder of TYSB as a codefendant in the 2nd Suit is fatal to the 2nd Application. K. Court’s decision 45. Based on the aforesaid reasons, I not only refused to grant an ad interim order but I also dismissed the 2nd Application. I made no order regarding costs of the 2nd Application in view of the fact that the Defendants’ learned counsel was not present. 46. In the interest of justice, I direct an early trial of This Suit (as was directed in Associated Tractors Sdn Bhd, at p. 32). WONG KIAN KHEONG Judicial Commissioner High Court (Commercial Division) Kuala Lumpur DATE: 6 AUGUST 2014 For the Plaintiffs: Cik Wahidah binti Bakhtiar (Messrs Lee & Lim) For the Defendants: Not present 45 Postscript 1. After completing this judgment on 6.8.2014, I have been informed by my learned Deputy Registrar on 7.8.2014 of the following: (a) in view of my direction for an early trial of the 2nd Suit, the case management of the 2nd Suit had been fixed on 25.7.2014; and (b) on 25.7.2014, the Plaintiffs filed a notice of discontinuance of the 2nd Suit with liberty to file afresh and with no order as to costs (Discontinuance of 2nd Suit). 2. The Discontinuance of 2nd Suit, regrettably, substantiated the concern in this case, that there might have been an abuse of the ex parte interlocutory mandatory injunction procedure in particular and an abuse of court process generally. WONG KIAN KHEONG Judicial Commissioner High Court (Commercial Division) Kuala Lumpur DATE: 12 AUGUST 2014