Introduction I) History of shintoism We don't know exactly when this

Introduction

Shintoism or Shinto ( 神道 ) is the fundamental religion of Japan. If we study the etymology of the word, we find “shen” which means “ethos” or

“divinity” and “tao” which means “way”. So,

Shinto is the way of gods, the way of divinities.

It’s one of the last animist religions in the world and it’s articulated around gods called kami.

These kamis are represented everywhere in the nature, in every rocs, mare, tree or animal. This is the native religion of Japan, one of the most important countries of the world so we think it’s very interesting to understand how this philosophy impacts on the Japanese society. We are going to present you, in a first time, the history of Shinto. Afterwards, we will study the shintoism ideology and at last, we will saw practices, rituals and events of this religion.

I) History of shintoism

We don’t know exactly when this religion began. Nobody knows when this kamis belief, Shinto was born. There are only suppositions which say that on the end of the

Yaoji culture (from 300 A.C to 300 B.C) appeared elements which remind some fundamental aspects of Shinto. But perhaps fundaments date of Jomon culture, even more old (from 11 000 to 300 A.C). Indeed, this population made “dogu” which are statuettes of women. We supposed that this belief is the worship of fertility. However, with Yaoji culture appeared a Shinto iconography more conspicuous. Among objects discovered in graves of the first rice cultivators, we found little objects which represent grain warehouse. So, introduction of rice culture seemed had brought with it rituals bonded to harvest-field. These rituals are probably the origin of Shinto. Some experts say that there was another event which found this animist religion: the invasion of Japan in the 4 th century of cavaliers arriving from Central Asia. They brought news

rituals, sepultures emerged especially around the war chief. In conclusion, we could say that the origin of Shinto isn’t known and it’s not the result of the evolution of only one older belief. Shinto is a melting between three religions which are animism, shamanism and worship of elders. Until first contacts with the Chinese civilization, Shinto was this mix of beliefs, of rituals and practices. The development of the religion began in 552, thanks to China who introduce Buddhism. This event had two consequences: on the one hand, there was an amalgam between these religions which is still present today. And on the other hand, Japans had a reaction of defense, on the origin of the development of

Shinto. Then, this religion becomes organized close to the 7 th century.

Myths were unified and every kami which before were only sacred in one or two villages were empowered gods of the nation. From this moment, history of Japan was a succession of opposed movements. Each sovereign imposed the other religion to his population, even if Buddhism was more important than the Shintoism for one millennium. It’s only with the emperor Motoori Norinaga (opposite) that Japanese were again interested by the Kojiki and the Nihonshoki and others older texts of Shinto. One century later, this revival for Shinto is the origin of the restoration of imperial power with Emperor Meiji.

With this emperor, Japan open up himself to occidental civilization and government decided the separation between Shinto and Buddhism. So, in the following years, Shinto took different forms and became the only official religion of

Japan whom the most important was called “Shinto government” and Buddhism which had a strongly development, encounter more problems. The first form is Shinto of the

Imperial House which contained an adoration of the sun goddess, Amataresu. This worship, once public is nowadays totally private. Then there was, Shinto of sects which born in 19 th century. The most famous, the Tenrikyo was founded by a woman and it still exists today with about 3 millions of followers. At last, there was the “Shinto government” which was the most important and its aim is to reinforce the power of the

emperor. Indeed, this institution existed in order to confirm the Japanese identity and the devotion towards the Emperor Meiji. At this moment, the myth of the divine origin of the Emperor was on its paroxysm. Shinto stays the official religion until 1945, until

Japan lost in World War 2. Shinto was dismembered but the two religions which are

Buddhism and Shinto conserved their stability. Since 1945, no religions have an official status.

Today, even if Shinto is less present in Japan, it continues to affect every part of

Japanese life. For instance, sumo which is the national sport of Japan, arise from an ancient ritual gracing kamis: we could notice that the fourposter bed overhead the ring remind a Shinto temple, the referee is wearing a rose dress like Shinto priests, sumo wrestlers swing their legs in order to squash Evil forces and particularly the aspersion of salt of the ring before every match are an ancient ritual of purification.

Fight between two Japanese sumo wrestlers

In the same idea, the Nô Theater, founded in the 15 th century is only the tale of stories of Shinto inspiration. L’ikebama, art to dispose flowers, has also an origin Shinto.

Flowers must be disposed particularly, in order to recreate tree plans of Heaven,

Human being and Earth. Bath appeared like a symbol of communion with nature too.

In the recent history of Japan, we notice the multiplication of shinko shukyo, word which designates new sects appeared in the mid 50’s. Today, Shinto is still present but has to be comprised with other religions like Buddhism and even Christianity, introduced in Japan on 1549. In addition, nowadays, practice of Shinto doesn’t imply a particular belief. Japans don’t believe in kamis like into the past. However, they continue to

celebrate Shinto celebrations because it for them the expression of their belonging to the national community and their will to keep the harmony into the world.

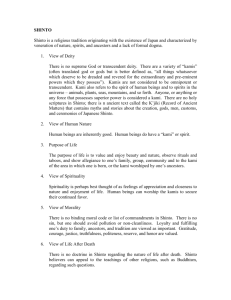

II) Theology of Shinto:

Like in many religions, Shinto considers the idea that there is a superior reality or divine reality. Japanese honor kamis who protect humans’ community. According to the

Kojiki, one of the sacred books, there is close to 8 million of kamis. These divinities live in sacral places dispatched in rural landscape. In the majority, Japanese built a shrine which they called a jinja, a simple construction in wood with a portico, the torii. In this sanctuary, the priest, the kannushi made rituals. For the most part of time, these are purifications. Kamis are everywhere; from the kitchen to the water closet, in animals, in vegetables, in water, in earth. Shinto worship had awarded a divine nature to all stuff which gives admiration or fear.

Many kamis came from the sky and go down, go to the Earth regularly in order to visit shrines and sacral places. Their sacrality is so high that we must respect some ritual before enter into a sanctuary like purification.

Some kamis are good divinities and their origins are Buddhist or Taoist, others are devils which are reckoned as responsible of many mortal diseases. In Japanese tradition, the most evils which are called oni are invisible. Some are presented like animals which can take possession of a person. In this case, in order to get rid of this bad god, we need a priest to exorcise it. The most terrifying evil is the ethos of fox which, according to the tradition is on the origin of death and illness. However, Shinto doesn’t believe in an absolute separation between wrong and well. Every phenomenon can be positive or negative, it depends only on circumstances. So, in the teeth of their ill wills, oni are ambivalent personage. Indeed, for instance, the ethos of fox is associated to another kami which is Inari, god of rice, a very nice kami very popular.

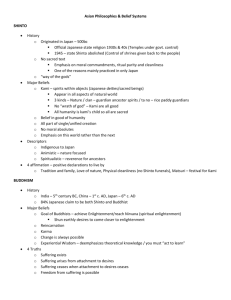

Representation of a tengu

Another example: tengus, these men with heads of birds are oni but they can be also benevolent guardians of a kami and for this reason they are celebrated in Shinto parties that we develop later. In every case, misfortunes which are meted out by onis are seen like actions resulting of a bouleversement of the natural order and not like the manifestation of a specific bad ethos.

Ancestral ethoses constitute also another important category of kami. In Shinto tradition, the spirit of a person after his death becomes a kami and every family in

Japan venerate their kami in private sanctuaries.

At last, kamis which are the most important and the most known are anthropomorphic gods and goddesses appeared during which Japanese called in bygone texts the “God Age”. This time of origins, when divinities lived on the Earth and before they imposed the reign of human descendants, emperors are told in the tale of Kojiki and Nihonshoki. In these sacred books, it also narrated the history of Gods. They told that at the beginning, when world was in chaos, in absolute instability, there was a succession of seven invisible kamis. In the eighth generation, were born the divinity

Izanagi and his sister, the goddess Izanami. From the sky where they lived, they threw a spear and this created an island, Onorogo, the first earth. Two divinities came down on this island and at this moment, they awaked they were totally different and had sexual intercourses. Izanami give birth but it was a monster, a baby who had characteristics of a leech. So they made again the experience and Izanami give birth to many kamis but also to islands which made the Japanese archipelago. But her last child, the fire God killed her and she lowered in country of Yomi, country of deceases. Her husband tried to help his wife to left this country but he failed. Furthermore, he had to run away because he was hunted by Yomi’s witches and he had difficulties to save himself. Later, in order to purify him to soiling, Izanagi bathed in sacred river Hi.

During he washed himself, Amataresu, the sun goddess spring from his right eye, the moon god Tsukiyomi from his left eye and Susanoo which is the god of storm from his nose.

Later, history said that Izanagi withdrew in the north of Japan, in Kyushu Island. Just before he retired he gave his power to his children: Amatarasu became the supreme divinity, his first brother became the sovereign of the night and Susanoo received the sea empire

Izanagi (on the left) and Izanami (on the right) who threw the spear and created Japan

But this last mentioned was jealous and decided to provoke his sister, the sun goddess.

In a first time, Amataresu lose this fight and she was confined in a cavern and consequently, the world was private of sun and harvests were very poor. With the help of other gods, Susanoo was banned from the sky and the sovereignty of the goddess was confirmed. After this, Susanoo came back in the Earth and saved a young girl from

a dragon, found a sword in the monster and gave it to his sister in order to forgive him, like a peace offering. He got married with the young lady and they had many children who are powerful gods. These gods finally succeed in reigning on the world. The greatest of them was Okuninushi, the “Great sovereign of Japan”. Amataresu, worried by this domination of Susanoo’s child, sent his grandson Honinigi in mortal world in order to reestablish her sovereignty. To manage in his mission, it was given to the grandson three talismans: a sacred mirror which had used yet to pushed out Amataresu of her cavern, the sword given by Susanoo which called later Kusanagi and had supernatural powers and finally a jewel of fertility. In accordance with tradition, Honinigi arrived on the mount Takachio, on the island Kyushu and passed an agreement with Okuninushi. In exchange of the faithfulness of this last mentioned, the grandson promised him his grand-other recognized him as the perpetual protector of the imperial family which was founded by the great grandson of Honinigi, Jimmu Tenno who became the first emperor and with this instauration of majestic line, “Age of Gods” ended. Kamis of this time, of the “Age of Gods” were either amatsukamis (celestial kamis, like Amataresu) or

kunitsukamis (land kamis of which Okuninushi belongs). This instauration and the story of the Japan origin have a very important place in Shinto.

Now we are briefly presented origin of Japan and their principal kamis, we will develop the ethic principles of Shinto, what is the base of Shinto, its aims.

Though Shinto has no absolute commandments for its adherents outside of living "a simple and harmonious life with nature and people", there are said to be "Four

Affirmations" of the Shinto spirit:

Tradition and the family: The family is seen as the main mechanism by which traditions are preserved. Their main celebrations relate to birth and marriage.

Love of nature: Nature is sacred; to be in contact with nature is to be close to the kami. Natural objects are worshipped as containing sacred spirits.

Physical cleanliness: Followers of Shinto take baths, wash their hands, and rinse out their mouths often.

"Matsuri": Any festival dedicated to the Kami, of which there are many each year.

The priority accorded to groups and to the solidarity is one of the oldest and one of the most important principles of Shinto. Even though this principle was inherited on the

Chinese culture, it was very reinforced by old Shinto. Indeed, Confucianism and Taoism which came from China said that the absolute lack of social conformism entrains the chaos but this idea was in existence yet. This had only reinforced the Shinto ethic. This ethic was grounded on two fundamental and inseparable concepts: necessity to save his face, keep his honor in front of his family or his friends in every situation and also the concept of a big family which includes ancestors. Moreover, Shinto theology was grounded on an idea of harmony. In Japan, they called it the wa. Every stuff which disturbs this wa is bad. From them, we understand why in Japan the individual person is less important than the group, the family or even the pecking order. Rules which govern human relations were considered as fundamental for the good shape of

wa, without world were in total chaos. This haunting care of wa in

Shinto appeared in many Japanese customs which have been seen like action without any link with the religion too. For instance, the tradition we all know, this fact of take one’s shoes off which every japans respect contributes to harmony in universe. Notions of renovation and purification are also essential in Shinto theology. Each sanctuary has his tank of pure water

(opposite) in order to believers purify them before approach the representation of kami. Believer takes a little of water in a dipper of bamboo which he pours on his hands and rinse out his mouth. In acting like this, he purifies his body inside but outside too and he is suitable for entering in sanctuary in front of gods.

One of the essential differences of Shinto with another religion is that in Shinto, there are no sacred books which underline a moral behavior, like Bible with Christianity or Quran with Islam. However, this religion emphasizes on the notion o purity through, like we developed before, rituals which are specified to splash out bad forces in humans or nature and in order to govern the world with the essential idea of harmony, cohesion.

Shinto teaches that certain deeds create a kind of ritual impurity that one should want cleansed for one's own peace of mind and good fortune, not because impurity is wrong in and of itself. Wrong deeds are called "dirtiness" (kegare), opposed to "purity"

(kiyome). Normal days are called "ke", and festive days are called "sunny", or simply,

"hare”. Killing living beings should be done with reverence for taking a life to continue one's own, and should be kept to a minimum. Modern Japanese continue to place great emphasis on the importance of ritual phrases and greetings (aisatsu). Before eating, many (though not all) Japanese say, "I will humbly receive [this food]" (itadakimasu), in order to show proper thankfulness to the preparer of the meal in particular and more generally to all those living things that lost their lives to make the meal. Failure to show proper respect can be seen as a lack of concern for others, looked down on because it is believed to create problems for all. Those who fail to take into account the feelings of other people and kami will only bring ruin on them. The worst expression of such an attitude is the taking of another's life for personal advancement or enjoyment. Those killed without being shown gratitude for their sacrifice will hold a grudge (urami) and become a powerful and evil kami that seeks revenge (aragami). This same emphasis on the need for cooperation and collaboration can be seen throughout Japanese culture today. Additionally, if anyone is injured on the grounds of a shrine, the area affected must be ritually purified. In relation with this notion of purity, we have to develop the purification which is a vital part of Shinto. This may serve to placate any restive kami, for instance when their shrine had to be relocated. Such ceremonies have also been adapted to modern life. A more personal purification rite is the purification by water.

This may involve standing beneath a waterfall or performing ritual ablutions in a river-mouth or in the sea (misogi). This practice comes from Shinto history, when the kami Izanagi first

performed misogi after returning from the land of Yomi, where he was made impure by

Izanami after her death. A third form of purification is avoidance, that is, the taboo placed on certain persons or acts. To illustrate, women were not allowed to climb Mount

Fuji until 1868, in the era of the Meiji Restoration. Although this aspect has decreased in recent years, religious Japanese will not use an inauspicious word like "cut" at a wedding, nor will they attend a wedding if they have recently been bereaved.

Furthermore, we must distinguish Shinto from pantheism because for it, there is no relation between ethos and substance, for it there is something spiritual in every stuff or humans. In the same way, this belief doesn’t believe in a separation between a divine world and human world. Human being live, evolve in a world in which some supernatural forces step in. So believers pay attention to pray for Kamis who made well and to move away evils, onis. Nevertheless, according to the veritable Shinto, like Japan has a divine origin, all japans have a spiritual essence. So, they had to serve the

Emperor because he is one of the descendants of the sun goddess, Amataresu. This emperor has a mission which is to give to japans prosperity and peace. Consequently,

Japanese life is synonymous of work and until you work, prosperity will come even though there are highs and lows. There is another consequence with the existence of spirituality in every human being. This is the notion of the afterlife, the life after the death. Moreover, because Shinto and Buddhism had co-existed for well over a millennium, these two religions are many mixed in Japanese life. So, for Japanese, there is a life after the death and this idea comes from Buddhism.

So Shinto followers respect four fundamental principles; respect of tradition, familial harmony, respect of nature and research of peace and at last, festivals. These principles follow from the belief which is at the beginning of Shinto: Kamis are spiritual forces with the vocation to guarantee universal harmony.

III) Rituals, practices and shrines

A.

Rituals of Shintoism

Many rituals exists and rhythm the life of the Shinto population. Each ritual implies that people make a party for all the community to celebrate the gods of Shinto.

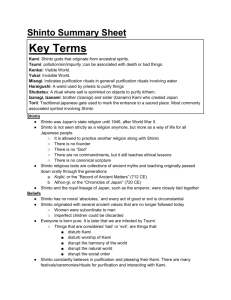

MATSURI

The main celebration in the Shinto is calling « MATSURI »; from MATSU that mean

« the waiting of god coming”. The matsuri has the objective to renew the heavy health that is between human and god. Gods come during the celebration take the body of the actors who play cultural drama from traditional dance. The scenario describes the hopeless in the nature for the next year! This is during 5 parts!

First one: The purification

Second one: God calling

Third one: propitiatory offertories

Forth one: union between god and human

Fifth one: start of god

Purification

Purification rites are a vital part of Shinto.

These may serve to placate any restive kami, for instance when their shrine had to be relocated.

Such ceremonies have also been adapted to modern life. For example, a ceremony was held in 1969 to hallow the Apollo 11 mission to the moon, new buildings made in Japan are frequently blessed by a Shinto priest during the groundbreaking ceremony, and many cars made in Japan have been blessed as part of the assembly process. Moreover, every Japanese car factory built in the United States or away from

Japan has had a groundbreaking ceremony performed by a Shinto priest, with occasionally an annual visitation by the priest to re-purify. A more personal purification rite is the purification by water. This may involve standing beneath a waterfall or performing ritual ablutions in a river-mouth or in the sea (misogi). This practice comes from Shinto history, when the kami Izanagi-no-Mikoto first performed misogi after

returning from the land of Yomi, where he was made impure by Izanami-no-Mikoto after her death. These two forms of purification are often referred to as harae ( 祓 ). A third form of purification is avoidance, that is, the taboo placed on certain persons or acts.

To illustrate, women were not allowed to climb Mount Fuji until 1868, in the era of the

Meiji Restoration. Although this aspect has decreased in recent years, religious

Japanese will not use an inauspicious word like "cut" at a wedding, nor will they attend a wedding if they have recently been bereaved.

Shrines

The principal worship of kami is done at public shrines, although home worship at small private shrines (kamidana) (sometimes only a high shelf with a few ritual objects) is also common. It is also possible to worship objects or people while they are still living. While a few of the public shrines are elaborate structures, most are small buildings in the characteristic Japanese architectural style. Shrines are commonly fronted by a distinctive Japanese gate (torii) made of two uprights and two crossbars. These gates are there as a part of the barrier to separate our living world and the world the kami live in. There are often two guardian animals placed at each side of the gate and they serve to protect the entrance. There are well over 100,000 of these shrines in operation today, each with its retinue of Shinto priests. Shinto priests often wear a ceremonial robe called a joe. Kami are invoked at such important ceremonies as weddings and entry into university.

The kami are commonly petitioned for earthly benefits: a child, a promotion, a happier life. While one may wish for ill fortune on others, this is believed to be possible only if the target has committed wrongs first, or if one is willing to offer one's life. Though

Shinto is popular for these occasions, when it comes to funerals most Japanese turn to

Buddhist ceremonies, since the emphasis in Shinto is on this life and not the next.

Almost all festivals in Japan are hosted by local Shinto shrines and these festivals are open to all those that wish to attend. While these could be said to be religious events,

Japanese do not regard these events as religious since everyone can attend, regardless of personal beliefs.

Ema

In medieval times, wealthy people would donate horses to shrines, especially when making a request of the god of the shrine (for example, when praying for victory in battle). For smaller favors, giving a picture of a horse became a custom, and these are popular today. The visitor to a shrine purchases a wooden tablet with a likeness of a

horse, or nowadays, something else (kanji, an arrow, a snake, or a number of other animals), writes a wish or prayer on the tablet, and hangs it at the shrine. In some cases, if the wish comes true, the person hangs another ema at the shrine in gratitude.

Kagura is the ancient Shinto ritual dance of Shamanic origin. The word "Kagura" is thought to be a contracted form of kami no kura or seat of the kami or the site where the kami is received There is a mythological tale of how Kagura dance came into existence. The sun goddess Amataresu became very upset at her brother so she hid in a cave. All of the other gods and goddesses were concerned and wanted her to come outside. Ame-no-uzeme began to dance and create a noisy commotion in order to entice

Amataresu to come out. The kami (gods) tricked Amataresu by telling her there was a better sun goddess in the heavens. Amataresu came out and light returned to the universe.

Music plays a very important role in the kagura performance. Everything from the setup of the instruments to the most subtle sounds and the arrangement of the music is crucial to encouraging the kami to come down and dance. The songs are used as magical devices to summon the gods and as prayers for blessings. Rhythm patterns of five and seven are common, possibly relating to the Shinto belief of the twelve generations of heavenly and earthly deities. There is also vocal accompaniment called kami uta in which the drummer sings sacred songs to the gods. Often the vocal accompaniment is overshadowed by the drumming and instruments, reinforcing that the vocal aspect of the music is more for incantation rather than aesthetics.

In both ancient Japanese collections, the Nihonshoki and Kojiki, Ame-no-uzeme’s dance is described as asobi, which in old Japanese language means a ceremony that is designed to appease the spirits of the departed, and which was conducted at funeral ceremonies.

Therefore, kagura is a rite of tama shizume, of pacifying the spirits of the departed. In the Heian period (8th-12th centuries) this was one of the important rites at the

Imperial Court and had found its fixed place in the tama shizume festival on the eleventh month. At this festival people sing as accompaniment to the dance: “Depart!

Depart! Be cleansed and go! Be purified and leave!” This rite of purification is also known as chinkon. It was used for securing and strengthening the soul of a dying person.

It was closely related to the ritual of tama furi (shaking the spirit), to call back the departed soul of the dead or to energize a weakened spirit. Spirit pacification and rejuvenation were usually achieved by songs and dances, also called asobi. The ritual of chinkon continued to be performed on the emperors of Japan, thought to be descendents of Amataresu. It is possible that this ritual is connected with the ritual to revive the sun goddess during the low point of the winter solstice.

There is a division between the kagura that is performed at the Imperial palace and the shrines related to it, and the kagura that is performed in the countryside. Folk kagura or kagura from the countryside is divided according to region. The following descriptions relate to Sato kagura, kagura that is from the countryside. The main types are: miko kagura, Ise kagura, Izumo kagura, and shishi kagura.

Miko kagura is the oldest type of kagura and is danced by women in Shinto shrines and during folk festivals. The ancient miko were

Shamanesses, but are now considered priestesses in the service of the Shinto Shrines.

Miko kagura originally was a shamanic trance dance, but later, it became an art and was interpreted as a prayer dance. It is performed in many of the larger Shinto shrines and is characterized by slow, elegant, circular movements, by emphasis on the four directions and by the central use of torimono (objects dancers carry in their hands), especially the fan and bells.

Ise kagura is a collective name for rituals that are based upon the yudate (boiling water rites of Shugendo origin) ritual. It includes miko dances as well as dancing of the torimono type. The kami are believed to be present in the pot of boiling water, so the dancers dip their torimono in the water and sprinkle it in the four directions and on the observers for purification and blessing.

Izumo kagura is centered in the Sada shrine of Izumo, Shimane prefecture. It has two types: torimono ma, unmasked dances that include held objects, and shinno (sacred No), dramatic masked dances based on myths. Izumo kagura appears to be the most popular type of kagura.

Shishi kagura also known as the Shugen-No tradition, uses the dance of a shishi (lion or mountain animal) mask as the image and presence of the deity. It includes the Ise daikagura group and the yamabushi kagura and bangaku groups of the Tohoku area

(Northeastern Japan). Ise daikagura employs a large red Chinese type of lion head which can move its ears. The lion head of the yamabushi kagura schools is black and can click its teeth. Unlike other kagura types in which the kami appear only temporarily, during the shishi kagura the kami is constantly present in the shishi head mask. During the Edo period, the lion dances became showy and acrobatic losing its touch with

spirituality. However, the yamabushi kagura tradition has retained its ritualistic and religious nature.

Originally, the practice of kagura involved authentic possession by the kami invoked. In modern day Japan it appears to be difficult to find authentic ritual possession, called kamigakari, in kagura dance. However, it is common to see choreographed possession in the dances. Actual possession is not taking place but elements of possession such as losing control and high jumps are applied in the dance.

B.

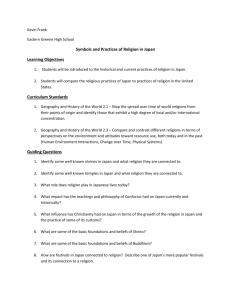

The Shinto’s worship

Shinto worship is highly ritualized, and follows strict conventions of protocol, order and control. It can take place in the home or in shrines. Although all Shinto worship and ritual takes place within the patterns set when the faith was centralized in the 19th century, there is much local diversity.

Worship’ spirit and senses: o In keeping with Shinto values, Shinto ritual should be carried out in a spirit of sincerity, cheerfulness and purity. Shinto ritual is intended to satisfy the senses as well as the minds of those taking part, so the way in which it is carried out is of huge importance. Shinto ceremonies have strong aesthetic elements - the setting and props, the sounds, the dress of the priests, and the language and speech are all intended to please the kami to whom the worship is offered.

Worship’ styles: o

Although Shinto worship features public and shared rituals at local shrines, it can also be a private and individual event, in which a person at a shrine, or in their home prays to particular kami either to obtain something, or to thank the kami for something good that has happened. o

Many Japanese homes contain a place set aside as a shrine, called a kami-dana where they may make offerings of flowers or food, and say prayers. The kamidana is a shelf that contains a tiny replica of the sanctuary of a shrine, and may

also include amulets bought to ensure good luck. A mirror in the centre connects the shelf to the kami. If a family has bought a religious object at a shrine they will lay this on the kami-dana, thus linking home to shrine. o

There is no special day of the week for worship in Shinto because people visit shrines for festivals, for personal spiritual reasons, or to put a particular request to the kami like this might be for good luck in an exam, or protection of a family member, and so on. Worship takes place in shrines built with great understanding of the natural world. The contrast between the human ritual and the natural world underlines the way in which Shinto constructs and reflects human empathy for the universe. The journey that the worshipper makes through the shrine to the sanctuary where the ritual takes place forms part of the worship, and helps the worshipper to move spiritually from the everyday world to a place of holiness and purity. The aesthetics, the ‘look’ of the shrine contributes substantially to the worship, in the way that the setting of a theatre play contributes significantly to the overall drama. Although Shinto rituals appear very ancient, many are actually modern revivals, or even modern inventions.

Worship’s places and theses particularities: o

We can distinguish different places to practice Shinto. A shrine or jinja in

Japanese is a sacred place where kami live, and which show the power and nature of the kami. It's conventional in Japan to refer to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. Every village and town or district in Japan will have its own Shinto shrine, dedicated to the local kami. The Japanese see shrines as both restful places filled with a sense of the sacred, and as the source of their spiritual vitality. They regard them as their spiritual home, and often attend the same shrine regularly throughout their lives. A large shrine can contain several smaller subdivisions of shrines. Shinto shrines can cover several thousand acres, or a few square feet. They are often located in the landscape in such a way as to emphasize their connection to the natural world, and can include sacred groves of trees, and streams. Various symbolic structures, such as torii gates and shimenawa ropes, are used to separate the shrine from the rest of the world.

Some major shrines have a national rather than a local role, and are visited by millions of people from across Japan at major festivals. Visiting a shrine is not the same as going to church, and Japanese people don't visit on a particular day each week. People go to the shrine at festival times, and at other times when

they feel like doing so. Japanese often visit the local shrine when they want the local kami to do them a favor such as good exam results, a good outcome to a surgical operation for a relative, and so on. Many Shinto shrines are places of intense calm with beautiful gardens. The Shinto shrine is a visible and an active expression of the factual kinship which exists between individual man and the whole earth, celestial bodies and deities, whatever name they are given. When entering it, one inevitably becomes more or less conscious of that blood relation, and the realization of it throws into the background all feelings of anxiety, antagonism, loneliness, discouragement. A feeling of almost palpable peace and security falls upon the visitor as he proceeds further into the holy enclosure, and to those unready for it, it comes as a shock. Shrines are made of natural materials whose wood and are designed to provide a home for the particular kami to whom they are dedicated. Although shrines are focus for kami and their devotees. It is very rare for shrines to contain statues of kami. The connection between the shrine and the natural world is emphasized by the way many of the objects within a shrine are made with as little human effort as possible so that their natural origins remain visible. The design of the shrine garden is intended to create a deep sense of the spiritual, and of the harmony between humanity and the natural world. o The entrances to shrines are marked by torii gates, made of wood and painted orange or black. The gates are actually arches with two uprights and two crossbars, and symbolize the boundary between the secular everyday world and the infinite world of the kami. Because there are no actual gates within the torii arch a shrine is always open. There is often no wall or fence associated with the gates. The most spectacular torii are at Fushimi-Inari shrine. o

A shimenawa is a traditional rope made of twisted straw that is often hung between the uprights of a torii. Straws and paper or cloth streamers hang from the shimenawa. A shimenawa can also be used to mark off sacred or ritual areas within the shrine o

These entrances may be guarded by paired statues of dogs or lions, called komainu. Their job is to keep away evil spirits.

o Japanese believe that it is wrong to go near the kami in a state of impurity, so every shrine includes a temizuya or ch ō zuya near the entrance. It is a place for purification with a water trough and ladles for washing hands and face. The route that leads to the shrine buildings is a visual and aural journey that prepares visitors for worship. o The shrine will contain a main hall, a worship hall and an offering hall which may be separate buildings or separate rooms in the same building. The honden is the place where the kami are thought to live. A stick with hanging streamers placed vertically in front of the doors of the honden. It symbolizes the presence of the kami. Only priests are allowed to enter the honden. The offering hall is used for prayers and donations, although people only go into it for special ceremonies.

Routine prayers to the kami are made at the entrance to the hall, where there is a trough in which offerings of money can be thrown and a bell to attract the attention of the kami. o

The presence of the kami is marked by a symbolic object called a shintai. A shintai can be a man-made object and often a mirror. The object itself has sometimes been concealed in wrappings for centuries and so no one knows what it actually is. Natural objects on a larger scale, such as rocks, trees, mountains, waterfalls can also be shintai. o Most shrines are managed by committees made up of priests whose name is

kannushi in Japanese, parishioners and parishioner representatives.

Rituals concerning worships: o Jichinsai are ceremonies held before the construction of a building in Japan, for business or for private. The aim is to purify the ground, worship the local kami and pray for safety during construction.

o The conventional order of events in many Shinto’s worship and festival rituals is as follows:

Purification takes place before the main ceremony

Adoration

Opening of the sanctuary

Presentation of food offerings

Prayers as the prayers’ forms of the 10 th century

Music and dance

Offerings which consist of twigs of a sacred tree bearing of white paper

Removal of offerings

Closing the sanctuary

Final adoration

Sermon

Ceremonial meal which is often reduced to ceremonial sake drinking.