The Uniqueness of the Political Philosophy of Thomas Aquinas

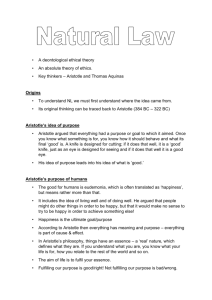

advertisement

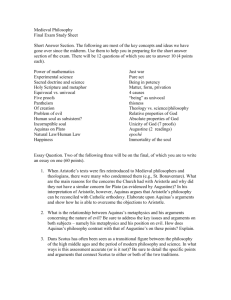

From Perspectives in Political Science, 26 (Spring, 1997), 85-91. -- James V. Schall, S. J. THE UNIQUENESS OF THE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY OF THOMAS AQUINAS "Potestas se habet ad bonum et ad malum. Beatitudo autem est proprium et prefectum hominis bonum. Unde magis posset consistere beatitudo aliqua in bono usu potestatis, qui est per virtutem, quam in ipsa potestate." -- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I-II, 2, 4.1 "Strauss admired the magnificence of Thomas' efforts, and he saw in them a great humanizing and moderating of Catholic theology. Perhaps the greatest gain from the Thomist synthesis was that Aristotle, after being a forbidden author, eventually became a recommended one." -- Harry V. Jaffa, Eulogy of Leo Strauss, November 3, 1973.2 I. To speak of the political philosophy of Thomas Aquinas requires much attention to the nature and scope of what and how he wrote about political things. What is most obviously perplexing to modern readers about Thomas Aquinas is that he did not write a separate book or treatise on politics analogous to what we are used to when we speak of the classics in political philosophy -- Cicero's De Re Publica or Hobbes' Leviathan, for instance. To find out what Aquinas might have said about political things, we must look in what seems, to the contemporary reader, to be in the oddest of places, in a Commentary on St. Matthew's Gospel, or in a piece of advice to the Ruler of Cyprus, or in a doctoral study about a curious compilation by Peter Lombard, or, especially, in an introductory textbook for beginners in theological studies, called, famously, the Summa Theologiae. When someone does manage to find that amazing book, the Summa Theologiae, he discovers a huge work -- three thousand and eighty-nine large, packed pages in the Ottawa Edition.3 But again, politics does not appear in it, except incidently. Law is discussed, but again, compared to the whole corpus relatively briefly, as if to suggest that Aquinas did not think politics particularly important in human affairs. When he did refer to something that surely was political, like power (potestas), what Aquinas wanted to know about it was not how it worked or how it was organized, but whether it was the final definition of our happiness? To this latter question, he thought not. This very fact that something was more important than politics served to lessen the claims of politics by reducing it to its own sphere. When Aquinas did talk about power (potentia) more often and more at length, he spoke of the power of God (De Divina Potentia, I, 25). Interestingly enough, through Occam, Bodin, and Hobbes, it is this "omnipotence" or divine power that eventually wound its way into political philosophy in a manner that ended by divinizing the state at the expense of both God's power and civil 1 "Power relates itself to both good and evil. Happiness, however, is the proper and perfect good of man. Hence, any happiness would more consist in the good use of power, which is by way of virtue, than in the power itself." (Translations, unless otherwise indicated, are of the author). 2 Harry V. Jaffa, "Leo Strauss: 1899-1973," (Eulogy delivered at Bridges Chapel, Claremont, California, November 3, 1973), The Conditions of Freedom (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975), p. 6. 3 A brief bibliography of Thomas Aquinas might be useful: Josef Pieper, Guide to Thomas Aquinas (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1986); Peter Kreeft, A Summa of the Summa (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990); James A. Weisheipl, Friar Thomas D'Aquino (Washington, D. C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1983); Brian Davies, The Thought of Thomas Aquinas (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993); G. K. Chesterton, St. Thomas Aquinas (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday Image, 1956); Jean-Pierre Torrell, St. Thomas Aquinas, Translated by Robert Royal (Washington, D. C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1996); Charles N. R. McCoy, "St. Thomas and Political Science," On the Intelligibility of Political Philosophy: Essays of Charles N. R. McCoy (Washington: The Catholic University of America Press, 1989), pp. 24-38; Ernest Fortin, "St. Thomas Aquinas," History of Political Philosophy, Edited by Leo Strauss and Joseph Cropsey (Third Edition; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), pp. 248-75; James V. Schall, "Political Philosophy: Remarks on Its Relation to Metaphysics and Theology," Angelicum, Rome, LXX (1993), 487-503. 1 freedom. The history of political philosophy is directly related to the history of theology, once the limits of each are questioned. Aquinas observed, to briefly explain his position, that legitimate political power as such needed the discipline of reason and virtue before its use could be designated as good or bad. Power, thus, was presupposed to something else before we could properly begin to think about it or act with it. What does appear in the Summa Theologiae, however, is "law", for the accomplishment of which law, political authority with coercion can be required. But Aquinas' discussion of law is not quite like anything ever found listed under law in the legal casebooks, though natural law is not wholly unknown, while civil or human positive law is something we live under every day. Indeed, and this is also a question relative to Aquinas' discussion of law, we seem to live under nothing else but human positive law, itself unrelated to any "higher law". Aquinas' famous definition of law -- quaedam rationis ordinatio ad bonum commune, ab eo qui curam communitatis habet, promulgata (I-II, 90, 4) -- already contains within it the purpose of the civil society, the essence or purpose of its enactments, who does the enactment and finally to whom the law is addressed. 4 In a very basic sense, any political disorder will arise from a violation of one or other of these principles. It is to be noticed that Aquinas does not list "coercion" as an attribute of the essence of the state, though he did not propose that it was never necessary. He merely hinted that it was only necessary in a polity wherein one or other of these essential elements was not functioning properly. Thomas did deal with a subject related to both power and law, namely, justice. The object of justice, he tells us, is jus or right. The proper and improper understandings of this jus in the form of "rights" theory have constituted much of the political theory of modernity. From another angle, this same jus, what it is that justice restores or relates, is the object of law, not some autonomous internal quality called "natural right" with no further reference to anything but the will that proposes it. Aquinas deals with justice in a more detailed fashion in many of his works, including the Summa Theologiae (II-II, 57-61). For Aquinas, justice, the right relation to others, the returning to them their due, the habitual disposition that we ever seek this "rightness" in whatever we do in the world of other human beings, does not seem to be as important as prudence, the intellectual moral virtue (II-II, 47-56). It is prudence, not justice, after all, that tells us specifically what we are to do in each case, after having taken into consideration all the circumstances and particulars of the case. Prudence is what puts the stamp of precisely our intellect on each action that proceeds out of us, including the acts of justice, so the act can be identified as our act. Once we know what is the right thing to do through prudence and the metaphysics on which it rests, we can be just. That is, we can actually do what is objectively just or right because we see that it is just and we choose to do it for this and no other reason. However, justice appears to run into many curious difficulties. In Aristotle, and also in St. Thomas, friendship is more important than justice, even in the city, especially in the city. The fact is that when Aquinas comes to discuss the highest of the Christian virtues, charity, he bases his discussion on friendship (amicitia), not on justice. This choice of Aquinas may be the most important selection in all of social philosophy both by way of confirmation of Aristotle and by way of emphasizing something beyond him. Unlike justice, which looks to the abstract relationship between persons in terms of what is due or not due, not to the persons themselves, friendship and charity look primarily to the person who is the object of our friendship or love. This emphasis on friendship may be one of the most consoling and striking teachings in all of Aristotle or Aquinas. 5 II When it comes to the discussion of creation, furthermore, Aquinas will say that the world was not made in justice but in mercy (I, 21, 4). In creating from nothing, God did not "owe" anything to anyone in justice, in particular He did not "owe" them their very existence. Once created, He owed them, as it were, what they are, so 4 "Law is a certain ordination of reason for the common good from the legitimate authority and promulgated." 5 See James V. Schall, "Friendship in Aristotle," The Classical Bulletin, 65 (#3-4, 1989), 63-68. 2 that there is a kind of consequent justice in creation, all of which is presupposed to the divine mercy. But if existence is not due in justice, it must be due to something higher than, beyond justice. Aquinas' world is filled with something always more than itself, with a kind of abundance more like a gift than like something due in justice. The problem of the world is not that it reveals a kind of niggardly justice or subsistence but that it reveals a kind of unlimited superabundance. The mystery is "why is there so much, not why is there so little?" This awareness of the gift nature of reality also seems to suggest a further emphasis in Aquinas. God has an internal life that seems itself societal or containing within it an otherness. Aquinas' "thought thinking itself" takes on a richness that does not necessarily disagree with Aristotle but makes him more coherent in his own order. Moreover, we find a great emphasis on love and forgiveness in Aquinas. He seems to take the Aristotelian virtue of epichia or equity, which is an aspect of justice that covers those instances in which justice does not seem to work, more seriously. He sees the whole discussion of justice in need of something more than itself. Justice when it is complete seems at that very moment most tantalizingly incomplete -- which may help to explain why so many modern justice theories, including those that are religiously based, have ended unexpectedly in ideology and coercion. Since in a sense, justice leads to friendship, which in turn seems to expect something beyond itself, charity, in fact, those intellectual systems closed to revelation have the greatest of temptations to supply by themselves those exalted expectations that are still alive in the tradition from revelation. It would not exactly be correct to say, in comparison to Aristotle, that Aquinas downplays justice, the obvious political virtue, for he gives it its due. He thinks about it, defines it, examines it, locates it among the other virtues and activities of the human and divine reality. We can even speak of the justice of God (I, 21, 1-2). But he does not think that the human reality can ever be fully assumed under the virtue of justice, which does not direct itself to persons but to relationships. Again, justice has a place and a proper place in the order of things, but, like politics, it is not the highest place. For Aquinas, justice is the virtue of making things right within and among all beings, including human beings. Law looks to establish this same rightness but from the point of view of some authority looking at human relations to try to clarify, when it can, what exactly this justice is and to enforce its violations when they unsettle others in civil society. St. Thomas, in addition to "natural law", talked about "eternal law", "divine law", "human law", even a "law" of sin (lex fomitis). He was very precise and explained how each of these kinds of law related to each other and to their origin or basis (I-II, 90-108). Moreover, the discussion on law appeared in a precise intellectual place, almost as if there were a proper order of reason according to which we should discuss each particular intellectual and existential issue. In fact, one of the unique features of the Summa Theologiae is precisely that, namely, the way it locates the subject of discourse, to know what we are talking about and why we are talking about it in a certain manner in relation to other discussions. Law was what Aquinas called an "external principle of action", to be distinguished both from internal principles of reasoning and from internal principles of action, such as intellect, will, passions, and habits. The modern mind will be confused on learning that the "external" principles of action are God, the devil, and law. By an external principle of action, Aquinas does not primarily mean potestas in the sense of coercion, even though it may come to be used legitimately, as he explains in his discussion of the state authority confronting irrational acts that are harmful to others. An external principle is action means primarily some rule or norm of action, known and objective in the sense that it is understood by the one acting to have been set down by the lawgivers in a proper fashion -- Speed Limit, 25 MPH. An external action in the sense of a good law, moreover, is not a violation of reason or nature, but in fact what is required by reason and nature; it is either a making clear what is already known to be good or bad, or it is designating some particular aspect of its being carried out that could allow alternative ways, but from among which one must be chosen -- drive right, not left. A known law indicates to us the elements that we must take into consideration before and as we act. A law as such is not external as if it were not spiritual or intellectual. The law is a product of intellect (of the legitimate lawgiver) addressed to intellect (of the citizen who is to obey it). The one subject to the law is to know it. But he also knows that he did not make the law, which gains its force by virtue of the legitimacy of the lawgiver and the rightness and purpose of the proposed norm. 3 So the observance of a law that is understood and known to be fair and just is not an alienation of intellect, but its perfection. To observe an understood and fair law is not to be coerced by it. Coercion only arises for Aquinas when someone acts unreasonably in a situation that seriously endangers others or the common good. Thus, a free and just society will be one primarily run by free obedience to law on the part of those who understand and will to be just or fair according to its stipulations. A society that requires a constant and heavy dose of coercion is one rapidly deviating from the norms of reason and free adhesion to what is understood to be required. III. Aquinas also, as Harry Jaffa remarked, commented on Aristotle. Aquinas wrote an explication, a very orderly and detailed account, of the texts of the Metaphysics, the Physics, the Ethics, and the early part of the Politics, in addition to a number of other of Aristotle's works such as his logical works. Why is this important? Why not just read Aristotle? The answer is twofold. Aquinas' commentaries and readings of the Aristotelian texts point out and resolve many of the ambiguities that were thought to be found in Aristotle. He reasoned out many of the ideas that Aristotle was not certain about, though Aquinas thought that, even when Aristotle suggested a wrong conclusion or direction, it was always a possible and plausible argument. The light of revelation made the brilliance of Aristotle seem more, not less, luminous. When Aquinas presumed to present exactly what Aristotle said, he also resolved and elaborated his own position within the tradition that reads Aristotle as part of the exercise of seeking the truth, including the truth of revelation. If Aquinas can see Aristotle's argument in a more complete way, or resolve some textual or intellectual confusions, he will do so. In this sense, Aquinas was not merely providing another way to read Aristotle, but a way to think with Aristotle and beyond him. The basic reason why Aquinas is important is not that he saved the texts of Aristotle, though this preservation was a great service, but that he saw the truth in Aristotle in a more coherent way, a way that scrupulously respected Aristotle's text both as to what it said and as to what his argument meant in its fullness. Aquinas was not a slave to Aristotle; both Aristotle and Aquinas were concerned about the truth as such. The second reason why reading Aquinas is not merely reading a better edition of Aristotle is because Aquinas is saying that Aristotle is the primary authority or text on ethical and political things. This is not merely a judgement about Aquinas commenting on Aristotle in comparison to Plato or to the Stoics, but it also relates to revelation. Aquinas indicated, implicitly, that politics, the highest of the natural practical sciences, is not the purpose of revelation. We do not go to the Bible for our initial or primary understanding of political things. Revelation had a profound effect on political things, no doubt, but it does is not intended to replace our natural understanding of politics and the experiential way we come to know how politics deals with the right and wrong order of our souls. Revelation is addressed to certain questions and issues that arise in reason, including political or practical reason deliberating on the right order of common political life. Without an authentic political philosophy, we could not know whether or why revelation was addressed to us in the first place or why it would make sense to pay attention to it.6 Revelation in this sense presupposes nature, to follow a famous principle of Aquinas. One of the main problems of modern theology, paradoxically, will be caused by its lack of a sound political philosophy, the lack of which leads it easily into the utopianism or pragmatism found in modern political philosophy. Similarly, one of the abiding problems in modern political philosophy will be, the ignoring or rejecting the authentic eagerness of man to know what he and his world is about. Modern philosophy, including political philosophy, will choose to close itself off from even considering the possibility that revelation is addressed to genuine political philosophy in terms precisely of its own reason. Aquinas stands for the position that this closing off is a "choice", not a philosophic truth or necessity. IV. 6 This point is argued further in my Reason, Revelation, and the Foundations of Political Philosophy (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987) and At the Limits of Political Philosophy: From "Brilliant Errors" to Things of Uncommon Importance (Washington: The Catholic University of America Press, 1996). 4 If we are to address ourselves to the "uniqueness" of the political philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, then, we must constantly be aware that to understand political things, we need to know more than political things. Aristotle, in an oft quoted passage, said that if man were the highest being, politics would be the highest science (1141a20-22; see 987b20-27). This statement is not designed to lessen man's importance but to identify the practical science of politics in its proper place. It suggests that there is a relation between the truth of man and the freedom of man. There is a wisdom higher than the practical wisdom, or prudence, that is politics, both in the sense of metaphysics and in the sense of revelation. The explicit or implicit denial of this higher wisdom alone can make it tempting to elevate politics, already a high science in its own practical realm, into the highest science simply. To accomplish this elevation, the theoretical sciences of what is, of being, have to become subordinate to politics, so that there is no criterion of reality able to resist the judgement of the politician. This is the reason why death and political philosophy are intimately related as we recall in the trials of Socrates and Christ in which the state, with its power over life and death, seeks to use this power as an instrument of truth defined solely by the polity. 7 The deaths of Socrates and Christ graphically indicate the limits of politics. Aquinas' commentary on this important passage in Aristotle about politics not being the highest science is worth devoting some attention to. It recalls, among other things, the famous common-sensical opinion, found initially in Plato, of the uselessness of the philosopher, namely, the seemingly justified lamenting of a old lady who sees Thales, the philosopher, fall into a pit because he was intent on discussing the stars. First, St. Thomas states the terms of the issue: Inconveniens est si quis politicam vel prudentiam existimet esse scientiam studioissimam, idest optimam inter sciencias. Quod quidem esse non potest nisi homo esset optimum eorum quae sunt in mundo. Scientiarum enim una melior est et honoribilior altra, ex eo quod est melioriorum et honoribiliorum.... Hoc autem est falsum, quod homo sit optimum horum quae sunt in mundo: nec politica, seu prudentia, quae sunt circa res humanas, sunt optimam inter scientias. 8 The highest sciences depend on what are in fact the highest things. Since human things, both in individual life and in the polity, concerns changeable human things, the study of these things, a legitimate study in itself, cannot be the highest study. Notice that for Aquinas this denial that politics is the "science most worthy of study" is not a belittling of human things except over against those theories that maintain that man is the highest being This latter question about what is in fact the highest thing is not to be resolved by politics but by metaphysics, the study of what is. In showing that prudence is subject to philosophic wisdom, Aquinas recalls that Anaxagoras and Thales were considered to be wise men but not prudent men. This story is told to "reprehend" the philosophers, though by implication Aquinas does not think that either Thales or Anaxagoras are particularly reprehensible. 7 See James V. Schall, "The Death of Plato," The American Scholar, 65 (Summer, 1996), 401-15; At the Limits of Political Philosophy, ibid., Chapter 6, "Dwellers in an Unfortified City: Death and Political Philosophy," pp. 103-22, and Chapter 7, "The Death of Christ and the Death of Socrates," pp. 123-44. 8 "It is not fitting that we think that some politics or prudence be the highest science, that is, the highest among the sciences. This could not be the case unless man were the best of those things that are in the world. Of the sciences, one is better and honorable than an other from the fact that it is a science about better and more noble things.... It is however false that man is the best of those things that are in the world: therefore neither politics nor prudence, which are about human things, are the best of the sciences." Thomas Aquinas, In Decem Libros Ethicorum Aristotelis ad Nicomachum Expositio (Italy: Marietti, 1964), L. VI, l. vi, #1186, pp. 325-26. 5 Cum enim Thales exivit domum, un astra consideraret, incidit in foveam; eoque lugente, dixit ad eum quaedam vetula: Tu quidem, o Thales, quae ante pedes sunt nequis videre, ea quae in coelo sunt, putas cognoscere? Anaxagoras autem cum nobilis et dives esset, paterna bona suis dereliquit, et speculationi naturalem se dedit, non curans de politica, unde ut negligens reprehendebatur. Respondit: Mihi patria valde curae est, ostenso coelo. 9 These famous and charming stories are recalled, it is to be noted, not to agree, but to disagree that politics or worldly affairs are the most important things. That is, even when the philosopher does what to most people appear to be silly and impractical things, like falling in a pit because he is too eagerly discussing the higher things, his vocation still remains to seek wisdom, which is not about human affairs. Neither Plato nor Aquinas were advocating that philosophers be so absent-minded as constantly to be falling into holes while pursuing their trade. Rather they were reminding us of the intrinsic charm and fascination of those things that were divine, even granting the interest in the political life and the need of the economic life for sustenance. The people who laugh and ridicule the philosopher are in the unfortunate position of not yet being struck by the fascination that exists beyond merely human affairs, to which, though important in themselves, we are not to devote all our time. V. Aquinas, in his commentary on Aristotle's Ethics, took up this same theme later in Book X in a more detailed fashion. Indeed, Aristotle's remarks on speculative and political happiness, as well as on the curious nature of his transition to the Politics in this book, along with Aquinas' reflections on them, show just why Aquinas is unique in political philosophy. Aquinas does not have any major quarrel with Aristotle on this score. 9 "For when Thales left his house in order to consider the stars, he fell into a ditch; bewailing on seeing this, a certain old woman said to him, "You indeed, O Thales, since those things before your very feed you cannot see, what things in heaven do you think to know?" Anaxagoras, however, when he was rich and noble, left his paternal goods and dedicated himself to the speculation of natural things, not caring about political things, hence was reprehended as negligent, and said to him, "do you have no care of your fatherland?" He answered, "My fatherland is of great concern to me, I contemplate the heavens." Ibid., #1192, p. 326. The philosopher's true father land, in other words, is not his native land but the cosmos. We have already here intimations of the Stoic idea of the brotherhood of all man and of Augustine's City of God. 6 ... Cum felicitas sit operation secundum virtutem..., rationabiliter sequitur, quod est operatio secunum virtutem optimam.... Felicitas est optimum inter omnia bona humana, cum sit omnium finis. Et quia melioris potentiae melior est operatio, ... consequens est quod operatio optima hominis sit operatio eius, quod est in homine optimum. Et hoc quidem secundum rei veritatem est intellectus. 10 After again examining all the candidates for human happiness, including the careful examination of pleasure in Book X, Aquinas concludes with Aristotle that the location of happiness is in fact in the highest or intellectual activity of a human person in so far as that person is seeking the highest object of intellect in its very activity -- an activity that has a proper object. This is the importance of the story of the philosopher whose homeland is in the heavens and in their fascination to him. Aquinas again examines the purity and nature of the operation of the intellect. "Inter omnes operationes virtutis delectabilissima est contemplatio sapientiae, sicut est manifestum et concessum ab omnibus."11 Aquinas appeals here both to experience and to evidence, but again he is in part establishing a happiness to which any political happiness, which he will treat shortly, is related, if indirectly. Aquinas recognizes the need of material goods and of the moral virtues.12 But the moral virtues are seen to need other people by some intrinsic necessity of themselves, something that makes them less exalted than the speculative virtues. However, in developing this, to us, strange position of Aristotle about the self-sufficiency (αυταρκια) of the wise philosopher who needs very little in the way of material goods, Aquinas connects this contemplative freedom with Aristotle's treatise on friendship and with his own notion that the highest form of life is not simply to contemplate, but to teach what is contemplated (contemplata tradere). Quia contemplatio veritatis est operatio penitus intrinsica ad exterius non procedens. Et tanto aliquis magis poterit solus existens speculari veritatem, quanto fuerit magis perfectus in sapientia. Quia talis plura cognoscit, et minus indiget ab aliis instrui aut juvari. Nec hoc dicitur quia contemplationem non juvet societas; quia ut in octavo dictum est (the treatise on friendship), duo simul viventes intelligere et agere magis possunt. Et ideo subdit, melius esse sapienti, quod habeat cooperatores circa considerationem veritatis, quia interdum unus videt quod alteri, licet sapientiori, non occurrit.... 10 "Since happiness is an operation according to virtue, it reasonably follows, that it is the operation following the very best virtue. Happiness is the best among all human goods, since it is the end of all. And since the better operation is of the better potency, it follows that the very highest operation in man is the operation of this power, which is the highest in man. And this, according to the truth of reality is the intellect." Ibid., #2080, L. X, l., x, p. 542. 11 "Among all the operations of virtue, the most delightful is the contemplation of wisdom, as is manifest to and granted by all." Ibid., #2090, L. X, l. x, p. 543. 12 Ibid., #2092-93, pp. 543-44. 7 Nihil enim accrescit ex contemplatione veritatis praeter ipsam veritatis speculationem. Sed in exterioribus operationibus semper homo acquirit aliquid praeter ipsum operationem, aut plus aut minus; puta honorem aut gratiam apud alios quae non acquirit sapiens ex sua contemplatione, nisi per accidens, in quantum scilicit veritatem contemplatam aliis enunciat, quod jam pertinet ad exteriorem actionem. 13 Aquinas makes the point here that the truth is in fact what fascinates us and which we want to possess for ourselves. Even in the case of friends, their aid to one another and their teaching of one another is in the line of the possession of truth. In Aquinas' appreciation of this central truth of Aristotle's whole ethical treatise, it is precisely the further elaboration of what is truth and what is friendship as seen in revelation that he understands as the completion of Aristotle's analysis. But in the commentary on the Ethics at this point, what concerns Aquinas, as it did Aristotle, is the purpose of what is called political happiness, the more properly human happiness insofar as it deals with what is to be done in this life. Manifestum est in actionibus politicis, quod non est in eis vacatio; sed praeter ipsam conversationem civilem vult homo acquirere aliquid aliud, puta potentatus et honores vel quia in eis non est ultimus finis..., magis est decens, quod per civilem conversationem aliquis vult acquirere felicitatem sibiipsi et cuilibet, ita quod huiusmodi felicitas, quam intendit aliquis acquirere per politicam vitam, sit altera ab ipsa vita politica. Sic enim per vitam politicam, querimus eam quasi alteram existentem ab ipsa. Haec est enim felicitas speculativa, ad quam tota vita politica videtur ordinata.... 14 The example that Aquinas used immediately following the above passage was that of war and peace, to recall that the purpose of action or war is peace or leisure. The constant teaching of Aquinas here is that, however important the political life, it is not happiness and its own order, being something valuable in itself, nevertheless is ordered to making the highest activities in man possible in each and every person. VI. In what is perhaps an indirect commentary on the judgment about the relation of Aristotle and Aquinas made at the funeral of Leo Strauss by Harry Jaffa, namely, that Aquinas is mainly important because he kept alive the work of Aristotle in the West and passed it on to us, Ernest Fortin made the following remarks in his own evaluation of Aquinas: 13 "The contemplation of the truth is an interior operation not proceeding to the exterior. And this the more someone is able to exist alone in speculating the truth, the more he will be perfect in wisdom. Because as such a one knows more things, the less he needs to be instructed and helped by others.... "We do not imply that society does not help contemplation, since as we said in the Eight Book, two persons simultaneously living together are better able to think and act. And therefore, he (Aristotle) adds, that it is better to be a wise man who has cooperators in the consideration of the truth, since sometimes one sees what it does not occur to the other, even though he be wiser.... "... For nothing accrues to a man from the contemplation of the truth except the speculation of truth itself. But from exterior operations, man always acquires something exterior to himself, for example, honor or benefit from others, which the wise man does not acquire from his contemplation, except accidentally, namely insofar as he teaches the contemplated truth to others, which teaching is an external act." Ibid., #2095-97, p. 544. 14 "It is clear in political actions that there is not leisure in them; but beyond this very civil conversation, man wishes to acquire something else, for instance, power and honors or because in them is not found the ultimate end.... It is more fitting that someone wishes to acquire happiness by civil interchange for himself or someone else, so that the sort of happiness that one wishes to acquire by means of political life may be other than the political life itself. Thus, through the political life we seek that other life existing from it. This is speculative happiness, to which the whole of political life seems to be ordered." Ibid., #2101, p. 546. 8 Contrary to what has often been said, Aquinas did not baptize Aristotle. If anything, he declared invalid the baptism conferred upon him by his early commentators and denied him admission to full citizenship in the City of God. Instead, by casting his philosophy in the role of a handmaid, he made him a slave or servant of that City. In the light of Aquinas' own moral principles, the treatment was not unjust since, in return for contributing to Christian theology, Aristotle received, if not the gift of grace, at least the grace to live. The proof is that, whereas he was eventually banished from Islam and Judaism, he found a permanent home in the Christian West. The place of honor that he came to occupy in the Christian tradition as the representative par excellence of the most glorious achievements of natural reason bears eloquent witness to the novelty and daring of Aquinas' enterprise. 15 Notice that Fortin praises not Aristotle but Aquinas. He praises Aquinas for recognizing Aristotle's philosophical achievements. Again, why praise Aquinas and not Aristotle? Of course, Aristotle is being praised essentially for being right, a rightness that is recognized from the higher viewpoint of the rightness of revelation. The consistency of the whole is what Aquinas saw and explained. Fortin's point, then, is not that it is too bad that no one, not even Aquinas, could, as it were, baptize Aristotle. It is rather that in representing the highest traditions and insights of reason, Aquinas saw in Aristotle a body of truth and method that made it possible to understand more fully what revelation was about in human terms. The importance of Aristotle in his "permanent home," as Fortin called it, is that the avenue of reason remained open both to revelation and to philosophy and science in terms that required each, at the cost of its very intellectual integrity, to account for the other in terms that did not, as they could not, contradict each other. 15 Ernest L. Fortin, "St. Thomas Aquinas," History of Political Philosophy, Edited by Leo Strauss and Joseph Cropsey (Third Edition; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), p. 271. 9 Philosophy, we should recall, does not stand outside of human thought but it itself is human thought seeking to know from the inside ("penitus"), what it is and what it knows. The whole of the political life is itself ordained, albeit in an indirect way, to the happiness found in contemplation ("felicitas speculativa, ad quam tota vita politica videtur ordinata"). Thus, that curious seeking that characterizes the philosopher, even when he falls into his famous pit, itself betrays many perplexities and uncertainties at its best. The happiness is not in the seeking, but in the having found and the continued rejoicing in the truth, as Aquinas remarked in his comments on Aristotle. Revelation comes to the philosopher not by faith but, as it were, by philosophy. It comes to philosophy when it is honestly open not just to itself and what is lower than itself, but to whatever happens and to what is. Revelation only appears to the philosopher when the philosopher has put politics in its proper place and he is left with the proper leisure to wonder about what he has yet to know. This is why we are warned not to get lost in merely human things, because there is something divine in the human intellect and to this all else is ordered. Homo debet intendere ad immortalitatem quantum potest, et secundum totum posse suum facere ad hoc quod vivat secundum intellectum, qui est optimum eorum quae sunt in homine, qui quiden est immortalis et divinus. Quamvis enim hoc optimun sit parvum mole, quia est incorporeum et simplicissimum, et per consequens caret magnitudine molis, tamen quantitate virtutis e pretiositatis multum excedit omnia quae in homine sunt. 16 This passage, perhaps more than any other, spells out the reason why man transcends the city and locates the highest things to which, through the moral virtues, man is oriented. Aquinas' uniqueness arises precisely here, in his systematic responding to the positions and queries of Aristotle reflected upon by Aquinas himself and restated in the clearest of philosophic terms. When this philosophic contemplation is the center of our reflection, we find, as Aquinas remarked, that we are not at all surprised that the political life leads to considerations of the happy life, the solitary life of reason, consulting with others yes, but still in awe at what it knows of what is. It is precisely this highest life that is addressed in revelation in terms that both justify the speculative enterprise itself as having a transcendent object and that correct that strange feeling we have that even the highest life should be "with others", as Aristotle himself knew in his discussion of friendship. We need not be overly surprised, then, that the highest life will come to be described not in terms of solitary contemplation but in terms of the City of God. It is no accident that Aquinas found the best and clearest way to describe what the love of God and of others in God might mean was to base his discussion of caritas on Aristotle's amicitia (II-II, 23, 1). Thus the Ethics, the Politics, and the Metaphysics are all necessary to establish the proper questions to which revelation addresses itself as coherent answers, answers that will not be recognized as answers without the hard philosophic work of knowing what we can know of the human and the divine things by our own philosophic efforts. The best guide for these efforts still remains, as St. Thomas thought, Aristotle. "The history of political philosophy since St. Thomas' time," Charles N. R. McCoy wrote, has been a history of successive failures to relate ethics to politics and of successive attempts to find a substitute for theology -- either in politics itself, as fascism does, or in economics as Marxism does. Men are today oppressed by false theologies erected into political systems, and those who are not so oppressed are in risk of becoming so oppressed by an intellectual and moral inability to defend themselves. St. Thomas' political science will not give us the answers to 16 "Man should incline to immortality in so far as he can, and according to his whole capacity to live according to his intellect, which is the highest of those things which are in man, who indeed is immortal and divine. Although this highest element is small in size because it is incorporeal and most simple, and consequently lacks magnitude, nevertheless it exceeds very much, by the quantity of its power and preciousness, all those things which are in man." Aquinas, ibid., L. X., l. xi, #2107, pp. 546-47. 10 problems of hydro-electric development or technological unemployment; but it will give us the answer to the most vital of contemporary problems: how to secure the rational foundations of human living.17 In one sense, the "intellectual and moral ability to defend" ourselves from "false theologies erected into political systems" is the reverse side of the delight in the contemplation of the truth itself. And the opposition that truth finds in the world is itself something that can be wondered about in reason. This opposition also finds its further explication in revelation and in the mysteries of the Fall and evil. The rational foundations of human living, once known, need to be pursued. That is, human living in all its forms, including its political forms, is to be identified according to that order that seems best by nature. St. Thomas provides a consistent way to examine these moral foundations, one of which is the nature and place of politics in human affairs. That it is a human affair is the most important thing to know about politics. It is the highest of the practical sciences, but it is not happiness as such, though both Aquinas and Aristotle call it a kind of secondary yet real happiness. The understanding of political things is, in a sense, to limit them, limit them to what they are and can do. Properly to understand politics, we need to know what politics is not, what it cannot do. What it cannot do is become a metaphysics. It cannot itself become a way of deciding on its own powers. The power of a political prudence cut off from wisdom cannot know what reality, including human reality, is about. The possibility of "human conversation", as Aquinas put it, is that highest reach to which the order of the city is oriented. Once the political task is accomplished, itself a rare and unusual thing, the great human task, the task of wisdom remains. It remains, in fact, even in the worst regime because each human being is directly related to the highest things. The political philosophy of Thomas Aquinas knows the importance of political things because it deals so much more thoroughly and profoundly with those things that are not political. When political philosophy is the only "metaphysics", then we can be sure that the most important human things are simply not known except by those few still willing to seek, even in the most disordered of societies, the highest things, which are not political. This too is the teaching of Thomas Aquinas about the things that are not Caesar's, to recall a phrase from the Gospel of Matthew, a text that Aquinas also found time to consider in his some twenty-five years of active intellectual work. Thomas did not simply preserve Aristotle or Matthew, but he showed that they both belonged to the same man to consider their respective meanings and relationship to each other. 17 Charles N. R. McCoy, "St. Thomas and Political Science," On the Intelligibility of Political Philosophy: Essays of Charles N. R. McCoy, Edited by James V. Schall and John J. Schrems (Washington, D. C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1989), p. 38. 11