this article - Disability Ministries

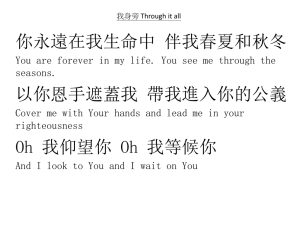

advertisement

Hymns for Disability Awareness Glory to God, and praise and love, be ever, ever given, by saints below and saints above, the church in earth and heaven. So begins the hymn “O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing” by Charles Wesley, traditionally the first in Methodist hymnals. It is a spiritual autobiography, and, as with all of his hymns, includes Wesleyan principles. The hymn also points to questions and concerns for a Disability Awareness Sunday. Too often, hymns are chosen as if the theology expressed by their words does not matter. John Wesley was well aware that hymns form one's theology, and enjoined his followers to sing with spirit and understanding. But time and time again, congregations are asked to join in Augustus Toplady’s anti-Methodist “Rock of Ages” (#361). It would seem that we ought to sing hymns that follow Wesley in proclaiming that grace is available to all. This is one reason why we reach out to all persons, and especially those with a disability, even if they seem to be unable to understand or reply. Many hymns reinforce acceptance of casually-held ideas on the nature of disability, healing, or wholeness, instead of challenging us. For Disability Awareness Sundays, as well as for general use, the challenge to grow into perfect love ought to include singing about acceptance and equality before God. This can create problems—or, as we prefer to think of them, opportunities for teaching. Hymns may include language that makes an analogy of sin to physical, sensory, or other impairments. Others may use such terms to describe spiritual conditions. However, as language and culture change, modern readers may not grasp the use of figures of speech in the way the authors did, especially as history increasingly separates us from their circumstances. “Be Thou My Vision” is the petition of another hymn, and asking for divine guidance as we move toward perfection is a good idea. While some hymns might need to be avoided, most present an opportunity for teaching, preaching, and open discussion about such topics as social power, hope, hurt, exclusion, and inclusion. Therefore we list many hymns, and for several we include notes about their strengths and concerns as a way of raising awareness and opening the way to sharing. This list is not intended to be exhaustive. Most of these hymns do not specifically refer to disability, but they do refer to themes that are important in the context of disability awareness. Suggestions for hymns to be included in this list are welcome, please use the contact page. United Methodist Hymnal #58: “O For a Thousand Tongues To Sing”: abridgment of Charles Wesley's poetic autobiography; the eschatological images of healing—for example, ”leap ye lame for joy”--are painful to some who have been subjected to “healing” statements, even as they are a sign of hope to others. #89 “Joyful Joyful, We Adore Thee”: an inclusive hymn, with a joyful tune from Ludwig van Beethoven's 9th symphony, written when he was totally Deaf. #111 “How Can We Name a Love": seeks wider, modern expressions of God's inclusiveness. #114 “Many Gifts, One Spirit”: could be used as the springboard to deal with including the gifts of all, whatever they are, even those we may not always think of as gifts. #140 “Great is Thy Faithfulness”: although there is nothing specific about disability, this hymn reminds us of God’s presence at all times, and, from its scriptural allusions, especially to those who have lost hope. #178 “Hope of the World”: refers to Christ as compassionate, and calls for return of loving mercy to all. #183 “Jesu, Thy Boundless Love to Me”: Often neglected, as it is published without a tune, this work also reflects on hope, the value of love, and the reality that lies beyond physical, sensory perception. #261 “Lord of the Dance”: refers to the stories of Jesus healing on the sabbath, and responds “the holy people said it was a shame.” This is a reminder that disability awareness work is often counter-cultural, even in the religious sphere, where the healing and restorative works of Jesus were often the subject of controversy. #262 “Heal Me, Hands of Jesus”: the sequence in this hymn is healing and then cleansing. Depending on the context, this may require attention in a preface or sermon. Healing and a physical (or mental) cure are not always the same. #263 “When Jesus the Healer Passed Through Galilee”: this hymn also seems to equate healing with cure, and contains no links to wider concerns of inviting people with disabilities into an inclusive community. #264 “Silence, Frenzied, Unclean Spirit”: emphasizes that healing is wholeness and not merely cure. The demons of the Gospels are linked to the fears of today, fears that often manifest when people with disabilities appear in social settings. #265 “O Christ, the Healer”: this hymn provides an opportunity to ask what healing is, and contains the conclusion that “wholeness is our deepest need.” #332 “Spirit of Faith, Come Down”: with the phrase “give us eyes to see / who did for every sinner die,” Wesley, as is often the case, extends both need of healing and offer of grace to all. Instead of using blindness as a metaphor for the lack of spiritual vision, he refers to taking away a veil from our sight. #351 “Pass Me Not, O Gentle Savior” (Frances Jane “Fanny” Crosby Van Alstyne): Crosby’s (1820-1915) hymns should play an important role in any consideration of a Disability Awareness service. She wrote poetry, secular songs, and magazine articles, as well as hymns. Crosby’s eyesight was permanently damaged during infancy by improper medical treatment. Thereafter, she was educated at the New York Institute for the Blind, which had recently started operations. Upon graduation, she stayed as a teacher, where she was active in efforts to establish similar schools nationwide, and thus continued her groundbreaking work by making presentations before Congress. In 1864, she became claimed conversion at a Methodist service. She then sensed a call to hymn-writing. It’s believed that she wrote about 8000 hymns—her main publisher, Biglow and Main, purchased 5959 from her. This hymn, with images from Luke 18.35ff, seems to be autobiographical, expressing hope for a miraculous cure, doubts when there is none, and resolution to trust and seek only Christ. Relief and comfort are found not in a cure, but in Christ’s presence, which is a worthwhile view of healing. Also see #369 “Blessed Assurance” and #419 “I am Thine, O Lord” #363 “And Can It Be that I Should Gain” (Charles Wesley): The fourth stanza, “Long my imprisoned spirit lay / fast bound in sin and nature’s night / thine eye diffused a quickening ray / I woke, the dungeon flamed with light; / my chains fell off, / my heart was free . . .” is worth including because it uses a strikingly different metaphor for lack of spiritual sight than many other hymns. #369 “Blessed Assurance”: Most of Crosby’s hymns are very personal, which is typical of the time when she wrote. They also reflect testimony, and gain new understanding when approached as the work of a person who was expanding the roles allowed for people with disabilities (and for women). “Blessed Assurance” (369) claims divine inspiration, showing that the Spirit is available to women, and to people with disabilities, as well as to men. This form also is responsible for much of the “me” language that can also be problematic, so the balance of community must be sought. Also see #419 “I am Thine, O Lord.” #370 “Victory in Jesus”: There are two problems with this hymn. First, it focuses on the “old” story, which separates it from today. Second, it relates that after hearing about Jesus causing the “lame to walk again and . . . the blind to see,” there is a response of “come and heal my broken spirit.” The equation of cure and healing is not helpful in dealing with disabling conditions. #378 “Amazing Grace”: Although popular far beyond religious circles, two of the images in this hymn are problematic, and receive regular discussions in theological journals. First, the “amazing” part of grace is that it came to a “wretch,” a person traditionally considered outside the boundaries of divine love. It bears repeating that Wesleyan theology teaches the availability of grace to all. Second, the line “I once was lost, but now am found / was blind, but now I see” equates human blindness with sin. This is often exacerbated when the hymn is sung to other tunes, such as the “Gilligan’s Island” theme, with repetition of this line. We suggest an amendment to the last line of “I slept, but now I wake,” which is in line with metaphors used during the time of the New Testament. #419 “I am Thine, O Lord”: Although Crosby was a Methodist, hymns such as “I am Thine, O Lord” veer close to Calvinist theology where grace is only offered to the elect. They also, in the tradition of the time, offer salvation and include instructions to newcomers (e.g., an hour kneeling in prayer). However, it also portrays a longing for heaven, which is where the present joy will be complete, which is more Wesleyan. Bodily images are of being drawn or led down a path (which one would expect of a blind person) who has “heard” the divine call. It is typical of Crosby to include references to sight. Her blindness was not total; she could discern dark and light, and large objects. Thus her soul can “look up” with “hope” of better vision some day. #425-450, 5he section “Social Holiness”: these hymns counter much of the hyper-individualism that pervades culture in general, and as such, are a reminder that churches are communities, and that being a complete body of Christ implies the inclusion of everyone, whatever their mental or physical capabilities. The section also counters the escapism of much Romantic hymnody. #505 “When Our Confidence is Shaken”: Green’s hymns are modern, and draw on modern (if no longer contemporary) idioms, however, they still speak to current concerns. In this hymn, the lines “when the spirit in its sickness seeks but cannot find a cure / God is active in the tensions of a faith not yet mature” speak to the limited finite understanding of the infinite, and reassure us that in our lack, we are still accepted, and that we do not need to have final answers to every question. #507 "Through It All" #560 “Help Us Accept Each Other”: This hymn needs to move, not drag (as is often the case) and presents a useful reflection on mutual acceptance, hinting at the forgiving as we are forgiven petition of the Lord’s Prayer. #562 “Jesus, Lord, We Look to Thee” #581 “Lord, Whose Love Through Humble Service”: This hymn mentions healing as a compassionate act, although a word emphasizing the distinction of healing and freedom from cure is again worthwhile. #592 “When the Church of Jesus” # 593 “Here I Am, Lord” # 605 “Wash, O God, Our Sons and Daughters" #666 “Shalom to You” The Faith We Sing #2032 “My Life Is in You, Lord” #2051 “I Was There to Hear Your Borning Cry” #2052 “The Lone, Wild Bird” #2095 “Star-Child” #2128 “Come and Find the Quiet Center” #2175 “Together We Serve” #2181 “We Need a Faith” #2184 “Sent Out in Jesus' Name” #2211 “Faith Is Patience in the Night” #2223 “They’ll Know We Are Christians by Our Love” #2224 “Make Us One” #2225 “Who Is My Mother, Who Is My Brother” #2228 “Sacred the Body” #2237 “As a Fire is Meant for Burning” #2238 “In the Midst of New Dimensions” #2243 “We All Are One in Mission” #2249 “God Claims You” Compiled by Tim Vermande, webservant, Lynn Swedberg, disability consultant, with assistance from members of the UMAMD (Jackson Day, Evy McDonald, Eric Pridmore, Deb Wade, Robert Walker, Nancy Webb), and other members of the United Methodist Committee on DisAbility Ministries from various sources. 10/2013