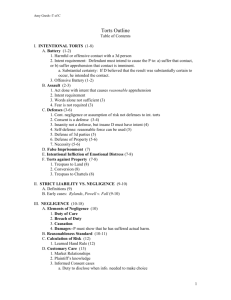

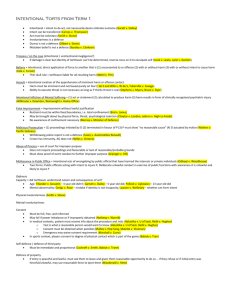

Torts-delisle-20102

advertisement