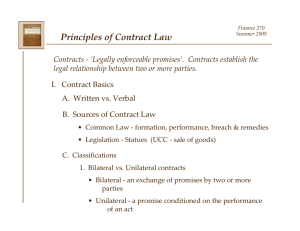

I. Formation - Penn APALSA

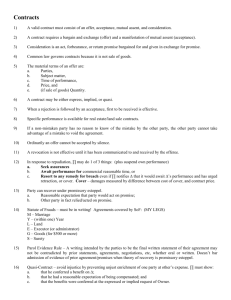

advertisement