acusación dyncorp - Agencia Prensa Rural

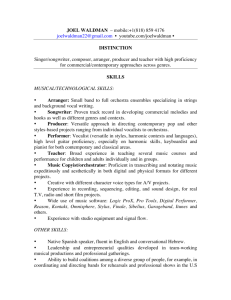

advertisement