Making a Modern Literature in Banyuwangi, East Java

advertisement

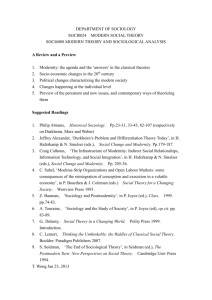

TRADITION AND THE MODERN WORKSHOP ONE: 28-30 MAY 2003 “MODERNISM, HISTORY, THOUGHT: VISIONS OF SOCIAL INTERCHANGE” Project Leaders: Professor Christopher Shackle FBA (South Asia and Religions, SOAS) Professor Tim Mathews (French, UCL) Research Assistant: Dr Ross Forman Venue: Foster Court 114, UCL ABSTRACTS Ben Arps (Cultures of South East Asia and Oceania, Leiden) Making a Modern Literature in Banyuwangi, East Java The idea that a nation has a language has a literature, which seems to originate from 18th-century German philosophers like Herder, has become part of the ideology of language the world over. Indonesia and Banyuwangi – the region with about 1.5 million inhabitants that forms the far eastern tip of the island of Java – are no exceptions. The modern language that local cultural activists want Osing (formerly regarded as a dialect of Javanese) to become, and that they actively strive to make it, has a genealogy; it is not a dialect but a language, it has its own distinctive vocabulary, spelling, grammar, and phonology, it is taught in schools, and it has, needless to say, its own literature, both classical and a modern. Unfortunately, the last-mentioned attribute of a proper language is not without its problems in the case of Osing. The classical literature consists in ancient narrative poems and traditional songs. As to the former, the titles of a tiny handful of works are known, but the texts themselves have been lost in Banyuwangi and, although manuscripts exist elsewhere, their study has not been taken up. The latter is a corpus of orally transmitted songs performed during annual trance rituals in a number of villages and also part of the repertoire of a traditional festive song-and-dance genre that remains popular in the countryside. These songs are subjected to a distinctly modern mode of interpretation, namely as patriotic texts describing the struggle against the Dutch oppressors. The modern literature consists almost exclusively of free-verse lyrical poems that are published in whatever medium is available – and that is not much. The local insert of a national newspaper, anthologies published if funding can be found, and periodicals published, usually in a few issues only, under the same circumstances. Although the conditions for the creation of a modern Osing literature are thus not particularly favourable, dozens of authors do try. A Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 2 further important factor is that this modern literature exists, and intersects with, a thriving local pop music industry with lyrics in Osing. The paper, then, examines a case study, not of a modernist period or stream within a literature that is already modern, but of the very creation of a modern literature in the contemporary world. I analyse the attempts by a small but influential cultural elite to create a confidently modern literature as part of the modern language that is concurrently being discovered, described, and performed. Part of this phenomenon is also the fact that modern modes of interpretation are brought to bear on certain traditional texts. These efforts take place against a background of pervasive cultural traditionalism and orality in society at large, the lack of a writing tradition, and a thriving local radio- and recordings-based popular culture. The society in which these efforts are made is a multi-ethnic and multilingual one (speakers of Osing make up only a third to a half of Banyuwangi’s population, the remainder being the descendants of immigrants who settled here during the last century). Models are provided by two cultural and lingual juggernauts, Javanese (with 80 million speakers the largest “regional” language and culture of Indonesia, with a written literature going back at least 1200 years) and Indonesian, the national language and culture itself, which is the main vehicle for reading, writing, and publishing throughout the republic. Although the particulars are unique, many of the general circumstances are not restricted to contemporary Banyuwangi – in fact the current process of cultural change is part of a worldwide trend towards the formation and recognition of language- and discourse-based ethnic identities. In the course of the paper I will give some comparative attention to the position of literature in the modernization of marginal languages earlier in Indonesia and elsewhere in the world. Malcolm Bowie (Christ’s College, Cambridge) Art and Science in Proust’s Writing I will be examining the co-presence in Proust's great novel of art criticism on the one hand and an informal philosophy of science on the other. I will be asking what sort of fictional texture these two very different discourses together create, and what difference it makes to our reading of the work that the narrator who performs with such subtlety in both registers should, overall, be a model of unreliability. João Cezar de Castro Rocha (Letters, State University of Rio de Janeiro) On Not Traveling to Europe: Mario de Andrade's Voyage around His Country Latin American avant-garde artists traveled constantly as well as lived abroad for extended periods. It would not be absurd to suggest that as important as the Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 3 introduction of new artistic techniques and concerns in their home countries were, so were the innumerable travels undertaken by writers and artists such as Jorge Luis Borges, Tarsila do Amaral, Oswald de Andrade, Alejo Carpentier, Armando Reverón, among many others. Indeed, traveling seemed to be part of the artistic activity itself. Nonetheless, the Brazilian author Mário de Andrade, certainly one of the most well-read and therefore well-informed artists of his time, deliberately decided not to travel to Europe — the Mecca of the avant-garde in the 1920s. This was not an untroubled decision, once Brazilian artists followed the model of going to Paris for their Ph.D. degrees in avant-garde’s techniques and attitudes. In this lecture, I will be discussing Mário de Andrade’s particular travel around his own country, and mainly around his library. It will be my contention that his decision, more than merely a personal choice, enlightens the complex task of being both an artist and an intellectual in a peripheral country. A pride of place will be given to his 1925 book of literary criticism A escrava que não é Isaura, in which he presented an insightful account of the avant-garde movements. Frank Dikotter (History, SOAS) Things Modern: Material Culture and Everyday Life in China (1880-1950) How 'modern' was China before the communist conquest? The prevailing image is that of a desperately backward country struggling to enter the twentieth century despite an overwhelming majority of earth-bound peasants, the only exception being a few islands of 'civilisation' in the treaty ports. Historians, moreover, have generally interpreted 'modernisation' as 'Westernisation', focusing on a small number of foreign-dominated concessions: the International Settlement in Shanghai, for instance, is portrayed as a 'bridgehead' between two worlds, a 'modern West' and a 'traditional China'. A number of critical studies have further attempted to show that modernity was a very limited phenomenon even in the treaty ports: Lu Hanchao most recently has tried to go 'beyond the neon lights', as the title of his book proclaims, in order to reconstitute the everyday life of ordinary Shanghai people away from the Bund: modernity appears as a fringe phenomenon in a city dominated by tradition. This paper will highlight the sheer extent to which material culture and everyday life in China were transformed by modernity, from the bicycle and the bus to the kerosene lamp and the family photograph, in large capitals like Beijing or remote provincial cities like Lanzhou. Modernity was not a set of givens imposed by foreigners, but a repertoire of new opportunities, a kit of tools which could be flexibly appropriated in a variety of imaginative ways. The local, in this process of cultural bricolage, was transformed just as much as the global was inflected to Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 4 adjust to existing conditions: inculturation rather acculturation accounts for the broad cultural and material changes which marked republican China. The radio could transmit traditional opera to a much larger audience, while courtesans advertised their services in modern newspapers. Poor rickshaw pullers used medical syringes to inject new opiates fabricated thanks to the tools of modern chemistry, while homes in Shanghai's shantytown were erected with iron cans from Standard Oil. Modernity brought in its wake material transformations which were a product of and a constraint upon particular historical configurations. Rather than emphasise the culture of consumption and the surface meanings of goods – as if their materiality is a given – the social construction of the material character of the world which surrounds us should be examined, an approach which accepts the interdependent and mutual relationship between people and things. Culture, from this perspective, is the glue which enables relationships to be constructed between social beings and the material world: in the words of Paul GravesBrown, 'culture is the emergent property of the relationship between people and things'. Rasheed El-Enany (Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, Exeter) The Arabs and Europe: The Desire to Emulate If Orientalism, according to Edward Said, provided the conceptual framework, the intellectual justification for the appropriation of the Orient through colonialism, Occidentalism, if one may use this label to indicate Arab conceptualisation of the West, tells in my view a different story; one not of appropriation but of emulation. And if Orientalism was about the denigration, and the subjugation of the Other, much of Occidentalism has been about the idealisation of the Other, the quest for the soul of the Other, the desire to become the Other, or at least to become like the Other. In my paper I shall examine the ambivalence of the Arab attitude to Europe since the first encounter in modern times between the two, i.e. since Napoleon’s campaign on Egypt in 1798, an event which did not only mark the beginning of modern times for Egypt and the Arab East in general, but which also heralded the process of European colonisation of the Arab world. The Arab response to the invading Other was simultaneously one of fascination and hate; fascination with the way of life and systems of thought that produced the modernity of the Other, that different quality that gave him the power, almost the right to dominate them, and hate for that very domination. This ambivalence of attitude found expression in different forms at different times during the past two centuries. I shall try to look at salient points in the process mainly through the examination of literary, rather than polemical, texts. Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 5 Clare Finburgh (French, UCL) Tragedy and Postcolonial Modernism: Kateb Yacine and the Algerian War of Independence The theatre of the Algerian writer Kateb Yacine occupies a unique space at the interface between powerfully contrastive tragic and modernist dramaturgies, ontologies and political ideologies. Kateb considers his tragedies to be committed politically to decolonisation. The dramaturgist Bertolt Brecht insists that the lack of optimism in the tragic genre is incompatible with politically committed theatre, reproving tragedy for its submission to the doctrine of destiny. This paper discusses the aptness of the tragic genre to the theatre of anti-colonial engagement. It situates Kateb between the dominant metropolitan genres of classical tragedy and modernist Brechtian epic theatre, in order to demonstrate how he refashions these Western literary models. Kateb revisits the ancient tragic tradition in drama, to entrap Algeria within a closed circuit of fatality and failure. Ancestral suffering and failure become prophecies fulfilled by descendents. This constant, ritual repetition in memory of past events reduces the present to a static, synchronic space that precludes diachronic transformation into the future. But concurrently, Kateb modifies tragedy in such a way as to propose a tentative exit from tyranny and terror. He creates a tension between stagnation in the circulatory repetition of ancestral mythology, and revolution through the vectorisation of history. His historicisation and politicisation of tragedy relies heavily on the Brechtian conception of committed theatre. But the paper reveals how Kateb resists the insistent optimism of Brechtian epic theatre. For Kateb, knowledge of historical facts can serve to emancipate the subjugated, but this knowledge is not an absolute guarantee of redemption, for its status can regress into that of a falsifying narrative. Kateb resists total clarity in favour of a tragic view of knowledge as delusion. His tragedy encapsulates both myth and history, past and future, weakness and affirmation, bad faith and existential will, tradition and modernism. He does not attempt to simplify these complexities, contrasts and contradictions inherent in his tragedy. He exposes them all, juxtaposing their energies and illustrating how they all contribute towards the intricate process of Algeria’s recreation, as it struggles form the past to meet the future. Regenia Gagnier (English, Exeter) Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 6 Modernity and Individualism: When Progress and Decadence are Interchangeable Terms This paper begins with a Victorian premise, “All Progress is progress toward individualism"” (Herbert Spencer, Progress, 1857), and a modern one, “Progress and decadence are interchangeable terms” (Clive Bell, Civilisation, 1928). Individualism was progressive because increasing differentiation led to perfect fitness for purpose, whether in the division of labour, natural selection, racial differentiation, or stylistics. Progress was decadent because increasing individuation led to the disintegration of the whole. The paper considers the scope and limits of individualism as central to modern western culture. Key examples are from the 1890s to World War 2, and key models will include autonomy, independence, and Will, both biological and social. The author's expertise is transatlantic—Britain, North America, and Europe—but she welcomes comparative approaches to individualism. Rahilya Gheybullayeva (National Academy of Sciences, Azerbaijan) Context, Dominata, Modernization, or Literary Types in National Literature as a Consequence of Modernization: The Azerbaijani Literature of the Soviet Period Throughout history there have been various nations, languages and cultures whose paths either crossed (for instance, Islam caused the spread of Arabic culture and Socialist ideology created a new state – the Soviet Union – from disparate nations), diverged from each other (in the way that Slavic culture diverged into Russian, Ukranian, Belarussian, Polish and Czech national cultures, Turkic split into Turkish, Uzbek, Azeri, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Gaugaoz) or run parallel to each other without meeting (ancient civilizations like the Egyptians and the Aztecs). Each of these three relationships brings differing changes in terms of modernisation. During different historical periods cultures appear in different contexts and zones of influence and, accordingly, the dominant factors determine a new orientation and modes of cultural development. One of the aspects of the question of tradition and modernisation is the investigation of a range of literary types within one unified form – the national literature. There has been a problem dealing with it on a vertical, or diachronic, level and a horizontal, or synchronic, level. What kind of great historical cultural changes or less significant collateral influences have led to new features in the national literature, and have generated new forms which have updated the literary type? Common themes between literature and a modern interpretation of history over two millennia throws up some interesting material for research in Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 7 this respect. In this context, the Soviet period could be characterised as a historical and cultural type in the twentieth century. This paper will try to show, through the example of Azerbaijani literature, how these changes affect traditional canonical elements of the culture. This paper will focus on the Azerbaijani literature of the Soviet period. The basic principle on which Soviet society was formed was Marxist-Leninist ideology. The literary form of Socialist Realism was created on the same basis. These new trends have resulted not only in irreversible losses, which are inevitable in any new movement, but have also enriched the culture and literature in completely new directions from Jabbarly at the beginning of the 20th Century to Samedoglu at the end. In one respect, the literature of this period became a mirror for the changes in Azerbaijani society, and new elements have appeared through a new form of bilingualism; this time Russian became the second language of Azerbaijani literature. So Azerbaijani, as well as other national literatures of this period, has kept certain national features in what was proclaimed as one of the main principles of a new literary method; the content was national and the form was socialist. With the disintegration of the Soviet Union and its ideological system there began the formation of a new literary type in Azerbaijani literature. Through this process of modernisation, one can see traces of the past, including the recent Soviet past. Sabry Hafez (Near and Middle East, SOAS) Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Literature: A Reversal of a Trajectory Abstract not provided. Jeesoon Hong (Chinese Studies, Cambridge) Transcultural Production of Gendered Modernism in China: Ancient Melodies (1953) by Ling Shuhua (1900-1990) In China, the literary history of Republican modernism was marginalized until the 1980s, and the modernism of women writers has been almost ignored until now. Ling Shuhua was a modernist writer who consciously practiced modernist literary styles in her short stories. In particular, the modernist genealogy she pursued was mainly that of British female modernists such as Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield. From the literary circle in Beijing, often referred to as Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 8 “Xiandai pinglun pai” (Modern Criticism Group) by Chinese literary critics and dubbed “Chinese Bloomsbury” by Ling Shuhua, she acquired the epithet of “Katherine Mansfield in China.” In this paper, I will explore Ling Shuhua’s cross-cultural practices, based on the fact that Ling Shuhua’s life-long project was to be an intercultural mediator. To date, compared with the relationships between male modernists in the West and China, those between female modernists have attracted scant attention. My main interest lies in what differences were articulated when a woman became an intercultural mediator, in particular in relation to nationalism; whether a subjective position in cross-cultural exchanges was easily granted to a woman; if not, what the barriers were and how they functioned. Ling was also well known as a “Guixiu pai” (Gentlewomen’s Group) writer. With critical analysis of the problematics immanent in the social articulation, I employ the label as the means of specifying the female modernist’s cross-cultural practices. The Chinese gentlewoman’s cross-cultural practices highlight the mediation between domesticity and transgression and the ambiguous dialectics between gentlewomanly amateurism and the professionalism of a modern writer on an international as well as a domestic level. The publication of her autobiographical fiction Ancient Melodies in England and an exchange of letters with Virginia Woolf in the process of producing the book in the 1930s may mark the climax of Ling’s cross-cultural practices. I use previously undiscovered letters from Ling Shuhua to Virginia Woolf and other members of the Bloomsbury group to modify and expand the present understanding of her cross-cultural practices and also those of Bloomsbury. This historical research leads me to re-evaluate the role of Julian Bell—the eldest son of Vanessa Bell and nephew of Virginia Woolf, in the transcultural production of the book. The publication of Hong Ying’s novel K and the recent lawsuit against the book have brought the love affair between Ling Shuhua and Julian Bell to wider public knowledge. From this incident, I explore the contiguity between genteel femininity and stardom, which is based on one’s double image of public and private lives. Reading Ancient Melodies—a collection of autobiographical short stories, I raise questions about how her approach to the short story was different, or differently accepted, from the two representative views of this genre, which were predicated upon the nationalist claim of realist writers and the avant-garde aesthetics of male modernist writers in China. I also explore how Ling Shuhua, a practitioner of traditional Chinese painting, developed the short story in a gentlewomanly way, interweaving domesticity and aestheticism. She often depicts the boredom of a gentlewoman at home from the artistic vision of Chinese painting. The aesthetic explorations to incorporate the short story and visual arts which are Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 9 observed in western modernism are also undertaken by Ling Shuhua. In her short stories she also endeavours to develop the modernist narrative device of languid unfolding, reminiscent of Woolf and Katherine Mansfield. Finally, in my historical investigation of the transcultural production process of Ancient Melodies, I explore the tension between autobiography and the short story, focusing on how Ling Shuhua’s self-positioning as a member of the feminine Chinese literati with distinctive intellectual and artistic ability can be seen in relation to her dubious negotiations with the commercial public gaze pertinently directed at her female body and her private life. I compare the original short stories, which were published as fiction in China before they were included in the book, with the English versions in the book. Luce Irigaray The Time of Becoming Human An era of our history amounts to a realization of one aspect alone of our humanity. We relinquish our potential to such a partial fulfilment and we then aspire to destroy it to free ourselves and enter another era. Our era requires other strategies for various reasons: culture is becoming global, and we are confronted with other traditions; human productions, especially technologies, represent a danger for humanity and the space of its dwelling, the planet itself. How can we turn to the heart of ourselves and recover our evolution? Two ways seem possible: dealing with a culture of our energy which allows us to reach an autonomy and interiority of our own; caring about being in relation with other(s), with respect for our difference(s), beginning with sexual difference, the most basic and universal one. Overcoming the crisis with which our humanity is confronted could perhaps happen by creating bridges between Eastern and Western traditions? Doris Jedamski (International Institute for Asian Studies, Leiden) The Novel-Humming Ulama, “Ai lap joe”, and the Narration of a Nation: Malay Novels at the Brink of Indonesian Independence. On 17 December 1939, approximately forty publishers, authors, journalists, school teachers, and religious leaders (ulama) met in Medan, Sumatra, to discuss the pros and cons of the new media coming from the West: radio, film, and, especially, the genre of the novel. The meeting was the climax of a debate which had begun about two years earlier and which had since developed into a most Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 10 controversial discussion focussing in on the question, to what extent Islam could allow, tolerate or even utilise the new media, in particular, the popular novel. One can argue that this debate derived from the strong modernisation tendencies among parts of the Islamic community in colonial Indonesia. It also indicates, however, a new national consciousness that was spreading among the pribumi, the indigenous population, that increasingly defined not only the Dutch colonisers as the Other, but also the Chinese and Chinese Malay. The question of who was Indonesian, and who was to partake in the new nation, had become a crucial one. Literature had become to play a decisive role in this process of selfdefinition. In order to comprehend fully the meaning of the literary debate mentioned above, one will have to look at the literary market at the time and the special role that the Chinese Malay writers and publishers played whose predominant position the Islamic writers strove to take over. The Islamic Sumatran writers and publishers, many of them also nationalist activists, were determined to lay the foundation of the future national identity excluding all Chinese and so-called peranakan. Though divided by diverging political and social visions, both Chinese Malay Islamic Sumatrans were confronted with the same changes and problems in the colonial society caused by Western modernisation. This paper not only aims at depicting the openly exercised self-reflecting process of the Islamic Sumatran and the Chinese Malay writers in the face of modernity, but also touches upon the undercurrent of subliminal communication between the both groups. In this context literature had grown into a vital medium that defined what was modern in a positive sense and what was modern to be rejected. It drew demarcation lines as much as it breached them. It designed and corroborated images of both allies and enemies, always also encouraging border crossings. Literature helped envision the modern nation. Takis Kayalis (Modern Greek Literature, The Hellenic Open University) Mythical Methods of Modernist Criticism: Notes on T.S.Eliot's “Historical Sense” This paper focuses on T. S. Eliot's transhistorical views, particularly as exemplified in the concepts of “historical sense” and “mythical method”, and investigates the crucial role these notions, disengaged from their original framework and used rather as universal axioms, played in the shaping of Greek literary culture during the second half of the twentieth century. More specifically, the paper shows how George Seferis naturalized eliotic concepts in the mid-1940s -particularly in his essays on Makriyannis and Cavafy—in order to construct a strong and ostensibly “indigenous” tradition of the modern, one Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 11 which would thereafter pre-empt alternative interpretations of the interplay of poetry, history, and myth in the context of Greek culture. This paradigm will hopefully illuminate and trigger discussion on broader issues, such as the ways in which key modernist concepts and practices were ideologically transformed and assimilated in the European periphery after WW II to produce modernist "national" traditions and facilitate their lasting cultural hegemony. Susanne Kuechler (Anthropology, UCL) Rethinking the Surface of Things: Pacific Modernity and Its Relevance The paper will be divided into two parts. The first part will present a perspective on Pacific modernity by tracing, in fashion, architecture and art, the role of the surface of things. ‘Wrapping in images’ may have become an icon of Pacific style, yet the imagistic quality of the surface of things belies its material quality. It is argued, that the surface of things, which frequently has been discussed as a hybrid form of cultural articulation in the face of colonial encounter, is of telling significance in its own right. What may appear to us as trivial and fleeting expressions of a seriousness that resides elsewhere, is in fact a material translation of thought . Pacific modernity is analogical in that it utilises surfaces and the processes embedded in their material form to incite resemblances and imagined connections from which a sense of the present can be fashioned that is at once a place for dwelling and for resistance. The second part of the paper compares the Pacific surface with the post-modern condition in the West. Thinking through, with and in images is, as Barbara Stafford recently argued, no longer the prerequisite of pre-modern cultures, but has arrived on the stage of art, architecture and fashion. The paper will conclude with a critique of the notion of the image and examine the theoretical conditions that would allow us to understand the complex relation between knowledge, thought and visual media. David Lomas (Art History, Manchester/AHRB Centre for Studies of Surrealism and Its Legacies) Remedy or Poison? Medicine and Technology in Diego Rivera’s History of Cardiology (1943 - 44) Murals Writing of the ambiguity of the Greek word pharmakon, and the resultant impossibility of adequately translating it, Derrida states that: ‘As opposed to “drug” or even “medicine”, remedy says the transparent rationality of science, technique and therapeutic causality, thus excluding…any leaning toward magic virtues of a force whose effects are hard to master.’ Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 12 Hopes and fears about modern science and technology were prevalent in twentieth century culture and society. Surfacing explicitly in the political and philosophical discourse, they are refracted also in visual culture. Modern science and technology, which drive economic and social development, could be viewed as a panacea for social ills. On the other hand, there was the familiar dilemma: can the technology we created be controlled, or is it destined to control us? These issues assumed a distinctive form in Mexico after the Revolution where poverty and backwardness pointed to the urgent need to modernise, which inevitably meant entering into a Faustian pact with the industrialised West, while at the same time there was a desire to assert an independent nationhood through the reclamation of a pre-European Aztec past. My paper will take Diego Rivera’s History of Cardiology murals as the basis for a discussion of the representation of technology and modernity in his work. Consisting of two vertical panels 6 x 4 metres in scale painted in fresco on movable frames as decorations for the auditorium of the Instituto Nacional de Cardiologia in Mexico City, there is an underlying complementarity between Rivera’s murals which gather together an illustrious pantheon of forebears for the newly constellated specialism of cardiology and the emphatic modernity of the institute, built in a Bauhaus functionalist style, that houses them. While it is apparent that Rivera was working to a brief provided by Dr Ignacio Chavez, Director of the Institute, I will argue that the representation of history in the murals as a vertical ascent propelled by an impersonal dialectic of science and technology is inflected by Rivera’s dialectical materialism and the optimistic faith that he shared with other Marxists in the period in technology. My interest is in the pharmakon-like character of technology, in its potential as both a remedy and poison, and the rhetorical and visual strategies by which Rivera seeks to ensure that the ‘transparent rationality of science, technique and therapeutic causality’ shall predominate. A second aspect of the History of Cardiology murals related to the first concerns the status of indigenous medicine which Rivera depicts in four horizontally arrayed panels below the two vertical ones. The individual panels represent Chinese, Egyptian, African and Aztec medicine of the ‘pre-Christian’ era (in the context of Mexican history this would refer to the era before the Spanish Conquest). The inclusion of these four archaic civilisations can be understood in the light of an influential theory espoused by José Vasconcelos, a former Minister for Education who had done much to foster the nascent muralist movement. Reflecting a mood of widespread euphoria following the Revolution, Vasconcelos believed that a new universal era of Humanity was about to be born and that Mexico would be in its vanguard. Drawing upon the racialist theories of Gobineau, along with mystical philosophies, to give form to his messianic hopes, Vasconcelos claimed that a fifth race, the cosmic race of the future, would come about as a result of the fusion and synthesis of four races that had been Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 13 responsible for the major civilisations up until the present. As in the Detroit Industry murals where Rivera had depicted four races on each of the walls of the courtyard, the four panels in the History of Cardiology murals may evoke the archaic civilisations whose admixture was expected to engender the universal culture of the present. Like Vasconcelos, Rivera’s vision of modernity was one that stressed its abstract universalism - as does Chavez likewise in his insistence that science belongs to no single culture or race. The Mexican anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, in his book Mexico Profundo (1996), mounts an impassioned critique of what he saw as ‘a technocratic vision derived from foreign models’ and adopted as a national plan for modernisation by a Mexican minority ‘organised according to the norms, aspirations, and goals of Western society.’ This Westernisation plan he sees as going hand in hand with the subjugation and marginalisation of indigenous communities whose cultural roots lie in Mesoamerican civilisation. Rigidly separated from the vertical, dynamic ascent of History, and painted in grisaille (Rivera perhaps meant to recall archaic pre-Mexican wall painting), the portrayal of indigenous medicine here evokes a shadowy, subterranean world of mausoleums and the archaeological past – rather than a still living culture and set of alternative health practices. It is instructive to compare the subordinate relationship between indigenous and modern in this context with Rivera’s later mural at the Hospital de la Raza, entitled The History of Medicine in Mexico: The People’s Demand for Better Health (1953). Whereas the former can be seen as embodying the technocratic ideology of the medical profession, the latter it will be argued corresponds more closely to the viewpoint of their ethnically diverse patients. Timothy Mathews (French, UCL) Modernism: A Place of Decay Modernism plays out the tensions between a utopian and a tragic view of the world and of human perfectibility. For Steven Pinker in The Blank Slate, the lessons of evolutionary biology and the selfish gene have not and cannot be absorbed by the those that would rid society of aggression and suffering. Adam Phillips on the other hand, in Darwin’s Worms, reads Darwin with Freud rather than against him, and offers a knowledge based on remnants and transience, on the evolved as without purpose, on the future informed by the past but not dictated by it. In Literature, Art and the Pursuit of Decay, I have looked at decay from in European modernism from a textual perspective; and approached it not in thematic terms – people depicting decay in either pleasure or horror - but in formal terms - the pursuit of decay within the practices of art themselves. Form and the distaste for form co-exist rather than co-habit; unresolved tensions Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 14 emerge between the freedom of formal play and an ethical, ideological, psychoanalytical suspicion of all such play. Drawing especially on the visual, I shall be presenting examples of this art of formal decay, or decay as achievable through forms, of forms that aspire to their decay. Perhaps only tension rather than resolution can emerge in this conflict of form and the formed, innovation and transience, progress and suffering, orthodoxy and revolt. I will not be suggesting that forms speak only of form; but trying to follow the paths of form to their beyond; constructions we know to those we cannot imagine; identification and their empires to their transience. What dialogue might there be between this aesthetic and textual approach to European modernist utopia or tragedy, and approaches from other experiences, histories and methods? Laura Mulvey (Art, Film and Visual Media, Birkbeck) Passing Time: Reflections on Cinema from a New Technological Age Over the last twenty years, alongside the other significant changes that have taken place in the world, the cinema has been deeply affected by the development of electronic and digital moving image technology. Many theorists and cultural commentators have responded by pronouncing the cinema 'dead'. On the other hand, as I argue in this paper, new technologies can also be seen to have given new life to the old mechanical, celluloid based cinema of the past. Concentrating exclusively on this relationship, that is, from the present to the past, the paper does not discuss the relation of new technologies to the cinema today or in the futures. Rather, the argument reflects on: the cinema's close and historic relationship to modernity and the utopian teleology encapsulated in the concept of cinephilia. the impact of new technologies on aesthetic issues raised by avant-garde film and its uncertain relation to narrative. new ways of thinking about questions of time for which the cinema can function as 'time machine' and as metaphor. The paper is intended to draw attention to, without full discussion, the politics implicit in concepts such as 'the end of an era' and the ordering of history into periods. Francesca Orsini (Oriental Studies, Cambridge) The Trouble with Realism: Realism and its Others in the Twentieth-century Hindi Novel Recent scholarly work has examined the question of the “rise of the novel” in non-western countries (Mukherjee, Moretti), variously emphasising “foreign influences” or “local genealogies”. In this paper, I would like to tackle another thorny issue, that of realism in the novel, focusing on the work of admittedly the first and most accomplished master of realist fiction in Hindi and Urdu, Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 15 Premchand (1880-1936). In the first instance, I will consider the reactions of contemporary critics and reviewers who were rather taken aback by Premchand’s “realism”, i.e. his choice of contemporary social issues and of unexceptional characters. Critics mused about the legitimacy of literature “with a purpose” (can it be great Art?) and about the need to feature “proper Indian characters” and lofty sentiments. What do these reactions tell us about the aesthetic and generic expectations of the time? Conversely, once Premchand’s fame was established, his work, and especially his last novel, Godan (The Gift of a Cow, 1936) became the standard by which fictional realism came to be measured. As a consequence, his other works were often deemed “not realistic enough”, and the non-realistic features in them (in terms of melodramatic characterisation, supernatural elements, the role of chance, etc.) have been seen as “weaknesses” and “faults”. Here I am interested in seeing what kinds of strategies Premchand resorted to in these novels, and to what aim. I am guided in this by Christopher Prendergast’s book Balzac: Fiction and Melodrama (1978), where he argues that Balzac had recourse to melodramatic narrative strategies but fitted them into a personal conception of life and of social forces. Finally, in Hindi critical discourse after Premchand and after Independence, realism has become, not unusually I guess, a regular requirement for “good fiction” and a by-word for truth in fiction. Whereas for films the existence of a non-realistic code has been accepted, in fact accepted earlier by ordinary viewers than by critics and scholars, in the case of fiction value judgements are made along a scale which goes from “very realistic” to “very unrealistic”, with often little attempt at understanding the intentions and achievements of the work in question. This is particularly true when traditional narratives are considered: they may either be dismissed as “non realistic” or else revalued for their supposedly realistic descriptions of characters and places. In both cases, the original conventions, intentions and aesthetic values are overlooked. Realism, in other words, has become a disciplinary norm that is part of a package of modern critical axioms which contains also “literature and society” and “poetry as the expression of personal feelings”. In this sense, I would see my enquiry into realism and fiction as fitting within the workshop on “Modernism, History, Thought: Visions of Social Interchange”. Christopher Pinney (Anthropology, UCL) The Body and the Bomb: Technologies of Modernity in Colonial India B.G. Tilak and Bhagat Singh were among the leading advocates of violent opposition to British rule in India. Tilak might be seen as a neo-traditionalist when Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 16 contrasted with the atheistic Marxist-Leninist modernity of Bhagat Singh's Hindustan Socialist Republican Army. The substance of the paper focuses on the prosecution of Tilak in Bombay in 1908 following his advocacy in Kesari of modern and mobile technologies of bombmaking, and Bhagat Singh's celebrated mimicry of an English colonizer in order to avoid capture by the police at Lahore Railway station in 1931. Both incidents dramatize new, fluid and mobile, practices and identities. Finally, a set of contrasts are drawn between these two paradoxically similar figures and M. K. Gandhi who, through his own essentialist corporeal politics, appeared to perform a profound critique of modernity. George Sebastian Rousseau (Modern History, Oxford) The New Nostalgia Diagnosis of the Postmodern Karl Jaspers, a physician before he became an influential German philosopher, began his career by launching, in 1909 in Heidelberg, a (medical) nostalgia diagnosis within the stream of existing philosophical and scientific accounts of this human phenomenon. Jaspers' nostalgics fell dead from the press. I inquire, first, what the basis of Jaspers' nostalgics was, then explore its reception during the lead-up to the Great War and in the aftermath of that war, as well as its relation to other nostalgics, Freudian theories of memory and trauma, melancholy and mourning, and - most crucially - its larger relevance for twentieth-century notions of exile and homelessness. Christopher Shackle (South Asia and Religions, SOAS) Spiritual Heritage and Romantic Fantasy in a Modern Urdu Writer The broader context of the paper is that of the successive tensions between tradition and the modern in the reshaping of South Asian Islam as seen its literary expressions from the colonial period in the mid-nineteenth century onwards, while the specific focus is on the several collections of Urdu short stories published in the 1980s and 1990s by Mazhar ul Islam, who is regarded as one of the leading exponents of the modernist style amongst contemporary Pakistani prose writers. The tensions which animate Mazhar ul Islam’s varied oeuvre are examined from two perspectives. One is culture-specific, asking how a late twentieth-century Pakistani writer handles the challenge of the modern through a mixture of selfconsciously modernist techniques and a selective reappropriation of tradition in the form of the local Sufi poetry of the pre-modern period. The other is more Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 17 free-ranging, suggesting that Mazhar ul Islam’s carefully developed authorial persona with its elaborately constructed foundation in a fantastic romanticism is not only to be seen as an individual instance of the association to be posited cross-culturally between the modern and the tragic but also as a reiteration of profoundly embedded pre-modern cultural understandings of the relationship between literature and human experience. Tsering Shakya (South Asia, SOAS) Is Tibetan Culture Congruent with Modernity?: Tradition Versus Modernity: The Debate in Tibet Nothing is improved by changing except the sole of your shoe. (A Traditional Tibetan Proverb) All that is old is proclaimed as the work of gods, All that is new is thought to have been conjured by the devil, Wonders are thought to be bad omens This is the tradition of the land of Dharma. (Gedun Chonphel, 1904-1952) The thousand brilliant accomplishments of the past cannot serve today's purpose, yesterday's salty water cannot quench today's thirsts, the withered body of history is lifeless without the soul of today, the pulse of progress will not beat, (Dhondup Gyal, 1958-985) Since the 1980s, a fierce debate has been conducted in the forum of Tibetan literary magazines. The debate has focused on the nature of Tibetan tradition and its inability to change. The critics of tradition allege that Tibetan culture is deficient and lacks the means to modernise. They see modernisation as means of emancipation from the shackles of the past. Although the debate has been conducted in the form of the modern versus the traditional, at the heart of the debate is a concern with Tibetan self and alterity I would argue that modernism becomes a metaphor for freedom and emancipation for the present situation of the Tibetan as a colonised subject. The modernist posits that freedom is only possible by embracing modernisation and discarding the past, thus enabling the creation of a new Tibetan self. For others, the location of Tibetan self can only be found in tradition and the incursion of modernism erodes Tibetan self. Anna Snaith (English, Anglia Polytechnic) Colonial Modernism: Una Marson in London Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 18 This paper begins with an image: a photo of the contributors to George Orwell’s BBC radio poetry programme Voice in 1942. Una Marson’s central position in the photo, alongside T. S. Eliot, William Empson and Mulk Raj Anand among others, is the starting point for my discussion of her place in modernist London and how this serves to complicate versions of literary modernism in which the colonial presence is an abstract trace. Una Marson, a black Jamaican poet, dramatist, broadcaster, journalist and political activist and her experiences in and representations of London in the 1930s and 40s, speaks to the oft- overlooked impact of colonialism and colonial writers on metropolitan modernism. The transformative exchanges which took place between colonial and metropolitan writers and the anti-imperial versions of modernity precipitated by the voyage in suggest the need for a discussion of modernism and empire which moves beyond primitivist aesthetics. I will explore what London meant for Marson, by focusing on her work as secretary to Sir Nana Ofori Atta Omanhene in 1934 (head of a delegation from the Gold Coast to the Colonial Office) and Haile Selassie during his exile in 1936, and her work as Head of the BBC’s West Indies Service (and founder of its ‘Caribbean Voices’). I will place her play London Calling and selected poems in the context of this work, to argue that her pan-Africanism, her cultural nationalism, her anti-imperialism and her feminism were both facilitated by and yet developed in response to her experiences in London. As a black woman writing in pre-WWII London, her work provides a rare perspective on the contiguities of race, gender and nationality in the heart of empire. Martin Swales (German, UCL) Goethe's 'Faust': History and Modernity Goethe's Faust is a work that seeks to understand the secular, indivdualist, scientific temper of the modern age; and it does so through a complex intertextual debate with a fable that enshrines (of all tings) the value-scheme of Christian didacticism. Time and again Goethe's reckoning with modernity (paper money, genetic engineering, technology) is also a reckoning with versions of the historical past (Classical Greece, the Middle Ages). Moreover, the form of his great drama embodies, in generic terms, the transitional and transgressive energies of modern culture as the text moves back and forth between morality play, theatrum mundi, allegorical drama, social realism, philosophical drama, visionary theatre, pots-modern extravaganza. Tania Tribe (Art and Archaeology, SOAS) Form and Utopia: Imaging Modernity in Africa and Latin America Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 19 Modernity has been defined by Habermas as the secularizing intellectual project which began to take shape during the eighteenth century as the result of an intense effort to implement rational modes of thought based on objective science and universal morality and law. Its aims were to release humanity from the arbitrary use of power and to establish universal, eternal and immutable human qualities – equality, freedom, faith in human intelligence and universal reason, with the arts and sciences achieving control of natural forces, moral improvement and happiness for all. The essentially utopian nature of the modernity project has, nevertheless, been consistently exposed and denied. Assuming the fleeting and the fragmentary as the necessary pre-condition for the fulfilment of its promises and requiring the destruction of old social and economic patterns, it has carried the seeds of its own contradictions. The death camps of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia have shattered the optimism of modernizing forces, re-focusing the human will to violence and placing severe limitations on the powers of rational knowledge, thus begging the question of whether such a project is ultimately possible. The wide range of specific local responses to the values of the modernity project throughout the world adds to the complexities of its analysis. The radical break with local histories and traditions, which stems from exposure to modernity’s search for scientific domination of nature and the overthrow of irrational myth and religion, has forged new forms of political and social structuring, re-situating human beings in new, unique ways within their own cultures. Power is a clear component in this process. Edward Said’s Orientalist model argues that the Western notion of Orientalism has resulted from a Nietzschean process, as a political doctrine willed over the Orient because the Orient was weaker than the West, and which has entirely ignored the Orient’s difference. Cultures and nations located in the East, however, continues Said, possess “a brute reality” which lies beyond anything that could be said about them in the West. Said’s domain of otherness deals with a “real” or actual Orient which he perceives as untouched by Western categories and in possession of a concrete radical non- or counter-identity, of an entirely particular nature. Clearly, this model applies to other areas of the world besides the Orient, and one must consider not an unchanging modernization process but rather the diverse ways in which the radical shift towards modernity and modernization has taken place, as well as the many forms in which the Enlightenment project has often met its downfall. This paper examines the specific paths taken by this process as it has unfolded in two radically different societies in Africa and Latin America – Ethiopia and Brazil, looking at the ways the local conceptual and experiential reality has modified the modernity model developed by Western authors like Habermas. In the case of Brazil, modernity really begins at the end of the nineteenth century, Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 20 with the establishment of a liberal republic based on positivistic values and intent on fostering large-scale technological and industrial development. Ethiopia, however, has had to plunge directly from a feudal universe into one where technology only began to be introduced very selectively, directly by the last absolute emperor, Haile Selassie, before it embarked on the Derg’s utopian Marxist experiment. The paper questions the relationship between capitalism, identity and modernity in these two specific regions, taking into consideration local forms of thought and values. It assesses the role of the cities and urban environments in the establishment of local forms of modernity, looking also at the ways its values have been embodied in painting, sculpture and architecture. Finally, the paper reflects on the significance of the shift towards the “postindustrial” and the “postcapitalist” in areas where capitalism has either taken root in very different ways from those of the European and North American experience, or not taken root properly at all. It asks whether the postmodern reliance on feeling and experience above rationality, science and politics might not ultimately be the only possible means to anchor human life, experience and understanding amid the fragmentation and chaos resulting from modernity’s demise. Emma Wilson (French, Cambridge) Oblivion, the City and the Senses: Hiroshima mon amour Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour (1959) has received new attention in recent work on trauma and history. Cathy Caruth explores a seeing and a listening in the film ‘from the site of trauma’. This paper will explore the specificity of that site as urban space, as post-traumatic metropolitan stage. Urban encounters and contact with the city – key sensory triggers within modernity – become a means to apprehending, or failing to apprehend, catastrophe. Movement through the city, steps traced and trajectories followed, write and rewrite a narrative of commemoration that is also, in Hiroshima mon amour, a failed quest for knowledge. Encounters with and in the city are figured as a means to approach and embrace the other, to open the self to the other (to an other location, to a site of trauma, to cultural difference). Yet the fear remains that in this rebuilt urban space, the self may only glimpse her own reflection in the glassy surfaces of the city façades. Resnais’s film likewise asserts its own failure to apprehend Hiroshima, reimagining the city as it does within the (Western) frame of film noir. Offering a reading of Resnais which privileges spaces and locations, the material and the sensory, this paper will explore the ways in which his work approaches trauma and oblivion through questions of rebuilding and reconstruction. In thinking forgetting, Hiroshima mon amour explores the pain and failure of attempts to correlate the city as site of trauma with the city as rebuilt space. Tradition and the Modern Workshop One Abstracts 21 Drawing on work in urban theory, on Andreas Huyssen’s discussions of memory and forgetting in Twilight Memories and Zizek’s Welcome to the Desert of the Real, this paper will gesture towards some of the limitations of knowledge, memory and commemoration. Henry Zhao (East Asia. SOAS) "Buddhist Modernity" as Seen in Recent Chinese Art and Literature Abstract not provided.