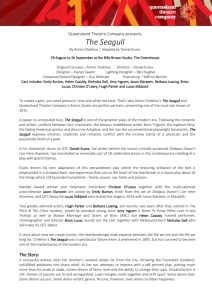

Creation of the Seagull

advertisement

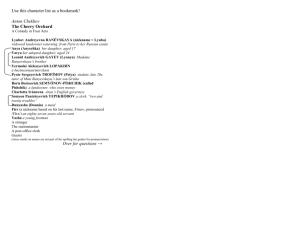

Creation 1895 of the Seagull After making a lot of promises that he would never deal with theatre again, after a good many one-act plays performed all over Russia, Chekhov started to write a new drama on the 21st of October, 1895. "I am writing with pleasure, although I offend against the laws of theatre. Comedy, three female and six male roles, four acts, a landscape (a panorama of the lake), many discussions about literature, little action, five pounds of love." On the 18th of November he wrote: "I finished the play. I started forte and finished pianissimo, breaking all the rules of theatre art. It turned to be a short novel." (...) Chekhov read the play in front of a wide company, this was the first audience of the Seagull, and the theatre critics mainly used to the overwhelming plots of Sardou and Dumas generally didn't like it. The first objection was that Potapenko the seducer of Lika was easily discernible in the figure of the famous writer, Trigorin. (Chekhov has condensed many autobiographical elements in this character, too, but the critics didn't notice it at the beginning.) The censorship was studying deeply and for a long time the text of the Seagull. The main condition was that the young heroine should not notice the affair of her mother and Trigorin. They had a detailed correspondence about this problem, dealing with even the deleting or substitution of certain conjunctions. Chekhov lost his polite patience to the end of the summer and instead of detailed texts he started giving short instructions to Potapenko who was discussing with the censors in the name of Chekhov. Furthermore - that has never happened before to the author scrupulously correcting even the fifth edition of his own works - he wrote to Potapenko: "You can substitute the sentences 'I cannot make out what she is up to. She simply doesn't speak.' with 'You know, I don't like her' or whatever you want, you can even quote from the Talmud. Or just insert something like that: 'Oh, in her age! Oh, oh, isn't she ashamed!" Ágnes Európa Gereben: Csehov Publishing világa House, (The world Budapest, of Chekhov) 1980 1896 - the premiere of the Seagull in the Alexandrinsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg There were only a few rehearsals before the performance. Nobody understood the play except Comissarjevskaya, one of the most prominent personalities of Russian theatrical art, who played Nina, and received the text four days (!) before the premiere. The actors haven't memorised their roles... On the evening of 17th October 1896, before the premiere, the chaos reached the summit. Everybody was perplexed, the general atmosphere was anything, but not cheerful. The audience (attracted to theatre by the bonus play of Saint Petersburg's favourite comedienne) was waiting patiently at the beginning. But when the famous monologue of the insert play has started: "Men, lions, eagles and doves, red deer, geese, spiders, and you, mute fish living in the water" - the enthusiastic words of Comissarjevskaya were interrupted by some silly guffaw. As if given the cue, the entire audience started to whistle, laugh, hiss and beat with the feet. The voice of the actress was hardly even heard in the general pandemonium... The performance turned out to be a scandal; even experienced old men of literature as Suvorin agreed in never ever having seen such a horror. The author has disappeared in the meantime. After the performance they were desperately looking for him, but he was nowhere. He left with the first freight car to Melihovo. When his sister arrived home, instead of greeting her, he said her not even mention the play. His diary has preserved only a few sentences with the date of 17th October: My play, the Seagull was presented today at the Alexandrinsky Theatre. It was not successful. (...) The critics never spoiled Chekhov. Still, what he had to bear at 17th October and the days after was incomparable to everything before. Here is one typical example out of the many, written by an otherwise important literary critic: "I don't know, I don't remember when Mr. Chekhov turned to be a great talent, but for me it is undoubtedly true that it was a mistake to raise him to this literary rank... His play entitled Seagull gives first of all the impression of a writer's awkwardness, of the literary inertia of a frog blowing up itself. One feels that the author is willing to say something what exactly, he himself doesn't know - but is incapable of reaching his goal. And all the efforts, all the strains of this tiny little art seem to be pathologically piteous..." Dozens of papers published critics written in this manner. (...) There was only one critic who was astonished by this attitude: "Whom and in what ways could Chekhov hurt, whom could he insult, who is he hindering to deserve this malevolence? Is it possible that skills and popularity are sufficient reasons to evoke it?" The second performance - the improved variant of the play, presented for a different audience, with roles that finally were memorised- was met with the well-deserved success. Comissarjevskaya could send the happy telegram in the first minutes after the performance: "Anton Pavlovich, my darling, we won!" The success came too late, this time the performance attracted no attention, and the play was removed from the agenda after the fifth show. Chekhov wrote in December to Suvorin: "Lately I have calmed down, my mood is just the usual, but I cannot forget what happened - as I couldn't have forgotten a slap for example..." Ágnes Gereben: Csehov Európa Publishing House, Budapest, 1980 világa (The world of Chekhov) Mizinova to Chekhov, Pochrovskoye, 1st November 1896 (...) It is scandalous that you write three line-letters - this is egoism and disgusting laziness! As if you didn't know that I am collecting your letters in order to sell them later and thus assure a living for my old days! Let me know when you arrive to Moscow. We need to discuss a particular problem; I won't keep you long. Don't fear to stay at my place. I will not allow myself any indecency, if only because I'm afraid to ascertain about happiness never coming. Thus I will have at least a little hope left. Good bye. (Ar.)* too times rejected by you, that is L. Mizinova See, now you have a pretext to call me liar! Here everybody says that you have borrowed the Seagull from my life, and they also say that you're upbraiding someone else here, too! *Ariadna, see Chekhov's short story with the same title Csehov szerelmei (Chekhov's loves), ed. by Annamária Radnai, Magvető Publishing House, Budapest, 2002 "The Seagull is a big rubbish, it does not worth anything; it is written as if Ibsen wrote it." Tolstoy Note in Suvorin's diary, 11th February, 1897 1898 - the second staging of the Seagull at the Art Theatre, Moscow, directed by Stanislavsky Arkagina Trepliov Nina Trigorin Masha - Olga - - Knipper Maria (the - later Vsevolod Constantin Lilina wife of (Stanislavsky's Chekhov) Meierhold Roxanova Stanislavsky wife) The Seagull has failed for the first time at the premiere. Many were trying to find its reasons. The cast in the Alexander Theatre was really impressive, even the great actress of the period, Comissarjevskaya played a role. And it wasn't only the premiere to fail, the further performances failed, too. Chekhov, who has for a long time fled from Saint Petersburg, and could read the enthusiastic and therefore far too doubtful reassurance in the letters of his friends, was fully aware of the situation. Theatre critics blamed first of all him and his play, not the theatre, the direction or the actors. Most of the critics considered that the play has failed because it was a weak drama. It is impossible to find out from contemporary critics what the real reason of the failure was, the single document that can offer some clues is the director Evtihy Karpov's much later found notebook. It seems that he has misunderstood the play. According to his notes, Karpov's interpretation - and thus also his presentation - was focussing onto the melodrama of Nina Zarechnaya. It states that "The heart-broken Nina stands lonely and she is proudly facing all the other characters, these egoistic, petty-minded people." (Role-interpretation is a question to doubt, knowing that the actress has received Nina's role four days before the performance.) Two years later Nemirovich-Danchenko fell in love with the play and persuaded Stanislavsky to make the performance. At that moment Stanislavsky neither has liked, nor has understood the play. It was summer, he withdrew to his brother's estate and wrote the director's text variant of the Seagull, thus performing the reform of Russian theatre. He started to love and understand the play while writing about it. The director's text variant was first published in 1938, forty years after the premiere (later on, in 1981it was re-published in six volumes, together with other director's text variants). In the introduction Stanislavsky considered it important to distance himself in a certain degree from his own earlier work, as his ideas have changed a lot in the meantime. This was the method of a despot, with whom he was on bad terms at the moment, as he stated; however, three decades after the Seagull he wrote in the same manner the director's variant for Othello (this was published in 1945). For his excuse it should be mentioned that Stanislavsky was cured in Nizza and he directed the rehearsals from there, that's why such a precise director's variant was needed. Stanislavsky called the carefully written director's text variant a score, the visible and audible music of the play. Everything happening on stage was in there. However, one thing was missing, it could not have been integrated: if the performance played according to these instructions was going to be successful. It was successful. Stanislavsky was not proclaiming the ideas of a new theatre creation at the time of "writing" the Seagull, he was not predicting the reforms yet, but he made it, wrote it, directed it (and also played it). The innovations could really be noticed in this copy. The date of the premiere was 17th December 1898. A part of the innovations have become routines since then, they have been used up. The instructions for the scenery, sounds, noises, movements and actors demonstrate the idea that this theatre should be based on being and life, not on a playing-game. It is the creation of a second realism. It is realism itself. Since then this realism stays in theatre as some kind of illness (or virtue?). (...) One focus point of Stanislavsky's reform was the space, the scenery, and the stage-picture. He wanted to liquidate the empty stage, the proscenium. He wanted to create a life-like space (see: a second reality), which was packed, with a lot of things in a disorder, both in the first two acts (happening "outdoors") and the last two ("the house"). (...) Stanislavsky built up consequently and in an ostentatious manner a fourth wall out of mainly those things that were in the foreground of the stage. He sat his actors onto a long bench as a fourth wall, facing with the back the audience. That's how they were watching Trepliov's play. (Stanislavsky succeeded in building this fourth wall so dominantly that since then everybody constantly wants to demolish it, together with the other three.) (...) Olga Leonardovna Knipper (who became Chekhov's wife in 1901) played the role of Arkagina. She wrote that the Seagull's important factors were was neither the scenery, nor the costumes, but only the actors. Meierhold played Trepliov. Later on, when Meierhold left the Art Theatre (and he became an opponent of it), he wrote that the success of the Seagull was due to the actors' performance, not to the direction of Stanislavsky. Knipper and Meierhold played very well. Chekhov also liked them. Chekhov wanted to take the role of Nina from Roxanova. The actress has left the theatre soon. Masha, performed by Maria Lilina (Stanislavsky's later wife), was much better than she was. All the critics considered it important to mention Masha. According to the critics the other weak interpretation of the play was Trigorin, performed by Stanislavsky. Not the director, but the actor was unsatisfying. (...) Chekhov has altered in the greatest degree Medvedienko's role. He was very much afraid of Medvedienko's character; he deleted all the earlier texts, until in the last variant Medvedienko was almost not talking at all (but he was present). Chekhov must have feared that this Medvedienko constantly talking about money can easily slide into a caricature-figure. (...) "What kind of person is this writer?"- Sorin raised the question in Act I. What kind of person was Trigorin, then? Stanislavsky was not a good Trigorin. Chekhov didn't like it himself. His figure was built on one single feature: weakness. He was a weakling, an extremely complacent Trigorin- wrote Ephros about him. Stanislavsky played the role of Trigorin for seven years; he transformed the role in 1905. Andrea Tompa: Száz éve és ma (A hundred years ago and today). Színház, 2002/2 1890-1892 Lika Mizinova Chekhov and Mizinova met in the autumn of 1889, when Lika became a teacher of the Rjevsky Gymnasium, where the writer's sister, Maria Chekhova was working. Lika really impressed Chekhov already when first visiting his family. Contemporary notes mention them as inseparable; they went together to concerts, exhibitions, and meetings. Mizinova made notes about Sahalin for Chekhov; she helped him in preparations. When taking farewell, Chekhov gave a photograph to Mizinova, writing on the backside the following: "For the ever nicest person who I flee from to Sahalin, and who has clawed my nose. I solicit the suitors and admirers to wear a nose-pad. Chekhov. P.S. this note as well as our postcards does not commit me for anything." The atmosphere of the note is similar to the mood the correspondence of Chekhov and Mizinova in the first years radiates. The letters from 1891-1892 prove the existence of a close, intimate friendship. But when it came to enthusiasm for each other (the first letters demonstrate a liking and a wish for being liked), they seemed to have different behaviours. Chekhov didn't even react to Lika's undefined or sometimes defined sentiments. The motive of hopelessness appeared in Lika's letters in the autumn of 1892, when she realised that she could not force Chekhov to put his cards on the table. "Oh, please come, and save me!" - she desperately wrote to him. Chekhov didn't answer but he wrote to Suvorin: "I don't want to marry and I don't have anybody to marry. Damn it! I would be bored by the problems of a wife. Of course it wouldn't be bad to fall in love. It is boring to live without love." Shortly afterwards the adventure with Chekhov turned publicly into a different affair, the romance of Lika and Ignaty Potapenko. The new love seemed to make disappear the previous, defining, strongest sentiments. Although the correspondence and relation of Chekhov and Lika lasted for many years, they have parted for ever. Lika's life got harder and harder. She gave birth to Potapenko's child in 1894, who left her not much later and returned to his wife. Lika experienced again a tragedy when her daughter died in pneumonia in 1896. Lika was lost, her unshaped talent could not develop in any direction. Her ambitions in the domains of teaching, singing, acting, translating and fashion design all ended in a fiasco. Their letters in the following years were friendly and colloquial. At the end of the 1890's Olga Knipper has appeared in Chekhov's life. In this period the correspondence between Lika and Chekhov almost came to an end. In 1901 Lika applied for a place to the workshop of the Art Theatre, but she was accepted only as an extra. She became an extra in the place where Knipper was the heroine. In 1902 she married Alexander Akimovich Sanin, the actor and director of the Art Theatre and soon they moved abroad. After the Great October Revolution the returned for a short while, but afterwards they settled for good in Paris. Lika came never back again to Russia. Radnai Annamária: Introduction Csehov szerelmei (Chekhov's loves), ed. by Annamária Radnai, Magvető Publishing House, Budapest, 2002 Lidia Avilova At one time with the Mizinova-affair lasting for years, Chekhov developed a less problematic but nevertheless affectionate relationship with Avilova, the delicate young writer from Saint Petersburg. They also have met in 1889; she was also a Lidia and she was not less charming than Mizinova. She always met Chekhov when visiting the capital, they were regularly writing to each other. This relationship was never as developed as with Mizinova; it was no source of a "danger" as the girlish Avilova was a mother with three children. However, she would have followed Chekhov without a moment's hesitation if he had asked her. In the winter of 1895, when Czehov had allegedly confessed: "I was in love with you", Avilova offered to go with him. Namely she sent a small medallion in secret - she thought that it was also an incognito - to the writer and engraved onto it: "Novels and short stories by A. Chekhov, page 267, line 6 and 7." In the indicated place it says: "If you ever need my life, come and take it." The addressee realised whom the present came from, but he was not far the person to overturn the life of a family. Neither were his feelings strong enough for taking such a step. But he has used the idea afterwards: the Seagull's Nina Zarechnaya confesses her love in this way. Ágnes Gereben: Csehov Európa Publishing House, Budapest, 1980 világa (The world of Chekhov)