The Creole Origins of African American Vernacular English:

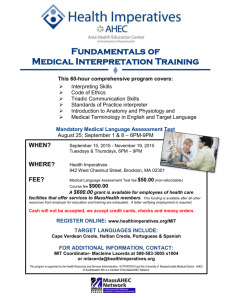

advertisement