Name: Period _____ Date ______ McGlaughlin RENAISSANCE

advertisement

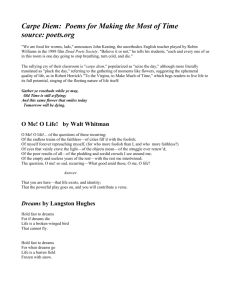

Name: _______________________________________ Period _____ Date _____________ McGlaughlin RENAISSANCE POETRY PACKET Andrew Marvell (1621–1678) During his lifetime, Andrew Marvell was known for his political activities rather than his poetry. After receiving a degree from Cambridge University, he traveled abroad for several years before returning to England in 1650 to tutor the daughter of the Parliamentary general Lord Fairfax. Three years later, Marvell became tutor to Oliver Cromwell’s ward, William Dutton. Marvell showed an extraordinary adaptability in a turbulent time. Although he was the son of a Puritan minister and frowned on the abuses of the monarchy, he enjoyed close friendships with supporters of Charles I in the king’s dispute with Parliament. He also opposed the government of Oliver Cromwell, leader of the Puritan rebellion and then ruler of England. In 1657 he became an assistant to John Milton, the Latin secretary for the Parliamentary government, and in 1659 was himself elected to membership in Parliament, an office he held until his death. After the Restoration, he seems to have been influential in securing Milton’s deliverance from prison and from possible execution. Marvell’s poetry was not published until after his death, and his true talent as a poet was not fully recognized until the 20th century. Had we but world enough, and time, This coyness, lady, were no crime. We would sit down, and think which way coyness (n) shyness; aloofness, often as part of a flirtation To walk, and pass our long love’s day. 5 Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side Ganges: a great river of northern India Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide Of Humber would complain. I would Love you ten years before the Flood, And you should if you please refuse 10 Till the conversion of the Jews. My vegetable love should grow Page 1 of 9 Humber: a river of northern England, flowing through Marvell’s hometown Vaster than empires, and more slow; An hundred years should go to praise Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze; 15 Two hundred to adore each breast, But thirty thousand to the rest; An age at least to every part, And the last age should show your heart. For, lady, you deserve this state, 20 state: dignity Nor would I love at lower rate. But at my back I always hear Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near: And yonder all before us lie Deserts of vast eternity. 25 Thy beauty shall no more be found, Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound My echoing songs; then worms shall try That long-preserved virginity, And your quaint honor turn to dust, 30 And into ashes all my lust: The grave’s a fine and private place, But none I think do there embrace. Now therefore, while the youthful hue Sits on thy skin like morning dew, 35 And while thy willing soul transpires At every pore with instant fires, Now let us sport us while we may, And now, like amorous birds of prey, amorous (adj) full of love or desire Rather at once our time devour 40 Than languish in his slow-chapped power. Let us roll all our strength, and all Our sweetness, up into one ball, And tear our pleasures with rough strife Thorough the iron gates of life: 45 Thus, though we cannot make our sun Stand still, yet we will make him run. Page 2 of 9 languish (v) to become weak; droop Robert Herrick (1591–1674) As a young man, Robert Herrick tried his hand at goldsmithing, the family trade, before attending Cambridge University when he was twenty-two. There he earned two degrees and, a few years later, was ordained as a priest. Herrick was an active member of London society. He loved the city and was disappointed when assigned to a rural church in Devonshire. Here, he performed his churchly duties and wrote religious verse and musical love poems. Although not politically active, Herrick was evicted from his parish by the Puritans and allowed back only with the Restoration of Charles II. While barred from his church, Herrick returned to his native and beloved London, where he published some of his poetry in 1648. Unfortunately, because of the civil war, society was not very interested in Herrick’s light, playful verse, and his work was not much appreciated until the 19th century. Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old time is still a-flying; And this same flower that smiles today Tomorrow will be dying. 5 The glorious lamp of heaven, the sun, The higher he’s a-getting, The sooner will his race be run, And nearer he’s to setting. That age is best which is the first, 10 When youth and blood are warmer; But being spent, the worse, and worst Times still succeed the former. Then be not coy, but use your time, And, while ye may, go marry; 15 For, having lost but once your prime, You may forever tarry. Page 3 of 9 Critical Reading 1. Respond: If you were the lady, how would you respond to the speaker? Why? _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ 2. (a) Recall: Name three things the speaker and his mistress would do and the time each would take if time were not an issue. _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ (b) Connect: How do these images relate to the charge the speaker makes against his lady in lines 1–2? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 3. (a) Infer: Why would the speaker be willing to spend so much time waiting for his mistress? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ (b) Interpret: How does this willingness take the sting out of his complaint? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Page 4 of 9 4. (a) Analyze: What future does the speaker foresee for himself and his love in lines 25–30? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ (b) Connect: How do the images in lines 21–30 answer the images in the first part of the poem? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 5. Draw Conclusions: Why does the speaker save the urgent requests in lines 33–46 for the end? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Page 5 of 9 Critical Reading 1. Respond: How did you respond to Herrick’s images? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 2. (a) Recall: What advice does the speaker give women in lines 1–4? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ (b) Interpret: What does the advice mean? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ (c) Analyze: How do the images he uses convey the idea of passing time? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Page 6 of 9 3. (a) Interpret: What does the poem suggest about passing time? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ b) Connect: How does the last stanza answer these concerns? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 4. Hypothesize: What response could an opponent offer Herrick? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Page 7 of 9 “To His Coy Mistress” by Andrew Marvell “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” by Robert Herrick Read the following passage. Pay special attention to the underlined words. Then, read it again, and complete the activities in the sidebar. Charles I was born in 1600, the second son of James I and Anne of Denmark. In his childhood he was a sickly and stammering child, but in his prime he was an excellent horseman and a strong-willed king. Upon becoming king of England in 1625, Charles I immediately found himself in great trouble – his father had left the kingdom with vast financial and political problems. Charles’s own marriage to the French Roman Catholic princess Henrietta Maria alarmed Protestant England. At first, Charles was cold to his wife. For example, he would not let her French servants tarry forever in England but sent them home. Later, however, he grew close to his queen. Echoing the French fashions that pleased her, he spent huge sums on the arts and his court, causing further concern among his people. Charles faced a Parliament hostile to his concept of absolute rule – a subject he was never mute about – and King and Parliament quarreled on numerous occasions. Tired of the ongoing strife, Charles dissolved Parliament three times and ruled eleven years without it. In 1642, Charles’s financial and political troubles led to a civil war pitting English King against English Parliament. In 1647, Charles was taken prisoner by the forces of Parliament. Tried for treason and found guilty, he was beheaded on January 30, 1649 and buried in a vault beneath Windsor Castle. A week after Charles’s death, the office of king was abolished. For some, the lack of an English monarch was a unique disaster. A true royalist believes that the soul of a nation lives in its king, and that this soul transpires from his body with his last breath; the nation’s soul can only find a home in the new monarch. For Charles’s opponents, however, the soul of the nation was in its people. For them, the end of English monarchy was an astonishing opportunity for democracy. Page 8 of 9 1. Circle the phrase that means something opposite to “in his prime.” In a complete sentence, explain whether you are in your prime. _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ 2. Underline the synonym for vast. Name something else that is vast. _______________________ 3. Underline the phrase that shows that the servants did not tarry. What does tarry mean? 4. Circle the words that tell what Charles spent huge sums echoing. 5. Circle the words that tell what Charles was never mute about. 6. Underline the word that is a clue to the meaning of strife. 7. Underline the word that indicates the location of a vault. What would a vault look like inside? _______________________ 8. Circle the word that is a clue to the meaning of transpires. “To His Coy Mistress” by Andrew Marvell “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” by Robert Herrick Literary Analysis: Carpe Diem Theme Examples of the theme of carpe diem, which is Latin for “seize the day,” can be found throughout world literature. Robert Herrick’s poem “To the Virgins” contains lines that are frequently cited as an example of this theme. Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old time is still a-flying; And this same flower that smiles today Tomorrow will be dying. The metaphor of the rosebuds is a particularly appropriate symbol for the carpe diem theme. The rose is one of the most beautiful of flowers, yet it lives only a short time. DIRECTIONS: Answer the following questions in complete sentences. 1. In the opening lines of “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time,” Herrick uses the image of rosebuds as a symbol of the carpe diem theme. What other things does he use as a symbol? _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ 2. In the opening lines from “To His Coy Mistress,” the speaker implies that coyness is a crime. How does the speaker use the carpe diem theme to justify this implication? Had we but world enough, and time, This coyness lady were no crime. _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ 3. What other lines from “To His Coy Mistress” reinforce the carpe diem theme? Give one example. _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ 4. In “To His Coy Mistress,” what is the speaker’s purpose in trying to convince his listener that life is short? Use an example from the poem to support your statement. _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ Page 9 of 9